Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry facts for kids

The Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (which means The Very Rich Hours of the Duke of Berry) is a super famous and beautiful old book. It's one of the best examples of a special kind of art called manuscript illumination from the late International Gothic period.

This book is a book of hours, which is a collection of prayers people would say at certain times of the day. It was made between about 1412 and 1416 for a very rich French prince named John, Duke of Berry. He loved books and art! The main artists were three brothers known as the Limbourg brothers.

Sadly, the Limbourg brothers and the Duke of Berry all died in 1416, possibly from the plague. This meant the book was left unfinished. Later, in the 1440s, another artist (who many think was Barthélemy d'Eyck) added more to it. Then, between 1485 and 1489, a painter named Jean Colombe finished the book for the Duke of Savoy.

Today, this amazing book is kept safe in the Musée Condé in Chantilly, France. It has 206 pages made of very fine parchment, which is like thin animal skin. The pages are about 30 cm tall and 21.5 cm wide. The book contains 66 large pictures (called miniatures) and 65 smaller ones. Many artists worked on it, using expensive paints and gold, making it one of the most fancy medieval books ever.

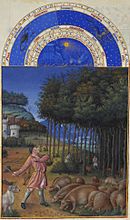

After being hidden away for about 300 years, the Très Riches Heures became very famous in the late 1800s and 1900s. Even though not many people could see the real book, its pictures helped shape how people imagine the Middle Ages. The calendar pictures are especially well-known. They show lively scenes of peasants working on farms and nobles dressed up, all with amazing medieval buildings in the background.

Contents

Who Owned This Amazing Book?

The "Golden Age" for books of hours in Europe was from 1350 to 1480. These books became very popular in France around 1400. Many great French artists worked on making them beautiful.

The Duke of Berry: A Prince Who Loved Art

John, Duke of Berry, was the French prince who ordered the Très Riches Heures. He was the third son of the French king, John the Good. We don't know much about his schooling, but he grew up surrounded by art and books. The young prince lived a very fancy life, often needing to borrow money. He ordered many artworks and collected them in his big house.

When the Duke of Berry died in 1416, people made a list of everything he owned. This list described the unfinished book as the "très riches heures" (meaning "very rich hours"). This helped tell it apart from the 15 other books of hours he owned, like the Belles Heures ("beautiful hours") and Petites Heures ("little hours").

The Book's Journey Through Time

The Très Riches Heures has had many owners since it was made. After the Duke of Berry died in 1416, its path isn't very clear until 1485.

Duke Charles I of Savoy got the book, probably as a gift. He then asked Jean Colombe to finish it around 1485–1489. Later, the book belonged to Margaret of Austria, Duchess of Savoy (1480–1530).

After that, its story is a mystery until the 1700s. That's when it got its current bookbinding with the symbols of the Serra family from Genoa, Italy.

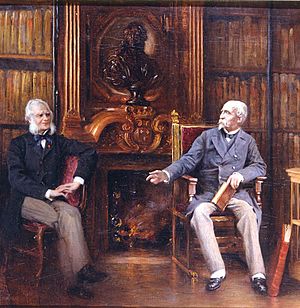

The book was then passed down to Baron Felix de Margherita. In 1856, a French prince named Henri d'Orléans, Duke of Aumale, who was living in England at the time, bought it from the baron. When he returned to France in 1871, he put the book in his library at the Château de Chantilly. He later gave his castle and library to a special French organization, making it the home of the Musée Condé.

How the Book Became Famous

When the Duke of Aumale first saw the book, he recognized it as one of Berry's commissions. He showed it to an art historian named Gustav Friedrich Waagen, who wrote about it in his book in 1857. This was the start of its rise to fame.

In 1881, a librarian named Léopold Victor Delisle figured out that this was the "très riches heures" mentioned in the Duke of Berry's 1416 inventory. This discovery was published in 1884 and has been accepted ever since.

The book became more and more famous and was reproduced often. The first color copies appeared in 1940. In 1948, the popular American magazine Life published big pictures of the 12 calendar scenes. Today, the real book is not usually on public display at the Musée Condé. Instead, visitors see copies, because the book became famous mostly through its amazing pictures.

Who Painted the Pictures?

There has been a lot of discussion about who painted the Très Riches Heures and how many artists worked on it.

The Limbourg Brothers

In 1884, Léopold Delisle connected the book to a description in the Duke of Berry's inventory. It mentioned "several gatherings of a very rich book of hours, richly illustrated and illuminated, that Pol [Paul] and his brothers made." This led to the Limbourg brothers – Paul, Jean, and Herman – being recognized as the main artists.

The three Limbourg brothers had worked for the Duke of Berry's brother before coming to work for Berry. By 1411, they were permanent members of the Duke's household. They also made another of Berry's books, the Belles Heures. It's believed the Limbourg brothers worked on the Très Riches Heures from about 1412 until their deaths in 1416. Records from 1416 show that Jean, then Paul and Herman, died. The Duke of Berry died later that same year. Other artists or assistants likely did the writing, border decorations, and gilding (adding gold).

Jean Colombe: The Finisher

One page (folio 75) of the Très Riches Heures shows Duke Charles I of Savoy and his wife. They got married in 1485, and the Duke died in 1489. This means this page wasn't part of the original book. The artist who added to the book was identified as Jean Colombe. He was paid by the Duke of Savoy to finish certain parts.

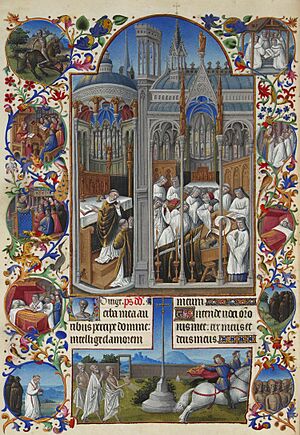

Some pictures were not complete and needed finishing, like the people and faces in the picture showing the Funeral of Raymond Diocrès.

You can see differences between the pictures by the Limbourgs and Colombe. Colombe often put his large pictures in frames of marble and gold columns. His faces are less delicate and have stronger features. He also used a very bright blue paint in some landscapes. Colombe worked in his own style and didn't try to copy the Limbourgs. On folio 75, he included a picture of one of his patron's castles in the background, just like the Limbourgs did.

The Middle Painter

An "intermediate painter," sometimes called the Master of the Shadows, is thought to be Barthélemy van Eyck. This artist likely worked on the book sometime between 1416 and 1485. Some details in the clothing of figures in the calendar pictures suggest they were painted around 1420 or even mid-1400s, after the Limbourgs. It's believed this artist was connected to King Charles VII's court, who owned the book after Berry's death.

What Is a Book of Hours For?

A breviary is a book of prayers and readings, usually for priests. A book of hours is a simpler version made for everyday people to use. The prayers were meant to be said at certain times of the day and night, called canonical hours. This regular schedule of prayers gave the book its name.

A book of hours contains prayers and religious exercises. The order of these parts could be changed for the person who owned the book or the region they lived in. The Hours of the Virgin were considered the most important part and usually had the most beautiful pictures. The Très Riches Heures is special because it has many illustrations.

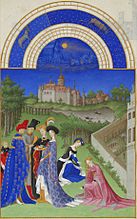

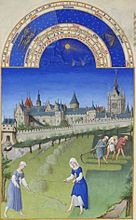

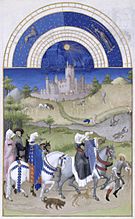

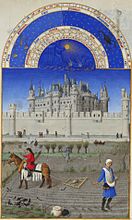

Calendar Pictures

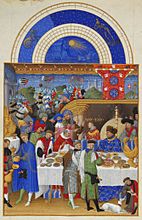

The calendar section of the book is very famous. Each month has a beautiful, large picture showing scenes of daily life or noble activities, often with one of the Duke's castles in the background. These pictures are very detailed and show what life was like for both nobles and peasants.

-

June

Palais de la Cité and the Sainte Chapelle -

August

Falconry, Château d'Étampes

Each calendar picture also has a special part at the top showing the sun, the signs of the zodiac, and numbers for the days of the month. The January picture is the largest and shows the Duke of Berry at a New Year's Day feast.

The pictures often show the Duke, his fields, his castles, or places he visited. This shows how personal and special the book was for him.

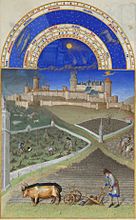

For example, the September picture was likely painted in two stages. First, the sky and castle were painted around 1438-1442. Then, Jean Colombe finished the grape-picking scene in the foreground. Artists usually started with the background, then painted the people, and finally added their faces.

In the foreground of the September picture, people are picking grapes. Some young peasants are gathering purple bunches, while one tastes the grapes. Another person carries a basket towards a mule loaded with two large baskets. The grapes are being put into the mule's baskets or into big tubs on a cart pulled by two oxen.

In the background is the Château de Saumur with its chimneys and weather vanes decorated with golden fleurs-de-lys. This castle belonged to Yolande d’Aragon, who was important in the court of King Charles VII. The castle's design is very grand and looks like something from a fairy tale.

In the middle of the grape pickers, one person is showing their behind. This funny detail is a big contrast to the elegant castle. Jean Colombe's peasants in this picture don't look as dignified as those in other parts of the book.

How Was It Made?

The Vellum Pages

The 206 pages of the book are made from very good quality calfskin, which is a type of vellum. All the pages are perfect rectangles, cut from the very center of large skins. This means the original skins were huge! The pages are 30 cm tall and 21.5 cm wide. There are very few tears or natural flaws in the vellum, showing its high quality.

The Colorful Pictures

The colors used were mixed with water and thickened with natural gums like gum Arabic. The artists used about ten different shades, plus white and black. To create such detailed work, they must have used extremely tiny brushes and probably even a magnifying glass.

What's Inside the Book?

The contents of the book are typical for a book of hours, but the huge number of beautiful pictures is very unusual.

- The Calendar: Pages 1–13

* This section has a general calendar of church holidays and saint's days. The pictures for each month are very special because of their size and detail. They show scenes from the Duke's court and his peasants working. Each picture has a top section showing the sun, zodiac signs, and days of the month.

- Anatomical Zodiac Man: Page 14

* This picture comes after the calendar. It shows the twelve signs of the zodiac over the matching parts of a human body. It also has the Duke of Berry's coat of arms. This kind of picture is not found in other books of hours, but the Duke was interested in astrology.

- Readings from the Gospels: Pages 17–19

- Prayers to the Virgin: Pages 22–25

- Fall of Man: Page 25

* This part shows the story of the Fall of Man in four stages within one picture. It's thought that Jean de Limbourg painted this, and it might have been meant for a different book originally.

- Hours of the Virgin Matins: Pages 26–60

* This section has pictures showing the Life of the Virgin Mary, including the Rest on the Flight to Egypt by Jean Colombe.

- Psalms: Pages 61–63

* The pictures for the psalms show a very direct interpretation of the words, which was rare for the time.

- The Penitential Psalms: Pages 64–71

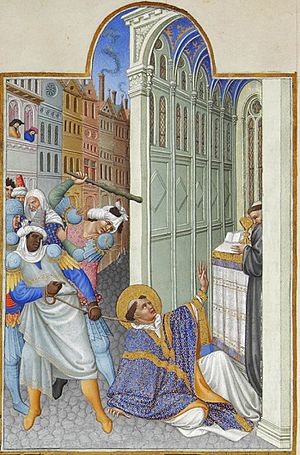

* This section starts with the "Fall of the Angels." The Limbourgs might have seen a similar painting from the 1300s. This picture also might not have been planned for this book originally. The end of this section has a two-page picture of the Procession of Saint Gregory showing the skyline of Rome.

- Hours of the Cross: Pages 75–78

* In this section, Jesus is shown as the Man of Sorrows, with his wounds and surrounded by things from his suffering. This was a common type of image in books from the 1300s.

- Hours of the Holy Ghost: Pages 79–81

- Office of the Dead: Pages 82–107

* Colombe painted all the pictures in this section, except for "Hell," which was done by a Limbourg brother. The "Hell" picture is based on a description from an Irish monk named Tundale from the 1200s. This picture might also not have been originally planned for the book. * The funeral picture shows a famous event at the funeral of Raymond Diocres, a preacher in Paris. It was said that during his funeral service, he lifted his coffin lid and told everyone, "I have been condemned to the just judgment of God."

- Short Weekday Offices: Pages 109–140

* The Presentation of the Virgin picture takes place in front of Bourges Cathedral, which was in Berry's main city.

- Plan of Rome: Page 141

- Hour of the Passion: Pages 142–157

- Masses for the Liturgical Year: Pages 158–204

* Page 201 shows the death of Andrew the Apostle. This picture was very important to the Duke of Berry because he was born on Saint Andrew's Day in 1340.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Las muy ricas horas del Duque de Berry para niños

In Spanish: Las muy ricas horas del Duque de Berry para niños