Neville Chamberlain facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Neville Chamberlain

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

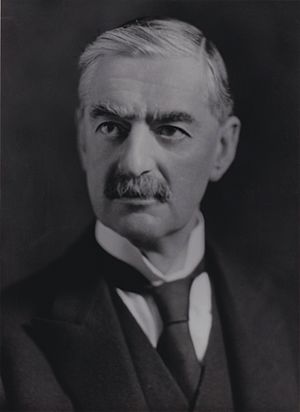

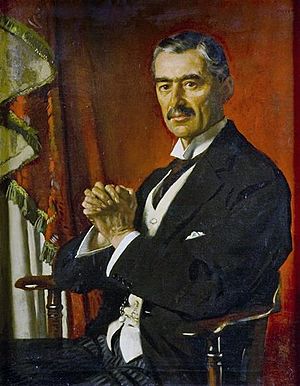

Chamberlain in 1936

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister of the United Kingdom | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 28 May 1937 – 10 May 1940 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | George VI | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Stanley Baldwin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Winston Churchill | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leader of the Conservative Party | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 27 May 1937 – 9 October 1940 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chairman | Douglas Hacking | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Stanley Baldwin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Winston Churchill | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Member of Parliament | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 14 December 1918 – 9 November 1940 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Constituency established | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Peter Bennett | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Constituency | Birmingham Ladywood (1918–1929) Birmingham Edgbaston (1929–1940) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born |

Arthur Neville Chamberlain

18 March 1869 Birmingham, England |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 9 November 1940 (aged 71) Heckfield, England |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Resting place | Westminster Abbey | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | Conservative | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other political affiliations |

Liberal Unionist Party | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse |

Anne de Vere Cole

(m. 1911) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Parents |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | Mason College | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Occupation |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (born 18 March 1869, died 9 November 1940) was a British politician. He served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940. He was also the Leader of the Conservative Party during this time.

Chamberlain is most remembered for his foreign policy called "appeasement." This policy aimed to avoid war by making concessions to aggressive countries. A key moment was the Munich Agreement in September 1938. Here, he agreed to let Nazi Germany, led by Adolf Hitler, take over the Sudetenland region of Czechoslovakia.

However, when Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, it started World War II. Chamberlain then announced that the United Kingdom was at war with Germany. He led the country for the first eight months of the war. He resigned in May 1940 and was replaced by Winston Churchill.

Before becoming Prime Minister, Chamberlain had a long career. He worked in business and local government. He became a Member of Parliament in 1918. He quickly rose through government ranks. He served as Minister of Health and Chancellor of the Exchequer. As Minister of Health, he introduced many reforms.

Historians still debate Chamberlain's legacy. Some criticize his appeasement policy. They believe it failed to stop Hitler. Others argue that Britain was not ready for war in 1938. They say his actions bought valuable time for the country to prepare.

Contents

- Early Life and First Steps in Politics

- Member of Parliament and Minister

- Chancellor of the Exchequer (1931–1937)

- Premiership (1937–1940)

- Lord President of the Council

- Death

- Legacy and Historical Views

- Honours

- See also

- Images for kids

Early Life and First Steps in Politics

Growing Up and Business Career

Neville Chamberlain was born in Birmingham, England, on 18 March 1869. His father, Joseph Chamberlain, was a well-known politician. He became the Mayor of Birmingham and a government minister. Neville's mother, Florence Kenrick, passed away when he was young. He had an older half-brother, Austen Chamberlain.

Neville was educated at home and later attended Rugby School. His father then sent him to Mason College, which is now the University of Birmingham. Neville wasn't very interested in his studies. In 1889, he started working for an accounting firm.

Later, his father sent him to the Bahamas to start a sisal plantation. Sisal is a plant used to make rope. Neville spent six years there, but the business was not successful. His father lost a lot of money on the project.

When he returned to England, Neville went into business. He bought a company called Hoskins & Company. They made metal beds for ships. He was the managing director for 17 years, and the company did well. He also became involved in local community work in Birmingham. For example, he helped found a committee for hospitals in 1906.

In 1911, at the age of 42, Neville married Anne Cole. She was a great support to him. She encouraged his interest in local politics. They had a son and a daughter together.

Entering Local Politics

Chamberlain didn't show much interest in politics at first. His father and half-brother were already in Parliament. In 1911, he successfully ran for a seat on the Birmingham City Council. He became chairman of the Town Planning Committee. Under his leadership, Birmingham created one of Britain's first city planning schemes.

In 1915, during the First World War, Chamberlain became the Lord Mayor of Birmingham. This was a very demanding job during wartime. He worked hard and expected the same from others.

In December 1916, Prime Minister David Lloyd George offered Chamberlain a new role. He was asked to be the Director of National Service. This job involved organizing people for war work. However, Chamberlain and Lloyd George often disagreed. Chamberlain resigned in August 1917. They disliked each other from then on.

Chamberlain decided to run for the House of Commons. He was elected in 1918 at the age of 49. This was quite old for someone to first become a Member of Parliament.

Member of Parliament and Minister

Rising Through Government Ranks

Chamberlain worked very hard in Parliament. He spent a lot of time on committees. He led a committee that looked into unhealthy living areas. He visited slums in many major British cities. In 1920, he was offered a job at the Ministry of Health. However, he refused to serve under Prime Minister Lloyd George.

In 1922, the Conservative Party chose a new leader, Bonar Law. Many senior politicians refused to work with Law. This opened the door for Chamberlain to rise quickly. In just ten months, he went from a regular Member of Parliament to Chancellor of the Exchequer.

Law first made Chamberlain Postmaster General. Then, in 1923, he became Minister of Health. Soon after, Law became very ill and resigned. Stanley Baldwin took over as Prime Minister. In August 1923, Baldwin promoted Chamberlain to Chancellor of the Exchequer.

Chamberlain was Chancellor for only five months. The Conservatives lost the 1923 election. Ramsay MacDonald became the first Labour Prime Minister. His government didn't last long, leading to another election in 1924. Chamberlain won his seat by a small number of votes. He then decided to run for a safer seat in Birmingham, which he held for the rest of his life.

Reforms as Minister of Health

When the Conservatives won the 1924 election, Chamberlain chose to return as Minister of Health. He had many ideas for new laws. In two weeks, he presented 25 proposals to the Cabinet. By the time he left office in 1929, 21 of these had become law.

One of his main goals was to change the Poor Law system. This system provided help to the poor. Chamberlain wanted to get rid of the elected boards that ran it. He believed these boards were not working well. In 1929, he introduced the Local Government Act 1929. This law successfully abolished the Poor Law boards.

Chamberlain generally had a difficult relationship with the Labour Party. He often disagreed with them. This tension would later play a role in his time as Prime Minister.

Chancellor of the Exchequer (1931–1937)

In 1929, Labour returned to power under Ramsay MacDonald. But in 1931, the government faced a big financial crisis. MacDonald formed a National Government with support from Conservatives. Chamberlain once again became Minister of Health.

After the 1931 election, the National Government won a huge victory. MacDonald then appointed Chamberlain as Chancellor of the Exchequer. Chamberlain proposed a 10% tax on foreign goods. He suggested lower or no taxes on goods from British colonies. This idea was similar to his father's "Imperial Preference" policy. The new law, the Import Duties Act 1932, passed easily.

Managing the Nation's Finances

Chamberlain presented his first budget in April 1932. He kept the strict spending cuts that the National Government had agreed upon. A major cost was the interest on war debts owed to the United States. Chamberlain managed to reduce the interest rate on most of Britain's war debt. Between 1932 and 1938, he cut the percentage of the budget spent on war debt interest in half.

In 1934, Chamberlain announced a budget surplus. This meant the government had more money than it spent. He was able to reverse some of the cuts made to unemployment benefits and civil servant salaries. He famously told Parliament, "We have now finished the story of Bleak House and are sitting down this afternoon to enjoy the first chapter of Great Expectations."

Social Welfare and Defence

Chamberlain also created the Unemployed Assistance Board (UAB) in 1934. He wanted to remove unemployment support from political arguments. He also saw the importance of providing activities for the many people who were unlikely to find work. The UAB became responsible for the "welfare" of the unemployed, not just their financial support.

In his early budgets, defence spending was cut significantly. However, by 1935, Germany was rearming under Hitler. Chamberlain became convinced that Britain needed to rearm too. He especially pushed for a stronger Royal Air Force. He understood that the English Channel would not protect Britain from air attacks.

In 1935, Stanley Baldwin became Prime Minister again. In the election that year, the National Government still won a large majority. During the campaign, some Labour leaders criticized Chamberlain for spending money on rearmament. They called it "scaremongering."

The Abdication Crisis

Chamberlain played an important role in the abdication crisis of 1936. King Edward VIII wanted to marry Wallis Simpson, an American woman who had been divorced twice. This was not acceptable to the government or the public.

Chamberlain believed Simpson was using the King for her own gain. He agreed with Baldwin that the King should step down if he married her. The King abdicated on 10 December 1936.

Soon after, Baldwin announced his retirement. On 28 May 1937, Chamberlain became Prime Minister.

Premiership (1937–1940)

Becoming Prime Minister

When Chamberlain became Prime Minister, he was 68 years old. Many people thought he would be a temporary leader. They expected him to step down for a younger politician later.

Chamberlain wanted to focus on domestic issues. He believed that settling European problems would allow him to do this. He also worked to improve how the government communicated with the press. He created a system to manage news and share information with journalists.

Domestic Policies and Reforms

Chamberlain saw himself as a reformer at home. He hoped to improve life for ordinary people.

One of his first achievements was the Factories Act 1937. This law improved working conditions in factories. It also limited the working hours for women and children. In 1938, Parliament passed the Coal Act 1938. This law allowed the government to take control of coal deposits.

Another important law was the Holidays with Pay Act 1938. This act suggested that employers give workers a week of paid holiday. It led to a big increase in holiday camps and leisure activities for working families. The Housing Act of 1938 provided money to clear slums and kept rent controls in place.

Improving Relations with Ireland

Relations between the UK and the Irish Free State had been difficult. This was due to disagreements over money and Ireland's desire for more independence. Chamberlain, who had been tough on Ireland as Chancellor, now sought a peaceful solution.

Talks began in November 1937. Ireland wanted to change its constitutional status and gain control of three naval bases, called Treaty Ports. Britain wanted to keep these ports, especially in wartime.

The negotiations were tough. In March 1938, Chamberlain made a final offer. It gave Ireland many of its demands. The agreements were signed in April 1938. Ireland agreed to pay £10 million to Britain. The issue of Northern Ireland's partition was not resolved. Chamberlain also accepted an oral promise that Britain could use the Treaty Ports if war broke out.

Winston Churchill criticized this agreement. He argued that giving up the Treaty Ports was dangerous. However, Chamberlain believed that friendly relations with Ireland were more important.

Foreign Policy and Appeasement

Early Efforts for Peace

Chamberlain wanted to make Germany a partner in a stable Europe. He believed Germany might be satisfied if some of its former colonies were returned. He hoped to reach a general agreement with Germany.

However, Germany was not eager to talk. Foreign Minister Konstantin von Neurath cancelled a visit to Britain in 1937. Later, Lord Halifax visited Germany privately and met Hitler. Both Chamberlain and the British Ambassador to Germany, Nevile Henderson, thought the visit was a success.

Chamberlain also started direct talks with Fascist Italy. Italy had invaded Ethiopia, making it unpopular internationally. Chamberlain hoped that improving relations with Italy would weaken the alliance between Italy and Germany. He even set up a private way to communicate with Italy's leader, Benito Mussolini.

In February 1938, Hitler began to pressure Austria to join Germany. This was called the Anschluss. Chamberlain believed it was important to strengthen ties with Italy. He hoped this would stop Hitler from taking over Austria. Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden disagreed with Chamberlain's approach. He felt Chamberlain was moving too fast. The Cabinet supported Chamberlain, and Eden resigned. Lord Halifax became the new Foreign Secretary.

The Road to Munich

In March 1938, Austria became part of Germany. Britain sent a strong protest note to Berlin. However, no military action was taken. Chamberlain told Parliament that Germany's methods were wrong.

After Austria, Hitler turned his attention to the Sudetenland region of Czechoslovakia. This area had many German-speaking people. Hitler demanded that this region join Germany. Britain had no military duty to Czechoslovakia. However, France and Czechoslovakia had a defence agreement.

The British government decided to urge Czechoslovakia to make a deal with Germany. Military leaders advised that Britain could do little to help Czechoslovakia if Germany invaded. Chamberlain told Parliament that he would not make firm commitments.

Britain and Italy signed an agreement in April 1938. Italy agreed to withdraw some troops from the Spanish Civil War. In return, Britain recognized Italy's conquest of Ethiopia. The French Prime Minister, Édouard Daladier, also agreed to follow Britain's approach to Czechoslovakia.

In May, tensions rose after an incident involving Sudeten Germans. Germany was rumored to be moving troops to the border. Prague responded by moving its own troops. The crisis seemed to calm down, and Chamberlain was praised. However, Germany had not planned an invasion at that time.

Negotiations between Czechoslovakia and the Sudeten Germans continued. But the Sudeten leader, Konrad Henlein, was secretly told by Hitler not to agree to anything. In August, Lord Runciman went to Prague as a British mediator. He met with leaders but made no progress.

Chamberlain knew Hitler would speak on 12 September. He prepared a plan to fly to Germany to negotiate directly with Hitler if war seemed likely.

September 1938: The Munich Agreement

Meetings Before the Conference

Lord Runciman continued to pressure the Czechoslovak government. After a small incident in Ostrava, Germany used it for propaganda. Runciman decided to pause negotiations until after Hitler's speech.

Tension was very high before Hitler's speech. Britain, France, and Czechoslovakia partly prepared their armies. Hitler spoke to his supporters, saying the Sudeten Germans were oppressed. He declared that Germany would not tolerate this any longer.

On 13 September, British intelligence reported that Germany planned to invade Czechoslovakia on 25 September. Convinced that France would not fight, Chamberlain decided to go to Germany. He sent a message to Hitler offering to negotiate. Hitler agreed.

Chamberlain flew to Germany on 15 September. This was his first time flying. He met Hitler at his retreat in Berchtesgaden. Hitler demanded that the Sudetenland be annexed by Germany. Chamberlain believed he had gained time for a peaceful solution. The French and Czechoslovaks reluctantly agreed to these demands.

Chamberlain flew back to Germany on 22 September to meet Hitler in Bad Godesberg. Hitler changed his demands, asking for immediate occupation of the Sudetenland. He also wanted Polish and Hungarian claims on Czechoslovakia to be addressed. Chamberlain strongly objected. He felt he had worked hard to get France and Czechoslovakia to agree to the earlier demands.

Hitler gave Chamberlain a five-page letter outlining his new demands. Chamberlain offered to mediate with the Czechoslovaks. Hitler then set a deadline of 1 October for the occupation. The meeting ended, and Chamberlain returned to London. He felt it was now up to the Czechs.

The Munich Conference

Hitler's new demands were met with resistance. War seemed unavoidable. Chamberlain made a radio address to the nation on 27 September. He said it was "horrible, fantastic, incredible" that people were preparing for war over a "quarrel in a far-away country."

On 28 September, Chamberlain asked Hitler for a summit meeting. He suggested a meeting with Britain, France, Germany, and Italy. Hitler agreed. News of this came as Chamberlain was speaking to Parliament. The House erupted in cheers.

On 29 September, Chamberlain flew to Munich for his third and final visit to Germany. He met with Daladier (France), Mussolini (Italy), and Hitler. Hitler stated his intention to invade Czechoslovakia on 1 October. Mussolini presented a proposal, which had actually been drafted by German officials.

The leaders discussed the agreement for hours. Chamberlain raised the issue of compensation for Czechoslovakia. Hitler refused. Late that evening, the "Munich Agreement" was ready for signing.

Chamberlain and Daladier informed the Czechoslovaks of the agreement. They urged them to accept it quickly. The Czechoslovak government reluctantly agreed to the terms.

The Path to War (October 1938 – August 1939)

After Munich, Chamberlain continued to rearm Britain. He told his Cabinet that it would be "madness" to stop rearming. He hoped the agreement with Hitler would lead to lasting peace. However, Hitler showed no public interest in further talks.

Some of Chamberlain's ministers, including Lord Halifax, began to doubt the appeasement policy. Public outrage over the Kristallnacht pogrom in Germany in November 1938 made any friendship with Hitler difficult.

Chamberlain still hoped for peace. In January 1939, he gave a speech expressing his desire for international peace. Hitler seemed to respond positively in a speech on 30 January. Chamberlain believed that Britain's stronger defences would bring Hitler to the negotiating table.

However, on 15 March 1939, Germany invaded the Czech provinces of Bohemia and Moravia. This included Prague. Chamberlain's initial response was weak. But within 48 hours, he spoke much more strongly against Germany. In a speech in Birmingham on 17 March, he warned that Hitler was trying to "dominate the world by force." He questioned if this was "the beginning of a new adventure." This speech was widely praised, and more people joined the armed forces.

Chamberlain then worked to create defence agreements with other European countries. He wanted to deter Hitler from further aggression. Britain and France guaranteed Poland's independence on 31 March 1939. This meant they would help Poland if it was attacked. Even Churchill and Lloyd George praised this decision.

The Prime Minister took other steps to prepare for war. He doubled the size of the Territorial Army. He created a new ministry to provide equipment for the armed forces. He also started peacetime conscription, meaning young men had to join the military. The Italian invasion of Albania in April 1939 led to guarantees for Greece and Romania. By September 1939, Britain's radar stations were fully operational.

Chamberlain was hesitant to form a military alliance with the Soviet Union. He distrusted Joseph Stalin. However, many in his Cabinet favored such an alliance. Talks with Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov dragged on for months. They failed in August 1939 because Poland and Romania refused to allow Soviet troops on their land.

A week after these talks failed, the Soviet Union and Germany signed the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. This agreement committed them not to attack each other. It also secretly divided Poland between them. Chamberlain dismissed the pact, saying it didn't change Britain's duties to Poland. On 23 August 1939, Chamberlain warned Hitler that Britain would stand by its promises to Poland. Hitler then ordered his generals to prepare for an invasion of Poland.

War Leader (1939–1940)

Declaring War

Germany invaded Poland on 1 September 1939. The British Cabinet warned Germany to withdraw its troops. Otherwise, the UK would fulfill its obligations to Poland. Chamberlain spoke to the House of Commons, blaming Hitler for the conflict.

No formal declaration of war was made immediately. France also needed time. The British Cabinet demanded that Hitler be given an ultimatum. If troops were not withdrawn by the end of 2 September, war would be declared. Chamberlain delayed the ultimatum's expiry. His statement to Parliament was not well received. Many feared he would seek another deal with Hitler.

Chamberlain's Cabinet met late that night. They decided the ultimatum would be given in Berlin the next morning. It would expire two hours later. At 11:15 AM on 3 September 1939, Chamberlain spoke to the nation by radio. He announced that the United Kingdom was at war with Germany.

He said, "I have to tell you now that no such undertaking has been received, and that consequently this country is at war with Germany." He expressed his sadness that his efforts for peace had failed. He stated that Hitler's actions showed he would only be stopped by force.

That afternoon, Chamberlain addressed Parliament. He spoke quietly, saying, "Everything that I have worked for, everything that I have hoped for, everything that I have believed in during my public life has crashed into ruins." He vowed to devote his strength to achieving victory.

The "Phoney War"

Chamberlain formed a War Cabinet. He invited the Labour and Liberal parties to join, but they declined. He brought Churchill back into the Cabinet as First Lord of the Admiralty. Churchill also had a seat in the War Cabinet.

The first months of the war saw little land action in the west. Journalists called it the "Phoney War." Chamberlain and most Allied leaders believed the war could be won by economic pressure and continued rearmament. Government spending increased, but not dramatically. Despite the challenges, Chamberlain's approval ratings remained high.

Downfall and Resignation

In early 1940, the Allies planned a naval campaign in Norway. They aimed to seize key ports and iron mines. However, Germany also planned to invade Norway. On 9 April, German troops invaded Denmark and Norway. German forces quickly took over much of Norway. Allied troops were sent but had little success. On 26 April, the War Cabinet ordered a withdrawal.

Chamberlain's opponents decided to challenge him in Parliament. A debate, known as the "Norway Debate," began on 7 May. Admiral of the Fleet Roger Keyes strongly criticized the Norway campaign. Leo Amery ended his speech by quoting Oliver Cromwell: "You have sat here too long for any good you are doing. Depart, I say, and let us have done with you. In the name of God, go!"

Labour called for a vote of confidence. Chamberlain asked his "friends" to support the government. The government won the vote, but its majority was greatly reduced. Many MPs, even those who voted against him, did not want Chamberlain to leave.

Chamberlain decided he would resign if the Labour Party would not join his government. Labour leader Clement Attlee refused to serve under Chamberlain. Chamberlain favored Halifax as the next Prime Minister. However, Halifax was reluctant. Churchill emerged as the choice.

On 10 May, Germany invaded the Low Countries. Chamberlain considered staying in office. But Attlee confirmed Labour would not serve under him. Chamberlain went to Buckingham Palace to resign. He advised the King to send for Churchill. Churchill later thanked Chamberlain for this advice.

In a radio broadcast that evening, Chamberlain told the nation, "For the hour has now come when we are to be put to the test... And you and I must rally behind our new leader, and with our united strength, and with unshakable courage fight, and work until this wild beast... has been finally disarmed and overthrown."

Lord President of the Council

Chamberlain did not issue any resignation honors. He remained leader of the Conservative Party. Many MPs still supported him. Churchill kept Chamberlain loyalists in government. Churchill wanted Chamberlain to return to the Exchequer, but he declined. He believed it would cause problems with the Labour Party.

Instead, Chamberlain accepted the post of Lord President of the Council. He had a seat in the small, five-member War Cabinet. When Chamberlain entered Parliament after his resignation, he received a huge ovation. Churchill, however, was received coolly.

Chamberlain felt deeply depressed after leaving power. He wrote, "Few men can have known such a reversal of fortune in so short a time." He missed Chequers, the Prime Minister's country residence. As Lord President, Chamberlain took on many responsibilities for domestic issues. He chaired the War Cabinet when Churchill was away. Attlee remembered him as a hardworking and fair chairman.

In May 1940, with France facing defeat, some suggested seeking a negotiated peace with Germany through Italy. Chamberlain helped persuade the War Cabinet to reject these negotiations.

Chamberlain worked to unite the Conservative Party behind Churchill. He helped overcome members' distrust of the new Prime Minister. Churchill, in turn, refused Labour and Liberal attempts to remove Chamberlain from the government.

In July 1940, a book called Guilty Men was published. It criticized the government for not preparing enough for war. It called for Chamberlain and other ministers to be removed. The book sold many copies and greatly damaged Chamberlain's reputation.

Chamberlain had always been healthy, but by July 1940, he was in constant pain. He had surgery and was diagnosed with terminal bowel cancer. The doctors kept this from him. He returned to work in mid-August but was too weak. He left London for the last time on 19 September.

Chamberlain offered his resignation to Churchill on 22 September 1940. Churchill was reluctant but accepted. Churchill asked if Chamberlain would accept the Order of the Garter, a high British honor. Chamberlain refused, saying he preferred to "die plain 'Mr Chamberlain' like my father before me."

Chamberlain was upset by the negative press comments about his retirement. The King and Queen visited him on 14 October. He received many supportive letters. He wrote to John Simon that he regretted nothing he had done. He was content to accept his fate.

Death

Neville Chamberlain died of bowel cancer on 9 November 1940, at age 71. His funeral service was held at Westminster Abbey five days later. Due to wartime security, the details were not widely announced. Churchill and Lord Halifax were among the pallbearers. His ashes were buried in the Abbey.

Churchill praised Chamberlain in the House of Commons after his death. He said Chamberlain acted with sincerity to save the world from war. Churchill also privately said he relied on Chamberlain to manage the home front. Other politicians also paid tribute to Chamberlain.

Legacy and Historical Views

A few days before his death, Chamberlain wrote that he was not worried about his reputation. He believed history would show that without Munich, the war would have been lost in 1938.

However, books like Guilty Men and Churchill's The Gathering Storm greatly damaged his reputation. Churchill portrayed Chamberlain as well-meaning but weak. He suggested Chamberlain was blind to Hitler's threat. Churchill argued that the delay between Munich and the war worsened Britain's position. For many years, few historians questioned Churchill's view.

Chamberlain's widow, Anne, felt that Churchill's work had many "omissions and assumptions."

In 1961, Iain Macleod wrote a biography of Chamberlain. This was the start of a new way of thinking about him. Historian A. J. P. Taylor argued that Chamberlain had prepared Britain adequately for defence. He called Munich "a triumph" for those who wanted peace.

In 1967, government papers from Chamberlain's time were released. These papers helped explain his actions. They showed that Chamberlain had considered a grand alliance against Germany. However, he rejected it, fearing it would make war more likely. The papers also revealed that military advisors believed Britain could not stop Germany from taking Czechoslovakia by force. These new findings led to a "revisionist" view of Chamberlain.

Later, a "post-revisionist" view emerged. Historians like R. A. C. Parker argued that Chamberlain had other choices. Parker suggested Chamberlain could have formed a strong alliance with France earlier. He believed Chamberlain's strong personality led Britain to choose appeasement.

Historian David Dutton noted that Chamberlain's reputation will always be linked to his policy towards Germany. He said, "Whatever else may be said of Chamberlain's public life his reputation will in the last resort depend upon assessments of this moment [Munich] and this policy [appeasement]."

Honours

Academic Honours

- Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) – 1938

- Oxford University – DCL

- University of Cambridge – LLD

- Birmingham University – LLD

- Bristol University – LLD

- Leeds University – LLD

- University of Reading – DLitt

Freedoms

- Honorary Freedom City of Birmingham

- Honorary Freedom City of London – conferred 1940 but died before acceptance, the scroll being presented to his widow in 1941

Honorary Military Appointments

- 1939: Honorary Air Commodore, No 916 (County of Warwick) Balloon Squadron, Auxiliary Air Force

See also

In Spanish: Neville Chamberlain para niños

In Spanish: Neville Chamberlain para niños

Images for kids

-

Chamberlain (right) as Lord Mayor of Birmingham in May 1916, alongside Prime Minister Billy Hughes of Australia

-

Chamberlain (centre, hat and umbrella in hands) walks with German foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop (right) as the Prime Minister leaves for home after the Berchtesgaden meeting, 16 September 1938. On the left is Alexander von Dörnberg.

-

From left to right, Chamberlain, Daladier, Hitler, Mussolini and Italian foreign minister Count Galeazzo Ciano as they prepare to sign the Munich Agreement

-

David Lloyd George, prime minister 1916–22, whose contempt for Chamberlain was reciprocated

-

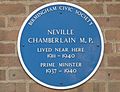

Blue plaque honouring Chamberlain, Edgbaston, Birmingham