G. K. Chesterton facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

G. K. Chesterton

KC*SG

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 29 May 1874 Kensington, London, England |

| Died | 14 June 1936 (aged 62) Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire, England |

| Resting place | Roman Catholic Cemetery, Beaconsfield |

| Occupation |

|

| Education | St Paul's School |

| Alma mater | University College London |

| Period | 1900–1936 |

| Genre | Essays, fantasy, Christian apologetics, Catholic apologetics, mystery, poetry |

| Literary movement | Catholic literary revival |

| Notable works |

|

| Spouse |

Frances Blogg

(m. 1901) |

| Relatives |

|

| Signature | |

|

|

Gilbert Keith Chesterton (born May 29, 1874 – died June 14, 1936) was a famous English writer and thinker. He was known for his essays, novels, and poems. People sometimes called him the "prince of paradox" because he liked to turn common ideas upside down to make a point. He was also a Christian apologist, which means he wrote to defend the Christian faith.

Chesterton created the popular detective character Father Brown, a clever priest who solves mysteries. Many people, even those who didn't agree with him, enjoyed his books like Orthodoxy and The Everlasting Man. Chesterton saw himself as an orthodox Christian. He later became a Roman Catholic after being an Anglican.

About G. K. Chesterton

His Early Life

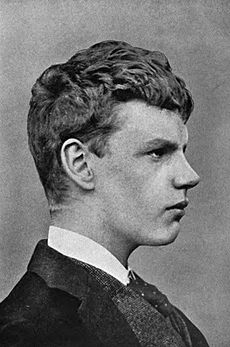

Gilbert Keith Chesterton was born in Kensington, London. His father, Edward Chesterton, was an estate agent. His mother was Marie Louise. He was baptized into the Church of England as a baby.

As a young man, Chesterton became interested in the occult. He even experimented with Ouija boards with his brother, Cecil. He went to St Paul's School. Then he studied art at the Slade School of Art to become an illustrator. He also took literature classes at University College London but did not finish a degree.

In 1901, he married Frances Blogg. Their marriage lasted his whole life. Chesterton said Frances helped him return to the Anglican faith. Later, he joined the Roman Catholic Church in 1922. They did not have children.

One of his school friends was Edmund Clerihew Bentley. Bentley invented the clerihew, which is a short, funny poem about a person. Chesterton wrote clerihews too. He also drew pictures for Bentley's first book of poems.

Becoming a Writer

In 1895, Chesterton started working for a publisher in London. He then moved to another publishing house in 1896. During this time, he also began working as a freelance writer. He wrote about art and books.

In 1902, the Daily News newspaper gave him a weekly column. Then, in 1905, he started writing a weekly column for The Illustrated London News. He wrote for them for the next thirty years.

Chesterton was very good at art and wanted to be an artist. His writing often used vivid pictures to explain ideas. Even his stories had hidden lessons. For example, his character Father Brown often helps criminals understand their mistakes. He encourages them to change their ways.

His Famous Debates

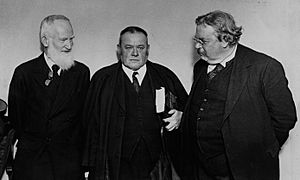

Chesterton loved to debate and discuss ideas with others. He often had friendly public arguments with famous people. These included George Bernard Shaw, H. G. Wells, and Bertrand Russell. He even said that he and Shaw acted like cowboys in a silent movie that was never released!

Chesterton was a very tall and large man. He was about 6 feet 4 inches (1.93 m) tall and weighed around 20 stone 6 pounds (130 kg; 286 lb). There are many funny stories about his size. During World War I, a lady asked him why he wasn't fighting at the front. He replied, "If you go round to the side, you will see that I am."

He often wore a cape and a crumpled hat. He also carried a swordstick and had a cigar in his mouth. He was known for forgetting where he was going. He would sometimes miss his train. It is said that he would send telegrams to his wife, Frances, asking, "Am in Market Harborough. Where ought I to be?"

In 1931, the BBC asked Chesterton to give radio talks. He started slowly but soon gave over 40 talks a year. He was allowed to speak freely, which made his talks feel very personal. His talks became very popular. A BBC official said he would have become a dominant voice on the radio. Chesterton was even nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1935.

Chesterton was also a member of the Detection Club. This was a group of British mystery writers. He was their first president from 1930 to 1936.

His Later Years and Legacy

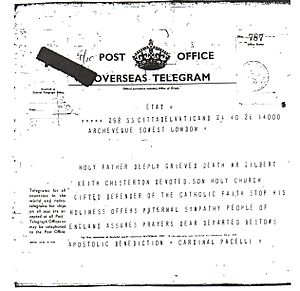

Chesterton died on June 14, 1936, at age 62. He passed away at his home in Beaconsfield, England. His last words were a greeting to his wife. He is buried in the Catholic Cemetery in Beaconsfield.

Near the end of his life, Pope Pius XI honored him. He made Chesterton a Knight Commander with Star of the Papal Order of St. Gregory the Great. Some people have suggested that he should be made a saint.

Chesterton's Writings

Chesterton wrote a lot! He wrote about 80 books, hundreds of poems, and thousands of essays. He also wrote short stories and plays. He was a literary critic, historian, and a Catholic theologian. He wrote for newspapers like the Daily News and The Illustrated London News. He even had his own paper called G. K.'s Weekly.

His most famous character is the priest-detective Father Brown. Father Brown appeared in many short stories. His novel The Man Who Was Thursday is also very well-known. Chesterton was a strong Christian before he became Catholic. Christian ideas and symbols appear in much of his work.

One of his non-fiction books, Charles Dickens: A Critical Study (1906), was highly praised. This book helped bring back interest in the works of Charles Dickens. It also made scholars look at Dickens's work more seriously.

Chesterton's writing was always full of wit and humor. He used paradox to make serious points about the world. He wrote about government, politics, economics, and philosophy.

The famous poet T.S. Eliot said that Chesterton was "importantly and consistently on the side of the angels." He meant that Chesterton always supported good and important ideas. Eliot also said that Chesterton's book on Charles Dickens was the best essay ever written about that author.

His Ideas and Friends

His Views on Life

In his book Heretics, Chesterton wrote about Oscar Wilde. He said that Wilde's ideas about enjoying life were not for happy people. Instead, they were for very unhappy people. Chesterton believed that true joy looks for something lasting, not just temporary pleasures.

Chesterton and George Bernard Shaw were famous friends. They loved to argue and discuss things. Even though they rarely agreed, they respected each other. Chesterton clearly explained their differences in his writings.

Shaw represented new ways of thinking, called modernism. Chesterton's views, however, became more focused on the Church. Chesterton believed that some modern thinkers were very smart but said things that didn't make sense. He called his way of thinking "Uncommon Sense."

Chesterton also had strong political ideas. He criticized both progressivism (wanting constant change) and conservatism (wanting to keep things the same). He said, "The whole modern world has divided itself into Conservatives and Progressives. The business of Progressives is to go on making mistakes. The business of the Conservatives is to prevent the mistakes from being corrected." He was briefly part of the Fabian Society, a socialist group, but left during the Boer War.

A writer named James Parker said that Chesterton was hard to define. He was a Catholic writer, a cultural figure, and a very productive author. He wrote poetry, criticism, fiction, and biographies. Parker called him a "genius" whose writing was "supremely entertaining."

Supporting Catholicism

Chesterton's book The Everlasting Man helped C. S. Lewis become a Christian. Lewis called it "the best popular apologetic I know." This means it was a great book for explaining and defending Christianity to a wide audience.

Chesterton also wrote a hymn called "O God of Earth and Altar." It was included in the English Hymnal in 1906. Parts of this hymn were even used in a song by the heavy metal band Iron Maiden!

Étienne Gilson, a famous philosopher, praised Chesterton's book about St Thomas Aquinas. He said it was "the best book ever written on Saint Thomas." He felt that Chesterton's cleverness put his own deep knowledge to shame.

Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen, another famous writer, said Chesterton had the biggest impact on his own writing style. He admired how Chesterton used paradox and avoided boring language.

Accusations of Antisemitism

Chesterton faced accusations of antisemitism (prejudice against Jewish people) during his lifetime. He wrote in his 1920 book The New Jerusalem that this was something "for which my friends and I were for a long period rebuked and even reviled."

Historians have discussed his views. Some of his fictional works included caricatures of Jewish people that used common stereotypes. However, Chesterton also wrote against the idea of racial superiority. He criticized the pseudo-scientific race theories that were becoming popular. He believed that the idea of a "Chosen Race" was dangerous.

Chesterton strongly opposed Hitler's rule as soon as it began. He wrote against German race theories, saying that "the essence of Nazi Nationalism is to preserve the purity of a race in a continent where all races are impure."

Some scholars argue that Chesterton's views were complex. They point out that he defended Jewish people from Nazism. He also supported Zionism, the idea of a Jewish homeland. Ann Farmer, an author, says that Chesterton was a "defender of Jews in his youth" and "returned to the defence when the Jewish people needed it most."

Chesterton's Fence

'Chesterton's fence' is a famous idea from his writings. It means that you should not change something until you understand why it was put there in the first place. It's like a fence: don't tear it down until you know why it was built.

"Chesterbelloc"

Chesterton was very close friends with the poet and essayist Hilaire Belloc. George Bernard Shaw jokingly called their partnership "Chesterbelloc." Even though they were different, they shared many beliefs. In 1922, Chesterton joined Belloc in the Catholic faith. Both of them criticized both capitalism and socialism. Instead, they supported a different idea called distributism. This idea suggests that property should be spread out among many people, not just a few.

Belloc wrote that Chesterton was excellent at writing about famous English writers. He could sum up a writer's style in just a few sentences.

Chesterton's Influence

In Literature

Chesterton's ideas influenced many people. His system of Distributism affected the sculptor Eric Gill. Gill started a group of Catholic artists who lived together and shared Chesterton's ideas.

Chesterton's novel The Man Who Was Thursday inspired Michael Collins, an Irish leader. Collins loved Chesterton's book The Napoleon of Notting Hill.

Chesterton's newspaper column in 1909 had a big effect on Mahatma Gandhi. Gandhi was so impressed that he had it reprinted in his own newspaper.

Another person influenced by Chesterton was Marshall McLuhan, a Canadian media expert. He said Chesterton's book What's Wrong with the World changed his life.

The author Neil Gaiman grew up reading Chesterton. He said The Napoleon of Notting Hill influenced his own book Neverwhere. Gaiman even based a character in his comic book The Sandman on Chesterton. His novel Good Omens, written with Terry Pratchett, is dedicated to Chesterton.

The Argentine author Jorge Luis Borges also said Chesterton influenced his fiction. He noted that Chesterton "knew how to make the most of a detective story."

In Education

Chesterton's ideas about education have inspired many educators. The Chesterton Schools Network, which includes the Chesterton Academy, uses his principles. Christopher Perrin, an educator, often refers to Chesterton in his work with classical schools.

Namesakes

In 1974, Father Ian Boyd started The Chesterton Review. This is a scholarly journal about Chesterton and his friends.

In 1996, Dale Ahlquist founded the American Chesterton Society. This group works to explore and promote Chesterton's writings.

In 2008, a Catholic high school called Chesterton Academy opened in the Minneapolis area. Another school, Scuola Libera Chesterton, opened in Italy that same year.

In 2012, a crater on the planet Mercury was named Chesterton after him.

In 2014, G.K. Chesterton Academy of Chicago, a Catholic high school, opened in Highland Park, Illinois.

Chesterton is also a character in some books. He is the main character in the Young Chesterton Chronicles, a series of young adult adventure novels. He also appears in the G K Chesterton Mystery series of detective novels.

Major Works

Books

- The Napoleon of Notting Hill (1904)

- Orthodoxy (1908)

- The Man Who Was Thursday (1908)

- What's Wrong with the World (1910)

- Father Brown stories (detective fiction)

- The Everlasting Man (1925)

- The New Jerusalem (1920)

- Charles Dickens: A Critical Study (1906)

- Heretics (1905)

- St. Thomas Aquinas (1933)

Short Stories

- "The Trees of Pride", 1922

- "The Crime of the Communist", Collier's Weekly, July 1934.

- "The Three Horsemen", Collier's Weekly, April 1935.

- "The Ring of the Lovers", Collier's Weekly, April 1935.

- "A Tall Story", Collier's Weekly, April 1935.

- "The Angry Street – A Bad Dream", Famous Fantastic Mysteries, February 1947.

Plays

- Magic, 1913.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: G. K. Chesterton para niños

In Spanish: G. K. Chesterton para niños

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |