Colour revolution facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Colour revolutions |

|

|---|---|

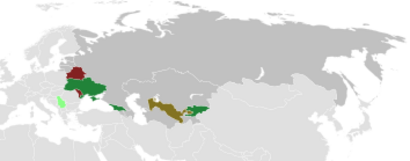

Map of the colour revolutions

Revolution successful Revolution unsuccessful Protests' status as part of the colour revolutions disputed |

|

| Location | |

| Caused by |

|

| Methods |

|

| Resulted in |

|

The colour revolutions were a series of mostly peaceful protests. They led to changes in government and society in countries that used to be part of the Soviet Union or Yugoslavia. These events happened in the early 2000s. The main goal was to create democratic governments, similar to those in Western countries.

These revolutions often started because people believed election results were fake. A key part of these movements was using the internet to communicate. Also, many non-government groups played a big role in organizing the protests. Some of these movements successfully removed the old governments. Examples include the Bulldozer Revolution in Serbia (2000) and the Rose Revolution in Georgia (2003). Others are the Orange Revolution in Ukraine (2004), the Tulip Revolution in Kyrgyzstan (2005), and the Velvet Revolution in Armenia (2018).

Contents

How Did These Revolutions Start?

Student Power and Peaceful Protests

The first big student movement was called Otpor! (meaning 'Resistance!'). It started in Serbia in 1998. Students began protesting against their leader, Slobodan Milošević, during the Kosovo War. Many of these students had protested before. Police often arrested or beat them.

Despite this, Otpor! launched a campaign called Gotov je (meaning 'He's finished'). This campaign encouraged many Serbians to oppose Milošević. It helped lead to his defeat in 2000.

Students from Otpor! later inspired and trained young people in other countries. These included Kmara in Georgia, PORA in Ukraine, and Zubr in Belarus. These groups strongly believed in peaceful resistance. They followed the ideas of Gene Sharp, who wrote about non-violent action.

Famous Colour Revolutions

Serbia's Bulldozer Revolution

In the year 2000, people who opposed the government in Serbia worked together. They encouraged many citizens to vote. However, the election results were questioned. The government said the opposition candidate, Vojislav Koštunica, didn't win enough votes. But many believed he had won clearly.

Because of these doubts and the destruction of election papers, the opposition accused the government of cheating. Protests started in the capital city, Belgrade. These protests eventually led to the removal of Slobodan Milošević from power.

The youth movement Otpor! supported these protests. These events are often seen as the first example of a peaceful revolution in the region. Even though the protesters didn't use a specific color, their slogan "Gotov je" (He's finished) became a symbol of their success. The protests are called the Bulldozer Revolution. This is because protesters used a large construction vehicle to break into a government building.

Georgia's Rose Revolution

The Rose Revolution happened in Georgia after a disputed election in 2003. This led to the removal of Eduard Shevardnadze. New elections were held in 2004, and Mikhail Saakashvili became the new leader.

The Adjara Mini-Revolution

After the Rose Revolution, there was another smaller protest in Georgia in 2004. It's sometimes called the "Second Rose Revolution." This event led to the leader of the Adjara region, Aslan Abashidze, leaving his position.

Ukraine's Orange Revolution

The Orange Revolution took place in Ukraine after a disputed presidential election in 2004. The original election results were cancelled. A new vote was held, and the opposition leader, Viktor Yushchenko, became president. He defeated Viktor Yanukovych.

Kyrgyzstan's Tulip Revolution (2005)

The Tulip Revolution in Kyrgyzstan (also called the "Pink Revolution") was more violent than the others. It followed a disputed election in 2005. Unlike other "colour revolutions," this one was less organized. Protesters in different areas used the colors pink and yellow for their demonstrations.

Moldova's Protests (2009)

In 2009, there were protests in Moldova after a parliamentary election. The opposition claimed the election was unfair. Before the election, the media seemed to favor the ruling party. Also, there were concerns about the voter lists. European observers noted "undue administrative influence" in the election.

People were also upset with President Vladimir Voronin. He was supposed to step down due to term limits but hinted he would stay involved in politics. This made people worry there would be no real change. Many people in Moldova wanted closer ties with Europe. Moldova was one of the poorest countries in Europe. International groups had criticized the government for not fighting corruption and limiting press freedom.

The government tried to say other countries were involved in the protests, but there was little proof. Thousands of people protested in the capital, Chișinău. They chanted things like "We want Europe" and "Down with Communism." Social media helped organize the protests. The government even cut off internet access in the capital. The president's reaction was criticized. He used secret police, arrested many people, and limited media.

One of the main demands of the protesters was met. The president agreed to recount the votes. Then, in July 2009, a new election was held. Opposition parties won a small majority of the votes. This was seen as a big success for the parties that wanted closer ties with Europe. Many believed the public's anger at how the government handled the April protests helped the opposition win. The deputy leader of the Liberal Party said, "Democracy has won." The opposition parties formed a new government, moving the old ruling party into opposition.

Armenia's Velvet Revolution (2018)

In 2018, Armenia had a peaceful revolution. It was led by a member of parliament, Nikol Pashinyan. He opposed the idea of Serzh Sargsyan becoming Prime Minister again. Sargsyan had already been president and prime minister. People were worried that Sargsyan would have too much power.

Protests happened across the country, especially in the capital, Yerevan. Armenians living in other countries also showed their support. Pashinyan was arrested but released the next day. Sargsyan then stepped down as Prime Minister. His party decided not to put forward another candidate. Protests continued for over a month. Hundreds of thousands of people joined the demonstrations in Yerevan. Pashinyan called it a Velvet Revolution. Later, parliament voted, and Pashinyan became the Prime Minister of Armenia.

What Made These Revolutions Successful?

A political expert named Michael McFaul found some common things that helped these colour revolutions succeed:

- The country had a leader who was somewhat strict, but not completely controlling.

- The current leader was not popular with the people.

- The groups opposing the government were united and well-organized.

- They could quickly show that election results were fake.

- There were enough independent news sources to tell people about the fake votes.

- The opposition could gather thousands of people to protest election fraud.

- There were disagreements or divisions among the government's security forces.

See Also

- People power

- Civil resistance

- Revolutions of 1989

- Arab Spring

- Spring Revolutions (disambiguation)

- United States involvement in regime change

- Post-Soviet conflicts

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |