George Lansbury facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

George Lansbury

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait by Howard Coster, 1935

|

|

| In office 25 October 1932 – 8 October 1935 |

|

| Prime Minister | |

| Deputy | Clement Attlee |

| Preceded by | Arthur Henderson |

| Succeeded by | Clement Attlee |

| First Commissioner of Works | |

| In office 7 June 1929 – 24 August 1931 |

|

| Prime Minister | Ramsay MacDonald |

| Preceded by | Charles Vane-Tempest-Stewart |

| Succeeded by | Charles Vane-Tempest-Stewart |

| Chairman of the Labour Party | |

| In office 7 October 1927 – 5 October 1928 |

|

| Leader | Ramsay MacDonald |

| Preceded by | Frederick Roberts |

| Succeeded by | Herbert Morrison |

| Member of Parliament for Bow and Bromley |

|

| In office 15 November 1922 – 7 May 1940 |

|

| Preceded by | Reginald Blair |

| Succeeded by | Charles Key |

| In office 3 December 1910 – 26 November 1912 |

|

| Preceded by | Alfred Du Cros |

| Succeeded by | Reginald Blair |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 22 February 1859 Halesworth, Suffolk, England |

| Died | 7 May 1940 (aged 81) Manor House Hospital, North London, England |

| Political party | Labour |

| Spouse |

Bessie Brine

(m. 1880; died 1933) |

| Children | 12 (including Edgar and Daisy) |

| Relatives |

|

George Lansbury (born 22 February 1859 – died 7 May 1940) was a British politician. He was also a social reformer who led the Labour Party from 1932 to 1935. For most of his life, he fought against unfair systems and powerful groups. His main goals were to promote social justice, women's rights, and world peace by getting rid of weapons.

Lansbury started as a Liberal politician. In the early 1890s, he became a socialist. He then served his local community in the East End of London in many elected roles. His strong Christian beliefs guided him throughout his life. He was elected to Parliament in 1910. However, he gave up his seat in 1912 to fight for women's suffrage (the right for women to vote). He was even briefly put in prison for supporting protests.

In 1912, Lansbury helped start the Daily Herald newspaper and became its editor. During the First World War, the paper strongly supported peace. It also backed the October 1917 Russian Revolution. Because of these views, Lansbury was not elected to Parliament in 1918. He focused on local politics in his home area of Poplar. He went to prison with 30 other local leaders for his part in the Poplar "rates revolt" in 1921.

After returning to Parliament in 1922, Lansbury did not get a high-level job in the short Labour government of 1924. But he did serve as First Commissioner of Works in the Labour government of 1929–31. After a big political and economic crisis in 1931, Lansbury stayed with the Labour Party. He did not join the new government formed by his leader, Ramsay MacDonald. As the most senior Labour MP left after the 1931 election, Lansbury became the Leader of the Labour Party.

His belief in pacifism (opposing war) and his dislike of building up weapons went against his party's views. This was especially true as fascism grew in Europe. When his ideas were rejected at the 1935 Labour Party meeting, he resigned as leader. In his last years, he traveled through the United States and Europe, working for peace and disarmament.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Growing Up in the East End

George Lansbury was born in Halesworth, Suffolk, England, on 22 February 1859. He was the third of nine children. His father, also George Lansbury, worked on the railways. His family moved often, and their living conditions were simple. From his mother and grandmother, who had modern ideas, young George learned about important reformers like Gladstone. He also started reading the radical Reynolds's Newspaper. By the end of 1868, his family moved to the East End of London. This was the area where Lansbury would live and work for most of his life.

The East End in the 1860s and 1870s was a busy place. Its streets were often dirty and crowded. Lansbury went to schools in Bethnal Green and Whitechapel. He also worked many manual jobs. One job was loading and unloading coal wagons with his older brother, James. This was hard and dangerous work.

As a teenager, Lansbury often visited the House of Commons to listen to debates. He heard many of Gladstone's speeches. Gladstone's ideas about freedom and community deeply influenced young Lansbury.

George Lansbury senior died in 1875. That year, young George met Elizabeth Brine, who was 14. Her father owned a local sawmill. George and Elizabeth married in 1880. Lansbury remained a strong Anglican (a type of Christian) throughout his life.

Journey to Australia

In 1881, Lansbury's first child, Bessie, was born. Another daughter, Annie, followed in 1882. Lansbury wanted a better life for his family. He decided they should move to Australia. An agent in London described Australia as a land of great chances, with work for everyone. Lansbury and Bessie saved money for the trip. In May 1884, they sailed with their children to Brisbane.

The journey was difficult, with illness and danger. When they arrived in July 1884, Lansbury found that there were too many workers and not enough jobs. His first job, breaking stone, was too hard. He then became a van driver but was fired for refusing to work on Sundays due to his beliefs. He then agreed to work on a farm, but the employer had lied about the living conditions.

For several months, the Lansbury family lived in very poor conditions. Eventually, Lansbury was able to leave the farm. Back in Brisbane, he worked at the new Brisbane cricket ground. He loved cricket but learned that "cricket watching was not a pleasure for workmen."

Lansbury sent letters home, telling the truth about life for immigrants. He wrote that many people could not find work. In May 1885, his father-in-law sent money for their return trip. The Lansbury family left Australia for good and went back to London.

Early Political Work

First Campaigns for Change

When he returned to London, Lansbury worked in his father-in-law's timber business. In his free time, he spoke out against the false promises made by agents who encouraged people to move to other countries. His speech at a conference in April 1886 impressed many. Soon after, the government created a new office to give accurate information to people wanting to emigrate.

Lansbury joined the Liberal Party after returning from Australia. He quickly became a local leader. His good campaigning skills were noticed by important Liberals. They encouraged him to run for Parliament himself. Lansbury said no. He needed to earn money for his family, as MPs were not paid then. Also, he was starting to believe his future was as a socialist, not just a Liberal. He continued to work for the Liberals while also starting a short-lived socialist magazine called Coming Times.

London County Council Elections, 1889

In 1888, Lansbury helped Jane Cobden in her election campaign. She was running for the new London County Council (LCC) as a Liberal. Cobden was an early supporter of women's right to vote. Lansbury advised her on issues important to the East End, like housing for the poor and fair working conditions. Both Jane Cobden and another woman, Margaret Sandhurst, were elected in January 1889. However, their victories were challenged. Sandhurst was stopped from serving because she was a woman. Cobden was later prevented from voting. Lansbury urged her to fight back, but she did not. A law to allow women to serve on county councils failed in 1891. Women did not get this right until 1907.

Lansbury was upset that his party did not strongly support women's rights. He also felt let down by their lack of support for an eight-hour workday. He realized that the Liberal Party would only go as far as rich business owners allowed. By 1892, Lansbury felt he no longer belonged with the Liberals. Most of his friends were now socialists. After helping a Liberal candidate win an election in July 1892, Lansbury left the Liberal Party. He then joined the Social Democratic Federation (SDF).

Becoming a Socialist Leader

Social Democratic Federation

Lansbury chose the SDF because he admired its founder, Henry Hyndman. Lansbury quickly became a very active speaker for the SDF. He traveled across Britain, giving speeches and supporting workers' protests. Around this time, Lansbury stopped being religious for a short while. He felt that local church leaders were not helping the poor enough.

In 1895, Lansbury ran for Parliament twice for the SDF. He lost badly both times. After these losses, Hyndman convinced Lansbury to leave his job at the sawmill. He became a full-time paid organizer for the SDF. He spoke about a revolution where working people would take power. However, Lansbury's time as an SDF organizer was short. In 1896, his father-in-law died, and Lansbury felt he needed to take over the sawmill. He returned home to Bow.

In the 1900 election, Lansbury ran against a Conservative candidate. His opposition to the Boer War made him unpopular at the time. He lost the election, but his results were seen as good. This was Lansbury's last big effort for the SDF. He became unhappy with Hyndman's inability to work with other socialist groups. Around 1903, he left the SDF and joined the Independent Labour Party (ILP). At this time, Lansbury also found his Christian faith again and rejoined the Anglican Church.

Helping the Poor: Poor Law Guardian

In April 1893, Lansbury was elected as a Poor Law guardian for Poplar. This meant he helped manage support for the poor. Instead of the usual harsh rules of the workhouse, Lansbury wanted to make it a place of help, not despair. He wanted to remove the shame of being poor. Lansbury was part of a small group of socialists who worked hard to get their ideas approved.

Helping poor children get an education was very important to Lansbury. He helped change a strict school into a proper place of learning. In 1897, Lansbury wrote his first paper about helping the poor. He believed that only by changing industry to help everyone, not just a few, could society solve its problems.

In 1903, Lansbury was also elected to the Poplar Borough Council. In 1904, he convinced a rich American, Joseph Fels, to buy a farm. This farm became a place where unemployed people from Poplar could find work. Fels also helped fund a larger project. These projects worked well at first. But after a Liberal government was elected in 1906, they were criticized. The new minister, John Burns, was against these "labour colonies." He said they wasted money and spoiled lazy people. An investigation found some problems, but Lansbury was cleared. He remained popular and was re-elected in 1907.

In 1905, Lansbury joined a Royal Commission on the Poor Laws. This group studied the laws for four years. Lansbury and another reformer, Beatrice Webb, argued that the Poor Laws should be completely removed. They wanted a new system with old age pensions, a minimum wage, and public works projects. Most of their ideas later became national policy. The Poor Laws were finally removed in 1929.

Becoming Nationally Known

Fighting for Women's Vote

In the January 1906 election, Lansbury ran as an independent socialist in Middlesbrough. He strongly supported "votes for women." This was his first campaign focused on women's rights since 1889. He got less than 9 percent of the vote. His campaign manager was Marion Coates Hansen, a leading supporter of women's suffrage. Through Hansen, Lansbury became a strong supporter of women's right to vote. He joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), a more active group, and became close with Emmeline Pankhurst and her family.

The Liberal government elected in 1906 did not seem interested in women's suffrage. In the January 1910 election, they lost their majority. They then needed the support of Labour members. To Lansbury's disappointment, Labour did not use this power to push for women's votes. Lansbury lost his election in Bow and Bromley in January 1910. However, another election was called in December 1910. This time, Lansbury won his seat in Bow and Bromley.

Lansbury found little support from his Labour colleagues in Parliament for women's suffrage. He called them "weak." In Parliament, he criticized the prime minister, H. H. Asquith, for the harsh treatment of imprisoned women's rights activists. He was temporarily suspended from the House for being "disorderly." In October 1912, Lansbury felt so strongly that he resigned his seat. He ran again in a special election in Bow and Bromley just on the issue of women's suffrage. He lost. The Labour MP Will Thorne said that no election could be won on just that one issue.

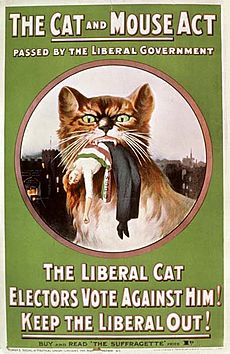

Out of Parliament, Lansbury spoke at a WSPU rally in April 1913. He openly supported strong actions: "Let them burn and destroy property." For this, Lansbury was charged with encouraging crime. He was found guilty and sentenced to three months in prison. He immediately went on a hunger strike and was released after four days. He was not arrested again, even though a law allowed it. In late 1913, Lansbury and his wife traveled to America and Canada. When he returned, he focused on the Daily Herald newspaper.

War, the Daily Herald, and Russia

The Daily Herald started as a temporary paper during a printers' strike. In April 1912, Lansbury and others raised money to relaunch it as a socialist daily newspaper. Famous writers contributed to the paper. Lansbury wrote regularly, especially supporting the women's suffrage movement. In early 1914, he became the paper's editor.

Before the First World War began in August 1914, the Herald strongly opposed the war. Lansbury blamed the war on capitalism. He said, "The workers of all countries have no quarrel." Lansbury's view was different from most of the Labour movement. During the war, the Herald became a weekly paper. It tried to give balanced news, without war fever. Lansbury visited the war trenches in 1914–15. He wrote about what he saw, and the paper supported calls for peace. It also supported people who refused to fight and Irish and Indian nationalists.

Lansbury used the Daily Herald to welcome the February 1917 revolution in Russia. He called it "a new star of hope." In March 1918, he praised the "Russian movement." When the war ended in November 1918, a quick election was called. People who had opposed the war, like Lansbury, were not popular. He failed to win back his seat.

The Herald became a daily paper again in March 1919. Under Lansbury, it strongly campaigned against Britain getting involved in the Russian Civil War. In February 1920, Lansbury traveled to Russia. He met Lenin and other Bolshevik leaders. He wrote a book about his trip. However, his visit was overshadowed by claims that the Herald was getting money from the Bolsheviks. Lansbury strongly denied this. But later, it was found that some of the claims were true, which caused problems for him and the paper. By 1922, the Herald had money problems. Lansbury resigned as editor and gave the paper to the Labour Party and the Trades Union Congress (TUC).

"Poplarism": The 1921 Rates Revolt

While campaigning nationally, Lansbury remained a local leader in Poplar. He was a borough councilor and a Poor Law guardian. From 1910 to 1913, he also served on the London County Council. In 1919, he became the first Labour mayor of Poplar. At that time, local councils were responsible for helping the poor in their own areas. This system was unfair to poorer areas like Poplar. They had low income from local taxes (rates) but high poverty and unemployment. Lansbury had long argued that taxes should be shared more fairly across London.

In March 1921, the Poplar Council decided not to pay certain taxes to other bodies. Instead, they used that money to help their own poor. This was against the law. On 29 July, the 30 councilors involved marched to the High Court. The judge told them they must pay the taxes. But the councilors refused. In early September, Lansbury and 29 other councilors were sent to prison. Among them were his son Edgar and Edgar's wife, Minnie.

The Poplar councilors' actions gained a lot of public interest and sympathy. The government was embarrassed. Other Labour councils threatened to do the same. After six weeks in prison, the councilors were released. A government meeting was held to solve the problem. This meeting led to a big win for Lansbury. A new law was passed that shared the cost of helping the poor more equally across all London areas. As a result, taxes in Poplar dropped by a third. The area gained an extra £400,000. Lansbury was seen as a hero. In the 1922 election, he won his parliamentary seat with a large majority. He held this seat for the rest of his life. The term "Poplarism" became known as a way for local governments to stand up for the poor against the central government.

In Parliament and Government

Labour Member of Parliament

In May 1923, the Conservative prime minister resigned. In December, a new election was called. The Conservatives lost their majority, and Labour became the second-largest party. King George V asked Labour's leader, Ramsay MacDonald, to form a government. Lansbury caused some upset by suggesting the King had tried to keep Labour out of power. Despite his experience, Lansbury was offered only a junior role in the new government, which he turned down. He believed the King had influenced this decision.

MacDonald's government lasted less than a year. In November 1924, the Liberals stopped supporting them. The December election brought the Conservatives back to power. Lansbury believed Labour's cause would continue to grow, no matter the election results. After the defeat, some suggested Lansbury should become the new party leader, but he refused. In 1925, he started and edited Lansbury's Labour Weekly. This paper shared his ideas about socialism, democracy, and peace. It later merged with another paper in 1927.

Lansbury continued his own campaigns in Parliament. He often clashed with Neville Chamberlain, the minister in charge of Poor Law reform. Lansbury called his department the "Ministry of Death." However, Lansbury's popularity within the Labour Party led to him being elected as the party's chairman (a mostly honorary role) in 1927–28. Lansbury also became president of an international group against imperialism. In 1928, he published his autobiography, My Life, which helped him financially.

Cabinet Minister, 1929–31

In the 1929 election, Labour became the largest party, but without a full majority. MacDonald formed another government, relying on Liberal support. Lansbury joined the new government as First Commissioner of Works. This job meant he was in charge of historic buildings, monuments, and royal parks. Even though it was seen as an easy job, Lansbury was very active. He improved public recreation areas. His most famous achievement was the Lido (a swimming area) on the Serpentine in Hyde Park. A round plaque in his memory can be seen on the Lido Bar and Cafe. Lansbury often met with the King for his duties. Surprisingly, they developed a friendly relationship.

MacDonald's second government faced a huge economic crisis after the Wall Street Crash in October 1929. Lansbury was part of a committee looking for solutions to unemployment. One idea was a large program of public works, but it was rejected due to cost. In July 1931, a committee suggested big cuts in government spending, including a large reduction in unemployment benefits.

In August, with financial panic growing, the government debated the report. MacDonald and others were ready to make the cuts. But Lansbury and nine other ministers refused to cut unemployment benefits. Because they were divided, the government could not continue. MacDonald then formed a new national government with other parties. Most Labour MPs, including Lansbury, were against this. MacDonald and his followers were expelled from the Labour Party. Arthur Henderson became the new Labour leader. In the October 1931 election, the new national government won by a huge amount. Labour was left with only 46 members. Lansbury was the only senior Labour leader to keep his seat.

Party Leader

Even though Labour lost badly in the election, Henderson remained the party leader. Lansbury led the small Labour group in Parliament. In October 1932, Henderson resigned, and Lansbury became the new leader. Historians generally agree that Lansbury led his small group in Parliament very well. He also inspired the discouraged Labour members. As leader, he started to improve the party's organization. These efforts led to many wins in local elections. For example, Labour gained control of the LCC in 1934. Lansbury "represented political hope and decency to the three million unemployed." During this time, Lansbury wrote his political book, My England (1934). In it, he described a future socialist country achieved through both big changes and gradual steps.

I believe that force never has and never will bring permanent peace and goodwill in the world ... God intends us to live peacefully and quietly with one another. If some people do not allow us to do so, I am ready to stand as the early Christians did, and say, this is our faith, this is where we stand, and, if necessary, this is where we will die.

The small Labour group in Parliament had little power over the economy. Lansbury's time as leader was mostly about foreign affairs and disarmament. The official party position was to work for peace through the League of Nations and to reduce weapons for all countries. Lansbury, supported by many Labour MPs, believed in Christian pacifism. He wanted Britain to get rid of its weapons even if other countries did not. He also wanted to dismantle the British Empire. Under his influence, the party's 1933 conference passed resolutions calling for "total disarmament of all nations." It also promised not to take part in war.

Pacifism became popular for a while. In February 1933, the Oxford Union voted that it would "in no circumstances fight for its King and Country." In October 1933, a Labour candidate who supported full disarmament easily won a special election. Lansbury sent a message saying, "I would close every recruiting station, disband the Army and disarm the Air Force... and say to the world: 'Do your worst'." In October 1934, the Peace Pledge Union was formed. Meanwhile, Adolf Hitler came to power in Germany and left international disarmament talks. Germany began to rearm.

As fascism and militarism grew in Europe, Lansbury's peaceful stance was criticized by trade unions in his party. They controlled most of the votes at party conferences. Walter Citrine, the TUC leader, said Lansbury thought the country should have no defense. The party's 1935 annual conference took place in October. Italy was about to invade Abyssinia. The party leaders proposed a resolution to put sanctions (penalties) on Italy. Lansbury opposed this, seeing it as a form of economic war. He gave a passionate speech about Christian pacifism. But then Ernest Bevin, a powerful union leader, spoke. Bevin criticized Lansbury for putting his personal beliefs before the party's policy to oppose fascist aggression. Union support ensured the sanctions resolution passed by a huge majority. Lansbury realized that a Christian pacifist could no longer lead the party. He resigned a few days later. His deputy, Clement Attlee, became the new leader. Lansbury never ran in a general election as party leader. As of 2021, he is the last Labour leader to step down without fighting a general election.

Later Years and Legacy

[Hitler] appeared free of personal ambition ... wasn't ashamed of his humble start in life ... lived in the country rather than the town ... was a bachelor who liked children and old people ... and was obviously lonely. I wished that I could have gone to Berchtesgaden and stayed with him for a little while. I felt that Christianity in its purest sense might have had a chance with him.

Lansbury was 76 when he resigned as Labour leader, but he did not stop working for public causes. In the November 1935 election, he kept his seat. Labour, now led by Attlee, increased its number of MPs. Lansbury focused entirely on world peace. In 1936, he traveled to the United States. He spoke to large crowds and met President Roosevelt to suggest a world peace conference. In 1937, he toured Europe, meeting leaders in Belgium, France, and Scandinavia. In April, he had a private meeting with Hitler. Lansbury's notes suggest Hitler was willing to join a world conference if Roosevelt called it. Later that year, Lansbury met Mussolini in Rome. Lansbury wrote several books about his peace journeys. His gentle and hopeful views of the European dictators were criticized as being too simple. Some British pacifists were upset he met Hitler. Lansbury continued to meet European leaders in 1938 and 1939. He was nominated for the 1940 Nobel Peace Prize, but did not win.

At home, Lansbury served a second term as Mayor of Poplar in 1936–37. He argued against direct fights with Mosley's Blackshirts during the October 1936 demonstrations, known as the Battle of Cable Street. In October 1937, he became president of the Peace Pledge Union. A year later, he welcomed the Munich Agreement as a step towards peace. During this time, he helped refugees from Nazi Germany. He chaired a fund that helped displaced Jewish children. On 3 September 1939, after war was declared with Germany, Lansbury spoke in the House of Commons. He said that the cause he had worked for his whole life was failing. But he hoped that from this terrible event, a spirit would rise that would make people stop relying on force.

In early 1940, Lansbury's health declined. He was suffering from stomach cancer. In an article published on 25 April 1940, he made a final statement of his Christian pacifism. He wrote, "I hold fast to the truth that this world is big enough for all, that we are all brethren, children of one Father." Lansbury died on 7 May 1940. His funeral was held at St Mary's Church, Bow, followed by cremation. His ashes were scattered at sea, as he wished. He wrote in his will, "I desire this because although I love England very dearly... I am a convinced internationalist."

Tributes and Lasting Impact

Most historians remember Lansbury for his strong character and beliefs, rather than just his political leadership.

Historian A. J. P. Taylor called Lansbury "the most lovable figure in modern politics." He was seen as a leading figure of the English socialist left in the 20th century. Other historians describe him as someone who protested for change, not just a politician seeking power. Journalists sometimes said Lansbury was too emotional. But his speeches in Parliament often included historical and literary references. He also wrote many books about socialist ideas.

Many agree that Lansbury was never selfish. His Christian socialist beliefs guided him to always help the poorest people. Historians believe that Lansbury was the best leader for the Labour Party after its political struggles in 1931. He was popular and inspired many Labour members. In the House of Commons, after Lansbury's death, Prime Minister Chamberlain said that while many did not agree with his ideas for peace, everyone recognized his strong beliefs and deep care for humanity. Clement Attlee also praised his former leader. He said Lansbury "hated cruelty, injustice and wrongs, and felt deeply for all who suffered... he was ever the champion of the weak."

After the Second World War, a stained glass window was placed in the Kingsley Hall community center in Bow to remember Lansbury. Streets and housing areas are named after him, like the Lansbury Estate in Poplar, built in 1951. Attlee suggested that Lansbury's lasting legacy is how his revolutionary ideas for social policies became accepted national policies just over ten years after his death.

His name and picture are on the plinth of the statue of Millicent Fawcett in Parliament Square, London. This statue, unveiled in 2018, honors supporters of women's suffrage.

Personal and Family Life

George Lansbury married Elizabeth Jane (Bessie) Brine on 22 May 1880 in Whitechapel, London. In May 1884, he took his wife and their three young children to Australia. They had hoped for a good life there, based on British government promises. But the reality was different, with little work and poor living conditions. By May 1885, they had enough and returned to London. Lansbury started working in his father-in-law's sawmill and began his political career by speaking about the harsh conditions in Australia.

For most of their married life, George and Bessie Lansbury lived in Bow. Their home became a "political haven" for anyone needing help. Bessie died in 1933. They had 12 children between 1881 and 1905.

Of their 10 children who lived to adulthood, Edgar followed his father into local politics. He became a Poplar councilor in 1912 and mayor in 1924–25. Edgar's daughter, Dame Angela Lansbury, born in 1925, became a famous stage and screen actress. George Lansbury's youngest daughter, Violet (1900–72), was active in the Communist Party. She lived and worked in Moscow for many years.

Another daughter, Dorothy (1890–1973), fought for women's rights. She married a Labour MP and was also a council member and mayor in Shoreditch. Dorothy's younger sister Daisy (1892–1971) worked as Lansbury's secretary for over 20 years. During the women's suffrage protests in 1913, Daisy Lansbury helped Sylvia Pankhurst escape the police by disguising herself as Pankhurst. In 1918, Daisy married the writer Raymond Postgate, who wrote George Lansbury's first biography. Their son Oliver Postgate created popular children's television shows.

The Lansbury family home was destroyed during the London Blitz in 1940–41. There is a small memorial stone for Lansbury in front of the current building, named George Lansbury House. There is also a memorial to Lansbury in the nearby Bow Church, where he was a long-time member and churchwarden.

|

See also

In Spanish: George Lansbury para niños

In Spanish: George Lansbury para niños