John Osborne facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John Osborne

|

|

|---|---|

Osborne rehearsing on the set of First Love (1970)

|

|

| Born | John James Osborne 12 December 1929 Fulham, London, England |

| Died | 24 December 1994 (aged 65) Clun, Shropshire, England |

| Occupation |

|

| Nationality | British |

| Period | 1950–1992 |

| Genre |

|

| Literary movement | Angry Young Men |

| Notable works | Look Back in Anger The Entertainer Inadmissible Evidence |

| Spouse | Pamela Lane Mary Ure Penelope Gilliatt Jill Bennett Helen Dawson |

| Children | 1 daughter (with Gilliatt) |

John James Osborne (born December 12, 1929 – died December 24, 1994) was an English writer for plays, movies, and a performer. He was famous for his plays that questioned the way society and politics worked. His most well-known play is Look Back in Anger, which came out in 1956.

Osborne was one of the first writers to explore Britain's role in the world after the British Empire ended.

Contents

John Osborne's Early Life

Osborne was born in London on December 12, 1929. His father, Thomas Godfrey Osborne, was an artist and writer for advertisements. His mother, Nellie Beatrice Grove, worked as a barmaid.

In 1935, his family moved to Stoneleigh in Surrey, hoping for a better life. However, Osborne felt it was a very boring place. He loved his father but did not get along with his mother.

Thomas Osborne died in 1941. He left his son some insurance money. John used this money to attend Belmont College, a private school. He started there in 1943 but was asked to leave in 1945. Osborne said it was because he hit the headmaster for listening to music. Another student said he was fighting with other pupils. A School Certificate was the only official school paper he earned.

After school, Osborne went back to London. He briefly tried working in journalism for businesses. He then got a job helping a group of young actors on tour. This led him to the theatre. He soon became a stage manager and actor. He joined a touring theatre company. Osborne started writing plays. His first play, The Devil Inside Him, was co-written with his mentor, Stella Linden. It was performed in 1950. His second play, Personal Enemy, was written with Anthony Creighton. These plays were shown in smaller theatres before he wrote Look Back in Anger.

Look Back in Anger Play

Osborne wrote Look Back in Anger in just 17 days. He wrote it while sitting in a deck chair on Morecambe pier. At the time, he was acting in another play there. Osborne's play was largely based on his own life. It was about his time living and arguing with his first wife, Pamela Lane.

He sent the play to many agents in London, but they all said no. Osborne later wrote that he felt a kind of relief when it was quickly sent back. Finally, he sent it to the new English Stage Company at London's Royal Court Theatre.

The company needed a successful play to survive. Its first three shows had not done well. The director, George Devine, decided to take a chance on Osborne's play. He saw that it showed a strong new feeling about life after the war. Osborne was living on a houseboat at the time. Devine rowed out to the boat to tell him he wanted to produce the play. Tony Richardson directed the play. It starred Kenneth Haigh, Mary Ure, and Alan Bates. A press officer at the theatre came up with the phrase "angry young man" to describe the play's style.

The first reviews for Look Back in Anger were mixed. Many critics thought it was not good at first. But the play later became a huge success. It moved to the West End in London and then to Broadway in New York. It even toured to Moscow. A movie version came out in 1959. The play made Osborne famous. He won the Evening Standard Drama Award for the most promising playwright of 1956.

The Entertainer and 1960s Plays

When Laurence Olivier first saw Look Back in Anger, he did not think much of it. Olivier was making a movie with Marilyn Monroe at the time. Her husband, the writer Arthur Miller, was with her. Olivier asked Miller what plays he wanted to see in London. Miller suggested Osborne's play because of its title. Olivier tried to talk him out of it, but Miller insisted. They went to see it together.

Miller found the play amazing. He and Olivier went backstage to meet Osborne. Olivier was impressed by Miller's reaction. He then asked Osborne for a part in his next play. George Devine, the director of the Royal Court, sent Olivier the unfinished script for The Entertainer. Olivier eventually took the main role. He played Archie Rice, a failing music-hall performer. He performed it successfully at the Royal Court and in the West End.

The Entertainer uses the idea of the dying music hall shows. It compares this to the end of the British Empire's power. It also shows how the United States was becoming more powerful. This play was set during the Suez Crisis of November 1956. Critics praised The Entertainer.

After The Entertainer, Osborne wrote The World of Paul Slickey (1959). This was a musical that made fun of tabloid newspapers. He also wrote a TV play called A Subject of Scandal and Concern (1960). Then came two plays together, Plays for England, in 1962. These were The Blood of the Bambergs and Under Plain Cover.

Luther, a play about the life of Martin Luther, was first performed in 1961. It moved to Broadway and won Osborne a Tony Award. Inadmissible Evidence was first performed in 1964. In 1963, Osborne won an Oscar for his movie script for Tom Jones. His 1965 play, A Patriot for Me, was about the Austrian Redl case. This play helped to end the system of theatre censorship in Britain.

Both A Patriot For Me and The Hotel in Amsterdam (1968) won Evening Standard Best Play of the Year awards. The Hotel in Amsterdam is about three couples from show business. They are staying in a hotel after running away from a difficult movie producer.

Later Life and Works

John Osborne's plays in the 1970s included West of Suez, which starred Ralph Richardson. He also wrote A Sense of Detachment (1972) and Watch It Come Down (1976).

During the 1970s, Osborne also acted in movies. He played a gangster named Cyril Kinnear in Get Carter (1971). He later appeared in Tomorrow Never Comes (1978) and Flash Gordon (1980).

In the 1980s, Osborne lived in Shropshire and wrote a diary for The Spectator magazine. He opened his garden to visitors to raise money for his local church. He had returned to the Church of England around 1974.

In the last 20 years of his life, Osborne wrote two books about his own life. These were A Better Class of Person (1981) and Almost a Gentleman (1991). A Better Class of Person was made into a TV film in 1985. It was nominated for an award called the Prix Italia.

Osborne's last play was Déjàvu (1991). It was a follow-up to Look Back in Anger. His two life story books were re-released together in 1999.

Impact on Theatre

Osborne's plays changed British theatre. He helped make it respected again as an art form. He broke away from the old, formal rules of plays. He brought attention back to strong language and deep emotions in theatre. He believed theatre could help ordinary people break down social barriers. He wanted his plays to remind people of real joys and real pains.

Osborne did change the world of theatre. He influenced other playwrights like Edward Albee and Mike Leigh. However, plays as original as his remained rare. Osborne was not surprised by this. He understood the less glamorous side of theatre very well. He received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Writer's Guild of Great Britain.

Politics and Personal Life

Osborne joined the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament in 1959. Later, he became more independent in his political views. He saw himself as someone who wanted change but also disliked it.

Osborne was married five times. His last marriage seemed to be the happiest.

Marriages

Pamela Lane (1951–1957)

Osborne felt a strong connection to his first wife, Pamela Lane. They were both actors in a theatre group. They married in secret in 1951. They lived in different places around London and on tour. Pamela's acting career did well, but Osborne's struggled. They divorced in 1957. Later, in the 1980s, they wrote to each other often and met in secret.

Mary Ure (1957–1963)

Osborne started a relationship with Mary Ure after she was cast in Look Back in Anger in 1956. They moved in together. Ure later left Osborne for the actor Robert Shaw.

Penelope Gilliatt (1963–1968)

Osborne met his third wife, Penelope Gilliatt, who was a writer. They were together for seven years, married for five of them. They had one daughter, Nolan. Osborne and Gilliatt's marriage faced challenges because Osborne wanted her to stop her writing career and focus on him.

Jill Bennett (1968–1977)

Osborne had a difficult nine-year marriage to the actress Jill Bennett.

Helen Dawson (1978–1994)

Helen Dawson (1939–2004) was a journalist and critic. This last marriage of Osborne's lasted until his death and was a happy one. Helen worked to keep Osborne's work and memory alive after he passed away.

Osborne died owing a lot of money. His last word to Helen was "Sorry". Helen Dawson died in 2004 and is buried next to him.

Vegetarianism

Around the time he wrote Look Back in Anger, Osborne was a vegetarian. This was considered unusual at the time.

Death

After a serious liver problem in 1987, Osborne developed diabetes. He had to inject insulin every day. He died in 1994 from problems related to his diabetes. He was 65 years old. He is buried in St George's churchyard in Clun, Shropshire. His last wife, Helen Dawson, is buried next to him.

John Osborne's Archive

Osborne started sending his papers to the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas in Austin in the 1960s. He continued to add to them throughout his life. This main collection has over 50 boxes of materials. It includes typed and handwritten copies of his works, letters, articles, scrapbooks, and business papers.

In 2008, the Ransom Center bought another collection of over 30 boxes. These had been kept by Helen Dawson Osborne. This collection mostly covers the later years of Osborne's life. It also includes notebooks he had kept separate from his first collection.

Works by John Osborne

| Title | Type | Year | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Devil Inside Her | Theatre | 1950 | with Stella Linden |

| The Great Bear | Theatre | 1951 | never produced |

| Personal Enemy | Theatre | 1955 | with Anthony Creighton |

| Look Back in Anger | Theatre | 1956 | |

| The Entertainer | Theatre | 1957 | |

| Epitaph for George Dillon | Theatre | 1958 | with Anthony Creighton |

| The World Of Paul Slickey | Theatre | 1959 | |

| A Subject of Scandal and Concern | TV | 1960 | |

| Luther | Theatre | 1961 | |

| The Blood of the Bambergs | Theatre | 1962 | |

| Under Plain Cover | Theatre | 1962 | |

| Tom Jones | Screenplay | 1963 | |

| Inadmissible Evidence | Theatre | 1964 | |

| A Patriot for Me | Theatre | 1965 | |

| A Bond Honoured | Theatre | 1966 | One-act play |

| The Hotel in Amsterdam | Theatre | 1968 | |

| Time Present | Theatre | 1968 | |

| The Charge of the Light Brigade | Screenplay | 1968 | |

| The Parachute | TV | 1968 | |

| The Right Prospectus | TV | 1970 | |

| West of Suez | Theatre | 1971 | |

| A Sense of Detachment | Theatre | 1972 | |

| The Gift of Friendship | TV | 1972 | |

| Hedda Gabler | Theatre | 1972 | Ibsen adaptation |

| A Place Calling Itself Rome | Theatre | 1973 | Coriolanus adaptation, never produced |

| Ms, Or Jill And Jack | TV | 1974 | |

| The End of Me Old Cigar | Theatre | 1975 | |

| The Picture Of Dorian Gray | Theatre | 1975 | Wilde adaptation |

| Almost A Vision | TV | 1976 | |

| Watch It Come Down | Theatre | 1976 | |

| Try A Little Tenderness | Theatre | 1978 | never produced |

| Very Like A Whale | TV | 1980 | |

| You're Not Watching Me, Mummy | TV | 1980 | |

| A Better Class of Person | Book | 1981 | autobiography volume I |

| A Better Class of Person | TV | 1985 | |

| God Rot Tunbridge Wells! | TV | 1985 | |

| The Father | Theatre | 1989 | Strindberg adaptation |

| Almost a Gentleman | Book | 1991 | autobiography volume II |

| Déjàvu | Theatre | 1992 |

Filmography

| Title | Year | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| First Love | 1970 | Maidanov | |

| The Chairman's Wife | 1971 | Bernard Howe | |

| Get Carter | 1971 | Cyril Kinnear | |

| Tomorrow Never Comes | 1978 | Lyne | |

| Flash Gordon | 1980 | Arborian Priest |

Images for kids

-

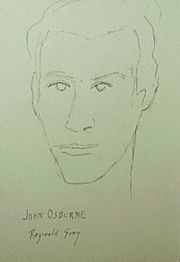

Osborne in 1957, painted by Irish artist Reginald Gray.

-

Graves of Osborne and his fifth wife in Clun churchyard

See also

In Spanish: John Osborne para niños

In Spanish: John Osborne para niños

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |