Kingdom of the Lombards facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Kingdom of the Lombards

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 568–774 | |||||||||||||||||||

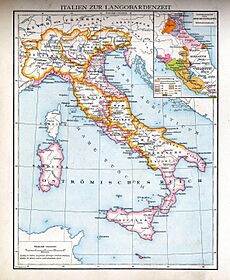

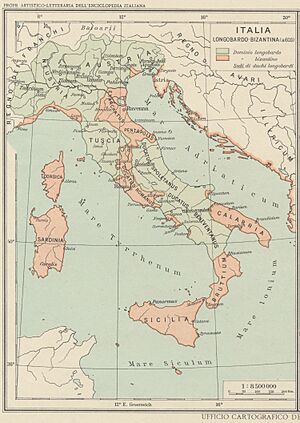

The Lombard Kingdom in 740, under King Liutprand.

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Pavia | ||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Vulgar Latin Lombardic |

||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Christianity

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Feudal elective monarchy | ||||||||||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||||||||||

|

• 565–572

|

Alboin (first) | ||||||||||||||||||

|

• 756–774

|

Desiderius (last) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||||||||||||

|

• Lombard migration

|

568 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

• Frankish invasion

|

774 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Tremissis | ||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

The Kingdom of the Lombards was an important state in the Early Middle Ages. It was created by the Lombards, a Germanic people, in Italy during the late 500s. The king was usually chosen by the most powerful nobles, called dukes. The kingdom was divided into many smaller areas, also called duchies, which were run by these dukes. Each duchy was then split into even smaller areas called gastaldates. The main city and capital of the kingdom was Pavia, located in what is now northern Italy.

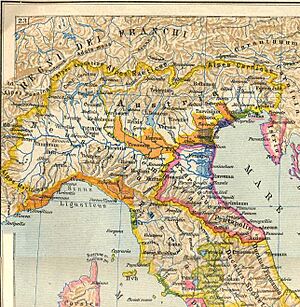

The Byzantine Empire ruled parts of Italy and didn't like the Lombard invasion. For a long time, the Byzantines controlled areas like the Exarchate of Ravenna and the Duchy of Rome. These areas separated the northern Lombard duchies (called Langobardia Maior) from the two large southern duchies of Spoleto and Benevento (called Langobardia Minor). Because of this split, the southern duchies were much more independent.

Over time, the Lombards started to adopt Roman customs, names, and traditions. By the late 700s, their original language, clothes, and hairstyles had mostly disappeared. At first, many Lombards were either Arian Christians (a different type of Christianity) or followed pagan beliefs. This caused problems with the Roman people, the Byzantine Empire, and the Pope. However, by the end of the 600s, most Lombards had become Catholic. Despite this, their conflicts with the Pope continued. This led to their power weakening, and eventually, the Franks conquered their kingdom in 774. Charlemagne, the Frankish king, took the title "King of the Lombards." However, he never fully controlled Benevento, the southernmost Lombard duchy. The Kingdom of the Lombards was one of the last smaller Germanic kingdoms in Europe to fall.

Some parts of Italy, like Latium, Sardinia, Sicily, Calabria, Naples, Venice, and southern Apulia, were never ruled by the Lombards. A smaller "Kingdom of Italy," which was a legacy of the Lombards, continued to exist for many centuries as part of the Holy Roman Empire. The famous Iron Crown of Lombardy, a very old royal crown, might have come from Lombard Italy in the 600s. It was used to crown kings of Italy until Napoleon Bonaparte in the early 1800s.

Contents

How the Kingdom Was Run

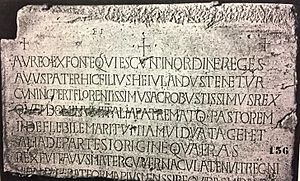

The earliest Lombard law book, the Edictum Rothari, mentions the use of seal rings. These rings became very important for official royal business during the rule of King Ratchis. For example, the king required them to be used on passports. There is also some evidence that dukes used seal rings in the Duchy of Benevento. The use of these seals shows that the Lombards kept some of the old Roman ways of government.

History of the Lombards

The 500s: Kingdom Begins

Starting the Kingdom

In the 500s, the Byzantine Emperor Justinian tried to take back control of lands that used to be part of the Western Roman Empire. This led to the Gothic War (535–554) against the Ostrogothic Kingdom. This war was long and very destructive. It caused many people to move and destroyed a lot of property. Things got even worse because of a very cold period in 536, which led to widespread famine (538–542). Then, a terrible plague (541–542) hit, killing many people.

Even though the Byzantine Empire won the war, it was a very costly victory. Italy's population dropped sharply, and the land became poor and empty.

After the war, the Lombards, a Germanic group who had been allies of the Byzantines, began a large migration. In the spring of 568, the Lombards, led by King Alboin, moved from an area called Pannonia. They quickly defeated the small Byzantine army guarding Italy.

The arrival of the Lombards broke Italy's political unity for the first time in centuries. The peninsula was now split between Lombard and Byzantine territories, and these borders often changed.

The Lombards settled in two main areas in Italy. Langobardia Maior was in northern Italy, with the capital at Ticinum (modern-day Pavia). Langobardia Minor included the Lombard duchies of Spoleto and Benevento in southern Italy. The areas still under Byzantine control were called "Romania" (now the Italian region of Romagna) in northeastern Italy. Their main stronghold was the Exarchate of Ravenna.

When they arrived in Italy, King Alboin gave control of the Eastern Alps to his trusted leader, Gisulf. Gisulf became the first Duke of Friuli in 568. This duchy, based in Cividale del Friuli, often fought with Slavic people nearby. Because of its constant military needs, the Duchy of Friuli had more independence than other northern duchies until the rule of Liutprand (712–744).

Over time, more Lombard duchies were created in important cities. This was mainly for military reasons, as dukes were army commanders. They were in charge of securing land and defending it from attacks. However, having many duchies also led to political problems and made the Lombard kings less powerful.

In 572, after Pavia became the royal capital, King Alboin was killed. His wife, Rosamund, and her lover, Helmichis, planned the murder. They tried to take power, but most Lombard dukes didn't support them. Helmichis and Rosamund had to flee to Byzantine territory.

Cleph and the Dukes' Rule

Later in 572, the dukes chose Cleph as the new king. Cleph expanded the kingdom's borders, conquering Tuscia and attacking Ravenna. He tried to break down the old Roman and Ostrogothic ways of running the government. He did this by taking land and wealth from many Roman nobles. But in 574, Cleph was also killed by someone in his own group, possibly working with the Byzantines.

After Cleph's death, no new king was chosen for ten years. During this time, the dukes ruled their duchies like independent kings. At this point, the dukes were simply the leaders of different Lombard families (called fara). They acted on their own, partly because their warriors wanted to raid and get loot. This unstable situation caused the old Roman-Italian government system to collapse.

The Lombards became the new ruling class in Italy. They made the Roman people who worked the land give them one-third of their crops. This money went to the Lombard families, who managed it in special buildings called halls. The old economic system, based on large farms worked by peasants, didn't change much, but the new rulers now benefited from it.

New Stability: Autari, Agilulf, and Theudelinda

After ten years without a king, everyone realized they needed a strong central government. The Franks and Byzantines were putting pressure on them, and the Lombards couldn't afford such a weak system. In 584, the dukes agreed to crown Cleph's son, Autari. They gave the new king half of their own property.

Autari then began to reorganize the Lombards and make their settlements in Italy more stable. He took the title Flavio, which was used by Ostrogoth kings. By doing this, he showed he was also the protector of all Romans in Lombard territory. This was a clear message against the Byzantines, claiming the legacy of the Western Roman Empire.

Militarily, Autari defeated both the Byzantines and the Franks. In 585, he pushed the Franks out of what is now Piedmont. He also made the Byzantines ask for a truce for the first time since the Lombards arrived. Finally, he captured the last Byzantine stronghold in northern Italy, Isola Comacina in Lake Como.

To make peace with the Franks, Autari tried to marry a Frankish princess, but it didn't work out. So, the king turned to the Franks' traditional enemies, the Bavarii. He married Theodelinda, a princess from the important Lethings family. This marriage helped the Lombard monarchy connect itself to the legendary King Wacho, who ruled from 510 to 540.

The alliance with the Bavarii led to the Franks and Byzantines becoming closer. But Autari managed to fight off Frankish attacks in 588 and again in the 590s. According to the historian Paul the Deacon, Autari's time as king brought the first real stability to the Lombard kingdom. Paul wrote that there was "no violence, no plots; no one oppressed anyone unjustly, no one robbed; there were no thefts, no robberies; everyone went where they wanted, safely and without fear."

Autari died in 590, likely from poisoning. According to legend, his young widow Theodelinda chose the next king and her new husband: Agilulf, the Duke of Turin. The next year (591), Agilulf was officially approved by the Assembly of the Lombards in Milan. Queen Theodelinda had a big influence on Agilulf's decisions.

After a rebellion by some dukes was stopped in 594, Agilulf and Theodelinda worked to strengthen their control over Italy. They also secured their borders by making peace treaties with France and the Avars. The truce with the Byzantines was often broken, and the Lombards made significant gains until 603. In northern Italy, Agilulf captured cities like Parma, Piacenza, Padova, Cremona, and Mantua. In the south, the duchies of Spoleto and Benevento also expanded Lombard lands.

Istria was attacked by the Lombards many times. Even when Istria was part of the Exarchate of Ravenna, a Lombard named Gulfaris became powerful there, calling himself dux Istriae (Duke of Istria).

The strengthening of royal power, started by Autari and continued by Agilulf, also meant a new way of organizing the kingdom. It was divided into stable duchies. Each duchy was led by a duke, who was not just a family head but also a royal official with public authority. Duchies were set up in important places, helping many cities grow along the main trade routes. Besides the dukes, there were smaller officials called sculdahis and gastalds.

This new way of organizing power, which was less about family groups and more about managing land, was a big step in making the Lombard kingdom stronger in Italy. It slowly changed from just a military occupation to a more proper state. Including the Romans (the defeated people) was necessary. Agilulf made some symbolic choices to strengthen his power and gain the trust of the Latin people. For example, his son Adaloald's ascension to the throne in 604 followed a Byzantine ceremony. He chose to use the old Roman city of Milan as his capital instead of Pavia, with Monza as a summer home. On a special crown, he called himself Gratia Dei rex totius Italiae ("By the grace of God king of all Italy"), not just "King of the Lombards."

These efforts also included strong pressure, especially from Theodelinda, to convert the Lombards to Catholicism. Many Lombards were still pagan or Arian at this time. The rulers also tried to heal the Three Chapter schism (a split where the Patriarch of Aquileia had broken ties with Rome). They kept in touch with Pope Gregory the Great and encouraged the building of monasteries, like the one founded by Saint Columbanus in Bobbio.

Art also thrived under Agilulf and Theodelinda. Theodelinda founded the Basilica of St. John (Duomo of Monza) and the Royal Palace of Monza. Beautiful gold items were created, such as the Agilulf Cross, the Hen with seven chicks, the Theodelinda Gospels, and the famous Iron Crown. All these treasures are kept in the Duomo of Monza treasury.

The 600s: Religious and Political Changes

Arian Revival: Arioald and Rothari

After Agilulf died in 616, his young son Adaloald became king. His mother, Theodelinda, acted as regent (ruler until the king was old enough). She continued Agilulf's pro-Catholic policies and kept peace with the Byzantines. This made many Lombard warriors and Arians very unhappy. A civil war began in 624, led by Arioald, the Duke of Turin and Adaloald's brother-in-law. Adaloald was removed from power in 625, and Arioald became king.

This change in power against Adaloald and Theodelinda's family increased the rivalry between Arian and Catholic groups. This conflict also had political meaning. The Arians were against peace with Byzantium and the Pope. They wanted a more aggressive policy of expansion.

Arioald (ruled 626–636) moved the capital back to Pavia. He faced many internal conflicts and outside threats. He managed to stop an attack by the Avars in Friuli, but he couldn't stop the Franks from gaining more influence in the kingdom. When he died, legend says that Queen Gundeperga, his wife, got to choose her new husband and king, just like her mother Theodelinda. She chose Rothari, the Duke of Brescia, who was an Arian.

Rothari ruled from 636 to 652. He led many military campaigns and brought almost all of northern Italy under Lombard rule. He conquered Liguria (643), including Genoa, Luni, and Oderzo. Even though he completely defeated the Byzantine Exarch of Ravenna, killing him and his army, he couldn't force the Exarchate to fully submit to the Lombards. Inside the kingdom, Rothari made the central government stronger, especially in Langobardia Maior. In the south, the Duke of Benevento, Arechi I, who was also expanding Lombard lands, accepted the King of Pavia's authority.

Rothari is best known for his famous edict, issued in 643 in Pavia. This edict was written in Latin and approved by an assembly of the army (a gairethinx). The Edict collected and organized Germanic laws and customs. But it also added important new rules, showing how much Latin influence was growing among the Lombards. The edict tried to stop the practice of feud (private revenge) by increasing the weregild (money paid as compensation) for injuries or murders. It also limited the use of the death penalty.

Bavarian Family Returns

After Rothari's son Rodoald ruled for a short time (652-653), the dukes chose Aripert I, the Duke of Asti and grandson of Theodolinda, as the new king. This brought the Bavarian family back to the throne. The Catholic Aripert quickly put an end to Arianism. When Aripert died in 661, his will divided the kingdom between his two sons, Perctarit and Godepert. This was a unique way of succession for the Lombards. A conflict broke out between Perctarit, who was in Milan, and Godepert, who stayed in Pavia. The Duke of Benevento, Grimoald, came with a large army to support Godepert. But when he arrived in Pavia, he killed Godepert and took his place. Perctarit, now in danger, fled to the Avars.

Grimoald was accepted by the Lombard nobles, but he still had to deal with the group who supported the rightful king. They tried to get international allies to bring Perctarit back. Grimoald, however, convinced the Avars to send Perctarit back. When Perctarit returned to Italy, he had to show loyalty to Grimoald before escaping to the Franks of Neustria. These Franks attacked Grimoald in 663. Grimoald, who was disliked by Neustria because he was allied with the Franks of Austrasia, defeated them at Refrancore, near Asti.

Grimoald also defeated an attempt by the Byzantine Emperor Constans II to retake Italy in 663. Grimoald ruled with more power than any king before him. He gave the Duchy of Benevento to his son Romuald. He also made sure the duchies of Spoleto and Friuli were loyal by choosing their dukes. He encouraged different groups in the kingdom to get along. He was seen as a wise lawgiver, adding new laws to the Edict, a patron (building a church in Pavia), and a brave warrior.

When Grimoald died in 671, his young son Garibald became king. But Perctarit returned from exile and quickly removed him. Perctarit immediately made a deal with Grimoald's other son, Romualdo I of Benevento. Romualdo promised loyalty, and in return, his duchy would remain independent. Perctarit followed his family's traditions, supporting the Catholic Church against Arianism. He sought and achieved peace with the Byzantines, who recognized Lombard rule over most of Italy. He also put down a rebellion by the Duke of Trent, Alahis, though he had to give Alahis some land.

Alahis rebelled again later, joining with those who opposed the pro-Catholic policies of Perctarit's family. When Perctarit died in 688, his son and successor Cunipert was at first defeated and forced to hide on the Isola Comacina. Only in 689 did he manage to stop the rebellion, defeating and killing Alahis in the Battle of Coronate at the Adda River.

This crisis showed the differences between the two regions of Langobardia Maior. Neustria, in the west, was loyal to the Bavarian rulers. They were pro-Catholic and wanted peace with Rome and Byzantium. On the other hand, Austria, in the east, followed traditional Lombard paganism and Arianism. They favored a more warlike approach.

The dukes of Austria were against the growing "Latinization" of customs, court practices, law, and religion. They believed this was making the Lombards lose their Germanic identity. Cunipert's victory allowed him to continue bringing peace to the kingdom, always with a pro-Catholic focus. A church meeting (a synod) held in Pavia in 698 confirmed that the three chapters (a theological dispute) were now part of Catholicism.

The 700s: Peak and Fall

A Time of Trouble

Cunipert's death in 700 started a period of trouble over who would be king. Cunipert's young son, Liutpert, was supposed to take the throne. But the Duke of Turin, Raginpert, a powerful member of the Bavarian family, immediately challenged him. Raginpert defeated Liutpert's supporters in Novara and became king in early 701. However, he died after only eight months, leaving the throne to his son Aripert II.

Liutpert's supporters reacted quickly. They imprisoned Aripert and put Liutpert back on the throne. But Aripert managed to escape and fight his rivals. In 702, he defeated them in Pavia, imprisoned Liutpert, and took the throne. Soon after, he finally defeated all opposition. Only one of Liutpert's supporters, Ansprand, managed to escape to Bavaria. Aripert then crushed another rebellion and followed a strong pro-Catholic policy.

In 712, Ansprand returned to Italy with an army from Bavaria and fought Aripert. The battle was uncertain, but the king acted cowardly, and his supporters abandoned him. He died trying to escape to the Frankish kingdom, drowning in the Ticino River because of the weight of the gold he was carrying. With his death, the Bavarian family's role in the Lombard kingdom ended.

Liutprand: The Kingdom's Golden Age

Ansprand died after only three months as king, leaving the throne to his son Liutprand. His reign was the longest of all Lombard kings. People admired him greatly for his bravery, courage, and political skill. Thanks to these qualities, Liutprand survived two attempts on his life. He also showed great skill in the many wars he fought during his long reign.

Liutprand was a strong leader. He was of Germanic descent and ruled a nation that was now mostly Catholic. He was also seen as a "loving king," even though he tried many times to take control of Rome. He successfully fought Saracen pirates in Sardinia and Arles (where his ally Charles Martel had called him). This increased his reputation as a Christian king.

His alliances with the Franks (he even symbolically adopted the young Pepin the Short) and with the Avars on the eastern borders allowed him to focus on Italy. But he soon clashed with the Byzantines and the Papacy. An early attempt to take advantage of an Arab attack on Constantinople in 717 didn't achieve much. Closer ties with the Pope came later, when tensions grew because of Byzantine taxes and an expedition by the Exarch of Ravenna against Pope Gregory II in 724.

Later, Liutprand used the disagreements between the Pope and Constantinople over iconoclasm (the banning of religious images by Emperor Leo III the Isaurian in 726). He took control of many cities in the Exarchate and the Pentapolis, presenting himself as the protector of Catholics. To avoid upsetting the Pope, he gave up occupying the town of Sutri. However, Liutprand gave the city not to the emperor, but to "the apostles Peter and Paul." This gift, known as the Donation of Sutri, became the legal basis for the Pope to have temporal power (ruling land), which eventually led to the Papal States.

In the following years, Liutprand allied with the Exarch against the Pope, but also with the Pope against the Exarch. He then launched an attack that brought the duchies of Spoleto and Benevento under his control. He eventually helped negotiate peace between the Pope and the Exarch, which benefited the Lombards. No Lombard king had ever achieved such results in wars with other powers in Italy. In 732, his nephew Hildeprand, who would succeed him, briefly took Ravenna. But the Venetians, allied with the new pope, Gregory III, drove him out.

Liutprand was the last Lombard king to rule a truly unified kingdom. Later kings would face strong internal opposition, which eventually led to the kingdom's downfall. His power came not only from his personal qualities but also from how he reorganized the kingdom. He strengthened the royal administration in Pavia and clearly defined the legal and administrative roles of the sculdasci, gastalds, and dukes. He was also very active in making new laws. His twelve volumes of laws introduced reforms based on Roman law, improved the court system, changed the wergild, and, most importantly, protected weaker people in society, like children, women, debtors, and slaves.

The kingdom's society and economy had been changing since the 600s. Population growth led to smaller landholdings, which meant more Lombards became poor. This is shown by laws aimed at helping them. On the other hand, some Romans started to become wealthy through trade, crafts, professions, or buying land that Lombards couldn't manage well. Liutprand also helped this process by changing the kingdom's administration and freeing the poorest Lombards from military duties.

The Last Kings

Hildeprand's reign lasted only a few months before Duke Ratchis overthrew him. The details are unclear, as the historian Paul the Deacon's account ends with Liutprand's death. Hildeprand had been made king in 737 when Liutprand was very ill. Liutprand didn't like this choice, but he accepted it once he recovered. So, the new king initially had the support of most nobles. Ratchis, the Duke of Friuli, came from a family that often rebelled against the monarchy. However, he owed his life and title to Liutprand, who had forgiven him after his father was involved in a plot.

Ratchis was a weak ruler. He had to give more freedom to the other dukes. He also had to be careful not to anger the Franks, especially Pepin the Short, who was the powerful de facto (actual) ruler of the Franks and Liutprand's adopted son. Since he couldn't rely on the usual supporters of the Lombard monarchy, he sought help from the gasindii (nobles loyal to the king) and, most importantly, from the Romans.

Ratchis started adopting old Roman customs. He married a Roman woman, Tassia, in a Roman ceremony. He also used the title princeps (prince) instead of the traditional rex Langobardorum (King of the Lombards). These actions made the Lombard people unhappy. They forced him to change his policy, and he suddenly attacked cities in the Pentapolis. However, the Pope convinced him to stop the siege of Perugia. After this failure, Ratchis lost his prestige. The dukes then chose his brother Aistulf as the new king. Aistulf had already replaced Ratchis as duke in Cividale. After a short struggle, Aistulf forced Ratchis to flee to Rome and become a monk at Monte Cassino.

Aistulf's Rule

Aistulf represented the more aggressive dukes who didn't want the Roman population to have an active role. For his expansionist plans, he had to reorganize the army. He included all ethnic groups in the kingdom, though in a lower position as light infantry. All free men, both Roman and Lombard, had to serve in the military. The military rules made by Aistulf often mention merchants, showing that this class had become important.

At first, Aistulf had great success, conquering Ravenna in 751. The king lived in the Palace of the Exarch there and minted coins in the Byzantine style. He wanted to bring all Romans who were under the emperor's rule under Lombard power. The Exarchate was not turned into a duchy but kept its special status as the "seat of the empire." By doing this, Aistulf presented himself as the heir to both the Byzantine Emperor and the Exarch in the eyes of the Italian Romans.

His campaigns brought almost all of Italy under Lombard rule. From 750 to 751, he occupied Istria, Ferrara, Comacchio, and all territories south of Ravenna up to Perugia. By occupying the stronghold of Ceccano, he put more pressure on the lands controlled by Pope Stephen II. In Langobardia Minor, he was able to control Spoleto and, indirectly, Benevento.

Just when it seemed Aistulf could defeat all opposition in Italy, Pepin the Short, the old enemy of Liutprand's family, finally overthrew the Merovingian family in Gaul. He removed Childeric III and became the true king. The Pope's support for Pepin was crucial. Although Aistulf also tried to negotiate with the Pope, these talks failed. Aistulf even tried to weaken Pepin by turning his brother Carloman against him.

Because of the threat Aistulf posed to the new Frankish king, Pepin and Stephen II made an agreement. In exchange for Pepin being formally crowned king, the Franks would come to Italy. In 754, the Lombard army, defending the Locks in Val di Susa, was defeated by the Franks. Aistulf, trapped in Pavia, had to agree to a treaty. He had to give up hostages and land. But two years later, he started another war against the Pope, who again called on the Franks.

Defeated once more, Aistulf had to accept much harsher terms. Ravenna was given not to the Byzantines, but to the Pope, increasing the Pope's land. Aistulf had to accept a kind of Frankish control, lost the continuous territory of his lands, and had to pay a lot of money. The duchies of Spoleto and Benevento quickly allied with the Franks. Aistulf died in 756, soon after this great humiliation.

Aistulf's brother Ratchis left the monastery and tried to become king again, with some initial success. He was opposed by Desiderius, who Aistulf had put in charge of the Duchy of Tuscia and was based in Lucca. Desiderius was not from the Friuli family, who were disliked by the Pope and the Franks. He managed to get their support. The Lombards surrendered to him to avoid another Frankish invasion, and Ratchis was persuaded by the Pope to return to Monte Cassino.

Desiderius, using clever and quiet politics, slowly regained Lombard control over the territory. He gained favor with the Romans again. He created a network of monasteries run by Lombard nobles (his daughter Anselperga became abbess of San Salvatore in Brescia). He dealt with Pope Stephen II's successor, Pope Paul I. He also recognized the Pope's control over many areas that were actually under his power, like the southern duchies. He also used marriage as a political tool. He married his daughter Liutperga to the Duke of Bavaria, Tassilo (763), who was a long-time enemy of the Franks. After Pepin the Short died, he married his other daughter Desiderata (known as Ermengarde in Alessandro Manzoni's play Adelchi) to the future Charlemagne. This offered Charlemagne support against his brother Carloman.

Even with the changing political power, the 700s were the peak of the kingdom and a time of economic growth. The old society of warriors and subjects had changed into a lively mix of classes, including landowners, artisans, farmers, merchants, and lawyers. This era saw great development, including abbeys, especially Benedictine ones. Money became more important in the economy, leading to the creation of a banking class. After an early period where Lombard coins just copied Byzantine ones, the kings of Pavia started making their own gold and silver coins. The Duchy of Benevento, the most independent duchy, also had its own money.

The Kingdom Falls

In 771, Desiderius managed to convince the new pope, Stephen III, to accept his protection. The death of Carloman left Charlemagne, who was now firmly on the throne after divorcing Desiderius's daughter, free to act. The next year, a new pope, Adrian I, who was against Desiderius, changed the alliances. He demanded that Desiderius give up the land he had never given back, which caused Desiderius to restart the war against the cities of Romagna.

Charlemagne, even though he had just started a campaign against the Saxons, came to help the Pope. He feared the Lombards would capture Rome, which would make him lose prestige. Between 773 and 774, he invaded Italy. Again, the defense of the Locks was not effective, partly because of disagreements among the Lombards. Charlemagne, after facing strong resistance, captured the capital, Pavia.

Adalgis, Desiderius's son, found safety with the Byzantines. Desiderius and his wife were sent away to Gaul (France). Charles then called himself Gratia Dei rex Francorum et Langobardorum ("By the grace of God king of the Franks and the Lombards"). This created a personal union of the two kingdoms. He kept the Leges Langobardorum (Lombard laws) but reorganized the kingdom like the Frankish one, putting counts in place of dukes.

The historian Indro Montanelli wrote: "Thus ended Lombard Italy, and nobody can say whether this was, for our country, a fortune or a misfortune. Alboin and his successors were awkward masters, more awkward than Theodoric, so long as they had been barbarians camped on a conquered territory. But now they were assimilating with Italy and could turn it into a Nation, as the Franks were doing in France. But in France there wasn't the Pope. In Italy, there was."

After the Franks conquered Langobardia Maior, only the Southern Lombard Kingdom was still called Langbarðaland (Land of the Lombards), as seen in old Norse writings.

Lombard Kings

Lombards in Art

Literature

For a long time, the "Dark Ages" were seen in a negative light by historians. This made writers less interested in the Lombard kingdom. Few literary works were set in Italy between the 500s and 700s. Important exceptions include works by Giulio Cesare Croce and Alessandro Manzoni. More recently, the writer Marco Salvador from Friuli has written a series of three fiction books about the Lombard kingdom.

Bertoldo

The character of Bertoldo, a humble and clever farmer from Retorbido, who lived during King Alboin's rule (568-572), inspired many stories told over the centuries. In the 1600s, the scholar Giulio Cesare Croce used these stories for his book Le sottilissime astutie di Bertoldo ("the smart craftiness of Berthold") (1606). In 1608, he added Le piacevoli et ridicolose simplicità di Bertoldino ("The pleasant and ridiculous simplicity of Little Bertold"), about Bertold's son.

In 1620, the abbot Adriano Banchieri, a poet and composer, wrote another story: Novella di Cacasenno, figliuolo del semplice Bertoldino ("News of Cacasenno, son of simple Little Bertold"). Since then, these three works are usually published together as Bertoldo, Bertoldino e Cacasenno.

Adelchi

The play Adelchi by Manzoni is set at the very end of the Lombard kingdom. It tells the story of the last Lombard king, Desiderius, and his children Ermengarde (whose real name was Desiderata) and Adalgis. Ermengarde was the divorced wife of Charlemagne, and Adalgis was the last defender of the Lombard kingdom against the Frankish invasion. Manzoni used the Lombard kingdom as the setting. He shaped the characters to fit his interpretation, showing the Lombards as helping to prepare Italy for national unity and independence. At the same time, he showed the period as a "barbaric" time after the glory of classical Rome.

Movies

Three films were inspired by the stories of Croce and Banchieri and are set in the early period of the Lombard kingdom (though they take many liberties with history):

- Bertoldo, Bertoldino e Cacasenno (1936), directed by Giorgio Simonelli;

- Bertoldo, Bertoldino e Cacasenno (1954), directed by Mario Amendola and Ruggero Maccari;

- Bertoldo, Bertoldino e Cacasenno (1984), directed by Mario Monicelli.

The most famous of these is the 1984 film. It featured famous actors like Ugo Tognazzi (Berthold), Maurizio Nichetti (Little Bertold), Alberto Sordi (Fra Cipolla), and Lello Arena (King Alboin).

See also

- Lombard syllogae

- Longobards in Italy: Places of Power (568-774 A.D.)

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |