John Ruskin facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

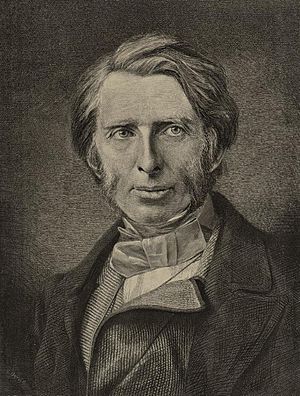

John Ruskin

|

|

|---|---|

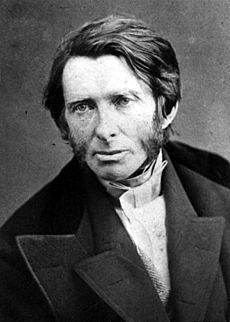

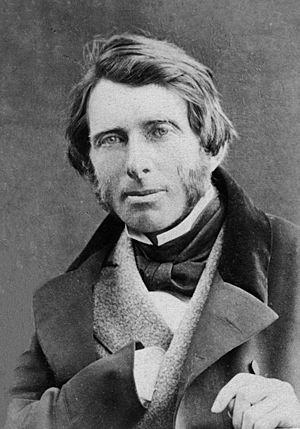

Ruskin in 1863

|

|

| Born | 8 February 1819 London, England

|

| Died | 20 January 1900 (aged 80) Coniston, Lancashire, England

|

| Alma mater | |

|

Notable work

|

|

| Spouse(s) | |

| Era | 19th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | |

|

Main interests

|

|

|

Notable ideas

|

|

|

Influenced

|

|

| Signature | |

John Ruskin (born February 8, 1819 – died January 20, 1900) was an English writer, thinker, and art critic during the Victorian era. He wrote about many different topics. These included geology, architecture, myths, birds, books, education, plants, and how countries manage their money and resources (political economy).

Ruskin was very interested in the work of Viollet le Duc, especially his dictionary on architecture. Ruskin thought it was "the only book of any value on architecture."

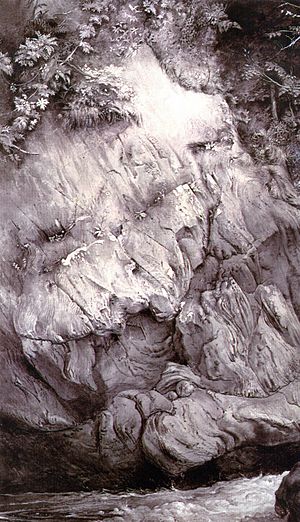

Ruskin used many different writing styles. He wrote essays, poems, lectures, travel guides, and even a fairy tale. He also drew detailed sketches and paintings of nature and buildings. His early writing on art was very fancy, but he later used simpler language. In all his work, he showed how nature, art, and society are connected.

Ruskin was very important in the late 1800s and early 1900s. After a quiet period, his fame grew again from the 1960s. Today, his ideas are seen as ahead of their time. He cared about the environment, how things can last a long time (sustainability), and traditional crafts.

Ruskin first became well-known with his book Modern Painters (1843). In it, he defended the artist J. M. W. Turner. He argued that artists should always show "truth to nature." In the 1850s, he supported the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, who were inspired by his ideas. Later, his work focused more on social and political issues. His book Unto This Last (1860, 1862) showed this change. In 1869, Ruskin became the first Professor of Fine Art at the University of Oxford. There, he started the Ruskin School of Drawing. In 1871, he began writing monthly "letters to the workmen and labourers of Great Britain." These were published as Fors Clavigera (1871–1884). In this long work, he shared his ideas for an ideal society. He also started the Guild of St George, an organization that still exists today.

Contents

Early Life and Learning

Family and Childhood

Ruskin was the only child of John James Ruskin and Margaret Cock. His father was a successful wine importer. His mother taught him to read the Bible from beginning to end. This had a big impact on his writing. His parents were very ambitious for him.

Ruskin was born in London in 1819. He grew up in Herne Hill, South London. He was mostly taught at home by his parents and tutors. He later studied at King's College London and then at the University of Oxford.

Travels and Art

Ruskin traveled a lot with his family when he was young. These trips helped him develop his love for art and nature. He visited the Lake District in England and relatives in Perth, Scotland. From 1825, his family traveled to France and Belgium. Later, they visited places like Strasbourg, Milan, and Venice. He especially loved the Alps. Venice became a very important city in his later work.

These travels allowed Ruskin to draw and write about nature. He wrote poems and articles about geology. He was very impressed by the illustrations of J. M. W. Turner. Ruskin learned to draw from artists like Charles Runciman and Copley Fielding.

His first published poem was "On Skiddaw and Derwent Water" in 1829. He also wrote articles about natural history. From 1837 to 1838, his work The Poetry of Architecture was published. It talked about how buildings should fit into their natural surroundings.

Time at Oxford

Ruskin started at the University of Oxford in 1837. He made important friends there, including the geologist William Buckland. In 1839, he won a poetry prize called the Newdigate Prize. He even met the famous poet William Wordsworth at the ceremony.

Ruskin's health was not always good. He also faced personal sadness when his first love, Adèle Domecq, got engaged to someone else. During a break from Oxford, he wrote his only fairy tale, The King of the Golden River. It was published in 1850. This story teaches about kindness and helping others. In 1842, Ruskin finished his studies at Oxford.

A Champion of Art

Modern Painters I

After his studies, Ruskin traveled in Italy, studying art. He decided to write a book defending the artist J. M. W. Turner. Turner's paintings were being criticized.

In 1843, Ruskin published Modern Painters (Volume I). He wrote it anonymously as "A Graduate of Oxford." He argued that modern landscape painters, especially Turner, were better than older artists. He believed that artists should paint "truth to nature." This meant showing the real world, not just following old rules. Ruskin described paintings with amazing detail and beauty.

This book changed how art criticism was done. It combined art, science, and ethics. It also started a strong friendship between Ruskin and Turner. After Turner died in 1851, Ruskin helped organize his vast collection of nearly 20,000 drawings.

Travels and Modern Painters II

In 1845, Ruskin traveled alone for the first time. He studied medieval art and architecture in France, Switzerland, and Italy. He was very impressed by the art in Venice. But he was also worried about how the city was changing and falling apart. This made him believe that old buildings should be preserved, not rebuilt.

In 1846, he published the second volume of Modern Painters. This book focused on older artists and was more about art theory. Ruskin argued that truth, beauty, and religion are all connected. He believed that great artists see beauty and share it through their art.

Marriage and Architecture

In 1848, Ruskin married Effie Gray, a family friend for whom he had written The King of the Golden River. Their early travels were limited due to events in Europe.

Ruskin became very interested in Gothic architecture. In 1849, he published The Seven Lamps of Architecture. This book had 14 drawings by Ruskin himself. It talked about seven important ideas for architecture: sacrifice, truth, power, beauty, life, memory, and obedience. He promoted a simple, Protestant form of Gothic style.

The Stones of Venice

In 1849, John and Effie Ruskin visited Venice. Ruskin spent his time drawing and studying the city's buildings. He was worried that famous buildings like the Ca' d'Oro would be destroyed.

From 1851 to 1853, Ruskin published his three-volume work, The Stones of Venice. It was a history of Venetian architecture. But it was also a warning about what was happening in England at the time. Ruskin believed that Venice had declined because its true Christian faith had weakened.

A famous part of The Stones of Venice is the chapter "The Nature of Gothic." Ruskin praised Gothic art because it showed the joy and freedom of the workers who created it. He believed workers should be allowed to think and express themselves, using their hands instead of machines. This idea was a criticism of how factories and industrial capitalism were changing society. This chapter greatly influenced the Arts and Crafts movement.

Supporting the Pre-Raphaelites

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was a group of artists who started in 1848. They wanted to paint nature with great detail, which was influenced by Ruskin's ideas.

Ruskin became friends with one of the artists, John Everett Millais. At first, Ruskin didn't like Millais's painting Christ in the House of His Parents. But he later defended the Pre-Raphaelites in letters to The Times newspaper. He supported Millais and other artists like William Holman Hunt and Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

Ruskin's marriage to Effie Gray ended in 1854. The annulment caused a public stir. Effie later married Millais.

Ruskin continued to help other artists. He gave money to Elizabeth Siddal, Rossetti's wife, to support her art. He also helped artists like John Brett and Edward Burne-Jones.

Ruskin also wrote reviews of art exhibitions. These reviews were very powerful and could make or break an artist's career. He also gave many of his own drawings to museums. His own artwork showed his careful observations of nature.

Ruskin's ideas also inspired architects to use the Gothic style. The Oxford University Museum of Natural History is an example of this "Ruskinian Gothic" style.

Ruskin and Education

Ruskin started teaching drawing classes at the Working Men's College in the 1850s. He believed that education could help workers feel more fulfilled. He wrote Elements of Drawing (1857) to help people learn to draw.

He was also involved with a girls' school called Winnington Hall. He visited often and gave them pictures and rocks. This led to his book The Ethics of the Dust (1866), which was a conversation with the girls about crystals and social ideas. Later, he supported Whitelands College, a training college for teachers. He also gave books and gems to Somerville College, one of Oxford's first colleges for women.

Modern Painters III and IV

In 1856, Ruskin published volumes III and IV of Modern Painters. In Volume III, he said that great art shows the "spirits of great men." He believed that only good people could truly appreciate beauty and turn it into great art. Volume IV talked about the geology of the Alps and how mountains affect people.

Public Speaker

Ruskin became a very popular public speaker in the 1850s. He gave lectures on art and architecture. His lectures were collected in books like The Political Economy of Art (later called A Joy For Ever). In these talks, he argued that true wealth is about goodness, and art shows how well a nation is doing. He believed people should spend their money wisely.

His ideas were sometimes criticized, especially by economists. But others, like Thomas Carlyle, praised his work. Ruskin also gave the first speech at the Cambridge School of Art in 1858.

Turner's Art Collection

When J. M. W. Turner died in 1851, he left nearly 20,000 artworks to the British nation. Ruskin was asked to help organize this huge collection. He spent a lot of time cataloging, framing, and preserving Turner's art. He even designed special cabinets to display 400 of Turner's watercolors.

A Change in Beliefs

In 1858, Ruskin traveled in Europe again. He saw a painting by Paolo Veronese in Turin. This experience, combined with a dull sermon, led him to question his strong Christian faith. He had already been doubting some Bible stories due to new scientific discoveries. This period was a big personal challenge for him. He later returned to Christianity.

Ideas for a Better Society

Social Critic: Unto This Last

In the late 1850s, Ruskin started focusing more on social issues. He was inspired by Thomas Carlyle. Ruskin began to strongly criticize industrial capitalism and the idea that people should only care about making money (utilitarianism). He started writing in a simpler style to make his message clear.

Ruskin believed that society should be like a family. He argued that the way work was divided in factories was unfair. He said that the study of economics ignored human feelings and how communities work together. For Ruskin, all societies should be based on social justice. His ideas influenced the concept of the "social economy" and charitable groups.

His four essays, Unto This Last, were published in a magazine in 1860. The magazine had to stop publishing them because many readers were upset. But others, like Carlyle, loved them.

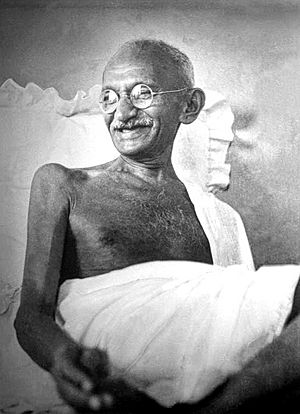

Ruskin's ideas in Unto This Last became very important later on. Mohandas Gandhi praised them and rewrote them in Gujarati. Many people who started the British Labour Party said Ruskin influenced them more than Karl Marx.

Ruskin believed in a structured society. He wanted to improve the lives of the poor. He thought society should move away from capitalism and towards a system where people cooperated. He believed in farming and traditional ways of life.

His next works, Munera Pulveris (1872) and Time and Tide (1867), also explored political ideas. He promoted honesty in work and fair treatment for employees.

After his father died in 1864, Ruskin inherited a lot of money. He used it for good causes. He supported Octavia Hill's work to provide better housing for the poor. He also started a shop selling pure tea and even paid people to keep the area around the British Museum clean. These small projects were his way of challenging society.

Lectures in the 1860s

Ruskin gave many lectures in the 1860s. He spoke about art, work, and war. His lecture Traffic (1864) talked about the connection between good taste and good morals. These lectures were published in The Crown of Wild Olive (1866).

Another important book was Sesame and Lilies (1865). It was based on lectures about education and good behavior. "Of Kings' Treasuries" talked about reading and the value of books. "Of Queens' Gardens" focused on the role of women. Ruskin believed women had an important role in the home and in society, balancing men's actions with compassion. This book was very popular and often given as a school prize.

Later Life and Legacy

Oxford Professor

In 1869, Ruskin became the first Slade Professor of Fine Art at Oxford University. He gave his first lecture in 1870. He said that a country's art shows its social and political strengths. He also spoke about England needing to set up colonies with its best people.

In 1871, Ruskin started his own art school at Oxford, The Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art. He gave money to the school and created a large collection of drawings and other materials to help students learn.

Ruskin's lectures were very popular. He talked about many subjects, including art, science, geology, and literature. He believed that "The teaching of Art... is the teaching of all things."

One of his most unusual projects was the "digging scheme" in 1874. He had Oxford students, including Oscar Wilde, work on mending a road. He wanted to teach them the value of honest manual labor. This experience influenced many of the students.

Ruskin resigned from Oxford in 1879 but returned in 1883. He resigned again in 1884 due to health issues and disagreements with the university.

Fors Clavigera and the Whistler Case

In 1871, Ruskin began writing his monthly "letters to the workmen and labourers of Great Britain" called Fors Clavigera (1871–84). These letters were very personal and covered many topics.

In 1877, Ruskin strongly criticized a painting by James McNeill Whistler. He said Whistler was "flinging a pot of paint in the public's face." Whistler sued Ruskin for libel. Ruskin was ill during the trial, but his friends defended him. Whistler won the case, but was only awarded a tiny amount of money. This event damaged Ruskin's reputation.

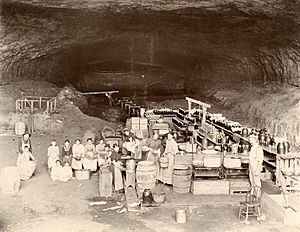

The Guild of St George

Ruskin founded his ideal society, the Guild of St George, in 1871. He wanted to show that people could still enjoy life in the countryside. The Guild aimed to farm land using traditional methods, in harmony with nature. It also wanted to enrich the lives of workers by inspiring them with beautiful objects. Ruskin gave a lot of his own money to the Guild.

The Guild bought land in different parts of England and Wales. It also encouraged traditional crafts like spinning and weaving.

The Guild's most lasting achievement was creating a collection of art, minerals, books, and other beautiful objects. This collection was housed in a museum in Sheffield, which opened in 1875. Ruskin wanted working people to see these beautiful things, just as he had seen them on his travels. The collection is now at the Millennium Gallery in Sheffield.

Later Travels and Writings

Ruskin continued to travel and study art in Europe. He wrote new travel guides, like Mornings in Florence (1875–77) and The Bible of Amiens (1880–85). He wanted to guide travelers to truly see the landscapes, buildings, and art.

His last major work was his autobiography, Praeterita (1885–89), which means 'Of Past Things'. It was a personal and selective account of his life.

In his later years, Ruskin's health declined. He suffered from periods of mental illness. He became less connected to the modern art world, which was moving towards "art for art's sake." He also criticized Darwinism.

Brantwood and Final Years

In 1871, Ruskin bought Brantwood house, by Coniston Water in the Lake District. This became his main home. He made many changes to the house and gardens. He built a larger harbor and added a turret to his bedroom for views of the lake.

Ruskin died at Brantwood from influenza on January 20, 1900, at age 80. He was buried in the churchyard at Coniston. His cousin, Joan Severn, who had cared for him, inherited his estate.

Ruskin's reputation declined after his death but has grown again. His home, Brantwood, is now open to the public as a museum. The Guild of St George continues its work in education and arts. Many events were held in 2019 to celebrate 200 years since his birth.

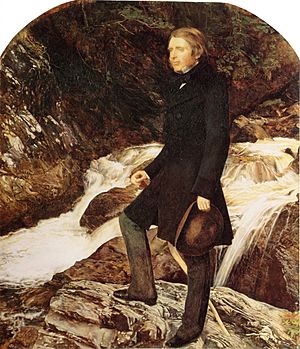

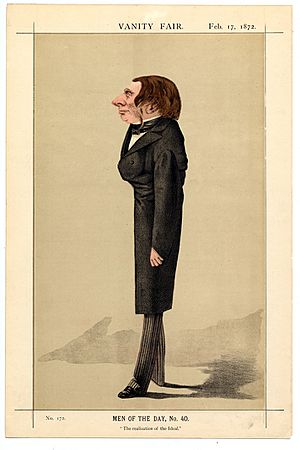

Ruskin's Appearance

In his middle age, Ruskin was described as slim with bright blue eyes. He often wore a blue neckcloth. Later in life, he grew a long beard and looked like an "Old Testament" prophet.

Ruskin's Impact

Global Influence

Ruskin's ideas spread around the world. Leo Tolstoy called him "one of the most remarkable men" and used his ideas in Russia. Marcel Proust admired Ruskin and helped translate his works into French. Mahatma Gandhi said Unto This Last had a "magic spell" on him. He rewrote it in Gujarati, calling it Sarvodaya ("The Advancement of All"). In Japan, Ryuzo Mikimoto helped translate Ruskin's work and started the Ruskin Society of Tokyo.

Some communities tried to live by Ruskin's ideas. These included Ruskin, Florida and the Ruskin Commonwealth Association in Tennessee.

Ruskin's work has been translated into many languages, including German, Italian, Spanish, Chinese, and several Indian languages.

Art, Architecture, and Literature

Many famous people in art, architecture, and literature were influenced by Ruskin. Architects like Le Corbusier and Frank Lloyd Wright used his ideas. Writers such as Oscar Wilde, G. K. Chesterton, and T. S. Eliot felt his impact. Art historians and critics also studied his work.

Craft and Conservation

William Morris and C. R. Ashbee were followers of Ruskin. Through them, Ruskin's ideas helped create the arts and crafts movement. Ruskin's ideas about protecting open spaces and old buildings inspired his friends Octavia Hill and Hardwicke Rawnsley. They helped start the National Trust, which protects historic places and natural beauty in the UK.

Society, Education, and Sport

Ruskin inspired pioneers of town planning and the garden city movement.

His educational ideas influenced schools like Bembridge School. Ruskin College in Oxford, a college for working men, was named after him.

Ruskin's collection of art for teaching, with 1470 works, is at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. The museum uses it for drawing courses.

Pierre de Coubertin, who started the modern Olympic Games, said Ruskin's ideas inspired him. He believed the games should have an "aesthetic identity" beyond just winning.

Politics and Social Change

Ruskin inspired many Christian socialists. His ideas influenced economists and social reformers. He helped inspire the settlement movement in Britain and the United States, which provided support to poor communities. Many early members of the British Labour Party said Ruskin influenced them.

Ruskin Today

In 2019, celebrations marked 200 years since Ruskin's birth.

People interested in Ruskin can visit the Ruskin Library at Lancaster University, his home Brantwood, and the Ruskin Museum in Coniston. All are open to the public. Ruskin's Guild of St George continues its work in education, arts, crafts, and farming.

Many places are named after him, including schools like The Priory Ruskin Academy and John Ruskin College. Anglia Ruskin University also traces its roots to a school where Ruskin spoke. There are also clubs and societies named after him, like the Ruskin Literary and Debating Society in Canada.

In the 21st century, scholars still study Ruskin's impact on science and tourism. His ideas on craft are seen in online communities like YouTube. His understanding of Gothic architecture has even influenced modern digital design.

Many writers and politicians today are still inspired by Ruskin. His ideas continue to be discussed and celebrated.

Ruskin's Ideas

Middle: Ruskin in middle-age, as Slade Professor of Art at Oxford (1869–1879). From 1879 book.

Bottom: John Ruskin in old age by Frederick Hollyer. 1894 print.

Ruskin wrote over 250 works. He started with art criticism but later wrote about science, geology, birds, books, the environment, myths, travel, economics, and social reform. His complete works fill 39 volumes.

Art and Design Ideas

Ruskin's early work defended J. M. W. Turner. He believed that great art should show a deep understanding of nature. Artists should reject old rules and paint what they truly see. He told artists in Modern Painters I to "go to Nature in all singleness of heart... rejecting nothing, selecting nothing and scorning nothing."

By the 1850s, Ruskin praised the Pre-Raphaelites. He believed their art would reform the art world. For Ruskin, art must show truth. It should not just be about skill, but also about the artist's moral character. He disliked Whistler's art because he felt it lacked this moral depth.

Ruskin strongly disliked Classical architecture. He believed it was "proud and unholy." He loved the Medieval Gothic style. He praised Gothic buildings for showing respect for nature and allowing workers to express themselves freely. He saw a connection between the worker, the community, nature, and God in Gothic art.

He believed that creating true Gothic architecture involved the whole community. Even the rough parts of Gothic buildings showed the "liberty of every workman." In contrast, Classical architecture seemed to him to be about strict rules and control. Ruskin connected Classical values to the problems of the industrial revolution. He criticized buildings like The Crystal Palace for being too mechanical.

Ruskin's ideas indirectly led to a revival of Gothic styles. However, he was often disappointed with the results. He felt that mass-produced Gothic buildings did not follow his true principles. Even the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, which he helped design, did not fully satisfy him.

Ruskin's dislike for strict rules and mass production led him to criticize laissez-faire capitalism. His ideas inspired the Arts and Crafts Movement and groups like the National Trust.

Art historian Kenneth Clark said Ruskin's views on art "cannot be made to form a logical system, and perhaps owe to this fact a part of their value." Ruskin's descriptions of art are very vivid and create strong images in the mind.

Protecting Old Buildings

Ruskin believed strongly in preserving old buildings. He thought that the "age" of a building was very important. He said, "the greatest glory of a building is not in its stones, not in its gold. Its glory is in its Age." He believed that old walls had a "deep sense of voicefulness" from all the people who had passed by them.

He was against simply restoring old buildings. He thought that if a building had not been cared for, it should be left to slowly decay naturally, rather than being rebuilt in a way that changed its original character.

Criticizing Economics

Ruskin criticized the economic ideas of his time. He felt they did not consider human feelings and motivations. He started sharing these ideas in The Stones of Venice and later in Unto This Last.

He was unhappy with the role of workers, especially craftsmen, in modern industrial society. He believed that the ideas of Adam Smith had led to workers feeling disconnected from their work and from each other.

Ruskin suggested that workers should be paid a fair, fixed wage. This would mean that good workers would always have jobs because of the quality of their work.

In Unto This Last, Ruskin suggested that the government should set standards for work and production to ensure fairness. He proposed government schools for training young people, government workshops for the unemployed, and pensions for the elderly. Many of these ideas were later included in the welfare state.

Key Terms from Ruskin

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) credits Ruskin with the first use or definition of many words. Here are a few:

- Pathetic fallacy: Ruskin created this term in Modern Painters III (1856). It describes when human emotions are given to non-human things. For example, saying "the sad clouds cried" when it rains.

- Fors Clavigera: This was the title of his letters to British workers (1871–84). Ruskin said the name meant three powers that shape human destiny: force (like Hercules' club), fortitude (like Ulysses' key), and fortune (like Lycurgus' nail). He believed these powers represented human talents and the ability to act at the right moment.

- Illth: Ruskin used this word as the opposite of wealth. For him, wealth meant "well-being," so illth meant "ill-being" or suffering.

Ruskin in Stories and Films

In Books

- Ruskin might have inspired characters in Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865).

- He appears as Mr Herbert in the novel The New Republic (1878).

- False Dawn (1924) by Edith Wharton features the main character meeting John Ruskin.

- John Ruskin's Wife (1979) is a novel about his marriage.

- Brantwood: The Story of an Obsession (1986) is a novel about people interested in Ruskin's home.

- The Invention of Truth (1995) is a novel where Ruskin visits Amiens cathedral.

- Come, Gentle Night (2002) is a short story about Ruskin's wedding night.

- Manly Pursuits (1999) uses Ruskin's road-mending project as a background.

- Sesame and Roses (2007) is a short story about Ruskin's love for Venice and Rose La Touche.

- Alice I Have Been (2010) is a fictional story about Alice Liddell, who inspired Lewis Carroll.

- Light, Descending (2014) is a novel about John Ruskin.

In Other Media

- The Love of John Ruskin (1912) was a silent movie about Ruskin, Effie, and Millais.

- Dante's Inferno (1967) was a TV movie where Clive Goodwin played Ruskin.

- The Love School (1975) was a BBC TV series about the Pre-Raphaelites.

- Dear Countess (1983) was a radio play about Ruskin's marriage.

- The Passion of John Ruskin (1994) was a film directed by Alex Chapple.

- Parrots and Owls (1994) was a radio play about Ruskin and Gothic architecture.

- Modern Painters (1995) was an opera about Ruskin.

- The Countess (1995) was a play about Ruskin's marriage.

- The Order of Release (1998) was a radio play about Ruskin, Effie, and Millais.

- Mrs Ruskin (2003) was a play about Ruskin's marriage.

- Desperate Romantics (2009) was a BBC drama where Tom Hollander played Ruskin.

- Mr. Turner (2014) was a film about J. M. W. Turner, with Joshua McGuire as Ruskin.

- Effie Gray (2014) was a film about the love triangle between Ruskin, Effie, and Millais.

Images for kids

-

Sunset seen from Goldau (after J. M. W. Turner)

See also

In Spanish: John Ruskin para niños

In Spanish: John Ruskin para niños

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |