Friedrich Engels facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Friedrich Engels

|

|

|---|---|

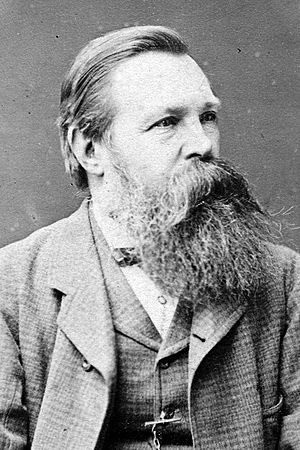

Engels in Brighton by William Hall, 1879

|

|

| Born | 28 November 1820 Barmen, Jülich-Cleves-Berg, Kingdom of Prussia, German Confederation

(part of modern Wuppertal, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany) |

| Died | 5 August 1895 (aged 74) London, England

|

| Nationality | German |

| Political party |

|

|

Philosophy career |

|

| Education | Gymnasium zu Elberfeld (withdrew) University of Berlin (no degree) |

|

Notable work

|

The Condition of the Working Class in England, Anti-Dühring, Socialism: Utopian and Scientific, The German Ideology |

| Partner(s) | Mary Burns (died 1863) |

| Era | 19th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Continental philosophy Marxism |

|

Main interests

|

Political philosophy, political economy, class struggle, criticism of capitalism |

|

Notable ideas

|

Alienation and exploitation of the worker, dialectical materialism, historical materialism, false consciousness |

|

Influenced

|

|

| Signature | |

|

|

Friedrich Engels (born November 28, 1820 – died August 5, 1895) was a German thinker, writer, and revolutionary. He was also a businessman and journalist. His father owned large textile factories in England and Germany.

Engels is best known for working with Karl Marx to create what is now called Marxism. In 1845, he wrote The Condition of the Working Class in England. This book was based on what he saw and learned in English cities. In 1848, Engels and Marx wrote The Communist Manifesto together. He also wrote and helped write many other important books.

Later, Engels gave Marx money so Marx could do his research and write his famous book, Das Kapital. After Marx died, Engels finished editing the second and third parts of Das Kapital. He also organized Marx's notes for a "fourth volume." In 1884, Engels published The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State. This book was based on Marx's studies of different cultures.

Engels passed away in London on August 5, 1895, at the age of 74. His ashes were scattered off Beachy Head in England.

Contents

Friedrich Engels's Life Story

His Early Years

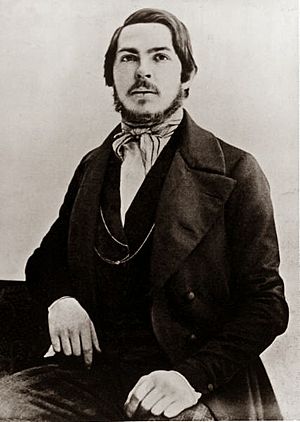

Friedrich Engels was born on November 28, 1820, in Barmen, Prussia. This area is now part of Wuppertal, Germany. He was the oldest son of Friedrich Engels Sr. and Elisabeth von Haar. His family was wealthy and owned large cotton factories in Barmen and Salford, England. His parents were very religious Protestants. They raised their children with strong religious beliefs.

When he was 13, Engels went to grammar school in Elberfeld. But at 17, his father made him leave school. His father wanted him to become a businessman. So, Engels started working as an apprentice in the family business. In 1838, his father sent him to work at a trading house in Bremen. His parents hoped he would follow in his father's footsteps. But Engels became interested in revolutionary ideas, which disappointed them.

While in Bremen, Engels started reading the ideas of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. Hegel's philosophy was very popular in Germany then. In 1838, Engels published his first poem. He also began writing newspaper articles. These articles criticized the problems caused by industrialization. He used the pen name "Friedrich Oswald" to keep his family out of trouble.

In 1841, Engels joined the Prussian Army for his military service. He was stationed in Berlin. There, he attended university lectures and met a group called the Young Hegelians. He wrote articles without his name on them for the Rheinische Zeitung newspaper. These articles showed the terrible working and living conditions of factory workers. Karl Marx was the editor of this newspaper. Engels did not meet Marx until late 1842. Engels later said that German philosophy greatly influenced his thinking. He also wrote in 1840: "To get the most out of life you must be active, you must live and you must have the courage to taste the thrill of being young."

Engels started to believe in atheism. This caused problems in his relationship with his parents.

Time in Manchester and Salford

In 1842, Engels was 22 years old. His parents sent him to Manchester, England. Manchester was a big manufacturing city where factories were growing fast. He was supposed to work in the offices of his family's company, Ermen and Engels. This company made sewing threads. Engels's father hoped that working in Manchester would change his son's radical ideas. On his way to Manchester, Engels visited the Rheinische Zeitung office in Cologne. There, he met Karl Marx for the first time. They didn't get along well at first. Marx thought Engels was still connected to the Young Hegelians, whom Marx had just stopped working with.

In Manchester, Engels met Mary Burns. She was a strong Irish woman with radical ideas. She worked in the Engels factory. They started a relationship that lasted 20 years until she died in 1863. They never married because both were against marriage. Engels believed in being loyal to one partner. But he thought that marriage, as set up by the state and church, was a form of unfair control. Mary Burns showed Engels around Manchester and Salford. She took him to the poorest areas for his research.

Between October and November 1843, Engels wrote his first critique of how money and goods were made. It was called "Outlines of a Critique of Political Economy." Engels sent this article to Paris. Marx published it in his newspaper, Deutsch–Französische Jahrbücher, in 1844.

Engels closely studied the slums of Manchester. He wrote down the terrible things he saw. These included child labour, pollution, and workers who were overworked and poor. He sent three articles to Marx. These were published in the Rheinische Zeitung and then in the Deutsch–Französische Jahrbücher. They described the lives of the working class in Manchester. He later put these articles into his first important book, The Condition of the Working Class in England (1845). He wrote the book between 1844 and 1845. It was published in German in 1845. In the book, Engels described the "grim future of capitalism." He wrote about the dirty and crowded places where working people lived. The book was published in English in 1887.

Engels kept writing and being involved in radical politics. He went to places where members of the English labour and Chartist movements met. He also wrote for several newspapers.

Moving to Paris

Engels decided to go back to Germany in 1844. On his way, he stopped in Paris to meet Karl Marx again. Marx had been living in Paris since 1843. This was after the Rheinische Zeitung newspaper was banned by the Prussian government. Before meeting Marx, Engels had already developed his own ideas about materialism and scientific socialism.

In Paris, Marx was publishing the Deutsch–Französische Jahrbücher. Engels met Marx for the second time on August 28, 1844. They quickly became close friends and stayed that way for their whole lives. Marx had read Engels's articles on The Condition of the Working Class in England. He was very impressed. Engels had written that a class that suffers all the bad parts of society without enjoying its good parts cannot be expected to respect that society. Marx agreed with Engels's idea that the working class would lead a revolution against the rich. He added this idea to his own philosophy.

Engels stayed in Paris to help Marx write The Holy Family. This book criticized the Young Hegelians. It was published in early 1845. Engels's first work with Marx was for the Deutsch–Französische Jahrbücher. During this time, Marx and Engels joined a secret revolutionary group called the League of the Just. This group wanted to create a society where everyone was equal.

Marx was forced to leave Paris by French authorities in February 1845. He moved to Brussels with his family. Engels left Paris in September 1844 and went back to his home in Barmen, Germany. He worked on his book, The Condition of the Working Class in England, which came out in May 1845. Even before his book was published, Engels moved to Brussels in April 1845. He wanted to work with Marx on another book, German Ideology. While in Barmen, Engels also started contacting socialists to raise money for Marx's publications. These contacts became important later for their political organizing.

Life in Brussels

Belgium was a new country founded in 1830. It had a very open constitution and was a safe place for people with new ideas from other countries. From 1845 to 1848, Engels and Marx lived in Brussels. They spent much of their time organizing German workers in the city. Soon after they arrived, they joined the secret German Communist League. This group was made up of revolutionaries from different European cities.

The Communist League asked Marx and Engels to write a short book explaining the ideas of communism. This book became Manifesto of the Communist Party, also known as The Communist Manifesto. It was first published on February 21, 1848. It ends with the famous words: "Let the ruling classes tremble at a Communistic revolution. The proletariat have nothing to lose but their chains. They have a world to win. Working Men of All Countries, Unite!"

Engels's mother wrote him a letter expressing her worries. She said he had "really gone too far" and begged him "to proceed no further."

Back to Prussia

In 1848, a revolution started in France. It quickly spread to other parts of Western Europe. These events made Engels and Marx return to their home country, Prussia, specifically to the city of Cologne. In Cologne, they started a new daily newspaper called the Neue Rheinische Zeitung. Both Marx and Engels were editors.

Engels's parents hoped he would "turn to activities other than those which you have been pursuing." They thought he should move to America and start a new life. They even said they would stop sending him money. But Engels and his parents worked things out. He did not have to leave England or lose their financial help. In 1851, Engels's father visited him in Manchester. During the visit, his father arranged for Engels to manage the Manchester office of the family business.

In 1849, Engels went to the Kingdom of Bavaria. He took part in the Baden and Palatinate revolutionary uprising. This was a very dangerous situation. Engels wrote a series of reports on the revolution and war for independence in Hungary. These articles appeared regularly in the Neue Rheinische Zeitung. However, the newspaper was shut down in June 1849. After that, Marx lost his Prussian citizenship and had to flee to Paris and then London. Engels stayed in Prussia and joined an armed uprising in South Germany. He was an assistant to a volunteer group. When the uprising failed, Engels was one of the last to escape by crossing into Switzerland. Marx and others worried about Engels until they heard he was safe.

Engels traveled through Switzerland as a refugee. He finally reached safety in England. On June 6, 1849, Prussian authorities issued an arrest warrant for Engels. It described him as "height: 5 feet 6 inches; hair: blond; eyes: blue; beard: reddish; speaks very rapidly and is short-sighted." Engels himself admitted his "short-sightedness" in a letter. Once safe in Switzerland, Engels wrote about his memories of the military campaign against the Prussians. This became the article "The Campaign for the German Imperial Constitution."

Back in Britain Again

Engels wanted to help Marx with his new newspaper in London. So, he found a way to travel to London. On October 5, 1849, Engels arrived in Genoa, Italy. From there, he sailed on an English ship called the Cornish Diamond. The trip across the Mediterranean and around Spain took about five weeks. Finally, the ship sailed up the River Thames to London on November 10, 1849, with Engels on board.

When he returned to Britain, Engels went back to work at his father's company in Manchester. He did this to help Marx financially while Marx worked on Das Kapital. This time, the police watched Engels closely. He had different "official" and "unofficial" homes in Manchester. He lived with Mary Burns using false names to avoid the police. We don't know many details because Engels destroyed over 1,500 letters between himself and Marx after Marx died. He did this to keep their secret lifestyle hidden.

Even with his work at the factory, Engels found time to write a book about Martin Luther and the 1525 peasant war in Germany. It was called The Peasant War in Germany. He also wrote many newspaper articles.

Marx and Engels spoke out against Louis Bonaparte. This was when he took control of the French government and made himself president for life in 1851. Engels wrote to Marx calling the event "comical." Marx later used this idea in his essay about the event, calling it The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte.

Engels started as an office clerk at his father's factory in Manchester. He worked his way up and became a partner in the company in 1864. Five years later, Engels retired from the business. This allowed him to focus more on his studies. At this time, Marx lived in London. They exchanged ideas through daily letters. One idea they thought about was a possible revolution in Russia. As early as 1853, Engels and Marx thought there might be a revolution in Russia. They believed it would start in St. Petersburg and lead to a civil war.

In 1870, Engels moved to London. He and Marx lived there until Marx's death in 1883. Engels's London home from 1870 to 1894 was at 122 Regent's Park Road. He later moved to 41 Regent's Park Road, Primrose Hill, where he died.

Mary Burns died suddenly in 1863. After her death, Engels became close with her younger sister, Lizzie. They lived together as a couple in London. They married on September 11, 1878, just hours before Lizzie's death.

His Later Years

Later in their lives, both Marx and Engels began to think that in some countries, workers might be able to achieve their goals peacefully. Engels believed that socialists were "evolutionists." This meant they thought change could happen gradually. But they still believed in a social revolution.

After Marx died, Engels spent much of his remaining years editing Marx's unfinished parts of Das Kapital. But he also wrote many other important works. Engels used ideas from anthropology to show that family structures have changed throughout history. He argued that the idea of monogamous marriage came from the need for men in class society to control women. This was to make sure their own children would inherit their property. He believed that a future communist society would allow people to choose their relationships freely, without money worries. One of his best works on this topic is The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State.

Engels died of throat cancer in London on August 5, 1895, at age 74. After being cremated, his ashes were scattered off Beachy Head, as he had asked. He left a lot of money to Eduard Bernstein and Louise Freyberger.

Friedrich Engels's Personality

Engels enjoyed poetry, fox hunting, and hosting Sunday parties. At these parties, many smart people from London's left-wing groups would gather. One person who often attended said that "no one left before two or three in the morning." His personal motto was "take it easy." He said "jollity" was his favorite good quality.

Robert Heilbroner described Engels as "tall and rather elegant." He looked like someone who enjoyed fencing and riding horses. He had even swum the Weser River four times without stopping. Heilbroner also said Engels was "gifted with a quick wit and facile mind." He had a cheerful personality and could "stutter in twenty languages." He greatly enjoyed wine and other "bourgeois pleasures." Engels preferred romantic relationships with working-class women. He found a long-term partner in Mary Burns, though they never married. After her death, he was romantically involved with her younger sister, Lydia Burns.

Engels was a polyglot. He could write and speak many languages. These included Russian, Italian, Portuguese, Irish, Spanish, Polish, French, English, German, and the Milanese dialect.

Friedrich Engels's Legacy

Vladimir Lenin, a famous leader, wrote about Engels. He said that after Karl Marx, Engels was the best scholar and teacher for workers worldwide. Lenin said that Marx and Engels were the first to explain that socialism was not just a dream. Instead, it was the natural outcome of how society's ways of making things developed. They believed that all history has been a history of different social classes struggling against each other.

Some people argue that Engels is unfairly blamed for the bad things done by Communist governments. These include countries like China and the Soviet Union. Historian Tristram Hunt says that Engels is "left holding the bag of 20th century ideological extremism." Meanwhile, Karl Marx is seen as more acceptable. Hunt believes that Engels or Marx cannot be blamed for crimes committed by people generations later.

Some writers, like Robert Service, are less forgiving. They point out that the anarchist Mikhail Bakunin predicted the oppressive side of their ideas. Bakunin argued that Marx and Engels wanted a strong central government. While they talked about "free associations of producers," they also supported strict rules and a clear chain of command. Paul Thomas says that Engels was very important in spreading Marx's writings. But he also changed Marx's ideas when he edited and published them. Engels tried to fill in gaps in Marx's system and apply it to other areas. He especially emphasized historical materialism. He made it sound like a scientific discovery and a fixed doctrine. This helped create "Marxism" as we know it.

Since 1931, a Russian city has been named after Engels—Engels, Saratov Oblast. It was the capital of the Volga German Republic in the Soviet Union. Another town named Marx is about 30 kilometers northeast. In 2014, Engels's "magnificent beard" inspired a climbing wall sculpture in Salford. This 16-foot-high beard statue was meant to be a "symbol of wisdom and learning." It was planned for the campus of the University of Salford.

In 2017, a Soviet-era statue of Engels was put up in Manchester. It was brought from a village in Ukraine. This happened after Ukraine passed laws banning communist symbols. The 3.5-meter statue now stands in Tony Wilson Place in Manchester. This shows the important influence Manchester had on Engels's work.

The Friedrich Engels Guards Regiment was a special guard unit in East Germany. It was named "Friedrich Engels" in 1970.

His Influences

Engels criticized some early socialists, but his own beliefs were influenced by the French socialist Charles Fourier. From Fourier, Engels got four main ideas about what a communist society would be like.

First, he believed everyone could fully develop their talents. This would happen by getting rid of specialized jobs. Without specialization, people could choose any job they wanted for as long or as short a time as they wished. For example, someone could be a baker one year and an engineer the next.

Second, because workers could switch jobs, the basic idea of dividing labor would disappear. If anyone can do any job, then there are no longer any barriers to different types of work.

Third, once the division of labor was gone, the division of social classes based on who owns property would also disappear. If a farmer owns a farm, that farmer controls its resources. The same applies to owning a factory or a bank. Without labor division, no single class could claim special rights to a way of making things. This is because everyone would be able to use it.

Finally, Engels concluded that getting rid of social classes would remove the only purpose of the state. He believed the state's only job was to manage conflicts between classes. With no social classes based on property, the state would become unnecessary. This is how Engels imagined a communist society would be achieved.

Major Works by Friedrich Engels

The Holy Family (1844)

Marx and Engels wrote this book in November 1844. It criticized the ideas of the Young Hegelians, who were popular thinkers at the time. The title was chosen by the publisher and was meant to be a sarcastic joke about the Bauer brothers and their followers.

The book caused some arguments. One of the Bauer brothers tried to argue against it in an article in 1845. He said Marx and Engels misunderstood him. Marx later replied to this in his own article.

The Condition of the Working Class in England (1845)

This book is a study of the very poor conditions of working people in Manchester and Salford. It was based on what Engels saw himself. The book also contains important thoughts on socialism. It was first published in German and only translated into English in 1887. It didn't have much impact in England at first. But it became very important for historians studying British industrialization in the 20th century.

The Peasant War in Germany (1850)

This book tells the story of a peasant uprising in Germany in the early 1500s. Engels compared it to the more recent revolutions that happened across Europe in 1848–1849.

Anti-Dühring (1878)

This book is also known as Herr Eugen Dühring's Revolution in Science. It is a detailed criticism of the ideas of Eugen Dühring, a German philosopher. In this book, Engels looks at new discoveries in science and math. He tries to show how the ideas of dialectics (a way of understanding change) apply to nature. Many of these ideas were later developed in his unfinished work, Dialectics of Nature. Three chapters of Anti-Dühring were later published separately as Socialism: Utopian and Scientific.

Socialism: Utopian and Scientific (1880)

This was one of the best-selling socialist books of its time. In it, Engels briefly described the ideas of famous utopian socialists like Charles Fourier and Robert Owen. He pointed out their strengths and weaknesses. He also explained the scientific socialist way of understanding capitalism. He outlined how society and economy developed from the viewpoint of historical materialism.

The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State (1884)

In this book, Engels argues that the family is always changing. He says it has been shaped by capitalism. The book looks at the history of the family in relation to social classes, the control of women, and private property.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Friedrich Engels para niños

In Spanish: Friedrich Engels para niños