History of capitalism facts for kids

Capitalism is an economic system where individuals and private businesses own most of the resources and tools used to produce goods and services. They operate these for profit. Key features include buying and selling freely, saving money to invest, trading willingly, and working for wages. How capitalism started, grew, and spread is a big topic of study and discussion.

Some people wonder if capitalism is a natural way for economies to work, or if it came from specific historical events. They also debate if it began in towns and trade, or in how land was owned in the countryside. Other discussions involve the role of different social classes, the government's part, and if capitalism is mainly a European idea. People also think about its connection to European empires and whether new technology drives capitalism or is just a side effect. Finally, there's a big question: Is capitalism the best way to organize human societies?

Contents

How Capitalism Started: Farming and Land

Changes in the 14th Century

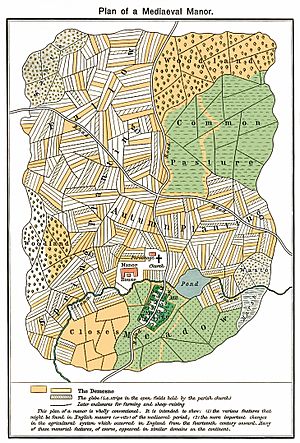

Some historians believe that modern capitalism began during a "crisis of the Late Middle Ages." This was a conflict between the rich landowners and the farmers, called serfs. The old system, called manorialism, made it hard for capitalism to grow.

Serfs had to produce food for their lords. This meant they had little reason to invent new farming tools or work together. Lords owned the land and used force to get food from serfs. Since lords were not selling their food in markets, they didn't need to innovate. Also, lords spent their money on wars or fancy things to make alliances, not on new ways to produce goods.

The population crisis of the 14th century changed everything. Farming reached its limits, bad weather caused the Great Famine of 1315–1317, and the Black Death (a terrible plague) killed many people. These events led to less food being produced.

In response, feudal lords tried to expand their lands through war. They demanded more from their serfs to pay for military costs. In England, many serfs rebelled. Some moved to towns, some bought land, and others rented land from lords who needed people to work their estates again.

This period helped set the stage for mercantilism, which was an early form of capitalism. Feudalism, which lasted until the 16th century, had self-sufficient manors. This limited markets and slowed capitalism. However, new technologies and discoveries, especially in farming and exploration, helped capitalism grow. A key change was the rise of wage earners and capitalist merchants. This competitive system, where there were winners and losers, led to mercantilism. In mercantilism, private businesses owned capital, private decisions guided investments, and competition in a free market set prices and production.

Enclosing Common Lands

By the 16th century, England was a strong, central country. Much of the old feudal system was gone. Good roads and a large capital city, London, made this centralization stronger. London was a central market for the whole country. This created a big market for goods, unlike the smaller, separate feudal areas in most of Europe.

Farming also started to change a lot. The manorial system had broken down. Land became owned by fewer landlords who had bigger and bigger estates. This system pushed both landlords and tenants to grow more food to make a profit. Since the rich landowners couldn't force peasants to give them extra food as easily, they tried better farming methods. Tenants also wanted to improve their methods to do well in the growing job market. Land rents were no longer fixed by old customs. They became directly affected by market prices.

A big part of this change was the enclosure of common land. Before, peasants had traditional rights to use these lands, like cutting hay or grazing animals. Once enclosed, only the owner could use the land. This process of enclosure became common in English farming during the 16th century. By the 19th century, most common lands were only rough pastures in mountains or small lowland areas.

Some historians say that rich landowners used their power to take public land for themselves. This created a working class with no land, who then had to work in the new factories in northern England. For example, between 1760 and 1820, many common rights were lost in villages due to enclosure. Some call enclosure a clear case of "class robbery." An anthropologist named Jason Hickel notes that this led to many peasant revolts, which were put down with violence.

Other scholars argue that wealthier peasants actually supported and took part in enclosure. They wanted to end the constant poverty of just growing enough food to survive. These scholars say that the impact of 18th and 19th-century enclosure has been "greatly exaggerated."

Early Capitalism: Merchants and Trade

How Trade Began

Trade has existed for a very long time, but it wasn't capitalism. The first records of merchants seeking profit over long distances date back to ancient Mesopotamia around 2000 BCE. The Roman Empire had advanced trade, and Islamic nations also had widespread trade networks. However, capitalism as we know it started in Europe during the late Middle Ages and Renaissance.

Early forms of commerce appeared on church lands in Italy and France, and in the independent Italian city-states during the late Middle Ages. New ideas in banking, insurance, and accounting, along with a focus on saving and reinvesting, helped these cities grow. These cities were independent from the Holy Roman Empire and the Catholic Church. They traded with North Africa, the Middle East, and Asia, bringing in new practices. They were also very different from the absolute monarchies of Spain and France, valuing freedom for their citizens.

The Rise of Mercantilism

Modern capitalism shares some features with mercantilism, which was common in Europe between the 16th and 18th centuries. Early signs of mercantilism appeared in Venice, Genoa, and Pisa, focusing on trade in gold and silver across the Mediterranean. But mercantilism truly grew around the Atlantic Ocean.

England started a big, organized approach to mercantilism during the Elizabethan Era. An early idea about a country's trade balance appeared in a 1549 book: "We must always be careful not to buy more from foreigners than we sell them, or we will make ourselves poor and them rich." Queen Elizabeth I worked to build a strong navy and merchant fleet. This was to challenge Spain's control over trade and increase England's wealth.

These efforts helped England defend itself against the much larger Spanish Empire. They also laid the groundwork for England to build a global empire later on. Important people who helped create the English mercantilist system include Gerard de Malynes and Thomas Mun. Mun's book, England's Treasure by Forraign Trade, explained the idea of a "balance of trade" in a clear way. Other thinkers like Josiah Child also developed these ideas. In France, Jean-Baptiste Colbert was a key figure in French mercantilism in the 17th century.

Main Ideas of Mercantilism

Under mercantilism, European merchants, supported by government rules, money, and special rights, made most of their money by buying and selling goods. Francis Bacon said that mercantilism aimed to "open and balance trade; encourage manufacturing; stop laziness; control waste and excess with laws; improve farming; and regulate prices." Similar economic rules had existed in medieval towns. But under mercantilism, with the rise of powerful kings, the government took over from local guilds as the main economic regulator.

A main idea of mercantilism was bullionism, which stressed the importance of collecting precious metals like gold and silver. Mercantilists believed a country should export more goods than it imported. This way, foreigners would have to pay the difference in precious metals. They argued that only raw materials that couldn't be found at home should be imported. They also promoted government help, like giving special rights and charging taxes on imports (tariffs), to encourage making goods at home.

Supporters of mercantilism believed that state power and taking over lands overseas were the main goals of economic policy. If a country couldn't get its own raw materials, mercantilists thought it should get colonies to extract them from. Colonies were not just sources of raw materials; they were also markets for finished products. To prevent competition, colonies were not allowed to manufacture goods or trade with other foreign powers.

Mercantilism was a system of trade for profit. However, goods were still mostly made using older, non-capitalist methods. Karl Polanyi noted that mercantilism, even with its focus on trade, never fully turned labor and land into simple items for sale. He argued that a truly competitive labor market in England didn't exist until 1834. So, industrial capitalism as a social system didn't really begin before that date.

Special Trading Companies

The Muscovy Company was the first big English joint stock company with a special charter. It was set up in 1555 and had a monopoly on trade between England and Russia. This company was a spin-off of an earlier group, the Company of Merchant Adventurers to New Lands, founded in 1551. This was the start of a type of business that would soon become very popular in England, the Netherlands, and other places.

The British East India Company (1600) and the Dutch East India Company (1602) started an era of large, state-chartered trading companies. These companies had monopolies on trade, given to them by the government. As chartered joint-stock companies, they had special powers, including making laws, having their own armies, and signing treaties. These powerful companies, backed by their nations, sought to gather precious metals, which often led to military conflicts. During this time, merchants, who used to trade on their own, invested money in these companies and colonies, hoping to earn a profit.

Industrial Capitalism: Factories and Machines

Mercantilism started to fade in Great Britain in the mid-18th century. New economic thinkers, like Adam Smith, questioned its basic ideas. For example, they disagreed that the world's wealth was fixed, or that one country could only get richer by making another poorer. However, mercantilism continued in less developed countries like Prussia and Russia, which had newer factories.

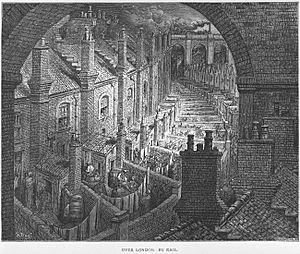

The mid-18th century saw the rise of industrial capitalism. This was possible because: 1. A lot of money had been saved up during the merchant phase of capitalism and was invested in machines. 2. The enclosures meant that many people in Britain no longer had land to farm for food. They had to buy basic goods, creating a huge market for products.

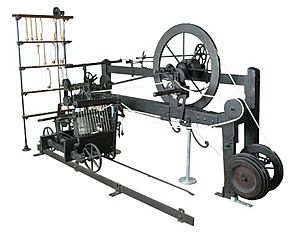

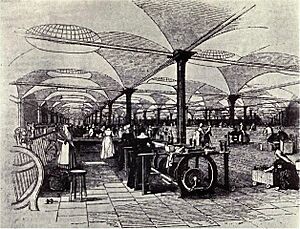

Industrial capitalism, which some say started in the late 18th century, brought about the factory system. This system involved a complex division of labor, where work tasks were broken down and done repeatedly. Industrial capitalism eventually made the capitalist way of producing goods dominant worldwide.

During the Industrial Revolution, factory owners became more important than merchants in the capitalist system. This led to the decline of traditional skills of artisans and craftsmen. Capitalism also changed the relationship between British landowners and peasants. Farming shifted from growing food for survival on a feudal manor to producing crops to sell for money. The extra money made from commercial farming encouraged more use of machines in agriculture.

There's a debate about how much Atlantic slavery helped industrial capitalism grow. Eric Williams (1944) argued in his book Capitalism and Slavery that plantation slavery was crucial for the growth of industrial capitalism, as both happened around the same time. Harvey (2019) wrote that in the 1860s, the Lancashire mills, a symbol of the Industrial Revolution, relied completely on the labor of three million cotton slaves in the American South.

The Industrial Revolution

The amount of goods produced under capitalism began to increase greatly and steadily around the start of the 19th century. This period is known as the Industrial Revolution. Starting around 1760 in England, there was a steady shift to new ways of manufacturing in many industries. This included moving from making things by hand to using machines. New chemical and iron production methods, better use of water power, more use of steam power, and the development of machine tools also played a part. It also involved changing from wood and other natural fuels to coal.

In making textiles, machines for spinning cotton, powered by steam or water, increased a worker's output by about 1000 times. This was thanks to inventions like James Hargreaves' spinning jenny, Richard Arkwright's water frame, and Samuel Crompton's Spinning Mule. The power loom increased a worker's output by over 40 times. The cotton gin made removing seeds from cotton 50 times faster. Big gains in productivity also happened in spinning and weaving wool and linen, though not as much as in cotton.

Money and Banks

As Britain's industry grew, its system of finance and credit also grew. In the 18th century, banks offered more services. They introduced ways to clear payments, invest in securities, use checks, and get overdraft protection. Checks were invented in England in the 17th century. Banks used to send messengers to the issuing bank to settle payments. Around 1770, banks started meeting in one central place. By the 19th century, a special building, called a bankers' clearing house, was set up. The London clearing house used a system where each bank paid and received cash from an inspector at the end of each day. The first overdraft service was set up in 1728 by The Royal Bank of Scotland.

After the Napoleonic War ended and trade bounced back, the Bank of England's gold reserves grew. They went from under 4 million pounds in 1821 to 14 million pounds by late 1824.

Older inventions became common parts of financial life in the 19th century. The Bank of England first issued banknotes in the 17th century, but they were handwritten and few. After 1725, they were partly printed, but cashiers still had to sign each note and make them payable to a specific person. In 1844, a law called the Bank Charter Act linked these notes to gold reserves. This created the idea of central banking and controlling money supply. The notes became fully printed and widely available from 1855.

Growing international trade led to more banks, especially in London. These new "merchant banks" helped trade grow, profiting from England's rising power in sea shipping. Two immigrant families, Rothschild and Baring, started merchant banking firms in London in the late 18th century. They became very powerful in world banking in the next century. The huge wealth these banking firms gathered soon got a lot of attention.

How banks operated also changed. At the start of the century, banking was mostly for a few very rich families. But within a few decades, a new kind of bank appeared. These banks were owned by many anonymous shareholders, run by professional managers, and received deposits from a growing number of small, middle-class savers. While this type of bank was newly prominent, it wasn't entirely new. The Quaker family Barclays had been banking this way since 1690.

Free Trade and Global Connections

During the height of the First French Empire, Napoleon tried to create a "continental system." This system aimed to make Europe economically independent, weakening British trade. It involved things like using sugar from beets instead of cane sugar imported from the tropics. Even though this made British businessmen want peace, Britain kept fighting. This was partly because it was well into the Industrial Revolution. The war actually had the opposite effect: it boosted some industries, like pig iron production, which increased from 68,000 tons in 1788 to 244,000 by 1806.

In 1817, economists like David Ricardo argued that free trade would help both strong and weak industrial countries. Ricardo's theory of comparative advantage stated: "When an inefficient producer sends the merchandise it produces best to a country able to produce it more efficiently, both countries benefit."

By the mid-19th century, Britain was fully committed to free trade. This began the first era of globalization. In the 1840s, laws like the Corn Laws and Navigation Acts were removed, starting a new age of free trade. Following the ideas of economists like Adam Smith and David Ricardo, Britain embraced classical liberalism. This encouraged competition and the growth of a market economy.

Industrialization allowed for cheap production of household items due to economies of scale (making things in large quantities reduces cost). At the same time, rapid population growth created a steady demand for goods. 19th-century imperialism greatly shaped globalization during this period. After the First Opium War and Second Opium War and Britain's conquest of India, huge populations in these regions became eager buyers of European goods. During this time, parts of Africa and the Pacific islands were brought into the global system. Meanwhile, European takeover of new parts of the world, especially sub-Saharan Africa, provided valuable natural resources like rubber, diamonds, and coal. This helped boost trade and investment between European imperial powers, their colonies, and the United States.

The global financial system was mostly linked to the gold standard during this time. The United Kingdom officially adopted this standard in 1821. Canada followed in 1853, Newfoundland in 1865, and the United States and Germany in 1873. New technologies like the telegraph, the transatlantic telegraph cable, the Radiotelephone, the steamship, and the railway allowed goods and information to move around the world faster than ever before.

When the American Civil War broke out in the United States in 1861, ports were blocked to international trade. This cut off the main supply of cotton for the factories in Lancashire, England. Textile industries then started relying on cotton from Africa and Asia during the U.S. Civil War. This created pressure for a canal through the Suez peninsula, controlled by Britain and France. The Suez canal opened in 1869, the same year the Central Pacific Railroad across North America was finished. Capitalism and the drive for profit were making the world a smaller place.

Capitalism in the 20th Century

Several big challenges to capitalism appeared in the early 20th century. The Russian Revolution of 1917 created the world's first state with a ruling communist party. A decade later, the Great Depression led to more criticism of the capitalist system. One response to this crisis was to turn to fascism, an idea that supported state capitalism (where the government controls businesses). Another response was to reject capitalism completely in favor of communist or democratic socialist ideas.

Government's Role and Free Markets

After the Great Depression and Second World War, the world's leading capitalist economies recovered quickly. This period of fast growth made people less worried about capitalism failing. Governments started playing a bigger role in managing and regulating the capitalist system in many parts of the world.

Keynesian economics, which suggests government involvement in the economy, became widely accepted. Countries like the United Kingdom even tried "mixed economies," where the government owned and ran some major industries.

Government spending also increased in the US. In 1929, total government spending was less than one-tenth of the country's total production (GNP). From the 1970s, it was about one-third. Similar increases happened in all industrialized capitalist countries. Some, like France, had even higher government spending compared to their GNP than the United States.

Many new tools in social sciences were developed to explain the social and economic changes of this time. These included ideas like "post-industrial society" and the "welfare state" (where the government provides social support).

The long period of growth after the war ended in the 1970s, with economic problems following the 1973 oil crisis. The "stagflation" (slow growth and high inflation) of the 1970s led many experts and politicians to support market-focused policies. These ideas were inspired by the "laissez-faire" (hands-off) capitalism of the 19th century, especially influenced by Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman. This new approach, called neoliberalism, was seen as an alternative to Keynesianism. It focused on fast economic growth. Market-focused solutions gained more support in the Western world, especially under Ronald Reagan in the United States and Margaret Thatcher in the UK in the 1980s. Public and political interest shifted from Keynes's managed capitalism to a focus on individual choice, called "remarketized capitalism."

According to political economist Clara E. Mattei, the three booming decades after World War II were unusual in the history of modern capitalism. She writes that austerity (strict economic policies) didn't start with the neoliberal era in the 1970s, but "has been the mainstay of capitalism."

More Global Connections

Trade with other countries has been linked to capitalism for over 500 years. However, some thinkers argue that recent trends in globalisation have made it easier for people and money to move around since the late 20th century. This has limited how much countries can choose non-capitalist ways of developing. Today, these trends support the idea that capitalism should be seen as a truly world system. But other thinkers argue that globalization, even in its size, is no greater now than during earlier periods of capitalist trade.

After the Bretton Woods system was abandoned in 1971 (which fixed exchange rates), the total value of foreign exchange transactions was estimated to be at least 20 times greater than all foreign movements of goods and services. The internationalization of finance, which some see as beyond government control, combined with how easily large companies can move their operations to countries with low wages, has raised questions about the "eclipse" of national power due to the growing "globalization" of capital.

While economists generally agree on the size of global income inequality, they disagree on whether it has recently increased or decreased. In countries like China, where income inequality is clearly growing, it's also clear that overall economic growth has rapidly increased with capitalist reforms. Indur M. Goklany's book The Improving State of the World argues that economic growth since the Industrial Revolution has been very strong. He says that things like good nutrition, longer life expectancy, lower infant mortality, higher literacy, less child labor, more education, and more free time have greatly improved.

Some scholars, including Stephen Hawking and researchers for the International Monetary Fund, argue that globalization and neoliberal economic policies are not reducing inequality and poverty but making them worse. They say these policies are creating new forms of modern slavery. Such policies are also increasing the number of displaced, unemployed, and imprisoned people, while speeding up environmental damage and species extinction. In 2017, the IMF warned that inequality within nations, despite global inequality falling in recent decades, has risen so sharply that it threatens economic growth and could lead to more political division. Rising economic inequality after the Great Recession and the anger it caused have led to a return of socialist and nationalist ideas in the Western world. This has made some economic leaders worried about the future of capitalism.

According to scholars Gary Gerstle and Fritz Bartel, with the end of the Cold War and the rise of neoliberal financialized capitalism as the main system, capitalism has become a truly global order in a way not seen since 1914. Economist Radhika Desai agrees that 1914 was the peak of the capitalist system. However, she argues that the neoliberal reforms meant to restore capitalism have instead brought increased inequalities, divided societies, economic crises, and a lack of meaningful politics, along with slow growth. She believes this shows the system is "losing ground in terms of economic weight and world influence." Gerstle argues that in the later part of the neoliberal period, "political disorder and dysfunction reign." He suggests that the most important question for the United States and the world is what comes next.

Capitalism in the 21st Century

By the start of the 21st century, mixed economies, which combine capitalist elements with some government control, had become the most common economic systems worldwide. The fall of the Soviet bloc in 1991 greatly reduced the influence of socialism as an alternative economic system. However, leftist movements are still strong in some parts of the world, especially in Latin America, with some ties to older anti-capitalist movements.

In many developing countries, the power of banks and financial capital has increasingly shaped national development plans. This has led some to suggest we are in a new phase of financial capitalism.

Government intervention in global financial markets after the financial crisis of 2007–2010 was seen by some as a sign of a crisis for free-market capitalism. Serious problems in the banking system and financial markets, partly due to the subprime mortgage crisis, reached a critical point in September 2008. This was marked by a severe lack of available money in global credit markets, which threatened investment banks and other financial institutions.

The Future of Capitalism

According to Michio Kaku, the shift to an information society might mean leaving some parts of capitalism behind. This is because the "capital" needed to create and process information becomes available to many people and is hard to control. This is closely related to the debated issues of intellectual property. Some have also guessed that the development of advanced molecular manufacturing (making things atom by atom), especially "universal assemblers," might make capitalism outdated. This is because "capital" might no longer be an important part of human economic life. Various thinkers have also explored what kind of economic system might replace capitalism.

The Role of Women

Historians who study women's roles have discussed how capitalism affected women's status. Alice Clark argued that when capitalism arrived in 17th-century England, it negatively impacted women. She said women lost much of their economic importance. Clark believed that in 16th-century England, women were involved in many parts of industry and farming. The home was a main place of production, and women played a vital role in running farms and some trades and estates. Their useful economic roles gave them a kind of equality with their husbands.

However, Clark argued that as capitalism grew in the 17th century, there was more and more division of labor. Husbands took paid jobs outside the home, and wives were left with unpaid household work. Middle-class women were confined to an idle home life, supervising servants. Lower-class women were forced to take poorly paid jobs. So, Clark believed capitalism had a negative effect on women.

In contrast, Ivy Pinchbeck argued that capitalism created the conditions for women's freedom. Tilly and Scott have highlighted the ongoing status of women, finding three stages in European history. In the time before factories, production was mostly for home use, and women made many household necessities. The second stage was the "family wage economy" of early industrialization. During this stage, the whole family depended on the combined wages of its members, including husband, wife, and older children. The third, or modern, stage, is the "family consumer economy." Here, the family is where goods are consumed, and women are widely employed in retail and office jobs to support rising living standards.

See also

In Spanish: Historia del capitalismo para niños

In Spanish: Historia del capitalismo para niños

- Brenner debate

- Capitalism and Islam

- Capitalist mode of production

- Enclosure and British Agricultural Revolution

- Fernand Braudel

- Financial crisis of 2007–2008

- History of capitalist theory

- History of globalization

- History of private equity and venture capital

- Primitive accumulation of capital

- Protestant work ethic

- Simple commodity production

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |