Classical radicalism facts for kids

Radicalism was a political movement that wanted big changes in society. It was part of liberalism in the late 1700s and early 1800s. This movement helped shape modern ideas like social liberalism and progressivism. Sometimes it's called "radical liberalism" or "classical radicalism" to tell it apart from other types of radical politics. Its first ideas came from groups like the Levellers and Radical Whigs during the English Civil War.

In the 1800s, especially in the United Kingdom, Europe, and Latin America, "radical" meant a progressive liberal idea. It was inspired by the French Revolution. Radicalism became important in the 1830s with the Chartists in the UK and the Belgian Revolution in Belgium. It then spread across Europe during the Revolutions of 1848.

Unlike older liberal ideas, radicalism pushed for major changes to the electoral system. They wanted to let more people vote. Radicals also supported ideas like republicanism (a government without a king), secularism (keeping government and religion separate), and freedom of the press.

In 19th-century France, radicals were seen as the far-left. They were different from more traditional liberals and monarchists. By 1901, they formed the Republican, Radical and Radical-Socialist Party. This was France's first big political party outside of parliament. It became a leading party in the French Third Republic until 1940. The success of French Radicals encouraged similar groups in other countries to form their own parties.

Before socialism became a major political idea, radicalism was the left-wing part of liberalism. As new ideas like social democracy grew, some radicals became more like conservative liberals. Others joined forces with social democrats. After World War II, radical parties mostly faded away in Europe. However, some countries like Denmark, France, and Italy still have radical parties. Latin America also has its own radical traditions, for example, in Argentina and Chile.

Contents

What Radicalism Wanted

Radicalism and Liberalism

Both Enlightenment ideas, liberalism and radicalism, wanted to free people from old traditions. Liberals thought it was enough to create individual rights. But radicals wanted to change institutions, society, and education. They believed this would help everyone actually use those rights. So, radicalism went beyond just wanting freedom. It also pushed for equality, meaning fairness for all, like in the French motto "Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité" (Liberty, Equality, Fraternity).

In some places, radicalism was a smaller part of the Liberal political group, like the Radical Whigs in England. Sometimes, these radical liberals were very strict in their beliefs. Other times, they were more flexible. In other countries, radicalism had enough support to form its own parties. This happened in places like Switzerland, Germany, Bulgaria, Denmark, Italy, Spain, the Netherlands, and in Latin America like Argentina and Chile.

In Victorian era Britain, radicals were the left wing of the Liberal group. They often disagreed when the more traditional Liberals resisted democratic changes. In Ireland, radicals lost faith in slow parliamentary changes. They broke away from liberals and sought a democratic republic through independence and uprising. In France, radicalism was seen as a separate political force, to the left of liberalism but to the right of socialism. Over time, as new left-wing parties formed, some radicals moved closer to the liberal group.

The difference between radicals and liberals became clearer in the mid-20th century. In 1923-24, French Radicals created an international group for radical parties. After World War II, this group was not reformed. Instead, a more conservative Liberal International was set up. This showed the end of radicalism as a fully independent political force in Europe. However, some countries like France and Switzerland had important radical parties until the 1950s and 1960s. Many European parties today that are called "social-liberal" have historical links to radicalism.

Radicalism in Different Countries

United Kingdom

The word "radical" in politics is often linked to Charles James Fox. He was a leader of the left wing of the Whig party in England. He liked the big changes happening in France, like letting all men vote. In 1797, Fox called for a "radical reform" of the electoral system. This led to the term being used for anyone who supported changes to parliament.

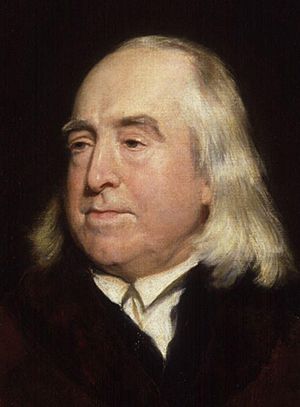

At first, radical ideas were mostly among the upper and middle classes. But in the early 1800s, "popular radicals" brought workers into the movement. They faced harsh government actions. More respected "philosophical radicals" followed the ideas of Jeremy Bentham. They strongly supported parliamentary reform. By the mid-1800s, parliamentary Radicals joined with others to form the Liberal Party. They eventually achieved changes to the voting system.

How it Started

The Radical movement began when there was tension between the American colonies and Great Britain. Early radicals were upset with the House of Commons. They wanted better representation in parliament, similar to the ideas of the Levellers from the English Civil War. After the English Restoration of the monarchy, these ideas had been put aside.

Even after the Glorious Revolution of 1688, which gave parliament more power, the king still had a lot of influence. The Parliament of Great Britain was controlled by rich families. Voting was limited to property owners. Many voting areas, called "rotten boroughs," were outdated. Major cities had no representation. This unfairness inspired people who became known as "Radical Whigs."

William Beckford helped start interest in reform in London. The "Middlesex radicals" were led by John Wilkes. He opposed the war with the colonies. In 1769, he started the Society for the Defence of the Bill of Rights. This group believed every man should have the right to vote. For the first time, middle-class radicals got support from London's working people.

Major John Cartwright also supported the colonists. In 1776, he published a pamphlet called Take Your Choice! He called for yearly parliaments, secret voting, and all men being able to vote. In 1780, a reform plan was made by Charles James Fox and Thomas Brand Hollis. It included calls for the six points later used by the Chartists.

The American Revolutionary War ended in defeat for King George III. In 1782, he had to appoint a government that wanted to limit his power. In 1785, Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger tried to change voting areas, but his plan was defeated.

Public Protests

After the French Revolution of 1789, Thomas Paine wrote The Rights of Man (1791). It was a response to Edmund Burke's book against the French Revolution. Mary Wollstonecraft also wrote A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. These writers encouraged many people to support democratic reform. They also wanted to get rid of the monarchy and all special privileges.

Different groups formed within the movement. Middle-class "reformers" wanted to expand voting rights for business interests. "Popular radicals" from the middle and working classes pushed for wider rights and help for the poor. "Philosophical radicals" followed Jeremy Bentham's ideas. They strongly supported parliamentary reform but often disagreed with the methods of the "popular radicals."

In Ireland, the United Irishmen movement took a different path. They added the idea of civic nationalism to the French Revolution's ideas of a secular republic. Irish Radicals felt that British parliament could not bring about the deep democratic changes they wanted. So, they turned their movement into a republican form of nationalism. This aimed for equality and freedom through armed revolution, sometimes with French help.

Popular Radicals quickly went further than Paine. Newcastle schoolmaster Thomas Spence called for land to be owned by the nation. Radical groups appeared, like the London Corresponding Society of workers formed in 1792. They called for the right to vote. Another group, the Scottish Friends of the People, held a British meeting in Edinburgh in 1793. They demanded all men be able to vote and supported the French Revolution. While these movements were small, they were the first time working men organized for political change.

The government reacted strongly. They jailed Scottish radicals and temporarily stopped habeas corpus in England. They passed the Seditious Meetings Act 1795, which required a license for public meetings of 50 or more people. During the Napoleonic Wars, the government took harsh steps against feared unrest. The corresponding societies ended, but some radicals continued in secret. Irish supporters formed secret groups to overthrow the government. In 1812, Major John Cartwright formed the first Hampden Club. It aimed to bring together middle-class moderates and working-class radicals.

After the Napoleonic Wars, the Corn laws (1815-1846) and bad harvests caused more unhappiness. The writings of William Cobbett were important. Speakers like Henry Hunt pointed out that only three out of a hundred men could vote. Writers like William Hone and Thomas Jonathan Wooler spread their ideas despite government laws against political writings. Radical riots in 1816 and 1817 were followed by the Peterloo massacre of 1819. The Six Acts of 1819 limited the right to protest. In Scotland, protests led to an attempted general strike and workers' uprising in the "Radical War" of 1820.

Political Changes

Economic conditions improved after 1821. The United Kingdom government made some economic and criminal law changes. In 1823, Jeremy Bentham helped start the Westminster Review. This journal shared the "philosophical radicals'" idea that good actions should help the greatest number of people.

The Whigs gained power. Despite some defeats, the Reform Act 1832 was passed with public support and protests. This law gave voting rights to the middle classes, but it didn't meet all radical demands. The Whigs introduced reforms based on philosophical radical ideas. They ended slavery and changed the Poor Law in 1834. After the 1832 Reform Act, a small number of parliamentary Radicals joined the Whigs in parliament. By 1839, they were informally called "the Liberal party."

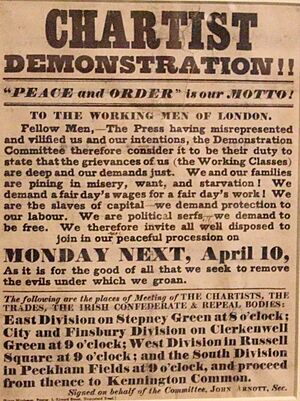

Chartists

From 1836, working-class Radicals united around the Chartist movement. They wanted electoral reform, which was written in the People's Charter. This charter called for six main points: universal suffrage (all men voting), equal-sized voting districts, secret ballot, no property requirement for Parliament members, pay for Members of Parliament, and yearly parliaments. Chartists also spoke about economic problems. However, their large protests and petitions to parliament were not successful.

Later, the middle-class Anti-Corn Law League took up their cause. Founded by Richard Cobden and John Bright in 1839, this group opposed taxes on imported grain. These taxes raised food prices, helping landowners but hurting ordinary people.

Liberal Reforms

The parliamentary Radicals joined with the Whigs and some anti-protectionist Torys to form the Liberal Party by 1859. Calls for parliamentary reform grew by 1864, with support from John Bright and the Reform League.

When the Liberal government tried to pass a small reform bill, it was defeated. The Tories, led by Benjamin Disraeli, then took office. Disraeli's Reform Act 1867 almost doubled the number of voters, even giving working men the right to vote.

Radicals had worked hard for the working classes. Because of this, they gained strong loyalty. British trade unionists elected to Parliament from 1874 to 1892 saw themselves as Radicals. They were called Lib-Lab candidates. These radical trade unionists formed the basis for what later became the Labour Party.

Belgium

The areas that are now Belgium became part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in 1815. There were religious and economic tensions between the Dutch north and the Belgian south. In the 1820s, young Belgians, influenced by French ideas, criticized the Dutch monarchy. The king had too much power, and ministers were not accountable to parliament. Freedom of the press and association were limited. The mostly Catholic south had two-thirds of the population but the same number of parliament seats as the smaller Protestant north. Belgian Radicals, like those in France, felt that a simple list of rights was not enough.

In 1830, a liberal revolution in France overthrew the king. Within a month, a revolt started in Brussels and spread. After Belgium became independent, the Constitution of 1831 created a constitutional monarchy and a parliamentary system. It also listed basic civil rights, inspired by the French Declaration of the Right of Man.

Like in Britain, Belgian Radicals continued to work within the Liberal Party. They campaigned in the 1800s to expand voting rights, which were limited by property ownership. Voting rights were expanded in 1883, and all men could vote by 1893. Women gained the right to vote in 1919. After this, radicalism became a smaller political force in Belgium, as a strong social-democratic party emerged.

France

In the 1800s, French Radicals were the far-left political group. They were to the left of "opportunists" (conservative-liberal republicans) and monarchists.

After the Napoleonic Wars and until 1848, it was illegal to openly support a republic. Some republicans accepted working within the monarchy. But those who believed the French Revolution needed to be finished with a republic based on democracy and universal voting called themselves "Radicals." This term meant 'Purists'.

Under the Second Republic (1848–1852), Radicals formed a group in parliament called The Mountain. They wanted a "social and democratic republic." When Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte launched his military coup, Radicals across France rose up to defend the republic. This event made French Radicalism watchful against anyone who seemed to want to overthrow the democratic government.

After democracy returned in 1871, Radicals became a strong political force. Led by Georges Clemenceau, they argued that other liberals had moved away from the French Revolution's ideals. Radicals believed they were the true followers of the 1791 revolution. In 1881, they presented their plan for social reforms. From then on, the main Radical Party aimed to have 'no enemies to the left' of the Republic. They allied with any group that wanted social reform and accepted the parliamentary republic.

Radicals were not yet a formal political party, but they worked together in parliament. The first half of the Third Republic saw events that made them fear a far-right takeover. These included Marshall Mac-Mahon's self-coup in 1876 and the Dreyfus Affair in the 1890s. Radicals came to power in a coalition government in 1899, then in their own governments from 1902. They finally put their reforms into action, such as the separation of Church and State and secret ballotting. To make sure these changes lasted, they united local Radical groups into a political party: the Radical-Socialist Party. This was the first major modern political party in French history.

Thinkers played a big role. Émile Chartier (1868–1951), known as "Alain," was a key radical thinker. He stressed individualism, protecting citizens from the state. He warned against all forms of power, like military or economic power. He valued small farmers, small shopkeepers, and small towns.

The Radical–Socialist Party was the main government party of the Third Republic from 1901 to 1919. It also led governments in the 1920s and 1930s.

The party lost trust after 1940 because many of its members voted to create the Vichy regime. However, some prominent Radicals, like Jean Zay and Maurice Sarraut, were killed by the regime's police. Others, like Jean Moulin, joined the resistance movement to bring back the Republic.

After World War II, the Democratic and Socialist Union of the Resistance was formed. It combined French Radicalism with the good reputation of resistance members.

In the 1950s, Pierre Mendès-France tried to rebuild the Radical Party. He wanted it to be an alternative to other parties and opposed Gaullism, which he feared was another attempt at a right-wing takeover. During this time, Radicals often governed as part of a coalition of centrist parties.

The creation of the Fifth Republic in 1958 and the rise of a two-party system (Socialists and Gaullists) ended the need for an independent Radical party. The Radical Party split. Mendès-France left in 1961 and joined a small social-democratic party. A decade later, another group broke away in 1972 to form the Radical Party of the Left. This group works closely with the Socialist Party. The rest of the original Radical Party became a liberal-conservative party. It allied with other liberal centre-right groups.

Ireland

Irish republicanism was influenced by French radicalism. Examples of these historical radicals include the United Irishmen in the 1790s, Young Irelanders in the 1840s, and the Fenian Brotherhood in the 1880s. Later, Sinn Féin and Fianna Fáil in the 1920s also showed these influences.

Japan

Japan's radical-liberalism during the Empire of Japan was different because it opposed the government's political control. It resisted ideas like republicanism. The radical liberal movement in Japan was not separate from socialism and anarchism at that time, unlike in the West. Kōtoku Shūsui was a well-known Japanese radical liberal.

After World War II, Japan's left-wing liberalism became a "peace movement." It was largely led by the Japan Socialist Party.

United States

One part of the American radical movement was Jacksonian democracy. This movement supported political equality among white men.

Radicalism was also seen in the Radical Republicans. This group included people who wanted to end slavery and democratic reformers. Some were strong supporters of trade unions.

Later, classical Radicalism was expressed by the Populist Party. This party was made up of farmers from the western and southern United States. They supported ideas like government control of railroads, and expanding voting rights.

Europe and Latin America

In continental Europe and Latin America, radicalism grew as an idea in the 1800s. It meant supporting a republican government, universal male voting rights, and especially anti-clericalism (policies against the power of the church). This was seen in France, Italy, Spain, Chile, and Argentina.

In German-speaking countries, this movement is called Freisinn (meaning "free mind" or "freethought"). Examples include the German Freeminded Party and the Free Democratic Party of Switzerland.

"Freethinker" parties, mainly in the Netherlands, Scandinavia, and German-speaking countries, included:

- In Switzerland:

* The Radical movement (or "Free-thinking" movement) started around 1830. It became the main political force under the 1848 Constitution. * The Radical-Democratic Party (1894–2009) started as a centre-left party but moved towards the centre-right. * The Radical-Liberal Party (PLR) was formed in 2009 by merging the Radical-Democratic Party with a smaller, more right-leaning party.

- In the Netherlands:

* Radical League (1882–1901) * Free-thinking Democratic League (1901–1946)

- In Germany, there were several Radical parties:

* The German Free-minded Party (1884–1893), which split into two groups. * These groups later merged to form the Progressive People's Party (1910–1918). * This was reformed as the German Democratic Party (1918–1930).

- In Denmark:

* The current Liberal Party started as a radical party in 1870. Its Danish name is Venstre, meaning 'Left'. When it became more conservative, the Radical wing split in 1905 to form a new party, called Radikale Venstre ('Radical Left').

- In Norway:

* The current Liberal Party started as a radical party in 1884. Its Norwegian name is Venstre, meaning 'Left'.

In Mediterranean Europe, Radical parties were often called 'Democratic' or 'Republican' parties:

- In France, radicalism was closely tied to republicanism. Radical parties were often simply called 'republicans'. The election of Alexandre Ledru-Rollin in 1841 is seen as the start of the radical-republican movement. Over time, Radicals would form a party on the left, then it would move to the center. This would cause its left wing to split off and form a new main Radical party. This meant there were usually two rival Radical parties.

* La Montagne (1848–1851) was the first parliamentary group for France's radical republicans. * The Republican Union (1871–1884), led by Léon Gambetta, was a successor. Its members included Louis Blanc and Victor Hugo. * Radical Left (1881–1940) was a parliamentary group formed by strong anti-church radicals. It was important in centre-left governments. Its leader, Georges Clemenceau, led the government during World War I. * The Radical-Socialist Party (1901–1940) was the most famous French radical party. It was the main political force in France for many years. * After World War II, the Radical-Socialist Party and other radical groups were weakened. They mostly joined with other liberal parties to form a centre-right group. In 2017, the Radical-Socialist Party merged with the Radical Party of the Left to form the Radical Movement.

- In Spain, Radicalism appeared as various 'democratic', 'progressive', 'republican', and 'radical' parties.

* The Progressive Party (1835–1869). * The Democratic Party (1849–1869). * The Radical Republican Party (1908–1936) became the main radical party of the Second Republic (1931–1936/39).

- In Italy:

* Action Party, formed by Risorgimento leaders like Giuseppe Mazzini. They wanted a united, secular Italian republic with universal voting rights. * "Historical Far Left" (1867/77–1904). * Italian Republican Party (founded 1895). * Italian Radical Party (1904–1922). * Radical Party (1955–1989). * Transnational Radical Party (1989–present). * Italian Radicals (2001–present).

Serbia and Montenegro

Radicalism played a key role in creating parliament and the modern Serbian state. The People's Radical Party (formed 1881) was the strongest political party in the Kingdom of Serbia. The 1888 Constitution of the Kingdom of Serbia, which created an independent nation and formal parliamentary democracy, was very advanced thanks to radical contributions. It was known as The Radical Constitution. In 1902, the Independent Radical Party split off. The original People's Radical Party then moved away from progressive ideas towards right-wing nationalism.

In Montenegro, a People's Party was formed in 1907. It was the country's first political party and remained the largest until the country joined Yugoslavia.

|

See also

In Spanish: Radicalismo para niños

In Spanish: Radicalismo para niños

- Anti-clericalism

- Classical liberalism

- Cultural radicalism

- Conservative liberalism, a part of the 19th-century liberal tradition.

- Danish Social Liberal Party, literally The Radical Left

- Italian Radicals

- Left-libertarianism

- Progressivism

- Radical democracy

- Radical Party (France)

- Radical Party of the Left

- Radicals (UK)

- Transnational Radical Party

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |