William Morris facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

William Morris

|

|

|---|---|

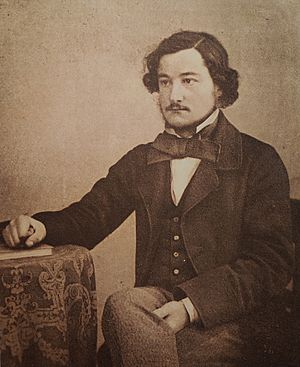

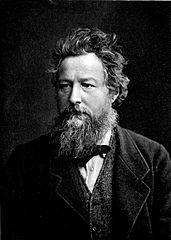

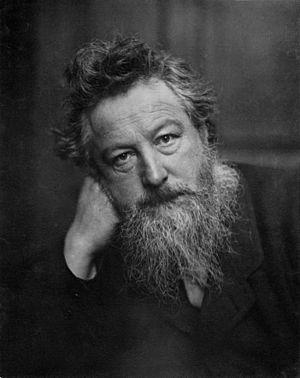

William Morris by Frederick Hollyer, 1887

|

|

| Born | 24 March 1834 Walthamstow, Essex, England

|

| Died | 3 October 1896 (aged 62) Hammersmith, England

|

| Education | Exeter College, Oxford |

| Occupation |

|

| Known for |

|

|

Notable work

|

News from Nowhere, The Well at the World's End |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | Jenny Morris May Morris |

| Signature | |

William Morris (born March 24, 1834 – died October 3, 1896) was a very talented British artist, writer, and social activist. He was a key figure in the Arts and Crafts Movement, which focused on traditional craftsmanship. Morris helped bring back old British ways of making textiles. He also played a big part in creating the modern fantasy writing style. Later in his life, he became an important voice for socialism in Great Britain.

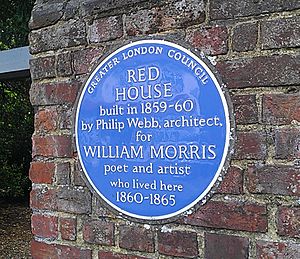

Morris grew up in a rich family in Walthamstow, Essex, England. While studying at Oxford University, he became very interested in the Middle Ages. After college, he married Jane Burden. He also became good friends with Pre-Raphaelite artists like Edward Burne-Jones and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. He also befriended the architect Philip Webb. Webb and Morris designed a special house called Red House in Kent. Morris lived there from 1859 to 1865.

In 1861, Morris started a company called Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. with his friends. They created beautiful decorative items for homes. This company became very popular and influenced how people decorated their homes during the Victorian period. Morris designed many things, including tapestries, wallpaper, fabrics, furniture, and stained glass windows. In 1875, he took full control of the company, renaming it Morris & Co.

From 1871, Morris rented a country home called Kelmscott Manor in Oxfordshire. He also kept a main home in London. He was inspired by trips to Iceland and translated many Icelandic Sagas into English. He also became a successful writer of epic poems and novels, such as The Earthly Paradise (1868–1870) and News from Nowhere (1890). In 1877, he started the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings to protect old buildings from damage. In the 1880s, he became a strong supporter of socialism. He even started the Socialist League in 1884. In 1891, he founded the Kelmscott Press. This press made beautiful, old-style printed books, which he focused on in his final years.

William Morris is seen as one of the most important cultural figures of Victorian Britain. During his lifetime, he was best known as a poet. However, after his death, he became more famous for his designs. The William Morris Society was created in 1955 to honor his work. Many of his designs are still made today.

Contents

William Morris's Early Life

Growing Up: 1834–1852

William Morris was born on March 24, 1834, in Walthamstow, Essex. His family was wealthy and middle-class. His father was a financier in London. His mother, Emma Morris, came from a rich family in Worcester. William was the third of his parents' surviving children. He had two older sisters, Emma and Henrietta. Later, he had more siblings: Stanley, Rendall, Arthur, Isabella, Edgar, and Alice. The Morris family was Evangelical Protestant. William was baptised at St. Mary's Church, Walthamstow.

As a child, William stayed home a lot. He loved reading, especially the novels of Walter Scott. When he was six, his family moved to Woodford Hall in Woodford, Essex. This large house was surrounded by 50 acres of land next to Epping Forest. He enjoyed fishing with his brothers and gardening. He spent much time exploring the forest. He was fascinated by old Iron Age earthworks and the Hunting Lodge at Chingford. He also rode his pony through the countryside. He visited many churches and cathedrals, admiring their architecture. His father took him on trips to places like Canterbury Cathedral and the Isle of Wight.

At age nine, he went to Misses Arundale's Academy for Young Gentlemen. He disliked this preparatory school. In 1847, Morris's father died suddenly. The family then relied on money from copper mines. They sold Woodford Hall and moved to the smaller Water House. In February 1848, Morris started at Marlborough College in Marlborough, Wiltshire. He was called "Crab" there and felt bullied and homesick. However, he visited many ancient sites in Wiltshire, like Avebury. The school was Anglican. In March 1849, Morris became very interested in the Anglo-Catholic movement. At Christmas 1851, he left the school. He returned to Water House and was taught by a private tutor.

Oxford University & Friends: 1852–1856

In June 1852, Morris started at Exeter College at Oxford University. He began living there in January 1853. He did not like how they taught Classics. Instead, he became very interested in Medieval history and architecture. He was inspired by Oxford's many Medieval buildings. This interest was part of Britain's growing Medievalist movement. This movement rejected many ideas of Victorian industrial capitalism. Morris saw the Middle Ages as a time of chivalric values and strong community. He thought this was better than his own time. He read Thomas Carlyle's book Past and Present (1843). This book praised Medieval values to fix Victorian problems. Because of this, Morris disliked modern capitalism more and more. He was also influenced by Christian socialists like Charles Kingsley.

At college, Morris met Edward Burne-Jones, who became his lifelong friend. They had similar interests, including Anglo-Catholicism and Arthurian legends. Through Burne-Jones, Morris joined a group of students from Birmingham. They called themselves the "Brotherhood" and are known as the Birmingham Set. Morris was the richest in the group and was generous with his money. They all liked the poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson and would read William Shakespeare's plays together.

Morris was greatly influenced by the art critic John Ruskin. He especially loved Ruskin's chapter "On the Nature of Gothic Architecture" from The Stones of Venice. Morris later called it "one of the very few necessary and inevitable utterances of the century." Morris adopted Ruskin's idea to reject cheap, factory-made art. He wanted to return to hand-craftsmanship. He believed artisans should be seen as artists. Art should be affordable and handmade, with no art forms being more important than others. Ruskin was famous for supporting the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. This group of painters had a Medieval and Romantic style. They used lots of detail, bright colors, and complex designs. Morris and his friends were very impressed by them. Influenced by Ruskin and John Keats, Morris started writing more poetry in a similar style.

Morris and Burne-Jones were both interested in Romanticism and Anglo-Catholicism. They thought about becoming clergymen and starting a monastery. There, they would live simply and focus on art. But Morris became more critical of the Church of England, and this idea faded. In summer 1854, Morris went to Belgium to see Medieval paintings. In July 1855, he traveled with Burne-Jones and another friend through northern France. They visited many Medieval churches. On this trip, he and Burne-Jones decided to dedicate their lives to art. This decision caused some tension with his family. They wanted him to work in business or the church. Later, in Birmingham, Morris found Thomas Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur. This book became very important for his and Burne-Jones's interest in Arthurian stories. In January 1856, Morris and his friends started The Oxford and Cambridge Magazine. Morris mostly funded it and wrote many stories, poems, and reviews. The magazine lasted for twelve issues and was praised by Tennyson and Ruskin.

Learning & Marriage: 1856–1859

After finishing his studies and getting his degree, Morris began working with the architect George Edmund Street in January 1856. Street was known for his Neo-Gothic style. Morris learned architectural drawing. He worked under a young architect named Philip Webb, who became a close friend. Morris soon moved to Street's London office. In August 1856, he moved into a flat in Bloomsbury with Burne-Jones. Morris found London fascinating but was upset by its pollution and fast growth. He called it "the spreading sore."

William Morris became very interested in the peaceful Medieval scenes in Pre-Raphaelite paintings. He spent a lot of money buying these artworks. Burne-Jones shared this interest and became an apprentice to Dante Gabriel Rossetti, a leading Pre-Raphaelite painter. The three soon became close friends. Through Rossetti, Morris met other artists and writers like Robert Browning. Morris grew tired of architecture and decided to try painting instead, in the Pre-Raphaelite style. Morris helped Rossetti and Burne-Jones paint Arthurian murals at the Oxford Union. His contributions were not as skilled as the others. At Rossetti's suggestion, Morris and Burne-Jones moved into a flat at No. 17 Red Lion Square in November 1856. Morris designed and ordered Medieval-style furniture for the flat. He painted it with Arthurian scenes, going against popular art tastes.

Morris also continued writing poetry. He started designing illuminated manuscripts and embroidered hangings. In March 1857, Bell and Dandy published his book of poems, The Defence of Guenevere. Morris paid for it himself. It did not sell well and got few good reviews. Disappointed, Morris did not publish another book for eight years. In October 1857, Morris met Jane Burden at a theatre. She came from a poor working-class family. Rossetti first asked her to model for him. Both Rossetti and Morris were very taken with her. Morris began a relationship with her, and they got engaged in spring 1858. They married quietly at St Michael at the North Gate church in Oxford on April 26, 1859. They honeymooned in Bruges, Belgium, and then lived temporarily in London.

William Morris's Career and Fame

Red House & The Firm: 1859–1865

Morris wanted a new home for himself and his family. This led to the building of Red House in Upton, Kent, about ten miles from central London. Morris focused on the inside design, while Philip Webb designed the outside. The house was named for its red bricks and red tiles. It was L-shaped, which was unusual for the time. It was influenced by Neo-Gothic architecture but was still unique. Morris called it "very mediaeval in spirit." The house and garden were designed to fit together. It took a year to build and cost Morris £4000. Burne-Jones called it "the beautifullest place on Earth."

After it was built, Morris invited friends to visit. These included Burne-Jones and his wife Georgiana, and Rossetti and his wife Lizzie Siddal. They helped him paint murals on the furniture, walls, and ceilings. Many of these paintings were based on Arthurian tales, the Trojan War, and Geoffrey Chaucer's stories. Morris also designed floral embroideries for the rooms. They often played games like hide and seek and sang with piano music.

In April 1861, Morris started a decorative arts company called Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co.. He had six partners: Burne-Jones, Rossetti, Webb, Ford Madox Brown, Charles Faulkner, and Peter Paul Marshall. They called themselves "the Firm." They wanted to use Ruskin's ideas to improve British production. They aimed to make decoration a fine art again. They also believed in making art affordable and available to everyone. They hired boys from a home for poor boys in London. Many of these boys were trained as apprentices.

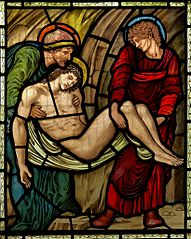

The Firm used the Neo-Gothic style. They wanted to go back to Medieval Gothic craftsmanship. Their products included furniture, carvings, metalwork, stained glass windows, and murals. Their stained glass windows were very popular early on. Many churches were being built or renovated in the Neo-Gothic style. The architect George Frederick Bodley often commissioned their windows. Even though Morris wanted art for everyone, the Firm became popular with wealthy people. This was especially true after their display at the 1862 International Exhibition in South Kensington. They got good press and awards. However, other design companies, especially those in the Neo-Classical style, opposed them.

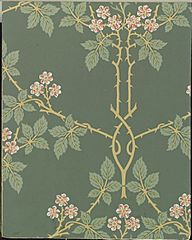

Morris slowly stopped painting. He realized his paintings lacked movement. None of his paintings are dated after 1862. Instead, he focused on designing wallpaper patterns. His first was "Trellis" in 1862. Jeffrey and Co. of Islington produced his designs from 1864 under his supervision. Morris was active in various groups. He joined the Hogarth Club and the Mediaeval Society.

Meanwhile, Morris's family grew. In January 1861, his first daughter, Jane Alice Morris (known as "Jenny"), was born. In March 1862, their second daughter, Mary "May" Morris, was born. Morris was a loving father. Both daughters later said they had happy childhoods.

Morris had hoped to create an artistic community at Upton. He planned a second house next to Red House for Burne-Jones's family. But these plans were dropped when Burne-Jones's son died. By 1864, Morris was tired of living at Red House. He disliked the long daily commute to London. He sold Red House. In autumn 1865, he moved his family to No. 26 Queen Square in Bloomsbury. The Firm had also moved its offices there earlier that summer.

Queen Square & The Earthly Paradise: 1865–1870

At Queen Square, the Morris family lived in a flat above the Firm's shop. Janey's sister and household servants also lived with them. The Firm saw some changes. Faulkner left, and Warrington Taylor was hired as a business manager until 1866. Taylor organized the Firm's money and helped Morris stay on schedule. During these years, the Firm completed several important designs. From September 1866 to January 1867, they redecorated the Armoury and Tapestry Room in St James's Palace. In 1867, they designed the Green Dining Room at the South Kensington Museum (now the Morris Room). People in the United States became interested in the Firm's work. Morris met Henry James and Charles Eliot Norton. Despite its success, the Firm was not making a huge profit. Morris's investments also decreased in value, so he had to spend less.

Morris's relationship with his mother improved. He often took his wife and children to visit her in Leyton. He also went on holidays. In summer 1866, he, Webb, and Taylor toured churches in northern France.

In August 1866, Morris joined the Burne-Jones family on holiday in Lymington. In August 1867, both families holidayed together in Oxford. In August 1867, the Morrises went to Southwold, Suffolk. In summer 1869, Morris took his wife to Bad Ems in Germany. They hoped the local waters would help her health. While there, he enjoyed walks and focused on writing poetry.

Morris continued to spend much time writing poetry. In 1867, Bell and Dandy published his epic poem, The Life and Death of Jason. Morris paid for it himself. The book retold the ancient Greek myth of Jason and his quest for the Golden Fleece. Unlike his earlier book, The Life and Death of Jason was well received. The publishers paid Morris for the second edition. From 1865 to 1870, Morris worked on another epic poem, The Earthly Paradise. It was a tribute to Chaucer. It had 24 stories from different cultures, each told by a different narrator. The story was set in the late 14th century. It was about Norsemen fleeing the Black Death who found an island where people still worshipped ancient Greek gods. F. S. Ellis published it in four parts. It quickly became popular and made Morris a famous poet.

Kelmscott Manor & Iceland: 1870–1875

By 1870, Morris was a well-known public figure in Britain. The press often asked for his photographs, which he disliked. That year, he also sat for a portrait by the painter George Frederic Watts. Morris was very interested in Icelandic literature. He became friends with the Icelandic theologian Eiríkur Magnússon. Together, they translated the Eddas and Sagas into English. Morris also loved creating handwritten illuminated manuscripts. He made 18 such books between 1870 and 1875. The first was A Book of Verse, a birthday gift for Georgina Burne-Jones. Twelve of these were copies of Nordic tales. Morris believed calligraphy was an art form. He taught himself Roman and italic script and how to make gilded letters. In November 1872, he published Love is Enough, a poetic play based on a Medieval Welsh story. It was illustrated with Burne-Jones woodcuts but was not very popular. By 1871, he started a novel set in the present, The Novel on Blue Paper, about a love triangle. It was never finished.

By early summer 1871, Morris looked for a house outside London. He wanted his children to escape the city's pollution. He chose Kelmscott Manor in the village of Kelmscott, Oxfordshire. He shared the tenancy with Rossetti starting in June. Morris loved the building, built around 1570. He spent much time in the countryside there. Rossetti, however, was unhappy at Kelmscott. Morris divided his time between London and Kelmscott. He became tired of his family home in Queen Square. In January 1873, he moved his family to Horrington House in West London. This put him much closer to Burne-Jones's home. They met almost every Sunday morning for the rest of Morris's life.

Leaving Jane and his children with Rossetti at Kelmscott, Morris went to Iceland in July 1871. He traveled with Faulkner, W. H. Evans, and Eiríkur. They sailed from Granton, Scotland, to Reykjavík, Iceland. There, they met Jón Sigurðsson, the President of the Althing. Morris supported the Icelandic independence movement. From Reykjavík, they traveled by Icelandic horse along the south coast. They visited places like Þórsmörk and Þingvellir. They returned to Britain in September. In April 1873, Morris and Burne-Jones holidayed in Italy, visiting Florence and Siena. Morris generally disliked Italy but was interested in Florentine Gothic architecture. Soon after, in July, Morris returned to Iceland. He revisited many places and went north to Vatna glacier. His two trips to Iceland greatly influenced him. He said these trips made him realize that "the most grinding poverty is a trifling evil compared with the inequality of classes."

Morris and Burne-Jones then spent time with a wealthy supporter of the Firm, George Howard, 9th Earl of Carlisle, and his wife Rosalind. They stayed at their Medieval home, Naworth Castle, in Cumberland. In July 1874, the Morris family took Burne-Jones's two children on holiday to Bruges, Belgium. By this time, Morris's friendship with Rossetti had weakened. In July 1874, Rossetti left Kelmscott, and Morris's publisher F.S. Ellis took his place. The company's other partners were working on different projects. Morris decided to take full control of the Firm. In March 1875, he paid £1000 each to Rossetti, Brown, and Marshall as compensation. The other partners did not ask for money. That month, the Firm was officially closed and replaced by Morris & Co. Burne-Jones and Webb continued to design for it. After this, Morris resigned from his directorship of the Devon Great Consols and sold his shares.

Textile Work & Politics: 1875–1880

Now in full control of the Firm, Morris became very interested in textile dyeing. He worked with Thomas Wardle, a silk dyer in Leek, Staffordshire. Morris spent time with Wardle at his home between summer 1875 and spring 1878. Morris thought chemical aniline dyes were poor quality. He wanted to bring back natural dyes. He used indigo for blue, walnut shells for brown, and cochineal or madder for red. Working in this industrial setting, he saw how goods were made and how workers lived. He was disgusted by the poor living conditions and pollution. These experiences greatly shaped his political views. After learning to dye, Morris focused on weaving in the late 1870s. He experimented with silk weaving at Queen's Square.

In spring 1877, the Firm opened a store at No. 449 Oxford Street. They hired new, skilled staff. As a result, sales increased, and the company became more popular. By 1880, Morris & Co. was a well-known name. It was very popular with Britain's upper and middle classes. The Firm received more and more orders from wealthy people. Morris furnished parts of St James's Palace and the chapel at Eaton Hall. Because of his growing sympathy for working-class people, Morris felt conflicted. He privately called it "ministering to the swinish luxury of the rich."

Morris continued his writing. He translated Virgil's Aeneid, calling it The Aeneids of Vergil (1876). Many translations already existed, often by trained Classicists. But Morris said his unique view was as "a poet not a pedant." He also kept translating Icelandic tales with Magnússon, including Three Northern Love Stories (1875). In 1877, Oxford University offered Morris the honorary position of Professor of Poetry. He declined, saying he felt unqualified.

In summer 1876, Jenny Morris was diagnosed with epilepsy. Morris refused to let her be isolated or put in an institution, which was common then. He insisted the family care for her. When Janey took May and Jenny to Oneglia in Italy, Jenny had a serious seizure. Morris rushed to Italy to see her. They then visited other cities like Venice and Verona. Morris gained a greater appreciation for Italy than on his previous trip. In April 1879, Morris moved his family again. He rented an 18th-century mansion in Hammersmith, West London. It was owned by the novelist George MacDonald. Morris named it Kelmscott House and decorated it to his taste. He set up a workshop in the grounds to make hand-knotted carpets. Both his homes were along the River Thames. In August 1880, he and his family took a boat trip along the river from Kelmscott House to Kelmscott Manor.

Morris became active in politics during this time. He joined the radicalist movement within British liberalism. In November 1876, he became treasurer of the Eastern Question Association (EQA). This group opposed Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli's alliance with the Ottoman Empire. The EQA highlighted the Ottoman massacre of Bulgarians. They feared Disraeli would join the Ottomans in war against Russia. Morris actively campaigned. He wrote the song "Wake, London Lads!" for a rally against military action. Morris eventually became disappointed with the EQA. He called it "full of wretched little personalities." He joined a group of mostly working-class EQA activists, the National Liberal League. He became their treasurer in summer 1879. This group remained small, and Morris resigned in late 1881.

His unhappiness with the British liberal movement grew after William Ewart Gladstone became Prime Minister in 1880. Morris was angry that Gladstone's government did not reverse Disraeli's actions. He felt that Radicalism was "on the wrong line" and would always be controlled by rich capitalists.

In 1876, Morris visited the Church of St John the Baptist, Burford. He was shocked by the restoration done by his old mentor, G. E. Street. He realized that these restorations destroyed old features. They replaced them with "sham old" features. To fight this trend, in March 1877, he founded the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB). He called it "Anti-Scrape." He became the honorary secretary and treasurer. Most early SPAB members were his friends. The group's ideas came from Ruskin's The Seven Lamps of Architecture (1849). Morris tried to connect with art and history societies. He also contacted the press to promote his cause. He strongly criticized the restoration of Tewkesbury Abbey. In autumn 1879, Morris campaigned to protect St Mark's Basilica in Venice from restoration. He gathered a petition with 2000 signatures, including Disraeli, Gladstone, and Ruskin.

William Morris's Later Life

Merton Abbey & Democratic Federation: 1881–1884

In summer 1881, Morris leased the Merton Abbey Works. This was a seven-acre former silk weaving factory next to the River Wandle in Merton, Southwest London. He moved his workshops there. The site was used for weaving, dyeing, and making stained glass. Within three years, 100 craftspeople worked there. Working conditions at the Abbey were better than most Victorian factories. However, workers had little chance to show their own creativity. Morris had a system of profit sharing for the Firm's top clerks. But most workers were paid by piecework. Morris knew his company did not fully meet his ideals. He said it was impossible to run a socialist company in a capitalist economy. The Firm was expanding. It opened a store in Manchester in 1883. It also had a stand at the Foreign Fair in Boston that year.

Rossetti died in April 1882. Morris said Rossetti had "some of the very greatest qualities of genius." He felt Rossetti could have been a great man if not for his "arrogant misanthropy."

In January 1881, Morris helped set up the Radical Union. This group aimed to challenge the Liberals. Morris became a member of its executive committee. However, he soon rejected liberal radicalism completely. He moved towards socialism. At this time, British socialism was a small, new movement with only a few hundred members. Britain's first socialist party, the Democratic Federation (DF), was founded in 1881 by Henry Hyndman. Morris joined the DF in January 1883. Morris read many books about socialism. He read Henry George's Progress and Poverty and Karl Marx's Das Kapital. He admitted Marx's economic ideas gave him "agonies of confusion." He preferred the writings of William Cobbett.

In May 1883, Morris was appointed to the DF's executive. He was soon elected treasurer. He dedicated himself to socialism. He gave lectures across Britain to gain supporters. The mainstream press often criticized him. In November 1883, he spoke at University College, Oxford. He began talking about socialism, which shocked many staff members. This gained national press coverage. In February 1884, he traveled to Blackburn, Lancashire, during a cotton strike. He lectured to the strikers about socialism. The next month, he marched in a London demonstration. It marked the anniversary of Marx's death and the Paris Commune.

Morris used his artistic and writing skills to help the DF. He designed the group's membership card. He helped write their manifesto, Socialism Made Plain. It called for better housing, free education, free school meals, an eight-hour workday, and nationalization of land, banks, and railways. Some DF members found it hard to understand how he could be a socialist and also own a company. But he was admired for his honesty. The DF started a weekly newspaper, Justice. Morris covered its financial losses. He also wrote articles for the newspaper. He became friends with another writer, George Bernard Shaw.

His socialist work took up much of his time. He had to stop translating the Persian Shahnameh. He also saw less of Burne-Jones. Burne-Jones had become more conservative and felt the DF was using Morris. Of Morris's artist friends, only Webb and Faulkner fully embraced socialism.

In 1884, the DF renamed itself the Social Democratic Federation (SDF). It was reorganizing internally. However, the group was splitting. Some, like Hyndman, wanted to achieve socialism through parliament. Others, like Morris, thought parliament was corrupt and capitalist. Morris and Hyndman also disagreed on British foreign policy. Morris was against imperialism, while Hyndman was patriotic. The conflict grew, and most activists supported Morris. In December 1884, Morris and his supporters left the SDF. This was the first major split in the British socialist movement.

Socialist League: 1884–1889

In December 1884, Morris founded the Socialist League (SL) with other former SDF members. He wrote the SL's manifesto with Bax. They called their position "Revolutionary International Socialism." They believed in proletarian internationalism and world revolution. They rejected the idea of socialism in one country. Morris wanted to "make Socialists" by educating and organizing people. He hoped socialists would take part in a proletariat revolution to create a socialist society. He told activists to avoid elections. Bax taught Morris more about Marxism. He also introduced Morris to Friedrich Engels, Marx's friend. Engels thought Morris was honest but lacked practical skills for revolution. Morris stayed in touch with other left-wing groups in London. He avoided the Fabian Society, thinking it too middle-class. Although a Marxist, he befriended anarchists like Stepniak. He was influenced by their anarchist views.

As the main leader of the League, Morris gave many speeches. He spoke on street corners, in working men's clubs, and in lecture halls across England and Scotland. He also visited Dublin to support Irish nationalism. He started a League branch at his Hammersmith house. By their first meeting in July 1885, the League had eight branches in England. It was also connected with Scottish socialist groups. As the British socialist movement grew, it faced more opposition. Police often arrested and intimidated activists. To fight this, the League joined a Defence Club with other socialist groups. Morris was treasurer. Morris strongly criticized the police's "bullying." Once, he was arrested for fighting back against an officer, but the charges were dropped. The Black Monday riots in February 1886 led to more repression against left-wing activists. In July, Morris was arrested and fined for public obstruction while speaking about socialism.

Morris oversaw the League's newspaper, Commonweal. He was its editor for six years and kept it financially stable. It was first published in February 1885. It included articles from famous socialists like Engels and Shaw. Morris also wrote articles and poems for it. In Commonweal, he published a 13-part poem, The Pilgrims of Hope, about the Paris Commune. From November 1886 to January 1887, Morris's novel, A Dream of John Ball, was published in Commonweal. It was set during the Peasants' Revolt of 1381 in Kent. It had strong socialist themes and was popular with many people. It was published as a book in 1888. Soon after, a collection of Morris's essays, Signs of Change, was published.

From January to October 1890, Morris published his novel, News from Nowhere, in Commonweal. This increased the paper's circulation. In March 1891, it was published as a book. By 1900, it was translated into several languages and became a classic among European socialists. The book combines utopian socialism and soft science fiction. It tells the story of William Guest, a socialist, who wakes up in the early 21st century. He finds a future society based on common ownership and democratic control of production. In this society, there is no private property, no big cities, no authority, no money, no divorce, no courts, and no class systems. It was Morris's vision of an ideal socialist society.

Morris also continued his translation work. In April 1887, Reeves and Turner published the first volume of his translation of Homer's Odyssey. The second volume followed in November. Morris also wrote and starred in a play, The Tables Turned; Or Nupkins Awakened. It was performed at a League meeting in November 1887. The play was about socialists on trial before a corrupt judge. It ended with the prisoners being freed by a workers' revolution. In June 1889, Morris went to Paris as the League's representative to the International Socialist Working Men's Congress. His international standing was recognized when he was chosen as the English spokesman. The Second International was formed from this Congress.

At the League's Fourth Conference in May 1888, disagreements grew. There were Morris's anti-parliamentary socialists, parliamentary socialists, and anarchists. The Bloomsbury Branch was expelled for supporting parliamentary action. The League's anarchist group, led by Charles Mowbray, grew stronger. They wanted the League to use violence to overthrow capitalism. By autumn 1889, the anarchists controlled the League's executive committee. Morris was removed as editor of Commonweal and replaced by the anarchist Frank Kitz. This made Morris feel distant from the League. It had also become a financial burden for him, as he had been giving it £500 a year. By autumn 1890, Morris left the Socialist League. His Hammersmith branch became the independent Hammersmith Socialist Society in November 1890.

Kelmscott Press & Final Years: 1889–1896

Morris & Co. continued its work in Morris's final years. They produced many stained glass windows designed by Burne-Jones. They also made six large tapestry panels showing the quest for the Holy Grail for Stanmore Hall, Shropshire.

Morris's influence on Britain's art world became clear. The Art Workers' Guild was founded in 1884. Morris was too busy with socialism to pay attention at first. But he was elected to the Guild in 1888 and became its master in 1892. Morris also initially did not support the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society. But he changed his mind after their first successful exhibit in October 1888. He gave lectures on tapestries for the group. In 1892, he was elected president. At this time, Morris focused again on preserving old buildings. He championed places like St. Mary's Church in Oxford, Blythburgh Church in Suffolk, Peterborough Cathedral, and Rouen Cathedral.

Although his socialist activism slowed down, he remained involved with the Hammersmith Socialist Society. In October 1891, he oversaw a short-lived newsletter, the Hammersmith Socialist Record. He began to oppose divisions within the socialist movement. He tried to rebuild his relationship with the SDF. He gave guest lectures at their events. He supported SDF candidate George Lansbury in a by-election in February 1894. In 1893, the Hammersmith Socialist Society helped create the Joint Committee of Socialist Bodies. Morris helped write its "Manifesto of English Socialists." He supported left-wing activists on trial, even if he disagreed with their violent methods. He also started using the term "communism" for the first time. He said, "Communism is in fact the completion of Socialism." In December 1895, he gave his last outdoor speech at Stepniak's funeral. He spoke alongside Eleanor Marx and Keir Hardie. Free from internal conflicts, he worked for socialist unity. He gave his last public lecture in January 1896 on "One Socialist Party."

In December 1888, the Chiswick Press published Morris's The House of the Wolfings. This was a fantasy story set in Iron Age Europe. It showed the lives of Germanic tribes. It had both prose and poetry. A sequel, The Roots of the Mountains, followed in 1889. Over the next few years, he published more poetic works. These included The Story of the Glittering Plain (1890) and The Well at the World's End (1896). He also translated the Anglo-Saxon tale, Beowulf. Because he did not fully understand Old English, his translation relied on one by Alfred John Wyatt. When published, Morris's Beowulf was criticized. After Alfred, Lord Tennyson died in October 1892, Morris was offered the position of Poet Laureate. He turned it down because he disliked its ties to the monarchy. The position went to Alfred Austin.

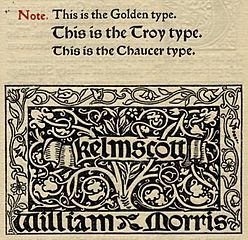

In January 1891, Morris founded the Kelmscott Press. This private press later published the famous Kelmscott Chaucer.

By the early 1890s, Morris was increasingly ill. He suffered from gout and showed signs of epilepsy. In August 1891, he took his daughter Jenny on a tour of Northern France to visit Medieval churches. Back in England, he spent more time at Kelmscott Manor. He sought treatment from doctor William Broadbent. He was prescribed a holiday in Folkestone. In December 1894, he was very sad when his mother died at age 90. In July 1896, he went on a cruise to Norway with engineer John Carruthers. His health worsened during the trip, and he had hallucinations. Returning to Kelmscott House, he became very ill. Friends and family visited him. He died of tuberculosis on October 4, 1896. Newspapers at the time mostly remembered him as a poet. They downplayed his involvement in socialism. However, socialist newspapers focused on his political work. His funeral was on October 6. He was buried in the churchyard of St. George's Church in Kelmscott.

William Morris's Personal Life

Morris's biographer E. P. Thompson described him as having a "robust bearing" and a "slight roll in his walk." He also had a "rough beard" and "disordered hair." The author Henry James said Morris was "short, burly, corpulent, very careless and unfinished in his dress." He had a "loud voice and a nervous restless manner." His talk was "wonderfully to the point and remarkable for clear good sense." Morris's first biographer Mackail called him "a typical Englishman" and "a typical Londoner of the middle class." But his genius made him "something quite individual." MacCarthy described Morris's lifestyle as "late Victorian, mildly bohemian, but bourgeois." Mackail noted he had traits of the middle class: "industrious, honest, fair-minded... but unexpansive and unsympathetic." Although he generally disliked children, Morris was very responsible toward his family. Mackail thought he "was interested in things much more than in people." He had "lasting friendships" but did not let people "penetrate to the central part of him."

Politically, Morris was a strong revolutionary socialist and anti-imperialist. Though raised Christian, he became an atheist. He rejected state socialism and large central control. He preferred local administration in a socialist society. Later, political activist Derek Wall suggested Morris could be called an ecosocialist. Morris was greatly influenced by Romanticism. Thompson said Romanticism was "bred into his bones." Thompson argued this "Romantic Revolt" was a "passionate protest against an intolerable social reality"—Victorian industrial capitalism. He believed Morris became "a realist and a revolutionary" only when he adopted socialism in 1882. Mackail thought Morris had an "innate Socialism" that "penetrated and dominated all he did." Given the conflict between his personal life and political views, MacCarthy called Morris "a conservative radical."

Morris's behavior was sometimes unpredictable. He was nervous and relied on male friends to help him. Morris's friends nicknamed him "Topsy" after a character in Uncle Tom's Cabin. He had a strong temper. When very angry, he could have seizures and blackouts. Rossetti sometimes teased Morris to make him angry for fun. Biographer Fiona MacCarthy suggests Morris might have had a form of Tourette's syndrome because he showed some symptoms. Later in life, he suffered from gout, a common problem for middle-class Victorian men. Morris believed one should "have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful." He also thought, "No work which cannot be done with pleasure in the doing is worth doing." His motto was "As I can," from the 15th-century painter Jan van Eyck.

William Morris's Work

Literature

William Morris wrote a lot of poetry, fiction, essays, and translations of old texts. His first poems were published when he was 24. He was still working on his last novel, The Sundering Flood, when he died. His daughter May's collection of his Collected Works (1910–1915) fills 24 volumes.

Morris started publishing poems and short stories in 1856 in The Oxford and Cambridge Magazine. He founded and paid for this magazine while at university. His first book, The Defence of Guenevere and Other Poems (1858), was the first book of Pre-Raphaelite poetry. Critics did not like the dark poems, which were set in a world of violence. This discouraged him from publishing more for several years. "The Haystack in the Floods" from that collection is now one of his more famous poems. It is a realistic story set during the Hundred Years' War. It shows the sad parting of lovers in a rainy countryside. An early Christmas poem was "Masters in this Hall" (1860). Another was "The Snow in the Street," from The Earthly Paradise.

Morris met Eiríkur Magnússon in 1868 and began learning Icelandic from him. Morris published translations of The Saga of Gunnlaug Worm-Tongue and Grettis Saga in 1869. He also published Story of the Volsungs and Niblungs in 1870. Another book, Three Northern Love Stories, came out in 1873.

In his last nine years, Morris wrote a series of imaginative stories called "prose romances." These novels, like The Wood Beyond the World and The Well at the World's End, are important in the history of fantasy fiction. Other writers wrote about foreign lands or dreams, but Morris's works were the first set in a completely made-up fantasy world. He tried to bring back the style of medieval romance. He wrote them in a way that copied medieval prose. Morris's writing style in these novels has been praised. Edward James called them "among the most lyrical and enchanting fantasies in the English language."

However, some, like L. Sprague de Camp, felt Morris's fantasies were not completely successful. This was partly because Morris avoided many writing techniques from later times. De Camp argued that the plots relied too much on coincidence. Still, many types of fantasy writing have come from the romance genre, indirectly influenced by William Morris.

Early fantasy writers like Lord Dunsany knew Morris's romances. The Wood Beyond the World greatly influenced C. S. Lewis's Narnia series. J. R. R. Tolkien was inspired by Morris's descriptions of early Germanic life in The House of the Wolfings. Tolkien felt much of his own writing was inspired by reading Morris early on. He even suggested he could not improve on Morris's work. Names like "Gandolf" and the horse Silverfax appear in The Well at the World's End.

Sir Henry Newbolt's medieval allegorical novel Aladore was influenced by Morris's fantasies. James Joyce also found inspiration in his work.

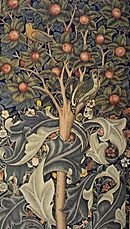

Textile Design

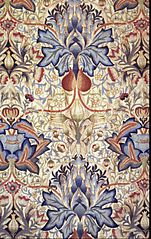

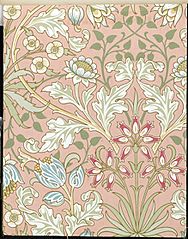

During his life, Morris created items in many crafts. He mainly focused on home furnishings. He made over 600 designs for wallpaper, textiles, and embroideries. He also created over 150 designs for stained glass windows. He designed three typefaces and about 650 borders for the Kelmscott Press. He believed that designing and making an item should not be separate. He thought that creators should be designer-craftsmen. This meant they would both design and make their goods. In textile design, Morris brought back several old techniques. He insisted on using good quality raw materials, mostly natural dyes, and hand processing. He also studied nature to get ideas for his designs. He learned how to make things before he designed them.

Mackail said Morris became a manufacturer not to make money, but to make the things he loved. Morris & Co.'s designs were popular among Britain's wealthy classes. Biographer Fiona MacCarthy said they became "the safe choice of the intellectual classes." The company's unique strength was the variety of items it produced. It also emphasized artistic control over production.

Morris's love for medieval textiles likely grew during his time with G. E. Street. Street had written a book on Ecclesiastical Embroidery in 1848. He strongly supported using more expressive embroidery techniques. These were based on Opus Anglicanum, a popular technique in medieval England.

Morris also liked hand-knotted Persian carpets. He advised the South Kensington Museum on buying fine Kerman carpets.

Morris taught himself embroidery. He worked with wool on a special frame. Once he learned the skill, he trained his wife Jane and her sister Bessie Burden. They made designs to his instructions. Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. sold "embroideries of all kinds." Church embroidery became an important part of their business for many years. By the 1870s, the firm offered both embroidery patterns and finished pieces. Morris helped lead the movement to bring back original and skilled embroidery. He was one of the first designers linked to the Royal School of Art Needlework. This school aimed to "restore Ornamental Needlework for secular purposes to the high place it once held."

Morris learned the practical art of dyeing for his business. He spent much time at Staffordshire dye works. He mastered dyeing processes and experimented with old or new methods. One result was bringing back indigo dyeing. He also renewed the use of vegetable dyes, like red from madder. These had been replaced by anilines. Dyeing wools, silks, and cottons was necessary for his goal. He wanted to produce the best woven and printed fabrics. After much work at the dye-vat (1875–1876), he focused on making textiles (1877–1878). He especially worked on bringing back carpet-weaving as a fine art.

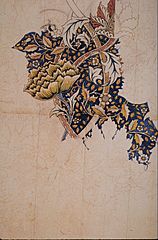

Morris's patterns for woven textiles included complex double-woven fabrics. These used two sets of warps and wefts. They created rich colors and textures. Morris dreamed of weaving tapestries in the medieval way. He called it "the noblest of the weaving arts." In September 1879, he finished his first solo tapestry, "Cabbage and Vine."

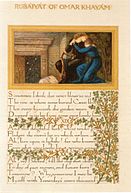

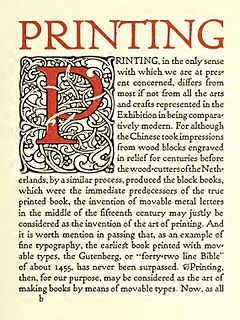

Book Illustration & Design

Art movements in the 19th and 20th centuries became interested in typographic arts. This greatly improved book design and illustration. Morris's designs, like those of the Pre-Raphaelite painters, often used medieval patterns. In 1891, he founded the Kelmscott Press. By 1898, it had produced over fifty works. It used traditional printing methods, a hand-driven press, and handmade paper. His masterpiece was an edition of the Works of Geoffrey Chaucer. It had illustrations by Edward Burne-Jones. Morris invented three unique typefaces: Golden, Troy, and Chaucer. The text was surrounded by detailed floral borders, like old illuminated manuscripts. His work inspired many small private presses in the next century.

Morris's artistic and social values were a main force in the Arts and Crafts Movement. The Kelmscott Press influenced many fine presses in England and the United States. It showed the importance of books as beautiful objects, not just words.

At Kelmscott Press, Morris closely supervised and helped with book-making. He wanted to create perfect works. He aimed to bring back the beauty of illuminated letters, rich gilding, and graceful bindings. He wanted to make a book that was better than any before. Morris designed his typefaces after the best early printers. He called his "golden type" after Jenson and others. He also carefully chose his paper to match the subject. Because of this, only wealthy people could buy his lavish books. Morris realized that making things in the medieval way was hard in a profit-driven society.

William Morris's Legacy

Hans Brill, President of the William Morris Society, called Morris "one of the outstanding figures of the nineteenth century." Linda Parry called him the "single most important figure in British textile production." When Morris died, his poetry was known worldwide. His company's products were found everywhere. In his lifetime, he was best known as a poet. But by the late 20th century, he was mostly known as a designer of wallpapers and fabrics.

He greatly helped bring back traditional British textile arts and production methods. Morris's ideas about production influenced the Bauhaus movement. Another part of Morris's preservation work was protecting nature from pollution and industrialism. Some historians of the green movement see Morris as an important early figure in modern environmentalism.

Aymer Vallance wrote the first biography of Morris, published in 1897, after Morris's death. This book presented the creation of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings as Morris's greatest achievement. Morris's next biographer was Burne-Jones's son-in-law John William Mackail. His two-volume Life of William Morris (1899) showed a kind picture of Morris. It mostly left out his political activities, treating them as a short phase.

MacCarthy's biography, William Morris: A Life for Our Time, was first published in 1994. A paperback edition came out in 2010. For the 2013 Venice Biennale, artist Jeremy Deller created a large mural about Morris. It was called "We Sit Starving Amidst our Gold." It showed Morris returning from the dead to throw a billionaire's yacht into the ocean.

MacCarthy organized the "Anarchy & Beauty" exhibition in 2014. It celebrated Morris's legacy at the National Portrait Gallery. About 70 artists were chosen for it. They had to pass a test about Morris's News from Nowhere.

The "Anarchy & Beauty" exhibition had an arts and crafts section. It featured Morris's own copy of Karl Marx's Das Kapital. It was hand-bound in gold-tooled leather. MacCarthy called it "the ultimate example of Morris's conviction that perfectionism of design and craftsmanship should be available to everyone."

Notable Collections & House Museums

Many galleries and museums have important collections of Morris's work. The William Morris Gallery in Walthamstow, England, is a public museum about his life and influence. The William Morris Society is based at Morris's last London home, Kelmscott House, Hammersmith. It is an international society, museum, and venue for events. The Art Gallery of South Australia has "the most comprehensive collection of Morris & Co. furnishings outside Britain." This collection includes books, embroideries, tapestries, fabrics, wallpapers, drawings, furniture, and stained glass.

The former "green dining room" at the Victoria and Albert Museum is now its "Morris Room." The V&A's British Galleries have other decorative works by Morris and his friends.

One meeting room in the Oxford Union is named the Morris Room. It is decorated with wallpaper in his style.

Wightwick Manor in the West Midlands, England, is a great example of the Morris & Co. style. It has many original Morris wallpapers, fabrics, carpets, and furniture. It also has May Morris art and Pre-Raphaelite artworks. The National Trust manages it. Standen in West Sussex, England, was designed by Webb between 1892 and 1894. It is decorated with Morris carpets, fabrics, and wallpapers. The illustrator Edward Linley Sambourne decorated his London home, 18 Stafford Terrace, with many Morris & Co wallpapers. These have been preserved. Morris's homes Red House and Kelmscott Manor have also been preserved. The National Trust bought Red House in 2003, and it is open to the public. The Society of Antiquaries of London owns Kelmscott Manor, and it is also open to the public.

The Huntington Library, Art Collections and Botanical Gardens in San Marino, California, bought a collection of Morris materials in 1999. It includes stained glass, wallpaper, textiles, embroidery, drawings, ceramics, over 2000 books, and the archives of Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. and Morris & Co. These materials were used for exhibitions in 2002 and 2003.

A Greater London Council blue plaque at Red House honors Morris and architect Philip Webb.

7, Hammersmith Terrace was the home of Sir Emery Walker, a close friend of Morris. The house is decorated in the Arts & Crafts style. It has many Morris wallpapers, furniture, and textiles. The Emery Walker Trust runs it, and it is open for tours.

In 2013, the Cary Graphic Arts Collection at Rochester Institute of Technology bought William Morris's printing press for $233,000. This press was specially strengthened to print Morris's Chaucer in 1896.

William Morris's Literary Works

Source:William Morris Archive. Morris's literary works, translations, life and images, the Book Arts

Collected Poetry, Fiction, and Essays

- The Hollow Land (1856)

- The Defence of Guenevere, and other Poems (1858)

- The Life and Death of Jason (1867)

- The Earthly Paradise (1868–1870)

- A Book of Verse (1870)

- Love is Enough, or The Freeing of Pharamond: A Morality (1872)

- The Story of Sigurd the Volsung and the Fall of the Niblungs (1877)

- Hopes and Fears For Art (1882)

- The Pilgrims of Hope (1885)

- A Dream of John Ball (1888)

- Signs of Change (1888)

- A Tale of the House of the Wolfings, and All the Kindreds of the Mark Written in Prose and in Verse (1889)

- The Roots of the Mountains (1889)

- News from Nowhere (or, An Epoch of Rest) (1890)

- The Story of the Glittering Plain (1891)

- Poems By the Way (1891)

- Socialism: Its Growth and Outcome (1893) (with E. Belfort Bax)

- The Wood Beyond the World (1894)

- Child Christopher and Goldilind the Fair (1895)

- The Well at the World's End (1896)

- The Water of the Wondrous Isles (1897)

- The Sundering Flood (1897) (published after his death)

- A King's Lesson (1901)

- The World of Romance (1906)

- Chants for Socialists (1935)

- Golden Wings and Other Stories (1976)

Translations

- Grettis Saga: The Story of Grettir the Strong with Eiríkur Magnússon (1869)

- The Story of Gunnlaug the Worm-tongue and Raven the Skald with Eiríkur Magnússon (1869)

- The Völsunga Saga: The Story of the Volsungs and Niblungs, with Certain Songs from the Elder Edda with Eiríkur Magnússon(1870) (from the Volsunga saga)

- Three Northern Love Stories, and Other Tales with Eiríkur Magnússon (1875)

- The Aeneids of Virgil Done into English (1876)

- The Odyssey of Homer Done into English Verse (1887)

- Of King Florus and the Fair Jehane (1893)

- The Tale of Beowulf Done out of the Old English Tongue (1895)

- Old French Romances Done into English (1896)

Morris's Beowulf was one of the first translations of the Old English poem into modern English.

| Old English verse | Morris's translation |

|---|---|

| Ðá cóm of móre under misthleoþum | Came then from the moor-land, all under the mist-bents, |

| Grendel gongan· godes yrre bær· | Grendel a-going there, bearing God's anger. |

| mynte se mánscaða manna cynnes | The scather the ill one was minded of mankind |

| sumne besyrwan in sele þám héan· | To have one in his toils from the high hall aloft. |

Published Lectures and Papers

- Lectures on Art delivered in support of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (Morris lecture on The Lesser Arts). London, Macmillan, 1882

- Architecture and History & Westminster Abbey. Papers read to the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings in 1884 and 1893. Printed at The Chiswick Press. London, Longmans, 1900

- Communism: a lecture London, Fabian Society, 1903

- Related: William Morris's Socialist Diary, ed. Florence Boos. 1st ed. Journeyman Press; Revised edition, Five Leaves Press, 2018.

Gallery

Morris & Co. Stained Glass

-

Burne-Jones-designed and Morris & Co.-executed Saint Cecilia window at Second Presbyterian Church (Chicago, Illinois)

-

Burne-Jones-designed and Morris & Co.-executed Luce Memorial Window in Malmesbury Abbey, Malmesbury, Wiltshire, England (1901).

Morris & Co. Patterns

-

Strawberry Thief, furnishing fabric, designed Morris, 1883

-

Detail of a watercolour design for the Little Flower carpet showing a portion of the central medallion, by William Morris

-

Panel of ceramic tiles designed by Morris and produced by William De Morgan, 1876

Kelmscott Press

See also

In Spanish: William Morris para niños

In Spanish: William Morris para niños

- Merry England

- Robert Steele – medievalist who was a disciple of Morris

- Simple living

- Sydney Cockerell – friend of Morris and secretary of Kelmscott Press

- Victorian decorative arts

- William Morris wallpaper designs

- List of works by the Kelmscott Press

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |