Thomas Müntzer facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Thomas Müntzer

|

|

|---|---|

Müntzer, imagined in a 1608 engraving by Christoffel Van Sichem

|

|

| Born | c. 1489 Stolberg, County of Stolberg, Holy Roman Empire

|

| Died | 27 May 1525 (aged 35–36) Free Imperial City of Mühlhausen, Holy Roman Empire

|

| Occupation | Radical Reformation preacher, theologian, early Reformer |

| Signature | |

Thomas Müntzer (around 1489 – 27 May 1525) was a German preacher and thinker during the early Reformation. He disagreed with both Martin Luther and the Catholic Church. Müntzer openly challenged the powerful rulers of his time in central Germany.

He believed Luther was too willing to work with these rulers. Müntzer became a key leader in the German Peasants' War of 1525. This was a big uprising of farmers and common people.

In 1514, Müntzer became a priest in Braunschweig. There, he started to question the Catholic Church's teachings. He then became a follower of Martin Luther, who helped him get a job in Zwickau. Müntzer's ideas became more focused on spiritual visions and the end of the world. By 1523, when he arrived in Allstedt, he had completely broken away from Luther. During the peasant uprisings in 1525, Müntzer organized an armed group in Mühlhausen. He was captured after the Battle of Frankenhausen and later executed.

Thomas Müntzer was a very controversial figure in the German Reformation. Even today, people still debate his actions. He is now seen as an important person in the early Reformation. He also played a big role in the history of European revolutionaries. Many experts believe his revolutionary actions came from his religious beliefs. Müntzer thought the end of the world was near. He felt it was his job to help God bring about a new era.

Contents

Who Was Thomas Müntzer?

Thomas Müntzer was born in late 1489 or early 1490. His hometown was Stolberg in the Harz Mountains of central Germany. It's a myth that his father was executed by rulers. Müntzer likely came from a comfortable family. This is shown by his long education. Both his parents were alive in 1520. His mother died around that time.

Soon after 1490, his family moved to Quedlinburg. In 1506, he enrolled at the University of Leipzig. He might have studied arts or theology there. We don't have all the records from that time. It's not certain if he graduated from Leipzig. In late 1512, he enrolled at the Viadriana University in Frankfurt an der Oder. By 1514, he had a job in the church. He probably had a bachelor's degree in theology or arts. He might have even had a master's degree.

During this time, he also worked as a teacher. He taught in schools in Halle and Aschersleben. He claimed he formed a "league" against the Archbishop of Magdeburg. We don't know what this group was meant to do.

Early Work and Luther's Influence

In May 1514, Müntzer became a priest in Braunschweig. He worked there on and off for several years. Here, he started to question the Catholic Church. For example, he criticized the selling of indulgences. These were like passes to reduce punishment for sins. Friends called him a "castigator of unrighteousness." This means he spoke out against unfairness. Between 1515 and 1516, he also taught at a nunnery in Frose.

In autumn 1517, he was in Wittenberg. He met Martin Luther there. He joined in the big talks before Luther posted his 95 Theses. He went to university lectures. He learned about Luther's ideas. He also heard ideas from humanists. One of them was Andreas Bodenstein von Karlstadt. Karlstadt later became a strong opponent of Luther. Müntzer did not stay long in Wittenberg. He was seen in other places in Thuringia and Franconia.

He was paid for his job in Braunschweig until early 1519. Then he went to Jüterbog. He was asked to fill in for a preacher named Franz Günther. Günther had been preaching new ideas. But he was attacked by local Franciscans. So he left, and Müntzer took over. Müntzer continued where Günther left off. Soon, local church leaders complained. They said Müntzer's ideas were against church teachings. By this time, Müntzer was not just following Luther. He was studying the works of mystics like Henry Suso and Johannes Tauler. He wondered about getting wisdom through dreams and visions. He also studied the early history of the Christian church. He was in touch with other reformers like Karlstadt.

In June 1519, Müntzer went to the Leipzig Debate. This was a big debate between Luther and the Catholic Church. Müntzer was noticed by Luther. Luther recommended him for a temporary job in Zwickau. However, at the end of that year, he was still working at a nunnery in Beuditz. He spent the winter studying mystics, humanists, and church historians.

Time in Zwickau

In May 1520, Müntzer used Luther's recommendation. He became a temporary preacher at St Mary's Church in Zwickau. Zwickau was a busy town with about 7,000 people. It was near the border with Bohemia. Zwickau was important for iron and silver mining. Many common people, especially weavers, lived there. Money from mining created a big gap between rich and poor. This caused a lot of social tension.

At St Mary's, Müntzer continued his reform ideas. This led to conflicts with the church. He still saw himself as Luther's follower. So, the town council supported him. When the main preacher returned, the council gave Müntzer a permanent job at St Katharine's Church.

St Katharine's was the church for weavers. Even before Luther's ideas, there was a reform movement in Zwickau. It was inspired by the Bohemian Reformation of the 15th century. This was especially true for the radical Taborite group. Among the weavers, this movement was strong. Nikolaus Storch was active here. He was a self-taught radical. He believed in spiritual messages through dreams. Soon, he and Müntzer worked together.

In the next few months, Müntzer disagreed more and more with the local Lutherans. He got involved in riots against Catholic priests. The town council became worried about what was happening at St Katharine's. In April 1521, they decided it was enough. Müntzer was fired and had to leave Zwickau.

Prague and His Travels

Müntzer first went to Žatec (Saaz) in Bohemia. This town was known as a safe place for the radical Taborites. But Müntzer only stopped there on his way to Prague. In Prague, the Hussite Church was already strong. Müntzer hoped to find a safe home there. He wanted to develop his ideas, which were now very different from Luther's. He arrived in late June 1521. He was welcomed as a "Martinist" (a follower of Luther). He was allowed to preach and give lectures.

He also wrote down his beliefs. This document is known as the Prague Manifesto. It exists in four forms: one in Czech, one in Latin, and two in German. One German version was like a large poster. The document shows how much he had moved away from Luther. It also shows how much he believed the reform movement was about the end of the world. He wrote, "I, Thomas Müntzer, ask the church not to worship a silent God, but a living and speaking one."

In late 1521, the Prague authorities realized Müntzer was not who they thought. They forced him to leave town. For the next year, he wandered around Saxony. He visited Erfurt and Nordhausen. He spent weeks in each place, looking for jobs but not getting hired. He also visited his hometown of Stolberg to give sermons. In November 1522, he went to Weimar for a debate. From December 1522 to March 1523, he worked as a chaplain at a nunnery in Glaucha, near Halle. He had little chance to make changes there. He tried to give communion in a new way to a noblewoman. This likely led to his dismissal.

Allstedt: A New Start

His next job was more stable and successful. In early April 1523, he became a preacher at St John's Church in Allstedt in Saxony. He got this job with help from Felicitas von Selmenitz. He worked with another reformer, Simon Haferitz. Allstedt was a small town, like a large village, with about 600 people. It had a big castle on a hill.

As soon as he arrived, Müntzer started preaching his reformed ideas. He held church services and masses in German. His preaching was very popular. People from nearby towns and the countryside came to Allstedt. Some reports say over two thousand people came every Sunday. Within weeks, Luther heard about this. He wrote to the Allstedt authorities. He asked them to send Müntzer to Wittenberg for a closer look. Müntzer refused to go. He was too busy with his Reformation. He didn't want secret discussions. Around this time, he also married Ottilie von Gersen, a former nun. In spring 1524, they had a son.

Luther was not the only one worried. The Catholic Count Ernst von Mansfeld tried to stop his people from going to Allstedt. Müntzer felt confident enough to write to the count in September. He told him to stop his unfair rule. Müntzer wrote, "I am as much a Servant of God as you, so tread gently." He warned the count he would be much harsher than Luther was with the Pope.

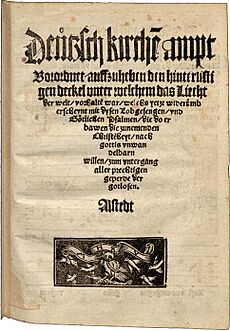

Throughout 1523 and into 1524, Müntzer strengthened his reformed services. He spread his message in Allstedt. He arranged for his German Church Service to be printed. He also printed the Protestation or Proposition by Thomas Müntzer, about his teachings. Another work was On the Counterfeit Faith. In this, he said true faith came from inner suffering.

In spring 1524, Müntzer's supporters burned a small chapel. This angered the abbess of a nearby nunnery. The town council and castle guard did nothing. But in July, Müntzer was invited to Electoral Duke Johann in Allstedt Castle. There, he preached his famous sermon. It was called The Sermon Before the Princes. In it, he warned the princes. He said they should join his reforms or face God's anger.

What a pretty spectacle we have before us now – all the eels and snakes coupling together immorally in one great heap. The priests and all the evil clerics are the snakes...and the secular lords and rulers are the eels... My revered rulers of Saxony...seek without delay the righteousness of God and take up the cause of the gospel boldly.

We don't know the princes' immediate reaction. But Luther quickly published his Letter to the Princes of Saxony about the Rebellious Spirit. He demanded that Müntzer be banished from Saxony. However, the princes just called everyone from Allstedt, including Müntzer, to a meeting in Weimar. After being questioned, they were warned about their future actions. This meeting made the town officials change their minds. They quickly stopped supporting Müntzer. On the night of 7 August 1524, Müntzer secretly left Allstedt. He had to leave his wife and son behind. They joined him later. He headed for the free city of Mühlhausen, about 65 km southwest.

Mühlhausen and Nuremberg

Mühlhausen was a city with 8,500 people. In 1523, social tensions grew strong. Poorer people gained some power from the town council. The radical reform movement kept up the pressure. A preacher named Heinrich Pfeiffer led this. He spoke out against the old church. So, when Müntzer arrived, there was already much tension. He wasn't given a pulpit, but he still preached. He also published pamphlets against Luther. His friend here was Pfeiffer. They didn't always share the same beliefs. But they both wanted reform and believed in spiritual inspiration. This allowed them to work closely.

A small change in city power happened in late September 1524. Leading town council members fled the city. But this change didn't last long. It failed partly because of disagreements among reformers. Also, farmers in the countryside didn't like the "unchristian behavior" of the city radicals. After only seven weeks, on 27 September, Müntzer had to leave his wife and child again. He escaped with Pfeiffer to a safer place.

He first traveled to Nuremberg in the south. There, he arranged to publish his anti-Luther pamphlets. One was called A Highly Provoked Vindication and Refutation of the unspiritual soft-living flesh in Wittenberg. Another was A Manifest Exposé of False Faith. City officials seized both. The first one was taken before any copies could be shared. Müntzer stayed quiet in Nuremberg. He thought it best to spread his ideas in print. He didn't want to end up in jail. He stayed there until November. Then he left for southwest Germany and Switzerland. Farmers and common people there were starting to organize. They were preparing for the big peasant uprising of 1525.

We don't have direct proof of what Müntzer did there. But he likely met leaders of the rebel groups. It's thought he met the Anabaptist leader Balthasar Hubmaier in Waldshut. We know he was in Basel in December. He met the reformer Oecolampadius there. He might also have met the Swiss Anabaptist Conrad Grebel. He spent weeks in the Klettgau area. There's some evidence he helped the peasants write their complaints. The famous "Twelve Articles" of the Swabian peasants were not written by Müntzer. But one important document, the Constitutional Draft, might have been his work.

The Final Months

In February 1525, Müntzer returned to Mühlhausen. He had been briefly arrested in Fulda but was released. He took over the pulpit at St Mary's Church. The town council didn't give permission, but a popular vote put him there. Immediately, he and Pfeiffer were very active. Pfeiffer had returned to the town three months earlier. In early March, citizens were asked to elect an "Eternal Council." This council would replace the old town council. Its duties went far beyond city matters. Surprisingly, neither Pfeiffer nor Müntzer were part of this new council.

Perhaps because of this, Müntzer then started the "Eternal League of God." This was an armed group. It was meant for defense. It was also a group of religious people ready for the coming end of the world. They met under a huge white banner. It had a rainbow painted on it. The words The Word of God will endure forever were also on it. In the countryside and nearby towns, people heard about Mühlhausen. Farmers and poor city people knew about the big uprising in southwest Germany. Many were ready to join.

In late April, all of Thuringia was in revolt. Peasant and commoner troops from different areas gathered. However, the princes were planning to stop the rebellion. The rulers had much better weapons. Their armies were more disciplined than the rebels. In early May, the Mühlhausen troops marched around northern Thuringia. But they failed to meet up with other rebel groups. They were content to loot and steal locally.

Luther strongly supported the princes. He traveled through southern Saxony. He visited Stolberg, Nordhausen, and the Mansfeld area. He tried to stop the rebels. But in some places, people booed him loudly. He then wrote a pamphlet called Against the Robbing and Murdering Hordes of Peasants. In it, he called for the rebellion to be crushed without mercy. The title and timing of this pamphlet were very bad. Thousands of German peasants died at the hands of the princely armies. Estimates say 70,000 to 100,000 peasants were killed.

Finally, on 11 May, Müntzer and his remaining troops arrived near Frankenhausen. They met rebels there who had asked for help. They set up camp on a hill. Soon after, the princes’ army arrived. This army had already crushed the rebellion in southern Thuringia. On 15 May, the battle began. It lasted only a few minutes. The streams on the hill ran with blood. Six thousand rebels were killed. Only a few soldiers died. Many more rebels were executed in the days that followed. Müntzer fled. But he was captured hiding in a house in Frankenhausen. A bag of papers and letters he carried revealed who he was. On 27 May, he was executed with Pfeiffer. This happened outside the walls of Mühlhausen.

Thomas Müntzer's Writings

Here are some of the works Müntzer had printed during his lifetime:

- German Church Service (May 1523): This was a new way to hold church services in German.

- The Order and Explanation of the German Church Service in Allstedt (May 1523)

- A Sober Missive to his Dear Brothers in Stolberg, Urging them to Avoid Unrighteous Uproar (July 1523): A letter telling his brothers to avoid unfair riots.

- Counterfeit Faith (December 1523): About his belief that true faith came from inner suffering.

- Protestation or Proposition (January 1524): About his teachings.

- Interpretation of the Second Chapter of Daniel the Prophet (July 1524): His famous sermon to the princes.

- The German Evangelical Mass (August 1524)

- A Manifest Exposé of the False Faith, presented to the Faithless World (October 1524)

- A Highly-Provoked Vindication and a Refutation of the Unspiritual, Soft-Living Flesh in Wittenberg (December 1524): A strong defense against Luther.

Müntzer's Impact and Legacy

In his last two years, Müntzer met other radical thinkers. Some important ones were Hans Hut, Hans Denck, Melchior Rinck, Hans Römer, and Balthasar Hubmaier. All of them became leaders of the new Anabaptist movement. This movement had similar ideas to Müntzer's. While they weren't all "Müntzerites," they shared some common teachings. A connection links Müntzer, the early Anabaptists, the "Kingdom of Münster" in 1535, and later radical groups.

Müntzer also had a short-lived impact on the official church. In towns where he had been active, his reformed church services were still used ten years after his death.

Friedrich Engels and Karl Kautsky saw Müntzer as an early revolutionary. They based their ideas on the work of Wilhelm Zimmermann. Zimmermann wrote an important history of the Peasants' War in 1843. Müntzer is important not just as an early "social revolutionary." His actions also influenced Luther and his reforms.

Interest in Müntzer grew at different times in German history. This happened during the creation of German national identity (1870-1914). It also happened after the 1918 revolution in Germany. East Germany, after 1945, looked for its "own" history. Müntzer's image was even on the 5 East German Mark banknote. Interest also rose before the 450th anniversary of the Peasant War in 1975. And again for the 500th anniversary of Müntzer's birth in 1989. The number of books and articles about Müntzer increased a lot after 1945. Before 1945, about 520 works appeared. Between 1945 and 1975, another 500 were published. From 1975 to 2012, 1800 more works came out.

Since about 1918, many fictional works about Müntzer have appeared. This includes over 200 novels, poems, plays, and films. Almost all are in German. A film about his life was made in East Germany in 1956. It was directed by Martin Heilberg and starred Wolfgang Stumpf. In 1989, just before the Berlin Wall fell, the Peasants' War Panorama opened. It has the largest oil painting in the world. Müntzer is in the center of this painting. The painter was Werner Tübke.

Müntzer's Wife

We know very little about Müntzer's wife, Ottilie von Gersen. She was a nun who left a nunnery because of the Reformation. Her family name might have been "von Görschen." She may have been one of sixteen nuns who left a convent near Allstedt. Eleven of them found safety in Allstedt. She and Müntzer married in June 1523. They had a son on Easter Day, 1524. It's possible she was pregnant again when her husband died. Their son may also have died by then. She wrote a letter to Duke Georg on 19 August 1525. She asked to get her belongings back from Mühlhausen. But her request was ignored. No other information about her life has been found.

See also

In Spanish: Thomas Müntzer para niños

In Spanish: Thomas Müntzer para niños

- Christian anarchism

- Christian socialism

- Utopian socialism

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |