Icelandic language facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Icelandic |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| íslenska | ||||

| Native to | Iceland, Norway | |||

| Native speakers | 320,000 (2011) | |||

| Language family |

Indo-European

|

|||

| Writing system | Latin (Icelandic alphabet) Icelandic Braille |

|||

| Official status | ||||

| Official language in | ||||

| Regulated by | Árni Magnússon Institute for Icelandic Studies in an advisory capacity | |||

| Linguasphere | 52-AAA-aa | |||

|

||||

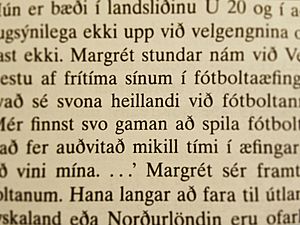

Icelandic is the official language of Iceland. It's a Germanic language, meaning it's related to languages like English and German. It comes from Old Norse, the language spoken by the Vikings.

Because Iceland is an island far from other countries, the language hasn't changed much over time. This means Icelandic people can still read texts written hundreds of years ago!

Icelandic uses four special letters not found in English:

- þ (thorn): Sounds like the 'th' in "thin".

- ð (edh): Sounds like the 'th' in "this". It's a softer sound than 'þ'.

- æ: Sounds like the 'i' in "ice".

- ö: Sounds like the 'u' in French words like "lune".

Some experts say there are only two main Nordic language groups: Eastern-Nordic and Western-Nordic. Icelandic and Faroese are in the Western-Nordic group because they are very similar. Many people also consider Icelandic one of the more challenging languages to learn!

Contents

A Look at Icelandic History

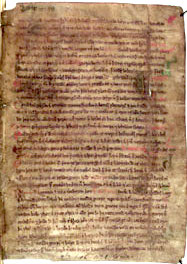

The oldest Icelandic writings we still have are from around 1100 AD. Many of these early texts were poems and laws. These were first passed down by speaking them, before being written.

The most famous old Icelandic texts are the sagas of Icelanders. These are historical stories and poems, including the Poetic Edda. The language in these sagas is called Old Icelandic. It's a western version of Old Norse.

Even when Denmark ruled Iceland (from 1536 to 1918), the Icelandic language didn't change much. People continued to use it every day. While it's older than other Germanic languages, Icelandic pronunciation did change between the 12th and 16th centuries.

How the Icelandic Alphabet Developed

The modern Icelandic alphabet we use today was mostly set in the 1800s. A Danish language expert named Rasmus Rask helped create this standard.

His work was based on an even older document from the 1100s. This document was written by an unknown author, now called the First Grammarian. Rask brought back old features, like the letter 'ð'. Later changes in the 1900s included using 'é' instead of 'je'. Also, the letter 'z' was replaced with 's' in 1973.

Even with some changes, written Icelandic has stayed very similar since the 11th century. Modern Icelanders can still understand the original sagas and Eddas. These texts were written about 800 years ago! People usually read them with updated spelling and notes, but the stories are mostly the same.

Learning Icelandic Words

Early Icelandic words came mostly from Old Norse. When Christianity came to Iceland in the 11th century, new words were needed. These new words often came from other Scandinavian languages. For example, kirkja means "church".

Other languages also influenced Icelandic. French gave words about courts and knights. Words for trade and business came from Low German.

In the late 1700s, people in Iceland started to protect their language. They wanted to keep it pure and avoid borrowing too many foreign words. This is called linguistic purism in Icelandic. Today, it's common to create new Icelandic words by combining existing Icelandic parts.

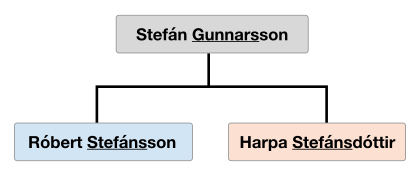

Icelandic Naming System

Icelandic personal names are unique! They are usually based on the child's father's name. This is called a patronymic system. Sometimes, they use the mother's name, which is called a matronymic system.

This is different from most Western countries that use family names passed down through generations. In Iceland, a person uses their father's (or mother's) name. They add -son (meaning "son") or -dóttir (meaning "daughter") to it. So, if a father's name is Jón, his son might be Jónsson and his daughter Jónsdóttir.

Understanding Icelandic Grammar

Icelandic grammar has many features from ancient Germanic languages. It's similar to old Norwegian before it lost some of its complex endings. Modern Icelandic is still a heavily inflected language. This means words change their endings depending on their role in a sentence.

Icelandic has four cases:

- Nominative

- Accusative

- Dative

- Genitive

Icelandic nouns can be masculine, feminine, or neuter. Nouns, adjectives, and pronouns all change their endings for these cases and for singular or plural forms.

How Verbs Work

Verbs in Icelandic change their form based on:

- Tense (like past, present, future)

- Mood (like telling someone to do something)

- Person (who is doing the action, like "I" or "they")

- Number (singular or plural)

- Voice (active or passive)

There are three voices: active, passive, and middle. The middle voice can sometimes change the meaning of a verb a lot! For example, koma means "come," but komast means "get there."

Most Icelandic verbs end with -a in their basic form (infinitive). For example, að vera means "to be."

Similarities with English Words

Since Icelandic and English both come from Germanic languages, they share many similar words. These words are called cognates. They have the same or a similar meaning and come from a common root.

For example, the way we show possession in English (adding -s to a noun, like "dog's") is similar in Icelandic. Over time, the spelling and pronunciation of these words have changed in both languages.

Here are a few examples:

| English word | Icelandic word |

|---|---|

| apple | epli |

| book | bók |

| high | hár |

| house | hús |

| mother | móðir |

| night | nótt |

| stone | steinn |

| that | það |

| word | orð |

See also

In Spanish: Idioma islandés para niños

In Spanish: Idioma islandés para niños