Insular art facts for kids

Insular art, also called Hiberno-Saxon art, is a special type of art made in Great Britain and Ireland after the Roman Empire ended. The word "Insular" comes from the Latin word insula, which means "island." During this time, Britain and Ireland shared a similar art style that was different from the rest of Europe. Art experts often see Insular art as part of the Migration Period art and early medieval art in the West. This mix of traditions gives it its unique look.

Most Insular art came from the Irish monasteries of Celtic Christianity. It also included metalwork made for important leaders. This art style began around 600 AD, mixing Celtic and Anglo-Saxon styles. A key feature is the interlace decoration, like the patterns seen at Sutton Hoo. This style was used to decorate new items, especially books called codices.

The best time for this art style ended when Viking raids started in the late 700s. These raids likely stopped work on the famous Book of Kells. No later Gospel books are as richly decorated as the masterpieces from the 700s. In England, the style blended into Anglo-Saxon art around 900 AD. But in Ireland, it continued until the 1100s, when it mixed with Romanesque art. Ireland, Scotland, and the kingdom of Northumbria in Northern England were the main places for this art. But examples were also found in southern England, Wales, and even in Europe, especially in places founded by Irish and Anglo-Saxon missionaries. Insular art influenced all later European medieval art, especially the decorations in Romanesque and Gothic books.

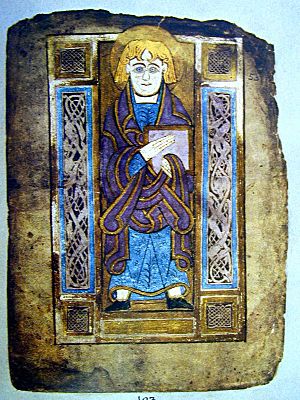

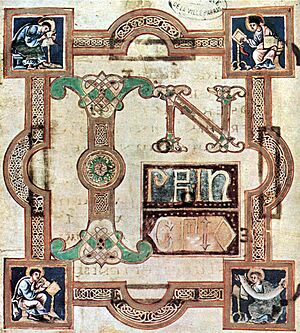

The Insular art we still have today includes illuminated manuscripts (decorated books), metalwork, and stone carvings, especially tall stone crosses. Surfaces are covered with detailed patterns, without trying to show depth or distance. Some of the best examples are the Book of Kells, Lindisfarne Gospels, Book of Durrow, brooches like the Tara Brooch, and the Ruthwell Cross. Special "Carpet pages" are common in Insular books. Also popular are historiated initials (decorated first letters), canon tables, and pictures of people, especially Evangelist portraits.

Contents

What Is Insular Art?

The term "Insular" first described the style of writing called Insular script. It is also used for a group of Insular Celtic languages. At first, it mainly described the decoration in illuminated books, which are the most common surviving items. Now, it is used for all types of Insular art. This term helps show that the art styles across Britain and Ireland were connected. It also avoids using the term "British Isles", which can be a sensitive topic in Ireland. It also helps avoid arguments about where the style began or where specific artworks were made.

Some experts say the "wider period" for Insular art was from the 400s to the 1000s. This was from when the Romans left until the Romanesque style began. A "more specific phase" was from the 500s to the 800s. This was between the time people became Christian and when the Vikings settled. However, some say that in Ireland, the Insular style lasted until the Anglo-Norman invasion in 1170. Some examples even appear as late as the 1200s and 1300s.

Insular Art Decoration

Insular art is famous for its very detailed and creative decorations. These designs use ideas from older art styles. Late Iron Age Celtic art, also known as "Ultimate La Tène", brought the love of spirals, triskeles (three-part spirals), circles, and other geometric shapes. These were mixed with animal forms, which likely came from the Germanic "animal style" found across Europe and Asia. Celtic art also used animal heads at the end of scrolls.

Interlace patterns were used in both Celtic and Germanic traditions, as well as in Roman art (like floor mosaics). Insular art took interlace to a new level, combining it with other elements. In book paintings, there is no attempt to show depth. All the focus is on a brightly patterned surface. In early works, human figures looked geometric, like animals. But over time, more classical ways of showing people appeared. These likely came from southern Anglo-Saxon areas, though northern areas also had direct links with mainland Europe.

How Insular Art Began

Unlike art from other major periods, Insular art did not come from a society where one style was used for many different objects. The islands were mostly rural, buildings were simple, and there was no Insular style of architecture. Even though many other art objects made of materials that don't last long have disappeared, it's clear that both religious and non-religious leaders wanted amazing, detailed objects. These objects would have looked even more amazing because the world around them was not very fancy.

Especially in Ireland, church leaders and powerful families were often very close. Some Irish abbey leaders came from the same family for many generations. Ireland was divided into many small "kingdoms." In Britain, there were fewer, larger kingdoms. Both the Celtic (Irish and Pictish) and Anglo-Saxon leaders had long traditions of making very fine metalwork. Much of this was used for jewelry for both men and women.

The Insular style began when these two styles, Celtic and Anglo-Saxon animal style, met in a Christian setting. They also knew a bit about later Roman art. This was especially true when they started decorating books, which were new objects for both traditions, as well as metalwork.

The Kingdom of Northumbria played a key role in forming this new style. This northern Anglo-Saxon kingdom grew into areas with Celtic people. But it often left those people mostly untouched in places like Dál Riata, Elmet, and the Kingdom of Strathclyde. The Irish monastery at Iona was started by Saint Columba in 563 AD. At that time, Iona was part of Dál Riata, which included land in both Ireland and modern Scotland.

The first Northumbrian king, Edwin, became Christian in 627 AD because of missionaries from Rome. But the Celtic Christianity from Iona was more important in Northumbria at first. Iona started Lindisfarne on the eastern coast in 635 AD. However, Northumbria stayed in touch with Rome. Other important monasteries were started by Wilfrid and Benedict Biscop, who looked to Rome. At the Synod of Whitby, the Roman ways were chosen, and the Iona group left. They didn't adopt the Roman Easter date until 715 AD.

What experts thought about the style's origins might change. This is because of many decorated metal objects found in the Staffordshire Hoard in 2009. Also, the Prittlewell princely burial from Essex, found in 2003, is being studied.

Insular Metalwork

Christianity did not encourage burying items with the dead. So, we have more pre-Christian Anglo-Saxon items than later ones. Most Christian-era items that survive were found in places that suggest they were quickly hidden, lost, or left behind. There are a few exceptions, like arm-shaped containers for holy items and portable book-shaped or house-shaped shrines for books or relics. Some of these have been owned continuously, mostly by churches in Europe. The Monymusk Reliquary has always been in Scotland.

It seems that most surviving items are just lucky finds. We only have small pieces of some types of objects, especially the largest ones. The best quality items that survive are either fancy jewelry, probably for men, or tableware or altarware. These often had very similar styles. Some pieces are hard to tell if they were for an altar or a royal dining table. It's likely that the finest church items were made by workshops that also worked for kings. But some pieces were made by monastery workshops.

Evidence suggests that Irish metalworkers made most of the best pieces. However, the items found at the royal burial at Sutton Hoo, in eastern England, are as fine as any Irish pieces. Even if we don't count workshops from later periods, the craftsperson might not have always designed the whole piece. For example, some parts of the Ardagh Chalice show less skill than the rest.

There are many large penannular brooches (brooches shaped like a ring with a gap). Several are as good as the Tara brooch. Most of these are in museums in Britain and Ireland. Each design is unique, and the work is excellent. Many design elements are similar to those used in books. Almost all metalwork techniques known can be found in Insular work. The stones used for decoration are semi-precious, like amber and rock crystal. Colored glass, enamel, and millefiori glass (probably imported) were also used, like in the 500s Ballinderry Brooch.

The gilt-bronze Rinnegan Crucifixion Plaque (late 600s or early 700s) is the most famous of nine Irish metal Crucifixion plaques. Its style is similar to figures on many high crosses. It might have been from a book cover or part of a larger altar decoration or high cross.

The Ardagh Chalice and the Derrynaflan Hoard (found in 1980) are the best church metalware pieces that survive. These pieces are thought to be from the 700s or 800s. But most metalwork dates are uncertain and come from comparing them to books. Only small pieces remain from what were probably large church items, like shrines and crosses, often with metalwork on wooden frames. The Insular crozier (a bishop's staff) had a special shape. The ones that survive, like the Kells Crozier and Lismore Crozier, seem to be Irish or Scottish and from later in the Insular period. These later works, including the 1000s River Laune and Clonmacnoise Croziers, are heavily influenced by Viking art. They have interlace patterns in the Ringerike or Viking art#Urnes-styles.

The Cross of Cong is a 1100s Irish processional cross and container for holy items. It shows Insular decoration, possibly added to bring back the old style.

It's hard to imagine what a major abbey church looked like in the Insular period. One thing that seems clear is that the most decorated books were used as display items, not just for reading. The Book of Kells, the most decorated of all, has several mistakes that were not fixed. The headings needed for the Canon tables were not added. When it was stolen in 1006 for its precious metal cover, it was taken from the sacristy (where church items are kept), not the library. The book was found, but not its cover, which also happened with the Book of Lindisfarne. None of the main Insular books still have their fancy jeweled metal covers. But we know from old writings that these covers were amazing.

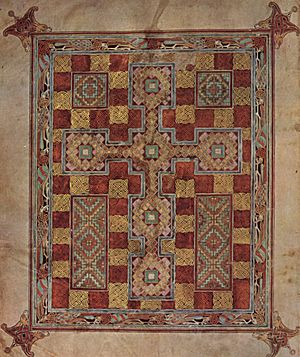

The re-used metal back cover of the Lindau Gospels (now in New York) was made in southern Germany in the late 700s or early 800s. It shows strong Insular influence. It might be the best idea of what the original covers of the great Insular books looked like. Also, a gold and garnet piece from the Anglo-Saxon Staffordshire Hoard, found in 2009, might be the corner of a book cover. The Lindau design has a cross, but the whole surface is decorated with interlace patterns between the arms of the cross. The cloisonné enamel shows Italian influence and is not found in art from the Insular homelands. But the overall look is very much like a carpet page.

-

The Tara Brooch, around 710 to 750 AD.

-

The Derrynaflan Chalice, 700s or 800s.

-

Cumdach for the Stowe Missal, around 1026.

Insular Manuscripts (Books)

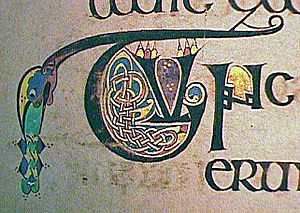

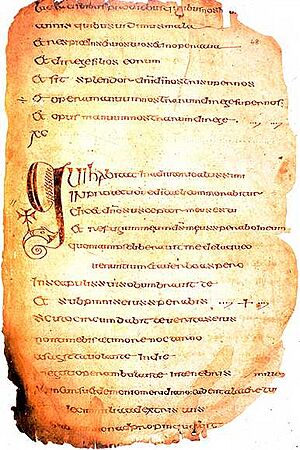

Cathach of St. Columba This Irish Latin psalter (book of Psalms) from the early 600s might be the oldest known Irish book. It only has decorated letters at the start of each Psalm, but these already show special features. Not just the first letter, but the first few letters are decorated, getting smaller as they go. The decoration changes the shape of the letters, and different decorative forms are mixed in a very non-classical way. Lines already tend to spiral and change shape. Besides black, some orange ink is used for dotted decoration.

The classical tradition was slow to use capital letters for initials at all. In Roman texts, it's often hard to even separate words. By this time, capital letters were common in Italy, but they were often placed in the left margin, almost cut off from the text. The Insular style, where decoration reaches into the text and takes over more and more of it, was a big new idea. The Bobbio Jerome, which dates to before 622 AD, from Bobbio Abbey (an Irish mission center in northern Italy), has a more detailed initial with color. It shows even more developed Insular features, even in such a faraway place. From the same workshop and around the same time, the Bobbio Orosius has the earliest carpet page, though it's quite simple.

Durham Gospel Book Fragment This is the earliest painted Insular book that survives. It was made in Lindisfarne around 650 AD. Only seven pages of the book remain, and not all have decorations. This book introduces interlace patterns and uses Celtic designs from metalwork. Two of the surviving pages were designed to be seen together.

Book of Durrow This is the earliest surviving Gospel Book with a full set of decorations, though some are missing. It has six carpet pages, a full-page picture of the four evangelists' symbols, four full-page pictures of the evangelists' symbols, four pages with very large first letters, and decorated text on other pages. Many smaller groups of letters are also decorated. Its date and origin are still debated. People usually suggest 650–690 AD and Durrow in Ireland, Iona, or Lindisfarne. The influences on the decoration are also very debated, especially about whether it was influenced by Coptic or other Middle Eastern art.

After large first letters, the next letters on the same line, or for a few lines after, continue to be decorated but at a smaller size. Dots around the outside of large first letters are used a lot. The figures are very stylized. Some pages use Germanic interlaced animal patterns, while others use all the Celtic geometric spirals. Each page uses a different and consistent set of decorative patterns. Only four colors are used, but you hardly notice any limit from this. All the elements of Insular book style are already in place. The work, though high quality, is not as refined as in the best later books, nor is the detail as small.

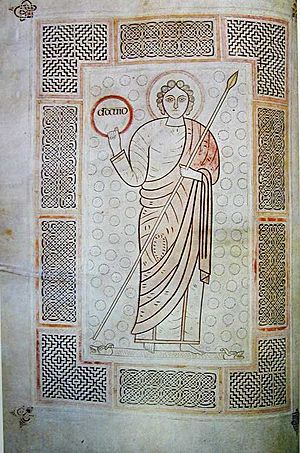

Lindisfarne Gospels This Gospel Book was made in Lindisfarne by Eadfrith, Bishop of Lindisfarne, between about 690 AD and his death in 721 AD. It's in the style of the Book of Durrow, but even more detailed and complex. All the letters on the pages starting the Gospels are highly decorated in one design. Many two-page spreads are designed as a single unit, with carpet pages facing an incipit ("Here begins..") initial page at the start of each Gospel. Eadfrith was almost certainly the scribe (writer) and the artist. There are four Evangelist portraits, clearly from the classical style but without any sense of depth. The borders around them are much simpler than the text page decorations. There are clearly two styles that Eadfrith doesn't try to fully combine. The carpet-pages are incredibly complex and beautifully made.

Lichfield Gospels This fancy Gospel book was likely made in Lichfield around 730 AD. It has eight major decorated pages, including a stunning cross-carpet page and pictures of the evangelists Mark and Luke. The gospels of Matthew and Mark and the beginning of Luke survive. From its time in Wales, pages include notes in the margins that are some of the earliest examples of Old Welsh writing. The book has been at Lichfield Cathedral since the late 900s, except for a short time during the English Civil War.

St Petersburg Bede This book is thought to have been made at Monkwearmouth-Jarrow Abbey in Northumbria between about 730–746 AD. It has larger opening letters where metalwork styles of decoration can be clearly seen. There are thin bands of interlace within the parts of letters. It also has the earliest historiated initial (a decorated first letter with a picture inside), a bust likely of Pope Gregory I. This, like some other decorations, clearly comes from a Mediterranean design. Color is used, but in a simple way.

Book of Kells This book is usually dated to around 800 AD, though sometimes earlier. Its origin is debated between Iona and Kells, or other places. It's often thought to have been started in Iona and then continued in Ireland after Viking raids. The book is almost complete, but the decoration is not finished; some parts are just outlines. It is far more decorated than any previous book in any style. Every page (except two) has many small decorated letters. Although there is only one carpet page, the incipit initials are so densely decorated, with only a few letters on the page, that they take over this function. Human figures are more common than before, though they are very stylized and closely surrounded by decoration, as crowded as on the initial pages. A few scenes like the Temptation and Arrest of Christ are included, as well as a Madonna and Child surrounded by angels (the earliest Madonna in a Western book). More pictures might have been planned or made and then lost. Colors are very bright, and the decoration has great energy, with spiral shapes being most common. Gold and silver are not used.

Other Insular Books

A special type of Insular book is the pocket gospel book. These are much less decorated, but several have Evangelist portraits and other designs. Examples include the Book of Mulling, Book of Deer, Book of Dimma, and the smallest of all, the Stonyhurst Gospel (now in the British Library). This is a 600s Anglo-Saxon text of the Gospel of John that belonged to St Cuthbert and was buried with him. Its beautifully crafted goatskin cover is the oldest Western bookbinding that survives. It's a very rare example of Insular leatherwork, in excellent condition.

Both Anglo-Saxon and Irish books have a rougher finish to their vellum (treated animal skin for writing), compared to the smooth vellum of books from mainland Europe at the time. It seems that, unlike later periods, the scribes who copied the text were often also the artists who made the decorations. They might even have been the most important people in their monastery.

Insular Art's Influence on Anglo-Saxon Art

In England, the influence of European styles began very early. The Gregorian mission from Rome brought the St Augustine Gospels and other books that are now lost. Other books were imported from Europe early on. The 700s Cotton Bede shows mixed elements in its decoration. So does the Stockholm Codex Aureus from a similar time, probably written in Canterbury. In the Vespasian Psalter, it's clear which style is becoming more important. All these books were written south of the river Humber. But the Codex Amiatinus, from before 716 AD from Jarrow, is written in a fine uncial script. Its only picture is in an Italian style, with no Insular decoration. It has been suggested this was only because the book was made to be given to the Pope. The dating is partly known from the land given to raise the cattle needed to make the vellum for three complete, but unillustrated, Bibles. This shows the resources needed to make the large books of that time.

Many Anglo-Saxon books written in the south, and later the north, of England show strong Insular influences until the 900s or later. But the main style comes from mainland Europe. Carpet-pages are not found, but many large pictures of people are. Panels of interlace and other Insular patterns continue to be used as one part of borders and frames that are ultimately from classical design. Many European books, especially in areas influenced by the Celtic missions, also show such features well into the early Romanesque period. "Franco-Saxon" is a term for a style of book decoration in north-eastern France that used Insular-style decoration. This included very large first letters, sometimes with pictures inside, mixed with pictures typical of French styles. This style continued until as late as the 1000s.

Insular Sculpture

Large stone high crosses, usually put up outside monasteries or churches, first appeared in the 700s in Ireland. Perhaps the earliest was at Carndonagh, Donegal, a monastery with links to Iona. These seem to be later than the earliest Anglo-Saxon crosses, which might be from the 600s.

Later Insular carvings found across Britain and Ireland were almost entirely geometric. This was also true for the decoration on the earliest crosses. By the 800s, figures were carved. The largest crosses have many figures in scenes on all surfaces. These often show scenes from the Old Testament on the east side and the New Testament on the west, with a Crucifixion (Jesus on the cross) at the center. The 900s Muiredach's High Cross at Monasterboice is usually seen as the best of the Irish crosses. In later examples, the figures become fewer and larger, and their style starts to blend with the Romanesque style, like at the Dysert Cross in Ireland.

The 700s Northumbrian Ruthwell Cross is the most impressive remaining Anglo-Saxon cross. Sadly, it was damaged by Presbyterian iconoclasm (destruction of images). Like most Anglo-Saxon crosses, the original cross head is missing. Many Anglo-Saxon crosses were much smaller and thinner than the Irish ones. So, they only had room for carved plants. But the Bewcastle Cross, Easby Cross, and Sandbach Crosses are other surviving crosses with large areas of carved figures. These figures are larger than any early Irish examples. Even early Anglo-Saxon examples mix vine-scroll decoration from Europe with interlace panels. In later ones, the vine-scroll becomes the norm, just like in books. Old writings suggest there were many carved stone crosses across England, and also straight stone shafts, often used as grave-markers. But most surviving ones are in the northern counties. There are remains of other large stone sculptures in Anglo-Saxon art, even from earlier times, but nothing similar from Ireland.

Pictish Standing Stones

The stone monuments put up by the Picts of Scotland (north of the Clyde-Forth line) between the 500s and 700s are very striking. They are carved in the typical Easter Ross style, which is related to Insular art, but with much less classical influence. The animal shapes are often very similar to those found in Insular books, where they usually represent the symbols of the Evangelists. This might mean these shapes came from Pictish art, or from another shared source. The carvings are from both pagan and early Christian times. The Pictish symbols, which are still not fully understood, don't seem to have bothered Christians. The purpose and meaning of the stones are only partly known. Some think they were personal memorials, with the symbols showing membership in clans or families. They might also show old ceremonies. Examples include the Eassie Stone and the Hilton of Cadboll Stone. It's possible they had other uses, like marking tribal lands. It has also been suggested that the symbols could have been a kind of picture writing system.

There are also a few examples of similar decoration on Pictish silver jewelry. These include the Norrie's Law Hoard from the 600s or earlier, much of which was melted down when found. Also, the 700s St Ninian's Isle Hoard has many brooches and bowls. The surviving items from both are now in the National Museum of Scotland.

Legacy of Insular Art

The real legacy of Insular art is not just its specific style features. It's how it moved away from the classical way of decorating books and other artworks. The wild energy of Insular decoration, spiraling across formal sections, became a feature of later medieval art, especially Gothic art. This happened even in areas where specific Insular patterns were hardly used, like in architecture. Mixing pictures with ornaments also remained a key part of all later medieval book decoration. In fact, for how complex and dense the mix is, Insular books are only matched by some 1400s Flemish books. It's also clear that these features are always more noticeable in northern Europe than in the south. Italian art, even in the Gothic period, always kept a certain classical clearness in its forms.

You can clearly see Insular influence in Carolingian books. This is true even though these books were also trying to copy the grand styles of Rome and Byzantium. Very large first letters, sometimes with figures inside, were kept. Also, more abstract decoration than found in classical models was used. These features continued in Ottonian and French book decoration and metalwork of the time. Then, the Romanesque period further removed classical limits, especially in books and column capitals. "Franco-Saxon" is a term for a style of late Carolingian book decoration in north-eastern France that used Insular-style decoration. This included very large first letters, sometimes with pictures inside, mixed with pictures typical of French styles. This style continued until as late as the 1000s.

|