William Orpen facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Sir

William Orpen

|

|

|---|---|

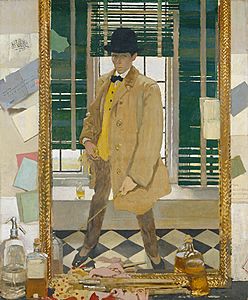

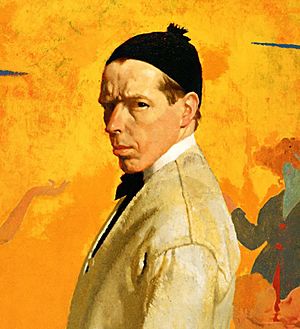

Orpen, self-portrait painting Sowing New Seed (1913) (Saint Louis Art Museum)

|

|

| Born |

William Newenham Montague Orpen

27 November 1878 Stillorgan, County Dublin, Ireland

|

| Died | 29 September 1931 (aged 52) London, England

|

| Resting place | Putney Vale Cemetery |

| Education |

|

| Known for | Portraits, War Art |

|

Notable work

|

The Refugee |

| Awards | KBE |

Sir William Newenham Montague Orpen (born November 27, 1878 – died September 29, 1931) was a famous Irish artist. He was known for his amazing drawings and popular portraits. Many rich people in the Edwardian era (early 1900s) wanted him to paint their pictures. However, some of his most interesting paintings are his self-portraits.

During World War I, Orpen became one of the most important official war artists for Britain. He was sent to the Western Front in France. There, he drew and painted soldiers, injured people, and German prisoners. He also painted portraits of important generals and politicians. He gave 138 of these artworks to the British government. They are now kept at the Imperial War Museum.

Orpen was able to stay in France longer than other war artists because he knew many high-ranking officers. He was even made a Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 1918. He also became a member of the Royal Academy of Arts. However, his time as a war artist affected his health and his standing in society. After he died, some critics did not like his work. For many years, his paintings were not often shown. This began to change in the 1980s.

Contents

William Orpen's Life Story

Early Years and Art Training

William Orpen was born in Stillorgan, County Dublin, Ireland. His father was a lawyer, and his mother was the daughter of a bishop. Both of his parents enjoyed painting as a hobby. His older brother, Richard Caulfield Orpen, became a well-known architect. William had a happy childhood in a large family home.

Orpen was a very talented painter from a young age. He started at the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art when he was almost 13. For six years, he won every major prize there. He even won a gold medal for drawing people. After that, he studied at the Slade School of Art in London from 1897 to 1899. At Slade, he became very good at oil painting. He also tried out new ways of painting.

Orpen often put mirrors in his paintings to create images within images. He sometimes added fake frames or collages around his subjects. He also included hints of other artists' works in his own paintings. In 1899, his large painting The Play Scene from Hamlet won a prize. His teachers at Slade helped him show his work in exhibitions. He became a member of the New English Art Club in 1900.

His painting The Mirror, shown in 1900, was inspired by older artworks. It used soft colors and deep shadows, like Dutch paintings from the 1600s. Orpen used the idea of a curved mirror in other paintings too. In 1901, he had his own art show in London.

While at Slade, he was engaged to Emily Scobel, who was a model for his painting The Mirror. They broke up in 1901. Orpen then married Grace Knewstub. They had three daughters together.

Starting His Art Career

After leaving art school, Orpen taught at the Chelsea Art School in London from 1903 to 1907. He ran it with another artist, Augustus John. Between 1902 and 1915, Orpen spent his time between London and Dublin. He also taught at the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art. His teaching helped many young Irish artists. Some of his students included Seán Keating and Grace Gifford.

During this time, Ireland was experiencing a "Celtic Revival." This was a time of new interest in Irish culture, literature, and art. Orpen painted three large symbolic paintings: Sowing New Seed, The Western Wedding, and The Holy Well. A key person in the Celtic Revival was Hugh Lane, who was Orpen's friend. Lane collected impressionist art with Orpen's help. In 1904, Orpen and Lane visited Paris and Madrid. Later, Lane asked Orpen to paint portraits of important Irish people for a gallery in Dublin.

From 1908 onwards, Orpen regularly showed his paintings at the Royal Academy. Between 1908 and 1912, Orpen and his family spent summers by the sea in Howth, Ireland. He started painting outdoors, which is called plein-air painting. He developed a special style using touches of color without clear outlines. His painting Midday on the Beach is a good example of this style.

Between 1911 and 1913, Orpen painted many portraits of Vera Brewster in London. These included The Roscommon Dragoon and The Angler. Another famous artist, John Singer Sargent, helped promote Orpen's work. Soon, Orpen became very successful at painting portraits for wealthy people in London and Dublin. His paintings like Mrs St. George (1912) and Lady Rocksavage (1913) show his skill at creating impressive "swagger portraits" that rich society loved.

Group portraits, called "conversation pieces," were also very popular. Orpen painted several, like The Cafe Royal in London (1912) and Homage to Manet (1909). The Homage to Manet painting showed other artists and critics sitting in front of a painting by Édouard Manet. By the start of World War I, Orpen was one of the most famous and successful artists in Britain.

William Orpen and World War One

When World War I began, many Irish people in England went back to Ireland to avoid being forced to join the army. Orpen's art assistant, Seán Keating, encouraged him to do the same. But Orpen decided to support the British war effort. In 1915, he joined the army and worked in an office in London.

Throughout 1916, Orpen continued painting portraits, including one of a sad Winston Churchill. But he soon used his connections to become a war artist. He knew important people like Philip Sassoon, who worked for Sir Douglas Haig, a top general. In January 1917, newspapers reported that Haig himself had made Orpen an official artist for the British Army in France. The government department in charge of war artists had to accept this.

Other war artists were usually low-ranking officers and could only visit the front lines for three weeks. But Orpen was promoted to major and allowed to stay at the front indefinitely. He even had a military helper, a car, and a driver. He also paid for his own assistant.

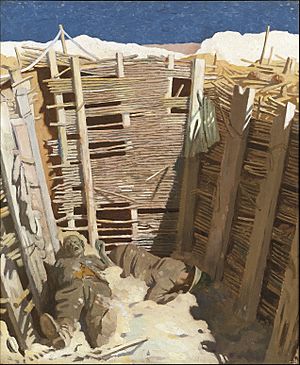

In April 1917, Orpen went to the Somme region in France. He stayed in Amiens. He arrived three weeks after German forces had moved back. Every day, Orpen was driven to places like Thiepval and Beaumont-Hamel. He sketched Allied troops and German prisoners. He also drew the terrible damage left by the Battle of the Somme in the cold, empty landscape.

Orpen did not send his work to the government or military censor at first. When he was told off, he had Haig's office move the officer who had complained. In May 1917, he painted portraits of General Haig and Sir Hugh Trenchard, who led the Royal Flying Corps. These pictures were printed in many British newspapers. In June, Orpen moved to the Ypres Salient area. He painted a self-portrait there called Ready to Start.

The Somme Battlefield Paintings

Orpen went back to the Somme in August 1917. He found the landscape had changed.

Orpen knew that this land was a huge graveyard. During the summer of 1917, only Orpen, his driver, and assistant were on the empty battlefield around Thiepval. The only other people were British and Allied groups burying the thousands of bodies left in the open or in old trenches.

On the Somme, Orpen worked hard to find new ways to paint the terrible situation. He stopped using soft shades and used new colors. He used a lot of light purples, mauves, and bright green. He also used large white areas to show the bright sunlight on the chalky ground, all under a strong blue sky.

After his successful portraits of Haig and Trenchard, Orpen was asked to paint pilots from the Royal Flying Corps. He visited airfields in September and October 1917. His portrait of Lieutenant Reginald Hoidge was painted just hours after the young pilot had been in a dogfight. Orpen was very impressed by how calm he was. Orpen's portrait of Arthur Rhys-Davids is also very clear with rich colors. Rhys-Davids was killed in battle within a week of sitting for Orpen. Orpen's portrait of him was used on the cover of a magazine and printed many times.

The Refugee Painting

In late 1917, Orpen was in the hospital for two weeks. There, he met a young Red Cross worker from Lille named Yvonne Aupicq. Orpen painted several portraits of her. He sent two of these to the official censor in early 1918. Orpen called both paintings A Spy. In March 1918, he was questioned by A. N. Lee, the military censor. Lee told him that if the person really was a spy, Orpen could face a court-martial (a military trial). Orpen later agreed to rename the two pictures The Refugee.

As the war went on, Orpen and Lee became good friends. Orpen painted two portraits of Lee. They wrote letters to each other until Orpen died. It is not clear how well known this friendship was. Lee had been the officer sent to Dublin to stop the 1916 Easter Rising. He was also in charge of arranging some of the executions after the fighting. One of these was Joseph Plunkett, who was married to Grace Gifford, Orpen's best student. In fact, from the time he joined the British Army in 1915 until his death in 1931, Orpen only spent one day in Ireland, in 1918.

In 2010, a third version of The Refugee appeared on a TV show. The Imperial War Museum had told its owner it was a copy. But an art expert on the show said it was painted by Orpen himself. It was a "thank-you" gift to Lord Beaverbrook for helping Orpen avoid the court-martial. The painting was estimated to be worth £250,000.

Orpen's War Art Recognition

In May 1918, 125 of Orpen's war paintings and drawings were shown at a gallery in London. The exhibition was very successful. Over 9,000 people paid to see it in four weeks. Some highlights were nine of Orpen's "khaki portraits" and works from the Somme like Highlander Passing a Grave. There was much talk in the newspapers about why the censor allowed Orpen's Dead Germans in a Trench to be shown. This was after he had refused to allow Christopher Nevinson's Paths of Glory to be displayed two months earlier.

Actually, Arthur Lee had refused almost all the paintings shown at the gallery. But Orpen appealed to a higher general and got the decision changed. After this London show, other museums wanted to host the exhibition. It went to the Manchester City Art Gallery and then to the United States. While the exhibition was in London, Orpen announced that he was giving all the displayed works to the British government. He wanted them to stay in their white frames and be kept together. They are now at the Imperial War Museum in London. That summer, the King made him a Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire.

Later War Paintings in 1918

Orpen went back to France in July 1918. He spent another summer painting on the old Somme battlefield. He also often visited Paris to finish portraits of Canadian commanders. Later, he painted the immediate aftermath of fighting at Zonnebeke. Orpen wanted to stay in France and work in the newly freed towns. By the end of summer 1918, Orpen was very tired mentally. His works became more dramatic and less realistic. In Harvest (1918), which shows women tending a grave with barbed wire, he used bright colors to show the unreal nature of the scene.

Towards the end of the war, Orpen painted a few "parable paintings." These used dark humor to imagine the coming victory. Most of these paintings were never shown to the public after the war. In November 1918, Orpen became very ill. Yvonne Aupicq nursed him for two months. He then moved to Paris in January 1919 for his next art job.

The Peace Conference Paintings

When the war ended, the Imperial War Museum asked Orpen to stay in France. He was to paint three large group portraits of the people attending the Paris Peace Conference. Throughout 1919, he painted individual portraits of the delegates. These became the basis for his two large paintings: A Peace Conference at the Quai d'Orsay and The Signing of Peace in the Hall of Mirrors. In both pictures, the grand buildings seem to overpower the politicians. Orpen felt that the politicians' arguments made them seem small.

Orpen believed the whole conference was not showing enough respect for the soldiers who suffered in the war. He tried to show this in his third painting. This picture was supposed to show the delegates entering the Hall of Mirrors to sign the Treaty of Versailles. Orpen had planned to put generals and other delegates in the painting. He also included two extra figures: a sergeant and Arthur Rhys-Davids, the young pilot he had painted before he was killed.

After working on this painting for nine months, Orpen painted over all the figures. He replaced them with a coffin covered by the Union Jack flag. On either side were two ghostly, ragged soldiers. Two angels above them held flower garlands. This painting, now called To the Unknown British Soldier in France, was first shown in 1923. The public voted it picture of the year. However, almost all art critics strongly disliked it. Some critics accused Orpen of bad taste and poor skill. Orpen did receive letters from former soldiers and families of those who died. He felt he needed to explain his painting and what he meant by it.

However, it was not the group portrait the Imperial War Museum had asked for. The Museum refused to accept it. The painting stayed in Orpen's studio until 1928. Then, he offered to paint out the angels and soldiers if that would make the Museum accept it. The Museum's director said he would be happy to accept the picture as it was. Orpen painted out the soldiers, and the Museum accepted the painting in 1928.

Later Life and Death

After the war, Orpen went back to painting portraits for wealthy people. He was very successful. He always had many portrait jobs. In the 1920s, he often earned a lot of money each year. He had homes and studios in both London and Paris.

Orpen's book about his war experiences, An Onlooker in France, 1917–1919, was published in 1921. All the money from the book went to charities for war victims. In 1923, Orpen was asked to paint a portrait of Edward, the Prince of Wales. There were many disagreements about this painting. The Prince's advisors wanted a formal portrait. But Orpen wanted to paint Edward in his golf clothes. Orpen got his way, but the painting was not shown until 1928.

In 1927, Orpen painted a portrait of David Lloyd George, a very important politician. But the painting was rejected because it was too informal. The painting stayed with Orpen and was bought by the National Portrait Gallery after he died. In 1928, Orpen tried to become President of the Royal Academy but lost. His art was also part of the painting event at the 1928 Summer Olympics.

Orpen became very ill in May 1931. He sometimes lost his memory. He died at age 52 in London on September 29, 1931. He was buried at Putney Vale Cemetery. A stone tablet in the Island of Ireland Peace Park in Belgium remembers him.

Orpen's Self-Portraits

Orpen painted many self-portraits during his life. He often showed himself in the act of painting. He also created many different images of himself. In 1908, he painted Self-portrait as Chardin, showing himself as the painter Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin at an easel. A year before, he had painted a self-portrait inspired by Chardin's 1776 work.

During World War I, Orpen painted at least three self-portraits. These ranged from the hopeful Ready to Start in June 1917 to more serious pictures a few months later. Bruce Arnold, who wrote about Orpen, said that his self-portraits were often deep and dramatic. They seemed to show a personal need for him to look closely at himself. He once painted himself as a jockey. In his painting The Dead Ptarmigan – a self-portrait, he looks grumpy while holding a dead bird.

Some people felt Orpen's later self-portraits were not as good. A writer named Kenneth McConkey said in 2005 that Orpen was emotionally exhausted after painting the war. He wrote that after the war, Orpen's portraits were done very quickly. He said Orpen's face in his later self-portraits looked like he was struggling inside.

-

Self-portrait with glasses, (1907), National Gallery of Australia

-

Leading the Life in the West, (c. 1910), Metropolitan Museum of Art

Orpen's Lasting Impact

After Orpen died, there were exhibitions of his work in New York in 1932 and in London in 1933. However, some artists and critics spoke badly about his work. For many years, Orpen was mostly forgotten. Besides his war paintings at the Imperial War Museum, only a few of his works were regularly shown in Britain.

A major show of his work was held in Ireland in 1978. But it was not shown in Britain. Bruce Arnold wrote a book about Orpen in 1981, which made scholars more interested in him. In 2005, a big exhibition of his work, including his peacetime art, was held at the Imperial War Museum. This led to people rethinking Orpen's importance in British and Irish culture.

Memberships and Awards

William Orpen was part of several important art groups:

- 1900: Member, New English Art Club

- 1904: Associate of Royal Hibernian Academy

- 1908: Member of Royal Hibernian Academy

- 1908: Member, National Portrait Society

- 1919: Associate of the Royal Academy

- 1921: Member of the Royal Academy

- 1921: President, International Society of Sculptors, Painters and Gravers

See also

In Spanish: William Orpen para niños

In Spanish: William Orpen para niños

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |