Revolutions of 1848 facts for kids

| Part of the Age of Revolution | |

Barricade on the rue Soufflot, an 1848 painting by Horace Vernet. The Panthéon is shown in the background.

|

|

| Date | 12 January 1848 – 4 October 1849 (1 year, 8 months, 3 weeks and 1 day) |

|---|---|

| Location | Western, Northern, and Central Europe |

| Also known as | Springtime of Nations, Springtime of the Peoples, Year of Revolution |

| Participants | People of Ireland, France, German Confederation, Hungary, Italian states, Denmark, Moldavia, Wallachia, Poland, and others |

| Outcome | See Events by country or region

|

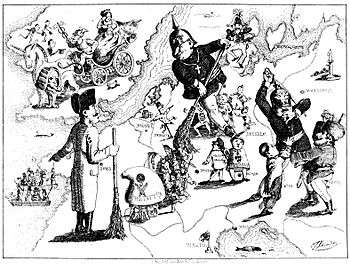

The Revolutions of 1848 were a huge wave of changes that swept across Europe. They are also known as the Springtime of Nations or the Springtime of the Peoples. These revolutions happened over more than a year, from 1848 to 1849. It was the biggest series of uprisings in European history.

These revolutions were mostly about getting more democracy and freedom. People wanted to get rid of old systems where kings had all the power. They also wanted to create independent nation-states, where people who shared a language and culture could have their own country. The first revolution started in Italy in January 1848. Soon, over 50 countries were affected!

However, the revolutionaries didn't work together much. Many things caused these uprisings. People were unhappy with their leaders and wanted more say in government. They demanded freedom of the press and other rights. Working-class people wanted better economic conditions. Also, a strong feeling of nationalism grew, where people wanted to unite based on their shared identity. A big problem was the European potato failure, which caused widespread hunger and unrest.

The uprisings were led by groups of reformers, middle-class people, and workers. But these groups often didn't stay united for long. Many revolutions were quickly stopped, leading to thousands of deaths and many people being forced to leave their homes. Still, some important changes lasted. For example, serfdom (a system where peasants were tied to the land) ended in Austria and Hungary. Denmark stopped having an absolute monarchy (where the king had total power). The Netherlands introduced representative democracy, where people elect their leaders. The most important revolutions happened in France, the Netherlands, Italy, the Austrian Empire, and the German states. The wave of uprisings ended in October 1849.

| Top - 0-9 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z |

Why the Revolutions Started

It's hard to point to just one reason why the 1848 revolutions happened. Many changes were happening in Europe during the first half of the 1800s. People wanted more freedom and a say in how they were governed.

New technologies were changing how working-class people lived. Newspapers became more common, spreading political ideas. New ways of thinking, like liberalism (more freedom for individuals), nationalism (people with shared culture should have their own nation), and socialism (more power for workers), became popular.

Some historians say that bad harvests, especially in 1846, caused a lot of hardship for farmers and poor city workers. Many nobles were also unhappy with kings who had too much power. For example, in 1846, Polish nobles in Austria rebelled.

The middle class and working class both wanted changes. They agreed on many goals. But the middle class often started the revolts, while the working class provided the main force. The uprisings usually began in cities.

City Workers' Lives

Many people moved from the countryside to cities in France, causing cities to become very crowded. Many middle-class people were afraid of the poor workers. Unskilled workers often worked 12 to 15 hours a day, living in dirty, unhealthy slums. Traditional craftspeople felt threatened by new factories and machines.

New trade laws and factories made the gap bigger between master craftspeople and their helpers. In Germany, the number of helpers grew by 93% between 1815 and 1848. Poor city workers saw their buying power drop after 1825. For example, people in Belgium, France, and Germany ate less meat after 1830.

A financial crisis in 1847 caused many people to lose their jobs. In Vienna, 10,000 factory workers lost their jobs. In Hamburg, 128 businesses went bankrupt in 1847. Countries hit hardest by this economic problem were often the ones that had revolutions in 1848.

The situation was similar in the German states. Factories started to appear in parts of Prussia. Cheap, machine-made clothes in the 1840s hurt German tailors who made clothes by hand. City workers had to spend half their money on food, mostly bread and potatoes. When harvests failed, food prices went up, and demand for manufactured goods went down. This led to more unemployment.

During the revolution, workshops were set up for unemployed men to do construction work. Women also got workshops. Workers sometimes destroyed machines because they felt the machines gave employers too much power over them.

Life in Rural Areas

More people in rural areas meant less food and land for everyone. Many people moved within Europe or to places like America. Farmers' unhappiness grew in the 1840s. They started taking back common land that they had lost. The number of people caught stealing wood in one German area jumped from 100,000 in 1829–30 to 185,000 in 1846–47.

In 1845 and 1846, a potato blight (a plant disease) caused a food crisis in Northern Europe. This led to people raiding potato storages in Silesia in 1847. The blight hit Ireland the hardest, causing the Great Irish Famine. But it also caused hunger in Scotland and across Europe. Rye harvests in Germany were only 20% of normal, and the Czech potato harvest was cut in half. Food prices soared; the cost of wheat more than doubled in France and Italy.

There were 400 food riots in France from 1846 to 1847. German protests about social and economic issues increased from 28 in the 1830s to 103 in the 1840s. Farmers were upset about losing shared lands, rules about forests, and old feudal systems. These systems forced peasants in places like the Habsburg lands to work for nobles.

Nobles' wealth and power came from owning farmland and controlling peasants. Peasant anger exploded in 1848. But their goals were often different from city revolutionaries.

Powerful New Ideas

Even though powerful leaders tried to stop them, new ideas became very popular. These included democracy, liberalism, nationalism, and socialism. People demanded a constitution (a set of rules for government), the right for all men to vote, press freedom, and other democratic rights. They wanted citizen armies, freedom for peasants, and an end to trade barriers. They also wanted to replace monarchies with republics or at least limit the power of princes with constitutional monarchies.

In the 1840s, 'democracy' meant that all men, not just property owners, should be able to vote. 'Liberalism' meant that governments should rule with the consent of the governed (people's agreement). It also meant limiting the power of the church and state, having a republican government, and protecting freedom of the press and individual freedoms.

'Nationalism' was the idea that people who shared a language, culture, religion, or history should be united in their own country. This idea became very appealing before 1848. For example, František Palacký's 1836 History of the Czech Nation highlighted conflicts with Germans. Patriotic song groups were popular in Germany, singing about national pride.

'Socialism' in the 1840s didn't have one clear meaning. But it generally meant giving more power to workers and having a system where workers owned the means of production (like factories).

These ideas—democracy, liberalism, nationalism, and socialism—were often grouped under the term radicalism.

What Happened During the Revolutions

Spring 1848: Big Successes

In spring 1848, the world was amazed. Revolutions popped up everywhere and seemed to be winning! People who had been sent away by old governments rushed home to join the moment.

In France, the king was overthrown again, and a republic was created. In many German and Italian states, and in Austria, old leaders had to agree to liberal constitutions. Italy and Germany seemed to be quickly forming unified nations. Austria even gave Hungarians and Czechs more freedom and national status.

Summer 1848: Revolutionaries Split

In France, terrible street fights broke out between middle-class reformers and working-class radicals. In Germany, reformers argued a lot and couldn't agree on their goals.

Autumn 1848: Old Powers Fight Back

At first, the nobles and their allies were surprised. But then, they started planning how to get their power back.

1849–1851: Revolutions Crushed

The revolutions faced many defeats in summer 1849. The old powers returned to control, and many revolutionary leaders had to flee their countries. However, some social changes did last. Years later, nationalists in Germany, Italy, and Hungary achieved their goals of creating unified nations.

Events in Different Countries

Italian States

The first revolution of 1848 in Italy began in Palermo, Sicily, in January. People had rebelled against the Bourbon rulers before. This time, they created an independent state that lasted only 16 months before the Bourbons returned. But the constitution they made was very advanced for its time, aiming for a united Italian group of states. This failure was later fixed 12 years later when Italy became unified.

In February 1848, Leopold II of Tuscany, a cousin of the Austrian Emperor, granted a constitution. Other leaders, like Charles Albert of Sardinia and Pope Pius IX, followed. But only King Charles Albert kept his constitution after the uprisings ended. Revolts broke out in the Kingdom of Lombardy–Venetia, like the Five Days of Milan, which started the First Italian War of Independence.

The Republic of San Marco declared independence from the Austrian Empire. It joined the Kingdom of Sardinia to try and unite northern Italy against foreign rule. But Sardinia lost the war, and Austrian forces took back the Republic of San Marco in August 1849.

In Modena, Duke Francis V tried to stop the revolt with his army. But when volunteers came to help the rebels, he left the city, promising a constitution. A temporary government was set up. In the Papal States, a revolt forced Pope Pius IX out of his worldly power, leading to the Roman Republic.

France

The "February Revolution" in France started because people were not allowed to hold political meetings. This revolution was driven by strong feelings of nationalism and republicanism among the French people. They believed that people should rule themselves.

This revolution ended the rule of King Louis-Philippe and created the French Second Republic. After a short time, Louis-Napoleon, Napoleon Bonaparte's nephew, was elected president. In 1851, he took control in a coup and became a powerful emperor of the Second French Empire.

German States

The "March Revolution" in the German states happened in the south and west. There were large public gatherings and big protests. Educated students and thinkers led these movements. They demanded German national unity, freedom of the press, and freedom of assembly.

The uprisings were not well organized. But they all shared the goal of rejecting the old, powerful political systems in the 39 independent states of the German Confederation. The middle-class and working-class parts of the revolution split apart. In the end, the conservative nobles defeated the revolution. Many liberal leaders had to leave Germany.

Denmark

Denmark had been ruled by an absolute monarchy since the 1600s. King Christian VIII, a moderate reformer, died in January 1848. At this time, farmers and liberals were increasingly unhappy. Demands for a constitutional monarchy, led by the National Liberals, ended with a big march to the royal palace on March 21.

The new king, Frederick VII, agreed to the liberals' demands. He set up a new government that included important National Liberal leaders. The national-liberal movement wanted to end absolute rule but keep a strong, central government. The king accepted a new constitution and agreed to share power with a two-house parliament. It's said that the king's first words after giving up his absolute power were, "that was nice, now I can sleep in the mornings." Unlike other parts of Europe, this new system was not overturned by those who wanted to go back to the old ways.

Schleswig

The Duchy of Schleswig was a part of the Danish monarchy, but it was a separate duchy. It had both Danes and Germans living there. Germans in Schleswig were inspired by Pan-Germanism (the idea of uniting all Germans). They rebelled against a new Danish policy that would have fully joined the duchy with Denmark.

The German people in Schleswig and Holstein revolted. The German states sent an army to help them. But Danish victories in 1849 led to peace treaties. These treaties confirmed the Danish king's power but stopped Schleswig from fully joining Denmark. This rule was broken later, leading to another war in 1863 and a Prussian victory in 1864.

Habsburg Monarchy (Austrian Empire)

From March 1848 to July 1849, the Habsburg Austrian Empire faced many revolutionary movements. These often had a strong nationalist feeling. The empire, ruled from Vienna, included many different groups: German-speaking Austrians, Hungarians, Czechs, Poles, Croats, Ukrainians, Romanians, Slovaks, Slovenes, Serbs, and Italians. All of them tried to gain more freedom, independence, or even control over other groups during the revolution. The situation was even more complex because the German states were also moving towards greater German unity.

Hungary

The Hungarian Revolution of 1848 was the longest in Europe. It was finally crushed in August 1849 by Austrian and Russian armies. However, it had a big impact by freeing the serfs. It began on March 15, 1848, when Hungarian patriots held large protests in Pest and Buda (now Budapest). They forced the imperial governor to accept their 12 demands. These demands included freedom of the press, an independent Hungarian government, a National Guard, equal rights for all citizens, trial by jury, a national bank, a Hungarian army, and the removal of Austrian troops.

That morning, the demands were read aloud with poetry by Sándor Petőfi, which included the lines: "We swear by the God of the Hungarians. We swear, we shall be slaves no more." Lajos Kossuth and other liberal nobles asked the Habsburg court for a representative government and civil liberties. These events led to the resignation of Klemens von Metternich, the Austrian chancellor.

Emperor Ferdinand agreed to the demands on March 18. Hungary would remain part of the monarchy, but it would have its own constitutional government. The Hungarian parliament then passed laws that created equality before the law, a legislature, a hereditary constitutional monarchy, and ended restrictions on land use.

The revolution turned into a war for independence from the Habsburg monarchy. The new government, led by Lajos Kossuth, was at first successful against the Habsburg forces. Although Hungary united for its freedom, some minority groups within Hungary, like the Serbs and Romanians, supported the Habsburg Emperor and fought against the Hungarian Revolutionary Army.

After a year and a half of fighting, the revolution was crushed when Russian Tsar Nicholas I sent over 300,000 troops into Hungary. As a result, Hungary was put under strict military rule. Leading rebels like Kossuth fled or were executed. In the long run, the resistance after the revolution, along with Austria's defeat in the 1866 Austro-Prussian War, led to the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867. This created the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Galicia

The main center of the Ukrainian national movement was in Galicia. On April 19, 1848, a group of representatives, mostly Greek Catholic clergy, sent a petition to the Austrian Emperor. They asked that in areas of Galicia where Ukrainians were the majority, the Ukrainian language should be taught in schools and used for official announcements. They also wanted local officials to understand Ukrainian and for Ukrainian clergy to have equal rights.

On May 2, 1848, the Supreme Ruthenian Council was formed. This council aimed to divide Galicia into Western (Polish) and Eastern (Ukrainian) parts within the Habsburg Empire. They wanted to form a separate region with its own political self-governance.

Sweden

On March 18–19, a series of riots called the March Unrest happened in Stockholm, the capital of Sweden. Demands for political reform were spread around the city. A barricade was built and then stormed by the military. In the end, 18 to 30 people were killed.

Switzerland

Switzerland was already a group of republics, but it also had internal conflict. Seven Catholic regions tried to form a separate alliance called the Sonderbund in 1845. This led to a short civil war in November 1847, where about 100 people died. The Sonderbund was defeated by the Protestant regions, which had more people. A new constitution in 1848 ended the almost complete independence of the regions, turning Switzerland into a federal state.

Greater Poland

Polish people started a military uprising against the Prussians in the Grand Duchy of Posen (part of Poland). This area had been part of Prussia since 1815. The Poles tried to create a Polish political area, but they refused to work with Germans and Jews. The Germans decided they were better off with things as they were, so they helped the Prussian government regain control. In the long run, the uprising made both Poles and Germans feel more nationalistic and gave Jews equal rights.

Romanian Principalities

A Romanian liberal and nationalist uprising began in June in the region of Wallachia. Its goals were self-rule, ending serfdom, and allowing people to decide their own future. It was linked to the failed 1848 revolt in Moldavia. It aimed to overturn the old system set up by Russian authorities and end the special privileges of nobles.

Led by young thinkers and officers, the movement succeeded in overthrowing the ruling prince. They replaced him with a temporary government and passed many liberal reforms. Despite quick gains, the new government had conflicts between radical and more conservative groups, especially about land reform. Two failed attempts to overthrow the new government weakened it. Its international status was always challenged by Russia. After getting some support from Ottoman leaders, the revolution was finally stopped by Russian diplomats. In September 1848, Russia invaded and put down the revolution. Later, the rebels returned and achieved their goals.

Belgium

Belgium did not have major unrest in 1848. It had already gone through a liberal reform after the Revolution of 1830. Because of this, its constitutional system and monarchy survived.

Some small local riots did break out in the industrial areas of Liège and Hainaut. The biggest threat came from Belgian groups living in France. In 1830, the Belgian Revolution had been inspired by events in France. So, Belgian authorities feared a similar "copycat" event in 1848. Soon after the French revolution, Belgian workers in Paris were encouraged to return home to overthrow the monarchy and create a republic. Belgian authorities even expelled Karl Marx from Brussels in early March, accusing him of helping arm Belgian revolutionaries.

About 6,000 armed Belgians, called the "Belgian Legion," tried to cross the border. One group traveling by train was stopped and disarmed. The second group crossed on March 29 and headed for Brussels. Belgian troops stopped them and defeated them. A few smaller groups got into Belgium, but the strong border troops succeeded. The defeat ended the revolutionary threat to Belgium. The situation in Belgium improved that summer after a good harvest, and new elections brought a strong majority to the ruling party.

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

A common idea in the 1848 revolutions was that the liberal monarchies set up in the 1830s were too unfair or corrupt. People felt these governments didn't listen to the urgent needs of the people. They needed big democratic changes or, if that failed, to break away and build a new democratic state. This is what happened in Ireland between 1801 and 1848.

Ireland had been a separate kingdom but was joined with the United Kingdom in 1801. Most of its people were Catholic farmers. But power was held by Protestant landowners loyal to the UK. From the 1810s, a movement led by Daniel O'Connell tried to get equal political rights for Catholics within the British system. They succeeded in 1829. But like in other European states, a radical group criticized the liberals for being too slow.

In Ireland, a nationalist and republican movement, inspired by the French Revolution, had existed since the 1790s. This grew into a movement for social, cultural, and political reform in the 1830s. In 1839, it became a political group called Young Ireland. It wasn't popular at first, but it grew during the Great Famine of 1845–1849. This famine caused terrible problems and showed how badly the authorities responded.

The spark for the Young Irelander Revolution came in 1848 when the British Parliament passed the "Crime and Outrage Bill." This law was basically a declaration of military rule in Ireland. It was meant to stop the growing Irish nationalist movement.

In response, the Young Ireland Party started its rebellion in July 1848. They gathered landowners and tenants to their cause. But their first big fight against the police was a failure. A long gunfight with about 50 armed police ended when more police arrived. After the Young Ireland leaders were arrested, the rebellion collapsed, though some fighting continued for another year. It is sometimes called the Famine Rebellion.

Spain

No revolution happened in Spain in 1848, but something similar did. At this time, Spain was going through the Second Carlist War. The European revolutions happened when Spain's political system faced much criticism. By 1854, a radical-liberal revolution and a conservative-liberal counter-revolution had both occurred.

Since 1833, Spain had been ruled by a conservative-liberal parliamentary monarchy, similar to France's. To keep absolute monarchs out of power, two liberal parties took turns ruling: the center-left Progressive Party and the center-right Moderate Party. But after ten years of rule by the Moderates, they made changes to the constitution in 1845. This made people fear that the Moderates wanted to team up with absolute rulers and keep the Progressives out forever. The left wing of the Progressive Party, which had ties to radical ideas, began to push for big changes to the monarchy, like the right for all men to vote.

The European Revolutions of 1848 and the French Second Republic made the Spanish radical movement adopt ideas that didn't fit with the current system, like wanting a republic. This led the Radicals to leave the Progressive Party and form the Democratic Party in 1849.

Over the next few years, two revolutions happened. In 1854, the conservative Moderates were removed from power by an alliance of Radicals, Liberals, and liberal Conservatives. In 1856, the more conservative part of this alliance started a second revolution to remove the republican Radicals. This led to another 10-year period of rule by conservative-liberal monarchists.

Together, these two revolutions were like echoes of the French Second Republic. The Spanish Revolution of 1854, a revolt by Radicals and Liberals against the unfair monarchy, mirrored the French Revolution of 1848. The Spanish Revolution of 1856, a counter-revolution by conservative-liberals under a strong military leader, was similar to Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte's coup in France.

Other European States

The United Kingdom, Belgium, the Netherlands, Portugal, the Russian Empire (including Poland and Finland), and the Ottoman Empire did not have major revolutions in 1848. Sweden and Norway were also little affected. Serbia, though part of the Ottoman state, actively supported Serbian revolutionaries in the Habsburg Empire.

In some countries, uprisings had already happened, asking for similar changes as in 1848, but with little success. This was true for the Kingdom of Poland, which had rebellions before or after 1848, but not during it.

In other countries, the calm was partly because they had already gone through revolutions or civil wars in previous years. So, they already had many of the reforms that revolutionaries elsewhere were demanding in 1848. This was largely the case for Belgium (the Belgian Revolution in 1830–1831); Portugal (the Liberal Wars of 1828–1834); and Switzerland (the Sonderbund War of 1847).

In still other countries, the lack of unrest was partly because governments acted to prevent it. They gave some reforms that revolutionaries elsewhere were demanding. This was true for the Netherlands, where King William II decided to change the Dutch constitution to reform elections and willingly reduce the monarchy's power. The same could be said for Switzerland, where a new constitution was introduced in 1848. This Swiss Federal Constitution was a kind of revolution, setting up Swiss society as it is today.

While no major political upsets happened in the Ottoman Empire itself, there was unrest in some of its smaller states. In Serbia, feudalism was ended, and the power of the Serbian prince was reduced with the 1838 Constitution.

Other English-Speaking Countries

In the United Kingdom, the middle classes were made happier by getting more voting rights in 1832. But the Chartist movement, which demanded more rights for working people, reached its peak with a peaceful petition to Parliament in 1848. The repeal of the "Corn Laws" (tariffs on imported grain) in 1846 also calmed some working-class anger.

In the Isle of Man, there were ongoing efforts to reform the self-elected House of Keys, but no revolution took place. Some reformers were encouraged by events in France.

In the United States, opinions were divided. Democrats and reformers were in favor of the revolutions, though they were upset by the violence. Conservatives, especially Whigs, southern slaveholders, and Catholics, were against them. About 4,000 German exiles arrived and some became strong Republicans in the 1850s, like Carl Schurz. Lajos Kossuth toured America and was applauded, but he didn't get volunteers or financial help.

After rebellions in 1837 and 1838, 1848 in Canada saw the creation of responsible government in Nova Scotia and The Canadas. These were the first such governments in the British Empire outside the United Kingdom. This development is linked to the revolutions in Europe. Canada's approach was to "talk their way out of the empire's control system and into a new democratic model." This created a stable democratic system that still exists today. Opposition to responsible government led to riots in 1849, including the burning of the Parliament Buildings in Montreal. But unlike counter-revolutionaries in Europe, they failed.

Latin America

In Spanish Latin America, the Revolution of 1848 appeared in New Granada (now Colombia). Colombian students, liberals, and thinkers demanded the election of General José Hilario López. He took power in 1849 and started big reforms. He ended slavery and the death penalty, and gave freedom of the press and religion. The unrest in Colombia lasted three decades, with four civil wars and 50 local revolutions between 1851 and 1885.

In Chile, the 1848 revolutions inspired the 1851 Chilean revolution.

In Brazil, the Praieira Revolt in Pernambuco lasted from November 1848 to 1852. Unfinished conflicts from earlier times and local resistance to the new Brazilian Empire helped start this revolution.

In Mexico, the conservative government lost California and half its territory to the United States in the Mexican–American War (1845–1848). Because of this disaster and ongoing stability problems, the Liberal Party started a reform movement. This movement led liberals to create the Plan of Ayutla in 1854. This plan aimed to remove the conservative president, Antonio López de Santa Anna, from power. It was the start of the Liberal Reform in Mexico. It caused revolts in many parts of Mexico, leading to Santa Anna's resignation. The next presidents were liberals. The new government then created the 1857 Mexican Constitution, which brought many liberal reforms. These reforms took away religious property and aimed to help the economy and stabilize the new republic. The reforms led directly to the Three Years War (1857). The liberals won this war, but the conservatives asked the French government for a European monarch. This led to the Second French intervention in Mexico, making Mexico a client state of France (1863–1867) under Maximilian I.

What Changed After 1848

Historian Priscilla Robertson says that many goals of the 1848 revolutionaries were achieved by the 1870s. But she notes that the credit often goes to the enemies of the revolutionaries. For example, a third French Republic was created, Germany and Italy were united, Hungary gained more freedom, Russian serfs were freed, and British working classes gained more rights.

Liberal democrats saw 1848 as a step towards democracy, ensuring liberty, equality, and fraternity in the long run. For nationalists, 1848 was a time of hope, when new nations tried to break free from old empires. But the results weren't as complete as many hoped. Communists said 1848 was a betrayal of working-class goals by the middle class, who didn't care about the workers' demands. Many historians agree that the revolutions were a "bourgeois revolution" (middle-class revolution). Middle-class fears and differences between middle-class revolutionaries and radicals led to the revolutions' failure.

Many governments after 1848 partly reversed the revolutionary changes and increased control and censorship. In the Austrian Empire, laws were passed that removed basic rights, and arrests increased greatly. Russia's rule after 1848 was very strict, with more secret police and stricter censorship. In France, works by famous writers were seized.

In the ten years after 1848, not much seemed to have changed. Many historians thought the revolutions were a failure because there weren't many lasting structural changes. More recently, Christopher Clark has said that the period after 1848 was dominated by a "revolution in government." Karl Marx was disappointed that the revolutions were mostly about the middle class. He believed the working class should keep pushing for change until they could take power.

Governments after 1848 had to manage public opinion more effectively. This led to more government agencies controlling the press. However, some revolutionary movements did have immediate successes, especially in the Habsburg lands. Austria and Prussia ended feudalism by 1850, which improved the lives of peasants. European middle classes gained political and economic power over the next 20 years. France kept the right for all men to vote. Russia later freed its serfs in 1861. The Habsburgs finally had to give Hungarians more self-rule in 1867. The revolutions also inspired lasting reforms in Denmark and the Netherlands.

About 4,000 exiles fled to the United States to escape the harsh crackdowns. These emigrants were known as the Forty-Eighters.

Images for kids

-

Louis Blenker (Germany)

-

Alexander Schimmelfennig (Germany)

-

Carl Schurz (Germany)

-

Franz Sigel (Germany)

-

August Willich (Germany)

-

Alexander Asboth (Hungary)

-

Lajos Kossuth (Hungary)

-

Albin Francisco Schoepf (Poland, Hungary)

-

Julius Stahel (Hungary)

-

Charles Zagonyi (Hungary)

-

Thomas Francis Meagher (Ireland)

-

Giuseppe Garibaldi (Italy)

-

Goffredo Mameli (Italy)

-

Giuseppe Mazzini (Italy)

-

Włodzimierz Krzyżanowski (Poland)

See also

In Spanish: Revoluciones de 1848 para niños

In Spanish: Revoluciones de 1848 para niños

- Age of Revolution

- Revolutionary Spring: Fighting for a New World 1848–1849 by Christopher Clark

- Colour Revolutions

- Democracy in Europe

- Protests of 1968

- Revolutions of 1830

- Revolutions of 1917–1923

- Revolutions of 1989

- Arab Spring