German Peasants' War facts for kids

Quick facts for kids German Peasants' War |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the European wars of religion and the Protestant Reformation |

|||||||

Map showing the locations of the peasant uprisings and major battles |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 300,000 | 6,000–8,500 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| >100,000 | Minimal | ||||||

The German Peasants' War, also known as the Great Peasants' Revolt, was a large uprising that happened in German-speaking parts of Central Europe from 1524 to 1525. It was the biggest popular uprising in Europe before the French Revolution in 1789.

The revolt failed because powerful nobles strongly opposed it. They defeated the poorly armed peasants and farmers. Many thousands of peasants died, and the survivors faced punishments. They achieved very few of their goals. This war was similar to earlier revolts, mixing economic and religious reasons. Some religious leaders, like Thomas Müntzer, supported the peasants. The main fighting happened in the middle of 1525.

The war started with separate rebellions in what is now southwestern Germany and Alsace. It then spread to central and eastern Germany and present-day Austria. After the uprising in Germany was put down, it briefly appeared in some Swiss regions.

The peasants faced huge challenges. Their movement was very democratic, so they didn't have a strong command structure. They also lacked powerful weapons like cannons and cavalry (soldiers on horseback). Most peasants had little to no military experience. On the other side, their opponents had skilled military leaders, well-trained armies, and plenty of money.

The revolt used some ideas from the new Protestant Reformation. Peasants hoped for more influence and freedom. Some Radical Reformers, especially Thomas Müntzer, encouraged the revolt. However, Martin Luther, a main leader of the Reformation, condemned the uprising. He sided with the nobles. Luther wrote that the violence was evil and urged the nobles to stop the rebels. This condemnation by Luther helped lead to the peasants' defeat.

Contents

Why the Peasants Revolted

Historians have different ideas about why the revolt happened. Some think it was mainly about the new religious ideas from Luther. Others believe wealthy peasants wanted to protect their rights and wealth. Still others think it was a protest against the rise of stronger, more central governments.

Life in the 1500s

In the 1500s, many parts of Europe were linked by the Holy Roman Empire. This was a loose group of hundreds of smaller territories, each ruled by a prince or a city. The Holy Roman Emperor had little power over these local rulers. At the time of the Peasants' War, Charles V was the Emperor.

Local princes were taxed by the powerful Catholic Church. Many princes wanted to break away from the Church. This would allow them to control their own churches and keep the tax money. Many German princes supported this idea, using the slogan "German money for a German church."

Princes Gain Power

Princes often tried to make their free peasants into serfs. Serfs were like slaves, tied to the land and forced to work for the lord. Princes did this by raising taxes and bringing in new laws based on old Roman laws. These laws helped princes own all the land. This removed the older feudal idea where land was shared between a lord and a peasant, giving peasants some rights. By changing these laws, princes became richer and more powerful over their peasant subjects.

Luther and Müntzer's Different Views

Martin Luther was the most important leader of the Reformation in Germany. At first, he tried to stay neutral in the Peasants' War. He criticized both the unfair treatment of peasants and the peasants' decision to fight. Luther believed that work was a duty on Earth. He thought peasants should farm and rulers should keep the peace. He could not support the war because it broke the peace.

As the revolt grew in 1525, Luther fully supported the rulers. He wrote a strong pamphlet urging the nobility to stop the rebellion quickly and harshly. After the war, some people criticized Luther for his harsh words. He defended his views but also said the nobles had been too severe.

Thomas Müntzer was a different kind of religious leader. He strongly supported the peasants' demands for political and legal rights. Müntzer believed in a new world order that combined religious ideas with the peasants' social demands. In late 1524 and early 1525, Müntzer traveled where peasant armies were forming. He likely influenced their demands. He even helped some peasants write down their complaints.

Müntzer later led a rebel army in the Battle of Frankenhausen in May 1525. Luther and Müntzer often argued about their ideas. Luther's strong criticism of the peasants came out just as the rebels were being defeated.

Social Classes in the 1500s

In this time of big changes, powerful princes often worked with the middle class and clergy against the lesser nobles and peasants.

Princes

Many German rulers acted like kings in their own lands. They could collect taxes and borrow money as they wished. Running their governments and armies cost a lot, so they kept asking for more from their people. Princes also wanted to centralize power in towns and estates. They often gained wealth by taking over lands from lesser nobles.

Lesser Nobility

New military technology, like gunpowder and foot soldiers, made the traditional knights less important. Their expensive lifestyle meant they were losing money as prices went up. They tried to use old rights to get more money from their lands. This often meant treating peasants harshly, especially in southern Germany, which is why the war started there. Knights were also often in debt to townspeople.

Clergy

The clergy (church leaders) were the educated people of their time. They wrote most books. Some clergy were supported by nobles, while others appealed to common people. However, the Church was losing some of its power. Printing, trade, and new ideas from the Renaissance meant more people could read.

Some Catholic Church institutions had become corrupt. Many bishops and abbots were as harsh as princes in dealing with their subjects. They sold indulgences (pardons for sins) and taxed people directly. This corruption led Martin Luther to challenge the Church in 1517. Poorer clergy often joined the Reformation, wanting to extend Luther's ideas of equality to all of society.

Patricians

Many towns had special rights that meant they didn't pay taxes. So, most taxes fell on the peasants. Wealthy families called patricians controlled town councils and all important jobs. Like the princes, they tried to get as much money as possible from their peasants. They charged unfair tolls for roads and bridges. They also took over common lands, making it illegal for peasants to fish or cut wood there. Much of the money they collected was not properly recorded, leading to fraud.

Burghers

The growing middle class, called burghers, criticized the patricians. Burghers were well-off citizens, like guild masters or merchants. They wanted a say in town councils and an end to corruption. They also opposed the clergy's special privileges, like not paying taxes.

Plebeians

The plebeians were the new class of city workers, like journeymen and street vendors. Even some ruined burghers joined them. Although they could technically become burghers, wealthy families often stopped them from getting higher positions. So, their temporary jobs often became permanent, without civic rights. Plebeians usually didn't own property.

Peasants

Peasants were at the very bottom of society and were heavily taxed. In the early 1500s, they couldn't hunt, fish, or cut wood freely anymore. Lords had taken control of common lands. Lords could use peasant land as they wished, even destroying crops with their wild game hunts. Peasants needed the lord's permission and had to pay a tax to marry. When a peasant died, the lord took their best cattle, clothes, and tools. The justice system, run by clergy or wealthy townspeople, offered peasants no help.

Military Differences

Swabian League Army

The Swabian League was a group of princes and cities. Their army was led by Georg, Truchsess von Waldburg, who became known as "Bauernjörg" (Peasant George) or the "Scourge of the Peasants." The League's main base was in Ulm. Each member contributed soldiers and knights to the army.

Their foot soldiers were called landsknechte. These were professional mercenary soldiers, paid monthly. They were well-organized into regiments and companies. Each company had its own flag. The landsknechte had their own community assembly, which helped keep order. The League also relied on the nobility's armored cavalry, which was very effective.

Peasant Armies

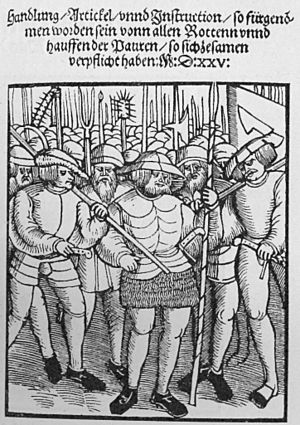

Peasant armies were organized into groups called haufen. These groups varied in size, from a few thousand to as many as 18,000. Each haufen was divided into smaller units. Like the landsknechte, they had commanders, lieutenants, and captains. Officers were usually elected by the peasants themselves.

The peasant army made decisions in a "ring," where peasants gathered in a circle to discuss plans. They also had leaders like a supreme commander and a marshal to keep order.

Peasants were good at building defenses. They used the wagon fort tactic, where wagons were chained together to create a strong defensive position. They dug ditches and used timber to block gaps. This tactic was mobile and could be set up quickly.

However, peasants lacked cavalry and armor. They had few horses and used their mounted men mainly for scouting. Not having cavalry to protect their sides or break through enemy lines was a big problem. Peasants often served in rotation, going back to their villages after a week or so. This meant others had to do their farm work, sometimes even producing supplies for their enemies.

Key Events of the War

Outbreak in the Southwest

The revolt began in 1524 during harvest time in Stühlingen, near the Black Forest. The Countess of Lupfen ordered serfs to collect snail shells after several bad harvests. Within days, 1,200 peasants gathered. They made a list of complaints, chose leaders, and raised a banner. Soon, most of southwestern Germany was in open revolt. The uprising spread across the Black Forest, along the Rhine river, to Lake Constance, and into Bavaria and Tyrol.

The Twelve Articles

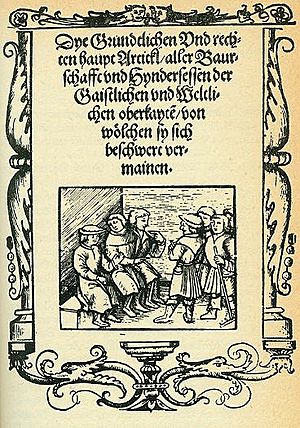

On February 16, 1525, 25 villages near Memmingen rebelled. They demanded better economic conditions and political rights. They complained about forced labor, land use, and church taxes. The city council expected small demands, but the peasants presented a clear list of grievances. These became the famous Twelve Articles.

On March 6, 1525, about 50 peasant leaders from different groups met in Memmingen. They agreed to work together against the Swabian League. On March 15 and 20, they adopted the Twelve Articles and a Federal Order. Their symbol was the Bundschuh, a laced boot. Over 25,000 copies of the Twelve Articles were printed in two months, spreading quickly across Germany.

The Twelve Articles demanded:

- The right for communities to choose and remove their own clergymen.

- Using the "great tithe" (a tax on wheat and wine) for public needs, after paying the pastor.

- Ending the "small tithe" (a tax on other crops).

- Ending serfdom (being tied to the land).

- Ending death tolls (taxes paid when a peasant died).

- Restoring fishing and hunting rights.

- Returning common lands taken by nobles.

- Limiting excessive forced labor, taxes, and rents.

- Ending unfair justice and administration.

Battle of Leipheim

48°26′56″N 10°13′15″E / 48.44889°N 10.22083°E

On April 4, 1525, 5,000 peasants gathered near Leipheim to fight the city of Ulm. They had cannons and took a strong position. The Swabian League's commander, the Truchsess, tried to negotiate while moving his troops. His cavalry attacked a smaller group of peasants, taking 250 prisoners.

Then, the Truchsess attacked the main peasant force. When the peasants saw the large size of his army (1,500 horse, 7,000 foot soldiers, and 18 cannons), they began to retreat. Many tried to escape across the Danube river, and 400 drowned. The Truchsess's cavalry killed another 500. This was the first major battle of the war.

Weinsberg Massacre

49°9′1.90″N 9°17′0.20″E / 49.1505278°N 9.2833889°E

Peasants from the Neckar valley, led by Jakob Rohrbach, joined other peasant groups. This larger group, called the "Bright Band," marched to Weinsberg. There, they attacked and captured the castle, because most of its soldiers were away. They took the Count of Helfenstein, the Austrian Governor of Württemberg, and about 70 other nobles prisoner. The peasants then forced these nobles to run through a gauntlet of pikes, a brutal form of execution. Rohrbach even ordered a piper to play music during this event.

Many other peasant leaders were shocked by Rohrbach's actions. He was removed from command and replaced by a knight, Götz von Berlichingen. This massacre angered Martin Luther greatly. He condemned the peasants for their actions and for daring to revolt.

Battle of Frankenhausen

- 51°21′21″N 11°6′4″E / 51.35583°N 11.10111°E

On April 29, 1525, peasant protests in Thuringia turned into a full revolt. Many townspeople joined. They stormed the castle of the Counts of Schwarzburg. By May 11, Thomas Müntzer arrived with 300 fighters, and thousands more peasants gathered, making their force about 6,000 strong.

The Landgrave Philip of Hesse and Duke George of Saxony led their professional Landsknecht troops towards Frankenhausen. These troops were experienced, well-equipped, and had high morale. The peasants, however, had poor equipment and little training. They argued about whether to fight or negotiate.

On May 15, Philip's troops joined the Saxon army. They broke a truce and launched a strong attack with infantry, cavalry, and artillery. The peasants were surprised and fled in panic towards the town. The princes' forces followed and attacked them continuously. Most of the rebels were killed in what became a massacre. Estimates say 3,000 to 10,000 peasants died, while the Landsknecht army lost very few soldiers. Müntzer was captured, tortured, and executed on May 27.

Battle of Böblingen

The Battle of Böblingen (May 12, 1525) caused the most deaths in the war. Peasants marched towards the Truchsess's camp. They set up three camps and formed four units. Their 18 cannons were on a hill. The League's cavalry surrounded the peasants and chased them for miles. The peasant force lost about 3,000 men, while the League lost fewer than 40 soldiers.

Battle of Königshofen

At Königshofen on June 2, peasant commanders Wendel Hipfler and Georg Metzler set up camp. When they saw enemy cavalry approaching, they moved their wagon-fort and cannons to a hill. They formed ranks behind their cannons, with the wagon-fort protecting their rear. The peasants fired their cannons, but the Truchsess ordered an attack from the front and the rear at the same time. Panic spread among the peasants. Only 600 peasants remained by nightfall. The Truchsess's soldiers found about 500 peasants who had pretended to be dead.

Siege of Freiburg im Breisgau

Freiburg, a Habsburg territory, struggled to gather enough soldiers to fight the peasants. When the city sent out troops, the peasants simply disappeared into the forest. After the Duke of Baden refused the Twelve Articles, peasants attacked monasteries. In early May, Hans Müller arrived near Freiburg with over 8,000 men. Other groups joined, bringing the total to 18,000. The city was surrounded, and the peasants planned a siege. On May 23, the city leaders surrendered and joined the "Christian Union" with the peasants.

End of the War

After the peasants took Freiburg, Hans Müller took some of his group to help with a siege at Radolfzell. The rest of the peasants went back to their farms. On June 4, near Würzburg, Müller's small group joined other Franconian farmers. They met the army of Götz von Berlichingen, an experienced knight. He easily defeated the peasants. In about two hours, more than 8,000 peasants were killed.

Several smaller uprisings were also put down. By September 1525, all fighting and punishments had ended. Emperor Charles V and Pope Clement VII thanked the Swabian League for stopping the revolt.

Why the Rebellion Failed

The peasant movement failed for several reasons. There was a lack of communication between the different peasant groups due to their separation. Also, they were militarily weaker than their opponents. While some professional soldiers and knights joined the peasants, the Swabian League had better military technology, strategy, and experience.

After the German Peasants' War, the rights and freedoms of peasants were reduced even further. They were pushed out of political life. In some areas, like Kempten and Tyrol, peasants did manage to create local assemblies and committees to deal with issues like taxes. However, the main goals of the Twelve Articles were not achieved.

Another result of the war was that thousands of peasants died. This devastated the economies of the affected regions for one or two generations because there weren't enough workers.

Images for kids

-

Coat of arms of the Swabian League, with a flag of St. George.

See also

In Spanish: Guerra de los campesinos alemanes para niños

In Spanish: Guerra de los campesinos alemanes para niños

- List of peasant revolts

- Popular revolt in late-medieval Europe

- Melchior Rink, who was accused by Lutherans of being an instigator of the war

- Wir sind des Geyers schwarzer Haufen, a World War I-era song about the German Peasants' War.

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |