Kolkhoz facts for kids

A kolkhoz (Russian: колхо́з) was a special kind of collective farm in the Soviet Union. Imagine a big farm where many families worked together, and the land and tools were shared. Kolkhozes were one of two main types of farms in the Soviet Union, the other being state farms called sovkhoz.

These collective farms started appearing after the October Revolution in 1917. The idea was to move away from old ways of farming, where poor farmers worked for rich landlords, and also from individual family farms. At first, joining these farms was supposed to be a choice. But starting in 1928, the government made it mandatory for farmers to join, a process called forced collectivization.

Contents

What Does "Kolkhoz" Mean?

The word "kolkhoz" is a short form of the Russian words "kollektívnoye khozyáystvo," which means "collective farm." It's like taking parts of two words to make a new, shorter one.

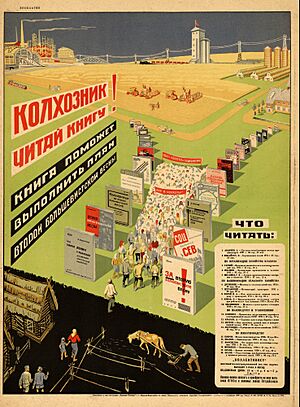

People who worked on a kolkhoz were called "kolkhoznik" (for a man) or "kolkhoznitsa" (for a woman).

How Kolkhozes Were Organized

A kolkhoz was officially set up as a "production cooperative." This means it was supposed to be a group of farmers who joined together to produce food. The rules said that kolkhozes should be managed by the members themselves, with everyone having a say.

However, in reality, after the forced collectivization, kolkhozes didn't work much like true cooperatives. Farmers were often forced to join and couldn't easily leave. If they did leave, they couldn't take their share of the farm's property. The land itself was owned by the Soviet government, not the farmers.

The government also had a lot of control over the kolkhozes. They told the farms what to grow and even chose who would manage them. Over time, the difference between kolkhozes and state-owned sovkhozes became very small. By the late 1960s, kolkhoz members even started getting a guaranteed wage, just like workers on state farms. This showed that they were more like employees than independent cooperative members.

How Work Was Structured

Work Groups: Brigades

To manage the work on large kolkhozes, workers were divided into groups called brigades. These brigades usually had 15 to 30 families. A brigade would be responsible for a specific area of land, its equipment, and animals. A leader called a brigadir was in charge of each brigade.

Smaller Teams: Zvenos

Sometimes, brigades were split into even smaller teams called zvenos (which means "links"). These smaller teams would handle specific tasks.

Life on a Kolkhoz During Stalin's Time

On a kolkhoz, workers were supposed to get a share of the farm's products and profits based on how many days they worked. But often, kolkhozes didn't pay their members in cash at all. In 1946, many kolkhozes paid no cash, and some paid very little grain.

The government also made kolkhozes sell their crops at very low, fixed prices. The government then sold these products to consumers at much higher prices. This big difference in price was a major way the Soviet government made money. This money was used to buy machinery from other countries and to help the Soviet Union become an industrial power. Leaders like Stalin believed this was important to make the country strong and avoid military problems.

For example, in 1948, the government paid kolkhozes about 8 rubles for 100 kilograms of rye, but then charged wholesalers 335 rubles for the same amount. These low prices didn't change much for many years, meaning the farms often got less than the cost of growing the food.

Kolkhoz members were allowed to have a small piece of private land, usually about 1 acre (0.4 hectares), and some animals. Even though these plots were tiny, they were very productive. In 1937, these small private plots produced over 21% of all agricultural output, even though they made up less than 4% of the total farmed land.

Kolkhoz members also had to work a minimum number of "labor days" each year, both on the kolkhoz and for other government projects like building roads. If they didn't complete enough labor days, they could lose their private plot or even face legal trouble. However, most workers completed far more than the minimum required labor days.

The government set specific "labor day" values for different tasks. For example, thinning a small area of sugar beets might be worth two and a half labor days. But often, it took much longer than 8 hours of actual work to complete a "labor day" task. This system was more about the government controlling costs and production than fairly paying workers for their time.

Kolkhozes After 1991

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union in December 1991, the country began to change from a government-controlled economy to a market economy. The number of kolkhozes and sovkhozes quickly went down after 1992. Many of them changed their names or became different types of farms.

Even though their names changed, many of these new farms still worked a lot like the old kolkhozes. The way they were managed and how people worked didn't change much at first.

In some former Soviet countries, like Armenia, Georgia (country), and Azerbaijan, kolkhozes mostly disappeared, and individual family farms became more common. In Central Asian countries like Turkmenistan and Tajikistan, kolkhozes were officially changed into "peasant associations" or other types of farms.

In Belarus, kolkhozes continued to exist, though their official names changed. The government still owns most of the land and supports farming a lot, similar to how it was in the Soviet Union.

See also

In Spanish: Koljós para niños

In Spanish: Koljós para niños

- Collective farming – Learn about similar types of farms in other countries.

- Kibbutz – A type of collective community in Israel.

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |