William Cobbett facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

William Cobbett

|

|

|---|---|

William Cobbett, portrait in oils possibly by George Cooke, c. 1831 National Portrait Gallery (London)

|

|

| Born | 9 March 1763 Farnham, England |

| Died | 18 June 1835 (aged 72) Normandy, Surrey, England |

| Occupation | Pamphleteer, journalist, soldier |

| Education | Gray's Inn |

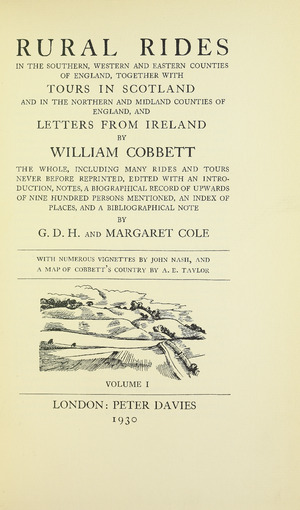

| Notable works | Rural Rides |

| Member of Parliament for Oldham |

|

| In office 1832–1835 |

|

| Succeeded by | John Frederick Lees |

| Personal details | |

| Political party | Radical |

William Cobbett (born March 9, 1763 – died June 18, 1835) was an English writer, journalist, politician, and farmer. He was born in Farnham, Surrey. Cobbett was a strong supporter of farmers and wanted to make big changes to the government. He aimed to help poor farm workers and small landowners. He believed in lower taxes and higher wages. He also wanted to stop the practice of "rotten boroughs," which were areas with very few voters but still had a lot of power in Parliament.

Cobbett was against people who got rich from government jobs without doing much work. His ideas helped lead to the Reform Act 1832, which changed how Parliament worked. He even became a Member of Parliament for Oldham. He wrote about many topics, from politics to religion. His most famous book is Rural Rides. He believed that the world could support more people if the economy was managed better.

Contents

- William Cobbett's Early Life (1763–1791)

- Life in France and the United States (1792–1800)

- Return to England and The Political Register (1800–1810)

- Time in Prison (1810–1812)

- The "Two-Penny Trash" (1812–1817)

- Time in the United States (1817–1819)

- Later Life and Political Work (1819–1835)

- William Cobbett's Legacy

- Images for kids

- See also

William Cobbett's Early Life (1763–1791)

William Cobbett was born in Farnham, Surrey, on March 9, 1763. He was the third son of George Cobbett, who was a farmer and also ran a pub. His mother was Anne Vincent. William learned to read and write from his father. He started working at a very young age. He once said, "I do not remember a time when I did not earn my living." His first job was scaring birds away from crops.

He worked as a farm helper at Farnham Castle. He also spent a short time as a gardener in the King's garden at Kew. Growing up in the countryside made him love gardening and hunting his whole life.

In May 1783, he traveled to London. He worked for a few months as a clerk. Then, in 1783, he joined the army, the 54th (West Norfolk) Regiment of Foot. During his free time, he studied and improved his English grammar. From 1785 to 1791, Cobbett was stationed with his army group in New Brunswick, which is now part of Canada. He sailed from Gravesend in England to Halifax, Nova Scotia. He was in different places in New Brunswick, like Saint John and Fredericton. He was promoted through the ranks and became a sergeant major, which is a very important non-commissioned officer.

Cobbett returned to England with his regiment in November 1791. He left the army in December 1791. In February 1792, he married Anne Reid (1774–1848) in Woolwich. She was American and he had met her while in the army. They had six children: Anne, William, John, James Paul, Eleanor, and Susan.

Life in France and the United States (1792–1800)

While in the army, Cobbett noticed that some officers might be dishonest. He collected proof, but his complaints were not listened to. In 1792, he wrote a pamphlet called The Soldier's Friend. It complained about the low pay and harsh treatment of soldiers. He felt he might be punished for this, so he left Britain for France in March 1792.

Cobbett planned to stay in France for a year to learn French. But because of the French Revolution and wars, he sailed to the United States in September 1792.

Cobbett arrived in Wilmington and later settled in Philadelphia in 1793. He first earned money by teaching English to French people and translating books. He said he became a political writer by chance. One of his students read an article that criticized Britain. Cobbett disagreed strongly and decided to write to defend his country. His first published work, Observations on the Emigration of Dr. Priestley (1794), was a strong attack on a person who had moved to America.

In 1795, Cobbett wrote A Bone to Gnaw for the Democrats. This book criticized the Democratic Party, which was friendly to France. He used the pen name "Peter Porcupine" for his writings. He liked this name because someone had compared him to a porcupine. He supported the Federalists, led by Alexander Hamilton, because they were more friendly to Britain.

In 1796, he started a monthly newspaper called The Censor. Later, he started Porcupine's Gazette, a daily newspaper that ran from 1797 to 1799. A French spy named Talleyrand tried to pay Cobbett to support France, but Cobbett refused.

Cobbett opened a bookstore in Philadelphia in July 1796. He put a large picture of King George III of Britain in his shop window. Inside, he had a big painting of a British naval victory. This display caused a lot of talk. He published many pro-British writings.

When Spain joined France against Britain, Cobbett wrote angrily about it in Porcupine's Gazette. He criticized the Spanish King. The Spanish foreign minister in Philadelphia asked the U.S. government to take legal action against Cobbett for insulting the king. Cobbett was arrested in November 1797. He was tried in Pennsylvania. Even though the judge criticized him, the jury decided not to go forward with the case.

Cobbett also spoke out against a doctor named Benjamin Rush. Rush used a treatment called bleeding during a yellow fever outbreak, which Cobbett believed caused many deaths. Rush won a legal dispute against Cobbett. Cobbett did not pay the full amount he was ordered to pay. Instead, he moved to New York and then returned to England in 1800.

The British government was thankful for Cobbett's support of Britain in America. A British representative even offered him a lot of money, but Cobbett did not take it.

Return to England and The Political Register (1800–1810)

Cobbett's writings from America were reprinted in Britain. In 1800, he was invited to dinner with the Prime Minister, William Pitt. Pitt's government offered Cobbett a job editing a government newspaper, but he wanted to stay independent. He started his own newspaper, The Porcupine, in October 1800. It was not very successful, so he sold his share in 1801.

Less than a month later, he started Political Register. This newspaper was published almost every week from January 1802 until Cobbett's death in 1835. Friends had suggested the idea of a weekly newspaper and helped him get money to start it.

When Britain signed a peace agreement with France in October 1801, Cobbett was one of the main people against it. He wrote that the agreement was bad for Britain. When the peace was confirmed, Cobbett refused to light up his house windows to celebrate. A crowd attacked his house and broke the windows. When the Peace of Amiens was signed in March 1802, Cobbett again refused to celebrate. Soldiers had to protect his house from angry crowds.

War started again between Britain and France in May 1803. Napoleon planned to invade England. Cobbett immediately wrote a pamphlet called Important Considerations for the People of the Kingdom. It warned people about what would happen if France invaded. Cobbett refused payment from the government for his pamphlet. It was published anonymously in July. The Prime Minister ordered copies to be sent to every town in England, and it quickly changed public opinion.

Cobbett became good friends with a politician named Windham. They both disliked the French Revolution's ideas and loved country sports. Some religious groups wanted to stop traditional sports like bull-baiting and boxing. They wanted people to go to Sunday Schools instead. Cobbett wrote in the Register that these groups were against fun and healthy sports. He supported Windham in Parliament, who tried to stop laws against boxing and bull-baiting.

At first, Cobbett was strongly against the ideas of the French Revolution. But by 1804, he started to question the British government's policies. He worried about the huge national debt and the waste of money on jobs where people did little work. Cobbett believed these things were harming the country and causing problems between different social classes. By 1807, he was supporting reformers who wanted change.

Cobbett also published important historical documents, like records of court trials and parliamentary debates. He had to sell his share in these projects later because of money problems. These records later became known as Hansard, which is still used today to record what is said in Parliament.

In 1806, Cobbett wanted to run for Parliament in Honiton. He campaigned with another person, but they both lost. They refused to pay people for their votes, which was a common practice then. This made Cobbett even more against "rotten boroughs" and more determined to see Parliament reformed.

Time in Prison (1810–1812)

On June 15, 1810, Cobbett was found guilty of speaking out against the government. This happened after he wrote in The Register about soldiers being whipped. He spent two years in Newgate Prison. While in prison, he wrote a pamphlet called Paper Against Gold. It warned about the dangers of paper money. He also wrote many other essays and letters. When he was released, 600 people attended a dinner in his honor in London. It was led by Sir Francis Burdett, who also wanted Parliament to be reformed.

The "Two-Penny Trash" (1812–1817)

By 1815, there was a high tax on newspapers, making them very expensive. This meant that only wealthy people could afford to buy newspapers. Cobbett's newspaper only sold about a thousand copies a week. He started to criticize William Wilberforce, a famous politician. Cobbett disagreed with Wilberforce's support for certain laws and his wealth.

In 1816, Cobbett started publishing the Political Register as a pamphlet. It now cost only two pence. Its sales quickly grew to 40,000 copies a week. Critics called it "two-penny trash," a name Cobbett liked and used himself. It became the main newspaper read by working-class people.

This made Cobbett a powerful voice. In 1817, he learned that the government planned to arrest him for his writings. The government was also going to suspend a law that protected people from being held without charge. Fearing arrest, Cobbett fled to the United States again. He sailed from Liverpool to New York in March 1817, with his two oldest sons.

Time in the United States (1817–1819)

Cobbett lived on a farm on Long Island for two years. There, he wrote Grammar of the English Language. With help from a friend in London, he continued to publish the Political Register. He also wrote The American Gardener (1821), which was one of the first gardening books published in the United States.

Cobbett returned to Britain by ship in November 1819.

Later Life and Political Work (1819–1835)

Cobbett arrived back in Britain shortly after the Peterloo Massacre, a violent event where soldiers attacked peaceful protesters. He joined other reformers in criticizing the government. He was accused of speaking out against the government three times in the next few years.

In 1820, he ran for Parliament in Coventry but did not win. That year, he also started a plant nursery in Kensington. He grew many North American trees there. With his son, he also grew a special type of corn he called "Cobbett's corn." This corn grew well in England's shorter summers. To help sell it, he wrote a book called A Treatise on Cobbett's Corn (1828). He also wrote his popular book Cottage Economy (1822). This book taught people in cottages how to be self-sufficient, like how to make bread, brew beer, and raise farm animals.

Helping the English Poor and Working Class

Cobbett didn't just wait for news for his newspaper. He traveled around the country himself. He observed what was happening in towns and villages. He especially focused on the difficulties faced by people in the countryside. His famous work, Rural Rides, first appeared in his Political Register from 1822 to 1826. It was then published as a book in 1830. While writing it, Cobbett also wrote The Woodlands (1825), a book about growing trees.

Cobbett had once supported the slave trade. But after it was banned in 1807, he wrote that no one really cared about it. Later, in 1823, Cobbett published a letter to William Wilberforce. He criticized Wilberforce for supporting a law that banned workers from forming unions in Britain. Cobbett said that Wilberforce had never helped British workers, but had often acted against them. This letter was widely shared among working-class people. It helped lead to the union ban being removed in 1824.

Cobbett compared the campaign to end slavery for Black people with the "factory slavery" of British workers. He argued that Black slaves were often better fed, clothed, and housed than British workers. He believed that humane English people should focus on helping white workers first, until their situation was as good as that of Black slaves. In 1833, Cobbett voted to end slavery. However, he continued to point out that Parliament seemed to care more about Black slaves than about the suffering of British "factory slaves."

Supporting Catholic Rights

Even though he was not Catholic, Cobbett also supported Catholic Emancipation. This was a movement to give Catholics equal rights. Between 1824 and 1826, he published his History of the Protestant Reformation. This book criticized the traditional Protestant view of history. It highlighted the long and often violent persecution of Catholics in Britain and Ireland. At that time, Catholics were still not allowed to have certain jobs or be Members of Parliament.

In 1829, Cobbett published Advice To Young Men. In this book, he criticized the ideas of Thomas Robert Malthus, who believed that population growth would lead to poverty. That same year, Cobbett also published The English Gardener, which he later updated. This gardening book was well-regarded.

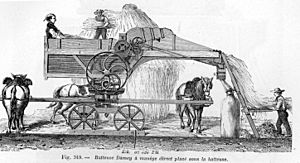

Cobbett continued to publish strong opinions in the Political Register. In July 1831, he was accused of speaking out against the government again. This was for a pamphlet called Rural War, which seemed to support the Captain Swing Riots. In these riots, people were breaking farm machines and burning haystacks. Cobbett successfully defended himself in court.

Becoming a Member of Parliament

Cobbett still wanted to be elected to the House of Commons. He lost elections in Preston in 1826 and in Manchester in 1832. But after the Reform Act 1832 was passed, Cobbett won a seat for Oldham.

In Parliament, Cobbett focused on fighting against government corruption. He also strongly opposed the 1834 Poor Law. He believed that poor people had a right to a share of the community's wealth. He thought the old Poor Law was the last right that English workers had. He felt that the new Poor Law took away this right, breaking the agreement between the government and the people. A week before he died, he wrote to a friend that he now expected big changes.

Towards the end of his life, another Member of Parliament, Thomas Macaulay, noted that Cobbett's abilities were weakening due to age. From 1831 until his death, Cobbett managed a farm called Ash in Normandy, Surrey, near his birthplace. William Cobbett died there in June 1835 after a short illness. He was buried in the churchyard of St Andrew's Church, Farnham.

William Cobbett's Legacy

William Cobbett started as a writer who wanted to keep things traditional. But he became very angry with the dishonest British government. He grew more radical and believed in ideas that gave more power to ordinary people. He wrote beautifully about rural England during the Industrial Revolution, which he did not like. Cobbett wished England could go back to the countryside life of the 1760s, when he was born.

Unlike another famous writer, Thomas Paine, Cobbett was not a "citizen of the world." He focused on what was best for England, Scotland, and Ireland. He often criticized other countries and warned them not to be rude to England. He said he identified with the Church of England partly because it "bears the name of my country."

Cobbett's writing style was so unique that it was even made fun of in a book called Rejected Addresses (1812).

Many important thinkers from different political backgrounds have praised Cobbett. These include Matthew Arnold, Karl Marx, G. K. Chesterton, and E. P. Thompson.

A story by Cobbett in 1807 helped make the phrase "red herring" popular. This term means something that distracts you from the main issue.

Cobbett's sons became lawyers and started a law firm called Cobbetts in his honor. The firm closed in 2013. His second son, John Morgan Cobbett, also became a Member of Parliament for Oldham, just like his father.

Cobbett's birthplace in Farnham, which was once a pub called The Jolly Farmer, has been renamed The William Cobbett. There is also a primary school named after him in Farnham.

After Cobbett's death, a friend named Benjamin Tilly started the Cobbett Club. Members sent requests to Parliament asking for big changes. They also created pamphlets to keep Cobbett's political ideas alive. The William Cobbett Society, based in Farnham, celebrates his life and work. They even have an annual "Rural Ride" and a lecture.

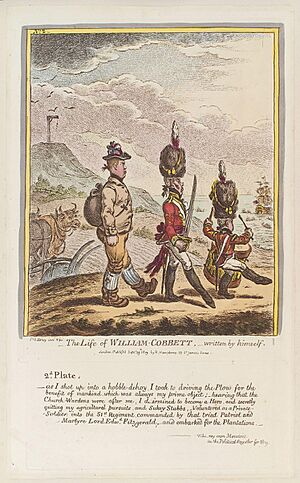

Images for kids

-

William Cobbett, portrait in oils possibly by George Cooke, c. 1831 National Portrait Gallery (London)

-

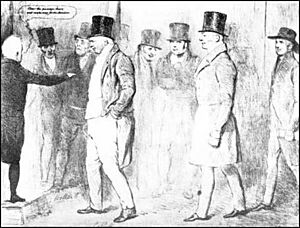

Cartoon of Cobbett enlisting in the army. From the Political Register of 1809. Artist James Gillray.

-

The introduction of horse-powered threshing machines to farms was one of the principal causes of the Swing Riots.

-

William Cobbett (left foreground), John Gully (middle) and Joseph Pease (right) (the first Quaker elected to Parliament) arriving at Westminster, during March 1833. Sketch by John Doyle.

See also

In Spanish: William Cobbett para niños

In Spanish: William Cobbett para niños

- Tilford, with an ancient oak tree described by Cobbett

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |