George Bernard Shaw facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

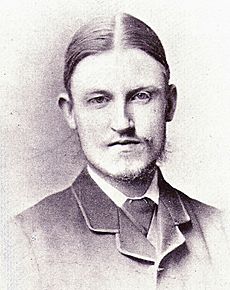

George Bernard Shaw

|

|

|---|---|

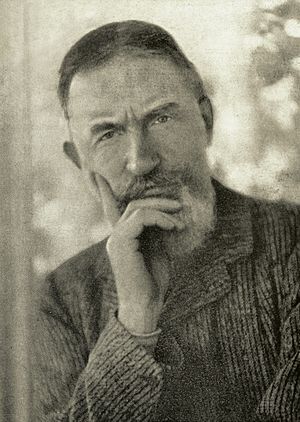

Shaw in 1911, by Alvin Langdon Coburn

|

|

| Born | 26 July 1856 Portobello, Dublin, Ireland |

| Died | 2 November 1950 (aged 94) Ayot St Lawrence, Hertfordshire, England |

| Resting place | Shaw's Corner, Ayot St Lawrence |

| Occupation |

|

| Citizenship | British (1856–1950) Irish (dual citizenship, 1934–1950) |

| Spouse |

Charlotte Payne-Townshend

(m. 1898; died 1943) |

| Signature | |

George Bernard Shaw (born July 26, 1856 – died November 2, 1950) was a famous Irish writer. He was known as Bernard Shaw. He wrote many plays, worked as a critic, and was involved in politics. His ideas and plays were very important in theater, culture, and politics from the 1880s until he died and even after.

Shaw wrote over sixty plays. Some of his most famous works include Man and Superman (1902), Pygmalion (1913), and Saint Joan (1923). His plays often used humor to talk about serious topics like society and history. He became the most important playwright of his time. In 1925, he won the Nobel Prize in Literature for his amazing writing.

Born in Dublin, Ireland, Shaw moved to London in 1876. He worked hard to become a writer and taught himself a lot. By the mid-1880s, he was a respected critic of theater and music. He became interested in politics and joined a group called the Fabian Society. This group believed in making changes to society slowly. Shaw used his plays to share his ideas about politics, society, and religion. By the early 1900s, he was a very well-known playwright. His successful plays included Major Barbara, The Doctor's Dilemma, and Caesar and Cleopatra.

Shaw sometimes had strong opinions that were not popular. For example, he spoke out against both sides in World War I. Even though he was not an Irish republican, he criticized British policies in Ireland after the war. These opinions did not stop him from writing. In the years between the two World Wars, he wrote many important plays. In 1938, he wrote the movie script for Pygmalion. For this, he won an Academy Award. He continued to write until he was very old. He died at ninety-four, having turned down many honors from the government.

After Shaw's death, people have continued to study and discuss his works. Many experts believe he is the second most important British playwright after Shakespeare. He greatly influenced many English-speaking playwrights. The word Shavian is now used to describe ideas and ways of speaking that are like Shaw's.

Contents

Life Story of George Bernard Shaw

Early Life in Dublin

George Bernard Shaw was born in Dublin, Ireland, on July 26, 1856. He was the youngest of three children. His family was of English background and part of the Protestant ruling class in Ireland. His father, George Carr Shaw, had a government job but later worked as a corn merchant. His mother, Lucinda Elizabeth Shaw, was a talented singer.

Shaw's mother became close to George John Lee, a music teacher and conductor. Shaw later wondered if Lee might have been his real father. Shaw felt his mother was not very loving, but he found comfort in music. Their home was often filled with music, with many singers and musicians visiting.

In 1862, Shaw's family and Lee shared a house in Dublin and a country cottage. Shaw, a sensitive boy, preferred the cottage. Lee's students often gave him books, which Shaw loved to read. This helped him learn a lot about music and literature.

Shaw went to four different schools between 1865 and 1871. He disliked all of them. He later said that schools were like "prisons." In October 1871, he left school to work as a clerk in a land agency in Dublin. He worked hard and quickly became the head cashier. During this time, he was known as "George Shaw." After 1876, he preferred to be called "Bernard Shaw."

In 1873, Lee moved to London, and Shaw's mother and sisters followed him. Shaw stayed in Dublin with his father. He missed the music in the house and taught himself to play the piano.

Moving to London

In early 1876, Shaw learned that his sister Agnes was dying. He quit his job and moved to England in March to be with his mother and sister Lucy for Agnes's funeral. He never lived in Ireland again and did not visit for 29 years.

At first, Shaw did not want to work in an office in London. His mother let him live with her for free. He spent most weekdays at the British Museum Reading Room, reading and writing. His first attempt at writing a play in 1878 was not finished. His first completed novel, Immaturity (1879), was not published until the 1930s. He worked briefly for the Edison Telephone Company in 1879–80. He was promoted quickly, but when the company merged with another, he decided to become a full-time writer.

For the next four years, Shaw earned very little from writing. His mother supported him. In 1881, he became a vegetarian. He grew a beard to hide a scar from smallpox. He wrote two more novels, The Irrational Knot (1880) and Love Among the Artists (1881), but they were not published as books until later.

In 1880, Shaw started going to meetings of the Zetetical Society, which aimed to "search for truth." There he met Sidney Webb, who also loved learning. They became lifelong friends. Shaw said they learned a lot from each other because they knew different things.

In 1884, a critic named William Archer suggested they write a play together. The idea didn't work out, but Shaw later used it for his play Widowers' Houses in 1892. Archer's friendship was very helpful for Shaw's career.

Political Ideas and the Fabian Society

On September 5, 1882, Shaw heard a speech by economist Henry George. This made him very interested in economics. He started reading about Karl Marx and his ideas. Shaw joined the Fabian Society in September 1884. This group believed in making social changes slowly and peacefully. Shaw quickly became an important writer for the society.

Shaw's political ideas changed over time. He moved away from Marx's ideas and believed in making changes step-by-step. He thought that socialism could be achieved through democratic means. In 1889, the Fabian Society published Fabian Essays in Socialism, which Shaw edited and contributed to. This book helped make the society more well-known.

Becoming a Novelist and Critic

The mid-1880s were a turning point for Shaw. He had two novels published and started working as a critic. He wrote book and music reviews for London newspapers. He admired the ideas of William Morris and John Ruskin, who believed that art should teach moral lessons. Shaw agreed, thinking that all great art should teach something.

Shaw became very well known as a music critic. He wrote for The Star and The World. His music reviews were praised for their excellent writing. He stopped being a full-time music critic in 1894 but continued to write about music occasionally.

From 1895 to 1898, Shaw was the theater critic for The Saturday Review. He wrote under the name "G.B.S." He criticized the old-fashioned plays of the time and called for new plays with real ideas and characters. By this time, he was also seriously working on his own plays.

Playwright and Politician: 1890s

Shaw continued writing plays after Widowers' Houses was performed in 1892.

His first play to bring him financial success was Arms and the Man (1894). This comedy made fun of ideas about love, military honor, and social classes. Some critics didn't like it, but the public loved it. It earned him enough money to quit his job as a music critic.

Other plays like Candida (1895) and The Man of Destiny (1897) were not as successful at first. However, his historical play The Devil's Disciple was a big hit in New York in 1897, earning him a lot of money.

In 1893, Shaw attended a conference that led to the creation of the Independent Labour Party. He helped shape some of their early ideas. In 1895, the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) was opened, partly thanks to money from a Fabian Society supporter. Shaw was initially against the idea but later supported it.

By the late 1890s, Shaw focused more on writing plays. In 1897, he became a local councilor in London. He took his duties seriously.

In 1898, Shaw became ill from overwork. He was cared for by Charlotte Payne-Townshend, a wealthy Irish woman he knew. She had proposed marriage to him the year before, and he had said no. But when she insisted on nursing him, he agreed to marry her to avoid scandal. They married on June 1, 1898. Both were 41 years old. Their marriage was very happy, and they had no children. In 1906, the Shaws bought a country home in Ayot St Lawrence, Hertfordshire, which they called "Shaw's Corner". They lived there for the rest of their lives.

Success on Stage: 1900–1914

In the early 1900s, Shaw became a very famous playwright. From 1904 to 1909, a theater company at the Royal Court Theatre staged fourteen of his plays. One of these, John Bull's Other Island, was a comedy about an Englishman in Ireland. Even King Edward VII saw it and laughed so much he broke his chair! Shaw and the Irish poet William Butler Yeats were good friends.

Man and Superman, finished in 1902, was very successful in London and New York. Other popular plays by Shaw included Major Barbara (1905), which looked at different ideas of right and wrong, and The Doctor's Dilemma (1906), about doctors' choices. Caesar and Cleopatra was Shaw's version of the famous story.

Shaw also wrote plays that were more like discussions, such as Getting Married (1908) and Misalliance (1910). One of his plays, The Shewing-Up of Blanco Posnet (1909), was banned in England because of its religious themes, so it was performed in Dublin instead. Fanny's First Play (1911), a comedy about women fighting for the right to vote, had a very long run of 622 performances.

Androcles and the Lion (1912) explored religious ideas. It was followed by one of Shaw's most famous plays, Pygmalion, written in 1912. It was first performed in Vienna and Berlin. Shaw joked that English newspapers always said his plays were dull, so foreign theaters wanted them first. The British production opened in 1914 and was a huge success.

Fabian Years: 1900–1913

When the Second Boer War started in 1899, Shaw wanted the Fabian Society to stay neutral. He thought it was not a "socialist" issue. Others disagreed, and some members left the society.

As the new century began, Shaw felt that the Fabians were not having enough impact on national politics. He did not attend the meeting in 1900 that created the Labour Representation Committee, which later became the Labour Party. By 1903, he had lost his interest in local politics and did not run for re-election. In 1904, he ran for the London County Council but lost. This was his last attempt at elected politics.

Shaw felt the Fabians needed new leaders. He thought the writer H. G. Wells could help, but Wells's ideas clashed with Shaw's. Wells eventually left the society. Shaw remained a member but left the executive committee in 1911.

In 1912, Shaw invested money in a new socialist magazine called The New Statesman. He became a director and contributor. However, he soon disagreed with the editor, who sometimes refused to publish his articles.

First World War and Ireland

When World War I began in August 1914, Shaw wrote an article called Common Sense About the War. He argued that all the countries involved were equally to blame. This view was very unpopular when people were feeling very patriotic. Many of his friends were upset with him.

Despite his unpopular opinions, the British government recognized Shaw's writing skills. In 1917, he was invited to visit the battlefields of the Western Front. His report about the soldiers' lives was well-received. In April 1917, he supported America's entry into the war.

Three short plays by Shaw were performed during the war. The Inca of Perusalem (1915) made fun of both the enemy and the British army. O'Flaherty V.C., which criticized the government's view of Irish soldiers, was banned in the UK. Augustus Does His Bit (1917) was a light comedy.

Shaw had always supported Irish Home Rule, meaning Ireland governing itself within the British Empire. In April 1916, he wrote that complete independence for Ireland was not practical. The Easter Rising in Dublin that month surprised him. After the British executed the rebel leaders, Shaw was horrified. He still believed in some form of union between Britain and Ireland.

After the war, Shaw was upset by the British government's harsh policies towards Ireland. He joined other writers in speaking out against them. The Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921 divided Ireland into north and south, which saddened Shaw. In 1922, civil war broke out in the south. Shaw visited Dublin and met Michael Collins, the leader of the new Irish Free State. Shaw was very impressed by Collins and was sad when Collins was killed three days later. Shaw remained a British citizen but also became an Irish citizen in 1934.

The 1920s

Shaw's first major play after the war was Heartbreak House, written in 1916–17 and performed in 1920. Critics thought it was too long, but it had "much entertainment."

Shaw's biggest play was Back to Methuselah, written from 1918–20 and staged in 1922. This series of five plays showed how evolution might work and the effects of living a very long time, from the Garden of Eden to the year 31,920 AD. Critics found the plays uneven. Shaw felt he had used up his creative energy on this huge work and thought he would not write any more plays.

But this feeling did not last long. In 1920, Joan of Arc was made a saint. Shaw had always found Joan interesting. He wrote Saint Joan in 1923. It was a huge success in New York and London. Because of this play, the Nobel Prize committee finally gave Shaw the literature prize in 1925. They praised his work for its "idealism and humanity" and "stimulating satire." He accepted the award but refused the money, saying his readers and audiences gave him enough.

After Saint Joan, Shaw did not write a play for five years. He spent four years writing a political book called The Intelligent Woman's Guide to Socialism and Capitalism, which sold well. He also wrote about the League of Nations, hoping it would become a "Federation of the World."

Shaw returned to theater with The Apple Cart (1928), a political comedy. It was very popular, perhaps because it had some conservative ideas. The play was first performed in Warsaw and then in Britain. Shaw was good friends with the composer Edward Elgar, who was also associated with the Malvern Festival where The Apple Cart premiered.

During the 1920s, Shaw started to lose faith in slow, gradual change. He became interested in strong leaders. In 1922, he welcomed Mussolini coming to power in Italy, seeing him as "the right kind of tyrant."

The 1930s

Shaw's interest in the Soviet Union began in the early 1920s. He called Lenin "the one really interesting statesman in Europe." In 1931, Shaw visited the Soviet Union and met Stalin. Shaw later described Stalin as a "Georgian gentleman" with no meanness in him. He told a gathering there, "I have seen all the 'terrors' and I was terribly pleased by them." In 1933, he signed a letter protesting against unfair reports about the Soviet Union in the British press.

Shaw's admiration for Mussolini and Stalin showed his growing belief that strong leadership was the only way to make things happen. When the Nazi Party came to power in Germany in 1933, Shaw called Hitler "a very remarkable man." He praised Stalin's government throughout the decade.

Shaw's first play of the 1930s was Too True to be Good (1931). Critics found it rambling and tedious.

Shaw traveled a lot with Charlotte during this decade. She loved ocean voyages, and he found peace to write at sea. He visited South Africa in 1932 and was welcomed despite his strong opinions on the country's racial divisions. In 1932, they went on a round-the-world cruise. In 1933, Shaw visited the US for the first time. He had previously called America "that awful country." He visited Hollywood, which he didn't like, and New York, where he gave a lecture. He was glad to leave New York because of the press. He visited New Zealand in 1934 and thought it was "the best country I've been in." He used his time at sea to write two plays, The Simpleton of the Unexpected Isles and The Six of Calais, and started a third, The Millionairess.

Shaw disliked Hollywood but loved cinema. In the mid-1930s, he wrote screenplays for Pygmalion and Saint Joan. Pygmalion was made into a film in 1938. Shaw did not want Hollywood involved, but the film won an Academy Award for "best-written screenplay." He called the award an insult. He was the first person to win both a Nobel Prize and an Oscar.

Shaw's last plays of the 1930s were Cymbeline Refinished (1936), Geneva (1936), and In Good King Charles's Golden Days (1939). Geneva was a satire about European dictators. In Good King Charles's Golden Days was a historical play. None of these plays had long runs in London during his lifetime.

Towards the end of the decade, both Shaws became ill. Charlotte suffered from Paget's disease of bone. Shaw had pernicious anemia, which was treated with injections. This treatment went against his vegetarian beliefs, which upset him.

Second World War and Final Years

Even though Shaw's newer plays were not very popular, his older plays were often performed in London during World War II. Famous actors like John Gielgud and Laurence Olivier starred in them. In 1944, nine of Shaw's plays were staged in London. Two touring companies also performed his plays across Britain. Shaw did not write new plays during this time but focused on journalism. A second film of his work, Major Barbara (1941), was not as successful as Pygmalion.

After the war began in September 1939, Shaw was criticized for saying the war was over and demanding a peace conference. However, when he realized peace was impossible, he publicly urged the United States to join the fight. During the London Blitz (bombing raids), the Shaws, both in their mid-eighties, moved to their country home. In 1943, they moved back to London for Charlotte's medical care. She died in September.

Shaw's last political book, Everybody's Political What's What, was published in 1944. It sold well. After Hitler's death in 1945, Shaw approved of the Irish leader's condolences to the German embassy. Shaw also disagreed with the trials of German leaders after the war, calling them an act of self-righteousness.

A third film of Shaw's work, Caesar and Cleopatra (1945), cost a lot of money and was a big financial failure. Shaw thought the film's lavishness ruined the drama.

In 1946, on his ninetieth birthday, Shaw received honors from Dublin and London. The British government also asked if he would accept the Order of Merit, but he declined. He believed an author's true worth could only be judged after their death.

Shaw continued to write into his nineties. His last plays included Buoyant Billions (1947), Farfetched Fables (1948), a puppet play called Shakes versus Shav (1949), and Why She Would Not (1950), which he wrote shortly before his ninety-fourth birthday.

In his final years, Shaw enjoyed working in his garden. He died at ninety-four after falling while pruning a tree. He was cremated, and his ashes, mixed with Charlotte's, were scattered in their garden.

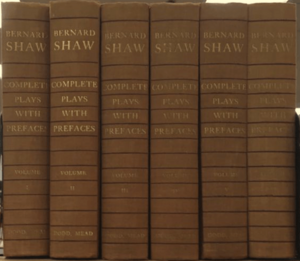

Shaw's Works

Shaw published a collection of his plays in 1934, which included 42 works. He wrote 12 more plays in the last 16 years of his life. In total, he wrote 62 plays.

Plays

Early Plays

Shaw's first three full-length plays were about social problems. He called them "Plays Unpleasant." Widowers' Houses (1892) was about landlords of poor housing.

He then wrote a second group, called "Plays Pleasant." Arms and the Man (1894) was a comedy that used humor to talk about serious ideas like idealism and socialism. Candida (1894) was about a woman choosing between two men. You Never Can Tell (1896) showed how different generations think about society and relationships.

The "Three Plays for Puritans"—The Devil's Disciple (1896), Caesar and Cleopatra (1898), and Captain Brassbound's Conversion (1899)—were all about empires and power. They were set in different times and places.

Plays from 1900–1909

Shaw's main plays in the early 1900s focused on social, political, or ethical issues. Man and Superman (1902) was unique, combining drama with printed text to explain Shaw's ideas about evolution. John Bull's Other Island (1904) humorously showed the relationship between Britain and Ireland. Major Barbara (1905) explored moral questions in an unusual way, comparing arms manufacturers with the Salvation Army. The Doctor's Dilemma (1906) was a serious play about medical ethics.

Getting Married (1908) and Misalliance (1909) were plays where the characters mostly discussed ideas rather than having a lot of action. Shaw also wrote seven short comedies during this time.

Plays from 1910–1919

Between 1910 and the end of World War I, Shaw wrote four full-length plays. Fanny's First Play (1911) looked at middle-class British society. Androcles and the Lion (1912) started as a children's play but became a study of religion. Pygmalion (1912) was about language and its importance in society. Shaw changed the ending to make it clear that the main characters did not end up together romantically. Shaw's only full-length play from the war years was Heartbreak House (1917), which showed Europe heading towards disaster.

His short plays from this time included historical dramas like The Dark Lady of the Sonnets and Great Catherine (1910 and 1913), and satirical works about the war.

Plays from 1920–1950

Saint Joan (1923) was widely praised. Shaw wrote the main role for actress Sybil Thorndike. Shaw's Joan was a strong, sensible mystic. The Apple Cart (1929) was his last big popular success. He called it a "political extravaganza."

Shaw's plays in the 1930s were written during difficult political times. On the Rocks (1933) showed a British prime minister thinking about a dictatorship. The Simpleton of the Unexpected Isles (1934) dealt with ideas about marriage and ended with a "Day of Judgement."

The Millionairess (1934) was a funny play about a successful businesswoman. Geneva (1936) made fun of the weakness of the League of Nations compared to Europe's dictators. In Good King Charles's Golden Days (1939) was a warm, historical comedy. Shaw's later works, though still lively, showed signs of his age. However, they were full of wisdom.

Music and Drama Reviews

Music Reviews

Shaw's collected music reviews fill over 2,700 pages. He wrote for everyone, not just music experts, avoiding difficult technical words. He strongly supported the music of Wagner and criticized composers like Brahms. He also argued against large, amateur choirs in performances.

Drama Reviews

Shaw believed London theaters in the 1890s showed too many old plays and not enough new ones. He fought against "melodrama" and "worn-out conventions." He often compared how different actors performed well-known plays. He wrote over 150 articles as a theater critic. He supported Ibsen's plays when many people found them shocking. Shaw also admired Oscar Wilde, calling him "our only thorough playwright."

Shaw had a complicated view of Shakespeare. He often made fun of people who praised Shakespeare too much without thinking. He also criticized actors and directors who cut Shakespeare's plays badly. However, Shaw was very knowledgeable about Shakespeare. He wrote three plays with Shakespearean themes. Shaw saw Shakespeare's plays from a practical writer's point of view, helping us understand them better.

Political and Social Writings

Shaw wrote many political and social commentaries. These appeared in pamphlets, essays, books, newspaper articles, and as introductions to his plays. Many of his early political writings were published without his name, representing the Fabian Society's views.

After 1900, Shaw increasingly shared his ideas through his plays. Critics noted that his plays were a "pleasant means" of spreading his socialist ideas. His book The Intelligent Woman's Guide (1928) was praised by some as very important.

Shaw's growing interest in strong leaders was clear in his later statements. In the 1930s, he praised Hitler, Mussolini, and Stalin, saying they were "trying to get something done." He supported Stalin's government throughout the decade. In his last political book, Everybody's Political What's What, Shaw blamed the Allies for Hitler's rise.

Shaw also became interested in "creative evolution," his version of eugenics, which is the idea of improving the human race by controlling who has children. He wrote about this in his book The Revolutionist's Handbook (1903) and in Back to Methuselah. Some of his comments on this topic were very strong, and people debated if he was joking or serious.

Fiction

Shaw mostly wrote novels between 1879 and 1885, but they were not very successful. Immaturity (1879) was partly about his own life. The Irrational Knot (1880) criticized traditional marriage. Shaw liked his third novel, Love Among the Artists (1881), thinking it was a turning point for him. Cashel Byron's Profession (1882) criticized society. An Unsocial Socialist (1883) was meant to be part of a larger work about the fall of capitalism.

His only other major fiction was his 1932 story The Adventures of the Black Girl in Her Search for God. This story was about a girl searching for God and finding a more worldly answer. It upset some religious people and was banned in Ireland.

Letters and Diaries

Shaw wrote a huge number of letters throughout his life. Over 2,600 of his letters have been published. He wrote to many people, including friends, actors, and other writers.

Shaw's diaries from 1885–1897 were published in two large volumes in 1986. They give a lot of information about his life and English society in the late Victorian era. After 1897, he stopped keeping a diary because he was too busy writing other things.

Other Writings

Shaw wrote about many different topics in his journalism and books. He was interested in vegetarianism, religion, language, cinema, and photography. Collections of his writings on these subjects were published, mostly after his death.

Shaw did not write a full autobiography. He gave interviews and wrote short sketches about himself. In 1939, he put some of these together in a book called Shaw Gives Himself Away, which he later revised as Sixteen Self Sketches.

Shaw's Beliefs and Opinions

Shaw often held many beliefs, and sometimes they seemed to contradict each other. This was partly because he liked to challenge people's ideas. One thing he was always consistent about was his unusual spelling and punctuation. He preferred older spellings and often left out apostrophes. In his will, Shaw wanted his money to be used to create a new, phonetic English alphabet. This plan was complicated, but some money was eventually used to publish a special phonetic edition of Androcles and the Lion.

Shaw's views on religion changed over time. As a young man, he said he was an atheist. Later, he called himself a "mystic." In 1913, he said he was not religious "in the sectarian sense" but admired Jesus. In his will, he said his beliefs were those of "a believer in creative revolution." He asked that no one claim he belonged to any specific religious group.

Shaw believed in racial equality and marriage between people of different races. He spoke out against anti-Semitism, calling it "the hatred of the lazy, ignorant fat-headed Gentile for the pertinacious Jew."

In 1903, Shaw joined a debate about vaccination against smallpox. He called vaccination "a peculiarly filthy piece of witchcraft." He thought better housing for the poor would do more to stop diseases. Shaw was also very interested in transport, including bicycles, cars, and planes. He even joined the British Interplanetary Society when he was in his nineties.

Shaw preferred to be called "Bernard Shaw" rather than "George Bernard Shaw," but he often used his full initials, G.B.S., as a by-line. He left instructions in his will for his works to be published under the name Bernard Shaw.

Shaw's Legacy and Influence

In Theater

Shaw, arguably the most important English-language playwright after Shakespeare, produced an immense oeuvre, of which at least half a dozen plays remain part of the world repertoire.... Academically unfashionable, of limited influence even in areas such as Irish drama and British political theatre where influence might be expected, Shaw's unique and unmistakable plays keep escaping from the safely dated category of period piece to which they have often been consigned.

Shaw did not create a specific "school" of playwrights. However, many experts believe he is second only to Shakespeare in British theater. He helped create "intelligent" theater, where audiences had to think. This opened the way for many 20th-century playwrights.

Many playwrights were influenced by Shaw. Noël Coward based an early comedy on Shaw's You Never Can Tell. Even T. S. Eliot, who was not a fan, admitted that parts of his play Murder in the Cathedral might have been influenced by Saint Joan. Among more recent British playwrights, Tom Stoppard is seen as very "Shavian."

Shaw's influence quickly spread to America. He was successful there ten years before he achieved similar success in Britain. Many American writers, like Eugene O'Neill and Elmer Rice, said Shaw inspired them.

In 1976, one critic called Shaw the leading English-language playwright of the 20th century. However, the playwright John Osborne strongly disagreed, calling Shaw "the most fraudulent, inept writer of Victorian melodramas." Despite this, Shaw's influence can still be seen in some of Osborne's plays.

Shaw also fought against theater censorship, which finally ended in Britain in 1968. He also worked for many years to establish a National Theatre. His short play The Dark Lady of the Sonnets (1910) was part of this effort.

In recent years, Shaw's reputation has grown again. Many of his major plays are being performed, showing how relevant his ideas still are today. The Shaw Festival in Canada performs plays by Shaw and other works from his time. The Gingold Theatrical Group in New York City also promotes Shaw's humanitarian ideas.

General Influence

In the 1940s, one author advised against accepting Shaw's home, Shaw's Corner, as a gift to the nation. He thought Shaw would be forgotten in 50 years. But Shaw's influence has lasted. The term "Shavian" is still widely used, and Shaw Societies exist around the world. The first society was founded in London in 1941.

Shaw also left a musical legacy. Even though he disliked his plays being turned into musicals, two were: Arms and the Man became The Chocolate Soldier (1908), and Pygmalion became the famous My Fair Lady (1956). Shaw also played a role in getting the BBC to commission Edward Elgar's Third Symphony.

The impact of Shaw's political ideas is debated. One friend said he had "produced so little effect on his generation." Another believed he had a strong influence on the social and political life of his time.

See also

In Spanish: George Bernard Shaw para niños

In Spanish: George Bernard Shaw para niños

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |