Hiberno-Scottish mission facts for kids

The Hiberno-Scottish mission was a big effort by Gaelic missionaries from Ireland in the 500s and 600s. They traveled to places like Scotland, Wales, England, and France. Their goal was to share Celtic Christianity. This type of Christianity first spread in the Kingdom of Dál Riata, which included parts of Ireland and western Scotland. From the 700s and 800s, these early trips were called 'Celtic Christianity'.

There are different ideas about how the Hiberno-Scottish mission related to the Catholic Church. Some say it followed the rules of the Holy See (the Pope). Others say there were disagreements between Celtic and Catholic church leaders. Everyone agrees that the mission was not strictly planned or controlled.

Contents

What Does the Name Mean?

The word Hibernia is the old Latin name for the island of Ireland.

The Latin word Scotti referred to the Gaelic-speaking people from Ireland and western Scotland. From this, another Latin name for their land developed: 'Scotia'.

Schottenklöster is a German word meaning 'Scottish monasteries'. This name was given to the Bible schools set up by Gaelic missionaries in Europe, especially in Germany. Many of these schools later became Benedictine monasteries. Because of this time, Ireland got its nickname, "Island of Saints and Scholars."

Columba's Mission in Scotland

Columba was an Irish prince born in 521. He studied at the Bible school at Clonard. When he was 25, Columba started his first mission. He set up a school in Derry. After that, Columba is said to have started over 300 churches and church schools. Adamnan wrote about Columba:

He could not pass the space even of a single hour without applying himself either to prayer, or reading, or writing, or else to some manual labor.

In 563, Columba sailed to Scotland with about 200 other missionaries. They wanted to share Celtic Christianity with the Picts, who mostly followed older beliefs. The lord of the Mull, a Gael from Dál Riata, was related to Columba. He gave the missionaries the island of Iona. There, they started a Bible school.

Bede wrote that Columba taught the Picts about God. This suggests that teaching the Bible was the main way they spread their faith. Students often studied for 18 years before becoming priests. This shows how much deep religious learning was needed in the Celtic Church. This school stayed Celtic until other monks, the Benedictines, took over in 1204.

Dunod's Mission in Wales

Dunod was a student of Columba. He started a Bible school at Bangor-on-Dee in 560. This school was so large that seven leaders each looked after at least 300 students.

Dunod's mission had some disagreements with Augustine. Pope Gregory I had given Augustine authority over all the bishops in Britain when he arrived in 597. Neander wrote about a meeting:

The abbot of the most distinguished British monastery, at Bangor, Deynoch by name, whose opinion in ecclesiastical affairs had the most weight with his countrymen, when urged by Augustin to submit in all things to the ordinances of the Roman Church, gave him the following remarkable answer: “We are all ready to listen to the church of God, to the pope at Rome, and to every pious Christian, that so we may show to each, according to his station, perfect love, and uphold him by word and deed. We know not, that any other obedience can be required of us towards him whom you call the pope or the father of fathers.”

Representatives from Bangor met with Augustine twice. They said they could not change their old customs without their people's agreement. They also said they could not accept the Pope's leadership or Augustine as their archbishop. Dunod said they followed what their holy fathers had taught them, who were friends of God and followers of the apostles.

In Wales, Celtic Christianity kept its unique ideas for a long time. However, the Bible school at Bangor was destroyed in 613 by King Æthelfrith.

Aidan's Mission in England

Aidan studied at Iona. In 634, King Oswald invited Aidan to his court in Northumbria. He wanted Aidan to teach the ideas of Celtic Christianity. Oswald gave Aidan the island of Lindisfarne to set up a Bible school.

When Aidan died in 651, Finan took over, and then Colman. Both of them had also studied at Iona. From Northumbria, Aidan's mission spread to other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. Similar Bible schools were started in places like Bernicia, Deira, Mercia, and East Anglia. It is thought that about two-thirds of the Anglo-Saxon people became Celtic Christians during this time.

Columbanus's Mission in Francia

Columbanus was born in 543. He studied at Bangor Abbey until around 590. Then, he traveled to Europe with twelve friends, including Attala, Gallus, and Domgal.

King Guntram of Burgundy welcomed the mission. Schools were started at Anegray, Luxeuil, and Fontaines. When Theuderic II forced Columbanus to leave Burgundy in 610, Columbanus started Mehrerau Abbey at Bregenz. He had help from Theudebert II. When Theuderic II took over Austrasia in 612, Columbanus went to Lombardy. There, King Agilulf welcomed him. In 614, he started a school at Bobbio.

During the 600s, Columbanus's students and other Gaelic missionaries founded many monasteries. These were in places that are now France, Germany, Belgium, and Switzerland. Some of the most famous are: St. Gall in Switzerland, Disibodenberg in the Rhine area, Bèze, and Remiremont Abbey.

In Italy, places like Fiesole produced important figures like Saint Donatus of Fiesole. Another early Schottenkloster was Säckingen in Baden. It was founded by the Irish missionary Fridolin of Säckingen. Other Hiberno-Scottish missionaries active then included Wendelin of Trier, Saint Kilian, Saint Gall (who founded the Abbey of St. Gall), and Rupert of Salzburg.

After Columbanus (700s to 1200s)

Irish-Scottish work in Europe continued after Columbanus died. Monasteries were also founded in Anglo-Saxon England. One of the first was around 630 at "Cnobheresburgh" in East Anglia. Other places like Malmesbury Abbey and Glastonbury Abbey had strong Irish connections.

The importance of Iona decreased. From 698 until the time of Charlemagne in the 770s, the Irish-Scottish efforts in the Frankish Empire were continued by the Anglo-Saxon mission.

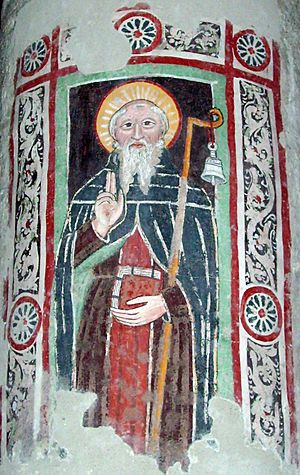

Irish monks called Papar are believed to have been in Iceland before the Norse settled there from 874 AD. The oldest book mentioning the Papar is the Íslendingabók ("Book of the Icelanders"), written between 1122 and 1133. It says the Norse found Irish priests with bells and staffs in Iceland when they arrived. These figures are also mentioned in the Icelandic Landnámabók ("Book of Settlements").

Among the Irish monks in Central Europe, two very important thinkers were Marianus Scotus and Johannes Scotus Eriugena. Stories about Irish foundations are in a German text called Charlemagne and the Scottish [Irish] Saints.

The rules of St. Columbanus were first followed in most of these monasteries. But soon, the rules of St. Benedict became more common. Later Gaelic missionaries founded new monasteries. These included Honau in Baden (around 721) and Murbach in Upper Alsace (around 727). Other Gaelic monks also helped restore older monasteries.

Towards the end of the 1000s and in the 1100s, many Schottenklöster were built in Germany just for Irish monks. Around 1072, three monks, Marianus, Iohannus, and Candidus, settled at a small church in Regensburg. More monks joined them, and a larger monastery was built around 1090. This became the famous Scots Monastery of St. James in Regensburg. It was the main house for many other Schottenklöster.

This monastery founded others like St. James at Würzburg (around 1134), St. Aegidius at Nuremberg (1140), and Our Blessed Lady at Vienna (1158). These, along with the Abbey of St. James at Erfurt (1036), formed a famous group of German Schottenklöster. This group was officially recognized by Pope Innocent III in 1215.

Later Years (1300s Onwards)

In the 1300s and 1400s, most of these monasteries started to decline. This was partly because there were not enough Irish monks. Also, there were problems with discipline and money.

Because of this, the monasteries of Nuremberg and Vienna were no longer part of the Irish group in 1418. German monks took them over. St. James's Abbey, Würzburg, was left without any monks after 1497. It was then filled with German monks. The abbey of Constance also declined and was closed in 1530. The one in Memmingen disappeared during the Protestant Reformation.

The Abbey of Holy Cross at Eichstatt seems to have closed early in the 1300s. Due to the Protestant Reformation in Scotland, many Scottish Benedictine monks left their country. They found safety in the Schottenklöster in Germany during the 1500s.

The Scottish monasteries in Regensburg, Erfurt, and Würzburg became strong again for a while. But efforts to get back the monasteries of Nuremberg, Vienna, and Constance for Scottish monks failed.

In 1692, Abbot Placidus Flemming of Regensburg reorganized the Scottish group. It now included only the monasteries of Regensburg, Erfurt, and Würzburg. These were the only Schottenklöster left in Germany. He also started a seminary (a school for priests) connected to the Regensburg monastery.

However, in 1803, monasteries were forced to become secular (not controlled by the church). This ended the Scottish abbeys of Erfurt and Würzburg. Only St. James's at Regensburg remained. After 1827, this monastery was allowed to accept new monks again. But the number of monks slowly dropped.

With no hope of growth, Pope Pius IX closed this last Schottenkloster on September 2, 1862. Its money was given to the local seminary in Regensburg and the Scots College in Rome.

See also

- Gaelic Ireland

- Anglo-Saxon mission

- Culdee

- Schottenstift, Vienna

- Pirmin

- Quartodecimanism

- Christianisation of Anglo-Saxon England

- Gregorian mission

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |