English Poor Laws facts for kids

The English Poor Laws were a system in England and Wales that aimed to help people who were poor or couldn't work. This system started a long time ago, around the late 1500s, and continued until after the Second World War when modern social support systems were created.

The history of the Poor Laws is usually split into two main parts. The first part is called the Old Poor Law, which began during the time of Elizabeth I (1558–1603). The second part is the New Poor Law, passed in 1834. This new law changed the system a lot. Before, help for the poor was managed differently in each local area. The New Poor Law made it more organized and led to many workhouses being built.

The Poor Law system started to fade away in the early 1900s. This was because new laws were introduced, like the Liberal welfare reforms, and people could get help from other groups like friendly societies and trade unions. The Poor Law system was officially ended in 1948 with the National Assistance Act 1948.

Contents

How the Poor Laws Developed

Early Poor Laws in Medieval Times

The very first laws about helping the poor came out in the Middle Ages. One of the earliest was the Ordinance of Labourers in 1349, made by King Edward III of England. This law came after the terrible Black Death in England (1348–1350), which killed many people. Because so many workers had died, the people who survived were in high demand. Farmers had to pay more to get workers, which made prices go up.

The new law tried to stop wages from rising and keep food prices low. It said that everyone who could work, must work. It also tried to stop workers from leaving their jobs to find better pay. Later, in 1388, the Statute of Cambridge was passed. This law made it harder for workers and beggars to move around freely.

Tudor Poor Laws: A New Approach

The English Poor Law system really started to take shape during the Tudor period. Before this time, monasteries were the main places that helped the poor. But when King Henry VIII closed the monasteries, this help stopped. So, helping the poor changed from being a choice to being a required tax collected in each local area.

Early laws focused on people who wandered around without a home (called vagrants) and making sure people who could work, did work. This was especially important after the Black Death, when there weren't enough workers.

King Henry VII of England tried to deal with poverty in 1495 with the Vagabonds and Beggars Act 1495. This law said that "vagabonds" (people who wandered without work) should be put in the stocks for three days with only bread and water. Then they had to leave town. It also said that beggars who could work should go back to where they used to live or were born. This law didn't solve poverty, it just moved the problem around. It also didn't separate people who couldn't find work from those who chose not to work; both were called "sturdy beggars" and punished.

In 1530, King Henry VIII of England said that being idle (not working) was the "root of all vices." He ordered that vagabonds should be whipped instead of put in the stocks. A healthy beggar was whipped and told to go back to their hometown to find work. But there was still no help for healthy people who simply couldn't find a job.

In London, there were many poor people. To help them, King Henry VIII allowed St. Bartholomew's Hospital and St. Thomas' Hospital to reopen, but London citizens had to pay for them. Since voluntary donations weren't enough, London started the first required "Poor Rate" tax in 1547. In 1555, London opened the first House of Correction at Bridewell Palace. This was a place where poor people could get shelter and work.

Life became even harder for the able-bodied poor during the reign of Edward VI of England. The Vagabonds Act 1547 said that vagrants could be forced to work for two years and branded with a "V" (for vagrant) for a first offense. A second offense could even lead to death. However, local judges often didn't use these harsh punishments. In 1552, Edward VI passed the Poor Act 1552, which created "Collectors of Alms" in each parish and a list of poor people who were allowed to beg. After this, begging was completely banned.

The government of Elizabeth I of England also had strict laws. An Act in 1572 said that repeat beggars could be hanged. But this Act also made an important difference between "professional beggars" and people who were unemployed through no fault of their own. Elizabeth I also passed laws to directly help the poor. For example, in 1563, her Act for the Relief of the Poor said that all parish residents who could afford it must contribute to collections for the poor. If they refused, they could be fined. The Poor Act 1575 required towns to provide materials like wool or iron for the poor to work with. It also set up houses of correction for those who refused to work.

The most complete set of poor relief laws was made in the Act for the Relief of the Poor 1597 and the Act for the Relief of the Poor 1601. These laws helped the "deserving poor" (those who couldn't work due to age or illness). These laws were created because England was facing economic problems like rising prices and more people in poverty. Also, charitable giving had decreased after the monasteries were closed.

The Old Poor Law System

The Elizabethan Poor Law of 1601 is often seen as the start of the Old Poor Law system. It made official many earlier ways of helping the poor. This system was managed at the local parish level and paid for by local taxes.

Some elderly people might live in parish alms houses, which were usually private charities. Able-bodied beggars who refused to work were often sent to Houses of Correction or even beaten. It was not common for many able-bodied poor people to live in workhouses at this time; most workhouses were built later. The 1601 Law also said that parents and children were responsible for each other, meaning elderly parents would live with their children.

The Old Poor Law was based in parishes, which were small local areas around a church. There were about 15,000 parishes. This system allowed local officials to decide who deserved help. Because these officials knew the people in their area, they could tell the difference between those who truly needed help and those who were just lazy. This made the system more fair and effective at first. The 1601 Law worked well when the population was small and everyone knew each other. But by 1750, it needed to change because the population was growing, people were moving more, and prices varied across regions.

The 1601 Act aimed to help "settled" poor people who were temporarily out of work. They were expected to accept help either inside a workhouse (indoor relief) or outside (outdoor relief). At this time, neither type of help was seen as harsh. The law also aimed to control beggars, who were seen as a threat to public order. It was believed that the fear of poverty made people work. In 1607, a House of Correction was set up in each county.

However, the system varied a lot, and poor people often moved to parishes that offered more help, usually in towns. This led to the Poor Relief Act 1662, also known as the Settlement Act. This law said that people could only get help if they were established residents of a parish, usually by birth, marriage, or apprenticeship. This law made it harder for workers to move and discouraged poor people from leaving their parish to find work. It also encouraged employers to offer short contracts so workers couldn't become eligible for poor relief.

A poor person applying for help had to prove they had a "settlement." If they couldn't, they were sent back to the parish closest to their birthplace or where they had some connection. Some poor people were moved hundreds of miles. In 1697, a law required beggars to wear a red or blue cloth "badge" with a letter "P" (for pauper) and the initial of their parish. But this practice soon stopped.

Workhouses started to become more common in the late 1600s. The Bristol Corporation of the Poor was set up in 1696 and created a workhouse that combined housing for the poor with a place for minor offenders. Other towns followed Bristol's example.

In 1723, the Workhouse Test Act was passed. This law allowed single parishes or groups of parishes to set up their own workhouses. By 1776, there were about 1,912 workhouses in England and Wales, housing almost 100,000 poor people. By the end of the century, about one million people were getting some kind of help from the parish. Even though many people hoped to make money from the work of the poor in workhouses, most people living there were sick, elderly, or children, and their work didn't make much profit. Workhouses often became places that served many purposes, like nurseries, shelters, hospitals for the elderly, and orphanages.

In 1782, Thomas Gilbert helped pass an Act that created poor houses just for the aged and sick. It also brought back outdoor relief (help given outside a workhouse) for able-bodied people. This led to the Speenhamland system, which gave money to low-paid workers. The Settlement Laws were changed in 1795, so people couldn't be moved unless they had actually asked for help.

During the Napoleonic Wars, it was hard to bring cheap grain into Britain, which made the price of bread go up. Wages didn't increase, so many farm workers became very poor. After the wars ended in 1814, the government passed the Corn Laws to keep grain prices high. The years after 1815 saw a lot of social unrest, with high unemployment. People's ideas about poverty began to change, and many thought the Poor Law system needed a big change. The system was criticized for getting in the way of the "free market." By 1820, before the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834 was passed, more workhouses were being built to try and lower the rising costs of poor relief.

The Royal Commission on the Poor Law

In 1832, a special group called the 1832 Royal Commission into the Operation of the Poor Laws was set up. This happened after a lot of destruction and machine-breaking during the Swing Riots. The group, which included Nassau William Senior and Edwin Chadwick, looked into how the Poor Laws were working.

The Commission was worried that the Old Poor Law system was making it harder for independent workers to find jobs. They were especially concerned about two practices: the "roundsman" system, where poor people were hired out as cheap labor, and the Speenhamland system, which gave money to workers with low wages. The report concluded that the existing Poor Laws were hurting the country's economy by interfering with how supply and demand naturally work. It also said that the current system allowed employers to pay lower wages.

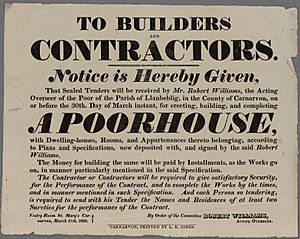

The report suggested that there should be separate workhouses for different groups: the elderly, the sick, children, able-bodied women, and able-bodied men. It also said that parishes should be grouped together into "unions" to share the cost of workhouses. A central authority should be created to make sure these rules were followed. The Poor Law Commission wrote its report in a year, and its ideas were easily passed by Parliament in 1834.

The New Poor Law System

The Poor Law Amendment Act was passed in 1834. This law largely put into action the ideas from the Royal Commission. The New Poor Law was a huge change and is seen as one of the most important laws of the 1800s. It aimed to reduce the cost for taxpayers. Even though it was called an "amendment act," it completely changed the old system. It set up a Poor Law Commission to manage the system across the country. This included combining small parishes into poor law unions and building workhouses in each union to provide help. The system was still paid for by a "poor rate" tax on property owners.

The Poor Law Amendment Act said that no able-bodied person could receive money or other help from the Poor Law authorities unless they went into a workhouse. Conditions in workhouses were meant to be harsh to discourage people from asking for help. Workhouses were to be built in every parish, or parishes could join together to form unions. The Poor Law Commissioners were in charge of making sure the Act was followed.

However, some parts of the Act were hard to enforce. Making workhouse conditions too harsh could mean starving people, which wasn't allowed. Also, building workhouses was very expensive for taxpayers, so outdoor relief (help outside the workhouse) continued to be a popular choice because it was cheaper. The Outdoor Labour Test Order and Outdoor Relief Prohibitory Order were issued to try and stop people from getting help outside the workhouse.

When the new law was applied to the industrial North of England, it didn't work well. Many people there were temporarily unemployed because of economic problems. They didn't want to go into a workhouse, even though it was the only way to get help.

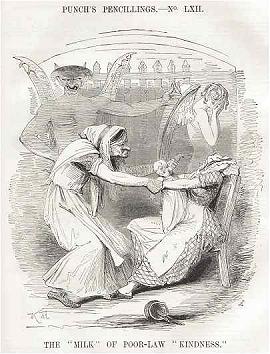

Writers like Charles Dickens and Frances Trollope wrote about the problems and harshness of the workhouse system. The goal was to make life in the workhouse worse than life outside, but it was hard to do without starving people. So, other ways were found to discourage people, like making them wear prison-style uniforms and separating people into different yards (men, women, boys, girls).

In 1846, the Andover workhouse scandal showed that conditions in the Andover workhouse were very bad. This led to a government review and the Poor Law Commission being replaced by a Poor Law Board. This meant that a committee of Parliament, led by a cabinet minister, would manage the Poor Law. Despite this, another scandal happened in the Huddersfield workhouse due to inhumane treatment.

After the New Poor Law

After 1847, the Poor Law Commission was replaced by a Poor Law Board. This change happened because of the Andover workhouse scandal and disagreements among the commissioners. The Workhouse Visiting Society, formed in 1858, brought attention to workhouse conditions, leading to more inspections. The Union Chargeability Act 1865 made the cost of helping the poor shared by entire unions, not just individual parishes. Most local officials were middle-class and wanted to keep poor rates low.

After 1867, more welfare laws were passed. As these laws needed local support, the Poor Law Board was replaced by a Local Government Board in 1871. This new board tried to reduce outdoor relief, believing it made poor people less self-reliant. This effort reduced the number of people claiming outdoor relief by a third and increased the number of people in workhouses. Over time, the Poor Law policy for the elderly, the sick, the mentally ill, and children became more humane. This was partly because it was expensive to have "mixed workhouses" (housing all these groups together) and because ideas about poverty were changing.

The End of the Poor Law System

The Poor Law system began to decline as other forms of help became available. Friendly societies and some trade unions offered support to their members. In 1885, a law meant that people who received medical care paid for by the poor rate could still vote. In 1886, the government encouraged local boards to set up work projects during high unemployment instead of using workhouses. In 1905, the Conservatives passed a law that provided temporary jobs for unemployed workers.

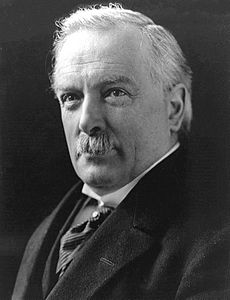

In 1905, a Royal Commission was set up to suggest changes to the Poor Law. The Liberal government largely ignored their reports when they introduced their own Liberal welfare reforms. These reforms provided social services without the shame of the Poor Law, including Old age pensions and National Insurance. From 1911, the term "Workhouse" was changed to "Poor Law Institution".

During the First World War, some workhouses were used as makeshift hospitals for wounded soldiers. The number of people using the Poor Law system increased between 1921 and 1938, even though unemployment insurance was extended to most workers. Many of these people received outdoor relief. A big problem was that the cost of helping the poor was not shared equally; poorer areas had to pay more. This was a key issue in the Poplar Rates Rebellion in 1921.

The poverty during the years between the two World Wars (1918–1939) led to several actions that largely ended the Poor Law system. Workhouses were officially abolished by the Local Government Act 1929. Between 1929 and 1930, the "workhouse test" and the term "pauper" disappeared. The Unemployment Assistance Board was set up in 1934 to help those not covered by earlier insurance acts. By 1937, able-bodied poor people were helped by this new scheme. By 1936, only a small number of people were still receiving poor relief in institutions.

In 1948, the Poor Law system was finally abolished with the creation of the modern welfare state and the passing of the National Assistance Act. The National Health Service Act 1946 also came into force in 1948, creating the National Health Service we know today.

Opposition to the Poor Laws

Opposition to the Poor Law grew in the early 1800s. The 1601 system was seen as too expensive and was thought to encourage poverty. Thinkers like Jeremy Bentham believed in a strict, punishing approach to social problems. Thomas Malthus worried about too many people and the rise of children born outside marriage.

After the Napoleonic Wars, some reformers changed the idea of the "poorhouse" into a "deterrent workhouse" – a place so unpleasant that people would avoid it. The first of these was in Bingham, Nottinghamshire. Another famous one was Becher's workhouse in Southwell.

The introduction of the New Poor Law also faced strong opposition. Some people argued that the old system was good enough and could adapt to local needs. This argument was especially strong in the industrial North of England, where outdoor relief was a better and cheaper way to deal with temporary unemployment. Poor Law commissioners faced the most resistance in Lancashire and West Riding of Yorkshire in 1837, during a time of high unemployment. People in these areas saw the New Poor Law as interference from Londoners who didn't understand local issues.

The movement against the New Poor Law was short-lived, and many people who opposed it later joined the Chartism movement, which fought for workers' rights.

See also

- Social welfare, government programs that seek to provide a minimum level of income, service or other support for certain people

- Timeline of the Poor Law system

- Welfare (financial aid)

- Social care in the United Kingdom

Images for kids

-

Although many deterrent workhouses developed in the period after the New Poor Law, some had already been built under the existing system. This workhouse in Nantwich, Cheshire, dates from 1780.

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |