Swing Riots facts for kids

The Swing Riots were a big uprising in 1830. Farm workers in southern and eastern England protested against new machines and tough working conditions. It started in Kent in the summer of 1830 when people destroyed threshing machines. By December, the protests had spread across southern England and East Anglia.

The first threshing machine was broken on August 28, 1830. By late October, over 100 machines were destroyed in East Kent alone. These machines took jobs away from workers. Protesters also rioted over low wages and church payments called tithes. They attacked workhouses and tithe barns, which were symbols of their hardship. They also burned haystacks and hurt cows.

The rioters were angry at three main things. First, the tithe system made them pay money to the church. Second, the people in charge of the Poor Laws (called guardians) were seen as unfair to the poor. Third, rich farmers were lowering workers' wages and bringing in new agricultural machinery. If caught, protesters could be charged with serious crimes like setting fires or rioting. Those found guilty might be jailed, sent to Australia, or even executed.

Many things caused the Swing Riots. Historians believe the main reason was that farm workers had become much poorer over the past 50 years. A study in 2020 showed that more threshing machines led to more riots. Riots were worse where there were few other job options.

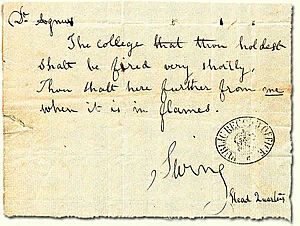

The name "Swing Riots" came from Captain Swing. This was a made-up name often signed on threatening letters sent to farmers, judges, and church leaders. Captain Swing was like a mythical leader of the movement. The name "Swing" likely referred to the swinging stick of a tool used for hand threshing. The first mention of "Swing letters" was in The Times newspaper on October 21, 1830.

Why Did the Riots Happen?

In the early 1800s, England was different from other countries because it had very few small farmers who owned their land. Laws called the Enclosure Acts made things worse for farm workers. Between 1770 and 1830, about 6 million acres of common land were fenced off. For centuries, poor people used this common land to graze animals and grow food. But now, this land was given to large landowners. This meant landless farm workers had to work only for richer neighbors for money.

During the Napoleonic Era, there were enough jobs and food prices were high, so life was okay. But after peace returned in 1815, grain prices dropped, and there were too many workers. This made life very hard.

Historians John and Barbara Hammond said that enclosure was bad for small farmers and poor villagers. Before enclosure, a poor villager might have some land. After enclosure, they had no land and only worked for others. However, some historians like G. E. Mingay noted that the areas most affected by enclosure did not have many Swing Riots. The riots were mostly in southern counties, where enclosure was less common. This might be because areas like the West Midlands had new jobs in factories and mines.

Other historians like J. D. Chambers and G. E. Mingay argued that enclosure actually meant more food for a growing population and more farm jobs overall. Modern historians Eric Hobsbawm and George Rudé found only a few riot incidents directly caused by enclosure. However, newer historians have challenged these ideas.

Without their own land, peasants could not be independent. They had to become laborers. Many moved to towns to find factory jobs.

In the 1780s, workers were hired for a whole year at special fairs. They often lived and ate with their employers. But over time, the gap between farmers and workers grew. Workers were hired for shorter times, sometimes just a week, and only paid in cash. By 1830, farm laborers had lost most of their old rights, except for help from the parish under the Old Poor Law.

Historically, monasteries helped the poor. After they closed in the 1500s, parishes took over. A law in 1662 said that only people native to a parish could get help there. Landowners paid a tax called a Parish Rate, which helped sick or jobless residents. But the payments were very small and sometimes humiliating. As more people needed help, landowners complained about the costs, and less help was offered. For example, a man in Berkshire needed three loaves of bread a week in 1795, but in Wiltshire in 1817, he only got two. Farmers also paid very low wages, knowing the parish would top up the pay to a basic living level.

On top of this, there was the church tithe. This was the church's right to a tenth of the harvest. The church could reduce this payment, but many tithe-owners refused.

The final problem was the new horse-powered threshing machines. These machines could do the work of many men. They quickly spread and threatened the jobs of thousands of farm workers. After very bad harvests in 1828 and 1829, farm laborers faced the winter of 1830 with great fear.

How the Riots Spread

The riots started in Kent. The Swing Rioters broke threshing machines and threatened farmers who owned them. The protests quickly spread through southern counties like Surrey, Sussex, Middlesex, and Hampshire. Then they moved north into the Home Counties, the Midlands, and East Anglia. At first, people thought the riots were only in the south and East Anglia, but later research showed they were much more widespread, affecting almost every county south of Scotland.

Most of the incidents (60%) happened in the south (Berkshire 165, Hampshire 208, Kent 154, Sussex 145, Wiltshire 208). East Anglia had fewer incidents (Cambridge 17, Norfolk 88, Suffolk 40). The Southwest, Midlands, and North were only slightly affected.

The rioters used different methods in different areas. Often, threatening letters signed by Captain Swing were sent to local officials, church leaders, or rich farmers. These letters demanded higher wages, lower tithe payments, and the destruction of threshing machines. If the warnings were ignored, local farm workers, often in groups of 200 to 400, would gather. They would threaten the local leaders if their demands were not met. Threshing machines would be broken, and workhouses and tithe barns attacked. Then the rioters would leave or move to the next village. Buildings that housed the engines for threshing machines, called gin gangs or wheelhouses, were also destroyed, especially in southeastern England.

Other actions included setting fire to farms, barns, and haystacks at night to avoid being caught. While some actions like arson were secret, meetings with farmers and overseers about their complaints happened during the day.

Even though the rioters used the slogan "Bread or Blood," only one person died during the riots. This was a rioter killed by a soldier or farmer. The rioters mainly wanted to damage property, not hurt people.

The quick spread of the riots was often blamed on outside agitators or "agents" from France. A revolution had happened in France in July 1830, just before the Swing Riots began in Kent.

Despite all the different tactics, the farm workers' main goals were simple: to get a basic living wage and to end unemployment in the countryside.

A 2021 study found that news about the riots spread through personal and trade networks, not through transport or mass media. This information was not about stopping the riots, and local organizers were important in spreading the protests.

What Happened After the Riots?

Eventually, some farmers agreed to raise wages, and some church leaders and landlords reduced tithes and rents. However, many farmers did not keep their promises, and the unrest grew.

Many people believed that political reform was the only way to solve the problems. One such person was the writer William Cobbett. He was charged with writing articles that encouraged rebellion because of his writings in the Political Register about the Swing Riots. He wrote an article called The Rural War, blaming those who lived off unearned money while farm laborers worked hard. His solution was to change Parliament. He was found not guilty, which was embarrassing for the government.

A big worry was that the Swing Riots could lead to a larger rebellion. This fear was made worse by the revolution in France in July 1830, which removed King Charles X, and Belgium becoming independent later that year. Support for changing Parliament was divided by political parties. The Tories were against reform, while the Whigs had suggested changes even before the Swing Riots. The farm laborers involved in the riots could not vote. However, it is likely that the landowners, who could vote, were influenced by the riots to support reform.

Earl Grey, a leader in the House of Lords, said in November 1830 that the best way to stop the violence was to reform the House of Commons. The Tory Prime Minister, the Duke of Wellington, disagreed. He said the current system was perfect. When this was reported, a crowd attacked Wellington's home in London. The unrest had been mostly in Kent, but in the next two weeks of November, it spread quickly into Sussex and Hampshire, with Swing letters appearing in other nearby counties.

On November 15, 1830, Wellington's government lost a vote in the House of Commons. Two days later, Earl Grey was asked to form a new Whig government. Grey created a committee to plan parliamentary reform. Lord Melbourne became the Home Secretary. He thought local judges were too soft. The government then sent a special group of three judges to try rioters in Berkshire, Buckinghamshire, Dorset, Wiltshire, and Hampshire.

The landowners felt very threatened by the riots and reacted with harsh punishments. Nearly 2,000 protesters were put on trial in 1830–1831. Of these, 252 were sentenced to death (but only 19 were actually hanged). 644 were sent to prison, and 481 were sent to Australia. Not all rioters were farm workers; the list of those punished included shoemakers, carpenters, blacksmiths, and other village craftspeople. Many of those sent to Australia had their sentences canceled in 1835.

The riots greatly influenced the Whig government. They added to the social and political unrest in Britain in the 1830s. This led to a bigger demand for political reform, resulting in the Great Reform Act, 1832. This act was the first of many changes that, over a century, transformed the British political system. It moved from a system based on privilege to one based on everyone being able to vote and secret ballots. Before the Great Reform Act of 1832, only about three percent of the English population could vote. Most voting areas were very old, so new industrial areas in the north had almost no representation. Those who could vote were mainly large landowners and rich commoners.

The Great Reform Act was followed by the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834. This law stopped giving cash or goods to the poor outside of workhouses. Instead, it set up a system of unpleasant workhouses across the country where the poor had to go if they wanted help.

See also

- British Agricultural Revolution

- Ely and Littleport riots of 1816

- Luddite

- Rebecca Riots

- Tolpuddle Martyrs

- William Winterbourne

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |