Miniature (illuminated manuscript) facts for kids

A miniature is a small, detailed picture or drawing used to decorate old handwritten books, called illuminated manuscripts. The word "miniature" comes from the Latin word miniare, which means "to color with minium". Minium was a bright red paint often used in early illustrations.

These small pictures were first found in ancient and medieval books. Over time, the word "miniature" also started being used for other small paintings, like tiny portraits.

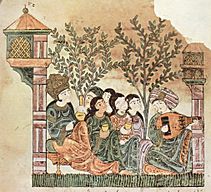

Besides the traditions in Europe, the Byzantine Empire, and Armenia, there are also amazing miniature traditions in Asia. These include Arabic, Persian, Mughal, and Ottoman miniatures. These Asian miniatures often tell stories and were sometimes kept in special albums, not just in books.

Christian Miniature Art

Early Miniatures in Italy and Byzantium (3rd–6th Centuries)

Some of the oldest surviving miniatures come from the 3rd to 6th centuries. Many early illustrated books were lost or damaged over time. For example, the Chronograph of 354 had many drawings, but the original is gone. The Cotton Genesis was mostly destroyed in a fire.

However, we still have some colored miniatures from the Ambrosian Iliad, a 5th-century book about the Greek story of the Iliad. These pictures show good drawing skills, similar to classical Roman art. They even tried to show landscapes, like the paintings found in ancient Roman homes.

The miniatures in the Vergilius Vaticanus, a book of Virgil's poems from the early 5th century, are even better preserved. They are larger and show how artists worked. They would paint the background first, then add bigger figures, and finally smaller details on top. They also used horizontal zones to create a sense of perspective.

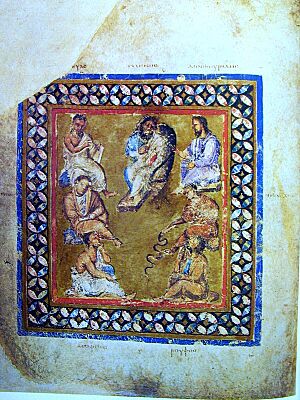

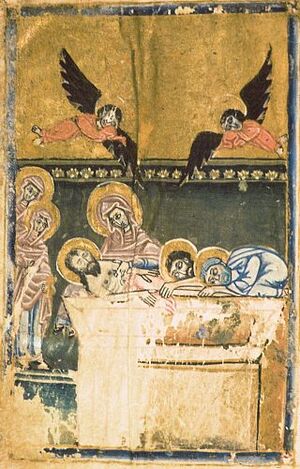

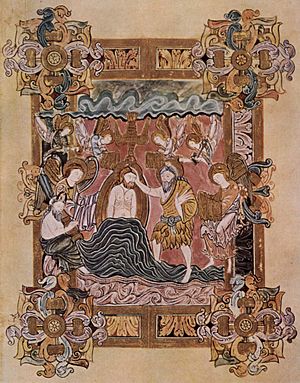

Later, the Byzantine artists started to use more specific styles. While their early works still had a classical feel, Byzantine art became more focused on religious themes. Figures often looked thin and stiff, and colors like browns and blue-greys were common. They also started painting flesh tones over a dark base, a technique later used by Italian artists.

Byzantine miniatures were known for their bright gold backgrounds. This shiny gold became very popular in Western European paintings later on. Byzantine art had a big influence on early Italian art, especially seen in church mosaics.

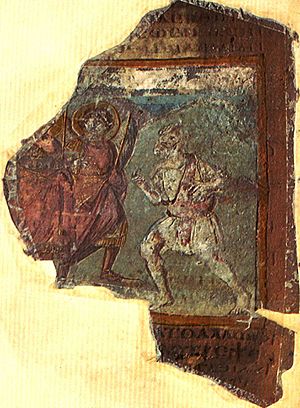

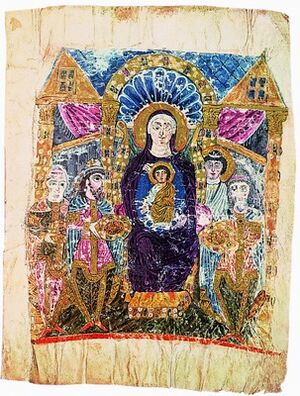

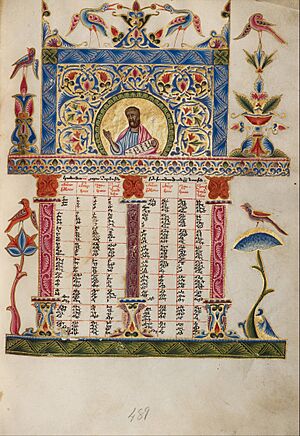

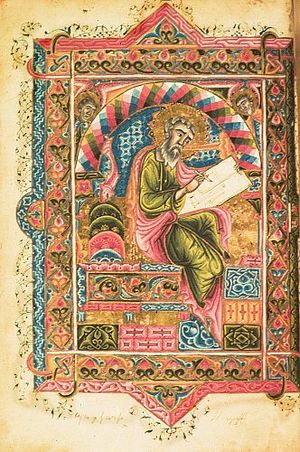

Armenian Miniature Art

Armenian miniature painting is famous for its many styles. After Mesrop Mashtots created the Armenian alphabet in 405 AD, Armenian manuscripts and miniatures began to develop. Most of the 25,000 Armenian manuscripts that still exist are decorated with these small paintings.

While many books had religious content, Armenian artists, also called "flourishers," often added scenes from everyday life. They would include images of plants, animals, hunting, and even city life in the decorative letters or margins. These details help us understand medieval Armenian life, clothes, and crafts. Some artists even painted self-portraits!

Many centers for miniature painting existed in Armenia, like Ani, Gladzor, and Tatev. Each had its own unique style. Armenian miniature art was especially strong in the 13th century, particularly in Cilician Armenia, where the miniatures were very fancy and elegant. Famous artists like Toros Roslin created beautiful works that are still admired today.

Armenian miniature painting has survived many challenges, showing the amazing creativity of the Armenian people. Its unique style, bright colors, and rich details make it a special part of world art.

The Gospels were the most popular books to illustrate, followed by the Bible. The earliest Armenian miniatures we have are from the 6th-7th centuries. They show similarities to early Christian art, including arches and elements of Hellenistic (ancient Greek) art.

In the 13th century, before the Mongol invasions, miniature painting thrived in Greater Armenia. It reached new heights in Cilician Armenia. Books became smaller, and artists started showing more realistic scenes and influences from neighboring countries like Byzantium.

Later, the Tatev School of Miniature Painting became famous. However, by the 17th-18th centuries, printed books began to replace handwritten ones, and miniature painting slowly declined.

European Miniatures (8th–12th Centuries)

In Western Europe, early miniatures were mostly about decoration. In the Merovingian period and in places like Spain and the British Isles, figures were often just part of the design, not realistic human forms.

The Anglo-Saxon school, especially in England, focused on fine outline drawings. These drawings were influenced by classical Roman art and had a lasting impact on English miniatures.

Under the Carolingian rulers, a new style developed, inspired by Byzantine art. Miniatures appeared in two main forms:

- Formal portraits: These showed figures like the Four Evangelists or emperors. They were very formal, brightly colored, and often set in architectural backgrounds without real landscapes.

- Illustrations: These showed scenes from the Bible. They were more free and copied Roman styles.

The Carolingian style influenced Anglo-Saxon artists, leading to more use of opaque colors and gold. The Benedictional of St. Æthelwold is an example of this mix of native drawing style and foreign painting techniques. However, after the Norman Conquest, this unique Anglo-Saxon style faded away.

In the 12th century, art saw a big boost. Artists became very skilled at borders and initial letters. Miniatures also showed strong drawings with bold lines and careful details. Artists improved their figure drawing, and while many subjects were repeated, some artists created truly noble miniatures.

The Norman Conquest connected England more directly with European art. This led to a strong connection between French, English, and Flemish art, creating magnificent illuminated manuscripts in northwestern Europe from the late 12th century onwards.

However, real landscapes were still missing. Artists often used solid gold backgrounds to make the figures stand out. Sacred figures continued to wear traditional robes, while other people in the scenes wore the clothes of the time.

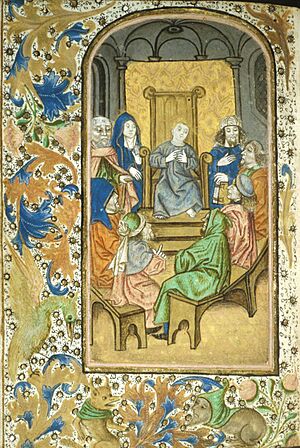

European Miniatures (13th–15th Centuries)

By the 13th century, miniatures became much smaller and more precise. Books changed from large folios to smaller sizes like octavos. There was a greater demand for books, but vellum (animal skin used for pages) was limited. Artists tried to save space, making figures small and delicate. Backgrounds were often bright with color and shiny gold.

English miniatures were often the most graceful, while French ones were neat and accurate. Flemish miniatures were less refined but stronger. English artists preferred lighter colors, while French artists loved deeper shades like ultramarine blue. Flemish and German artists used less pure colors. French manuscripts often used a reddish-gold, different from the paler gold in England and the Low Countries.

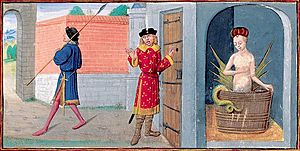

Throughout the 13th century, miniature art kept its high quality. The Bible and Psalter (a book of psalms) were very popular, so artists often repeated the same religious scenes. However, as secular (non-religious) books like romances became popular, artists had more freedom to create new illustrations.

In the 14th century, the style changed again. Lines became more flowing and delicate, creating graceful, swaying figures. Miniatures started to become more like independent pictures, focusing on their own artistic beauty rather than just being part of the book's decoration. They also became more prominent on the page.

Backgrounds became more detailed and brilliant, often with shiny gold patterns. Gothic arches and other architectural elements were added, reflecting the architecture of the time.

English drawing in the early 14th century was very graceful. French art remained precise and vivid. Art from the Low Countries and Germany was often heavier or more mechanical. As the century progressed, French miniatures became very dominant, known for their bright colors. The English school declined, partly due to political issues and wars with France.

Towards the end of the 14th century, English miniature painting saw a revival, possibly influenced by the Prague school of art. This new English style featured rich colors and carefully modeled faces, different from the simpler French style.

However, this English revival didn't last. By the mid-15th century, native English miniature art mostly ended. This was partly due to the Wars of the Roses and the rise of foreign artists. The history of miniatures in the 15th century largely focuses on Continental Europe.

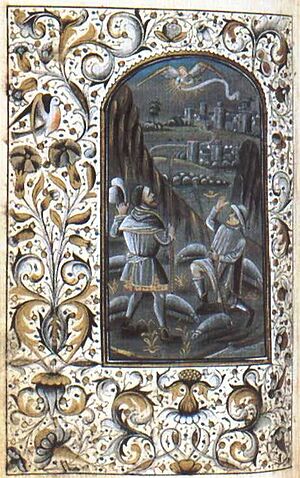

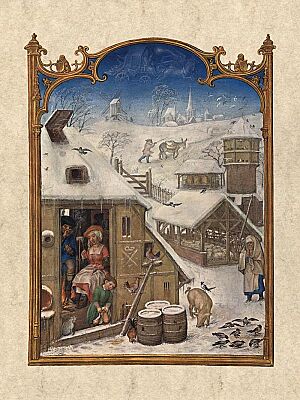

In northern France and the Low Countries, miniatures in the 15th century showed more freedom in composition. Artists focused on the overall effect of colors rather than just neat drawing. Many different types of books were illustrated, not just religious ones. The Horae, or Book of Hours, became very popular. These were personal prayer books, and their illustrations were often some of the finest miniature works. The demand for illuminated manuscripts led to a regular trade, and production was no longer limited to monasteries.

Early in the 15th century, old landscape styles and gold backgrounds were still used. But by the second quarter of the century, natural scenery became more common, though perspective was still a challenge. It took another generation for artists to truly understand horizons and atmospheric effects.

French and Flemish miniatures were similar for a while, but after the mid-15th century, their styles became more distinct. French miniatures started to decline, while the Flemish school reached its peak. Flemish miniatures were known for their extreme softness, deep colors, and careful details in clothing and facial expressions. This high quality continued into the early 16th century.

Some miniatures were done in grisaille, using only shades of grey. Without color, artists paid even more attention to details, especially in the strong, angular lines of clothing.

Italian Miniatures (13th–15th Centuries)

The Italian miniature tradition grew alongside the Flemish one in the 15th century. In the 13th and 14th centuries, Italian manuscripts showed a strong influence from Byzantine art. They often used opaque paints and relied on color alone for effect, rather than the mix of color and gold seen in France. Italian artists were known for their vivid scarlet color. Their figure drawing was less realistic than in northern Europe, often showing thick-set human forms.

However, with the Renaissance in the 15th century, Italian miniatures became top-notch, competing with the best Flemish works. They used thicker paints to create a hard, polished surface and kept sharp outlines while still having rich, deep colors.

The Italian style influenced manuscripts in southern France and even northern France. Like Flemish miniatures, Italian miniatures continued to be made successfully into the 16th century, especially for special patrons. But with the rise of printed books, the need for miniaturists eventually ended.

Other Miniature Traditions

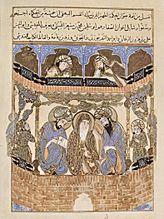

Even though Islam generally avoids pictures of people, Persia and other Islamic regions continued a tradition of illustrating books. While Arabic miniatures were less common for figures, luxury Islamic manuscripts, including the Quran, were often decorated with complex geometric patterns and designs. This is known as "illumination."

Arabic Miniatures

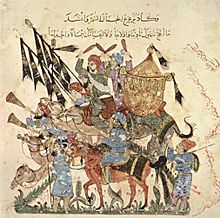

Arabic miniatures are small paintings on paper, usually found in books or as separate artworks. The earliest known example is from around 690 AD. This art form became very popular between 1000 and 1200 AD in the Abbasid Caliphate.

Arabic miniatures were influenced by Chinese and Persian styles, especially after the Mongol invasions. Most other Islamic miniatures, like Persian, Ottoman, and Mughal, were inspired by Arabic miniatures. Arab rulers were the first to ask for illuminated manuscripts.

Famous Arabic miniaturists include Ismail al-Jazari, who illustrated his own book about clever machines. Another important artist was Yahya Al-Wasiti, who lived in Baghdad in the 12th-13th centuries. He illustrated the book Maqamat, which tells funny stories about a man who tricks people across the Arabic world.

Today, most surviving Arabic manuscripts are in Western museums.

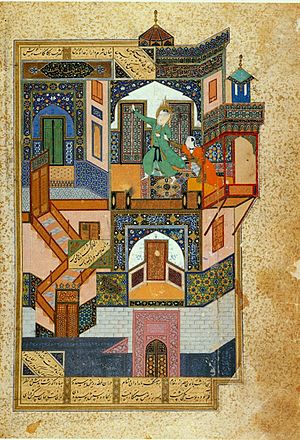

Persian Miniatures

Persian art has a long history of using miniatures for illustrated books and as single artworks collected in albums. The Mughal miniature tradition in India was heavily influenced by Persia.

Reza Abbasi (1565–1635) is considered one of the most famous Persian painters. He specialized in Persian miniatures, often painting realistic subjects. His works can be found in major museums around the world.

In 2020, UNESCO recognized the miniature art of Azerbaijan, Iran, Turkey, and Uzbekistan as an important part of humanity's cultural heritage.

Indian Miniatures

Miniature painting came to India under the Pala Dynasty, with paintings on Buddhist palm leaf manuscripts. An early example is the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā from 985 AD. This art inspired Nepalese, Tibetan, Hindu, and Jain miniature traditions later on.

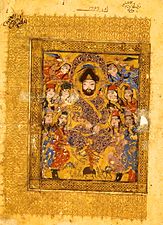

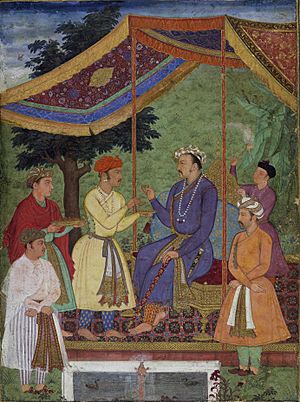

Mughal painting developed during the Mughal Empire (16th-18th centuries). These were usually miniatures for books or single paintings for albums. It started with Persian artists who came to India, but soon Hindu artists made the colors brighter and the compositions more natural. Mughal paintings often showed literature, history, portraits of court members, and nature studies. At its best, Mughal painting combined Persian, European, and Indian art styles.

In the Muslim Deccan sultanates, miniature styles also emerged, influenced by Persia and existing Hindu painting. Deccan painting was freer and more colorful than Mughal painting. As the Mughals conquered these areas, artists spread out. A version of the Mughal style then spread to princely courts in North India, especially in Rajput painting, where many different styles developed. By the 18th century, Rajput courts were creating some of the most innovative Indian paintings.

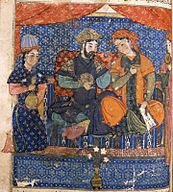

Ottoman Miniatures

The Ottoman Empire's miniature tradition began with Persian influence. Ottoman rulers greatly admired Persian miniatures. Soon, a unique Ottoman style developed, which focused more on telling stories and recording the empire's history. Ottoman illumination was also widely used in court manuscripts.

Fake Miniatures

Sometimes, miniatures are faked. Forged Islamic miniatures, often showing scientific advancements, are made by Turkish artisans as souvenirs. These can sometimes be found online or in learning materials. Medieval European miniatures have also been faked to trick collectors, with one famous forger being the "Spanish Forger."

See also

In Spanish: Miniatura para niños

In Spanish: Miniatura para niños

- Commentary on the Apocalypse by Beatus

- Book of Job in Byzantine illuminated manuscripts

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |