Manorialism facts for kids

Manorialism (also called Seigneurialism) was a way of organizing the economy in the Middle Ages. It was mostly about agriculture. Manorialism explains how land was shared and who earned money from it.

A lord was given a piece of land, usually by a higher nobleman or the king. When he got the land, he also got everything on it. This meant that most of the people living on the land also belonged to the nobleman. These people, called peasants, had to pay the lord or work for him. This way, the nobleman could live and support his family from what he received from the peasants. He also had some legal powers, like being a police force. The peasants had to give things to the lord. In return, they received protection.

The payments the peasants had to make were different. Sometimes they had to work for their lord. Other times, they had to give a part of what they grew or earned. For example, if they grew corn, the lord would get a tenth (1/10) of their harvest. This was called payment in nature or sharecropping. It was very rare for them to pay with money.

Contents

How Manors Worked

Each manor usually had three main types of land:

- Demesne: This was the land directly controlled by the lord. It was used to support his household and family.

- Dependent holdings: This land was held by serfs or villeins (peasants who were not completely free). They had to provide the lord with specific work or a part of their crops. Sometimes they paid money instead.

- Free peasant land: This land did not have the same work duties. However, it was still under the lord's rules and customs. Peasants on this land paid a fixed money rent.

Sometimes, the lord owned a mill, a bakery, or a wine-press. Peasants could use these for a fee. Also, the right to hunt or let pigs eat in the lord's woodland cost money. Peasants could use the lord's legal system to solve their problems, also for a fee. When a new person took over a land holding, they had to make a payment to the lord.

Even though they were not free, villeins were not slaves. They had legal rights based on local customs. They could also go to court, but they had to pay court fees. These fees were another way the lord made money. Over time, especially from the 13th century, peasants often paid money instead of working for the lord.

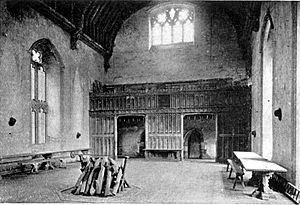

Here is a description of a manor house in Chingford, England, from a document in 1265:

He received also a sufficient and handsome hall well ceiled with oak. On the western side is a worthy bed, on the ground, a stone chimney, a wardrobe and a certain other small chamber; at the eastern end is a pantry and a buttery. Between the hall and the chapel is a sideroom. There is a decent chapel covered with tiles, a portable altar, and a small cross. In the hall are four tables on trestles. There are likewise a good kitchen covered with tiles, with a furnace and ovens, one large, the other small, for cakes, two tables, and alongside the kitchen a small house for baking. Also a new granary covered with oak shingles, and a building in which the dairy is contained, though it is divided. Likewise a chamber suited for clergymen and a necessary chamber. Also a hen-house. These are within the inner gate. Likewise outside of that gate are an old house for the servants, a good table, long and divided, and to the east of the principal building, beyond the smaller stable, a solar for the use of the servants. Also a building in which is contained a bed, also two barns, one for wheat and one for oats. These buildings are enclosed with a moat, a wall, and a hedge. Also beyond the middle gate is a good barn, and a stable of cows, and another for oxen, these old and ruinous. Also beyond the outer gate is a pigstye.

Different Kinds of Manors

Feudal society was built on two main ideas: feudalism and manorialism. But the way manors were set up could be different. In the later Middle Ages, some areas did not have a full manorial system. Also, the manorial economy changed a lot as economic conditions changed.

Not all manors had all three types of land. On average, the lord's demesne was about one-third of the farmable land. Peasant holdings were usually more. But some manors had only demesne land, and others had only peasant holdings. The number of unfree and free peasants also varied a lot. This meant that the amount of paid work needed on the lord's land was also different.

Manors also varied in their location. Most manors did not match up with just one village. Often, parts of two or more villages belonged to a manor. Or, a village might be shared between several manors. In these places, peasants who lived far from the lord's estate sometimes paid cash instead of working for the lord.

The demesne land was usually not just one big piece. It included some land around the main house and other buildings. The rest of the demesne land was in small strips spread out across the manor. Also, the lord might rent free land from nearby manors. He might even own other manors far away to get a wider range of products.

Not all manors were owned by regular lords who served in the military or paid cash to their superiors. A survey done in 1086, called the Domesday Book, showed that 17% of manors belonged directly to the king. More than a quarter (over 25%) were owned by bishops and monasteries. These church manors were usually larger. They had much more land worked by villeins than the manors owned by regular lords.

History and Where it Was Found

Today, the word "manorialism" is mostly used for medieval Western Europe. But a similar system was used in the countryside of the late Roman Empire. At that time, the number of births and the population were going down. So, workers were very important for making things. Roman leaders tried to keep the economy stable by making people stay in their social roles. Sons had to do the same job as their fathers.

People who advised the government were not allowed to quit. And coloni, who were farmers, were not allowed to leave the land they worked on. They were slowly becoming serfs. Many things led to former slaves and former free farmers becoming a dependent group called coloni. Laws made by Constantine I around 325 AD made the coloni less free and limited their rights to use the courts. Their numbers grew when barbarian foederati (allies) were allowed to settle inside the Roman Empire.

When Germanic kingdoms took over Roman rule in the West in the 5th century, Roman landowners were often simply replaced by Gothic or Germanic ones. The situation for the people on the land did not change much. The move towards villages being self-sufficient got a big push in the eighth century. This happened when normal trade in the Mediterranean Sea was stopped. Some historians, like Henri Pirenne, believe that the Arab conquests forced the medieval economy to become even more focused on rural areas. This led to the classic feudal system, where different levels of unfree peasants supported a system of local power centers.

Other pages

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Señorío para niños

In Spanish: Señorío para niños

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |