Indro Montanelli facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Indro Montanelli

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Indro Alessandro Raffaello Schizogene Montanelli

22 April 1909 Fucecchio, Italy

|

| Died | 22 July 2001 (aged 92) Milan, Italy

|

| Nationality | Italian |

| Other names | Cilindro ("Top Hat") |

| Alma mater | University of Florence |

| Occupation |

|

| Years active | 1930–2001 |

| Known for | Famous journalist, employed by Silvio Berlusconi |

|

Notable work

|

General Della Rovere (1959) |

| Awards | Order of the Lion of Finland, Princess of Asturias Awards, World Press Freedom Heroes |

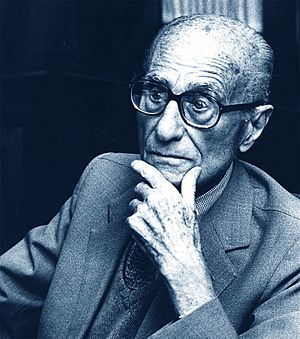

Indro Alessandro Raffaello Schizogene Montanelli OMRI (born April 22, 1909 – died July 22, 2001) was a famous Italian journalist, historian, and writer. He was known for his strong opinions and unique writing style. The International Press Institute recognized him as one of the fifty World Press Freedom Heroes.

Montanelli first supported Benito Mussolini's government and even volunteered for the Second Italo-Ethiopian War. However, he changed his mind in 1943. He then joined a group fighting against the government, called Giustizia e Libertà. In 1944, he was arrested by Nazi soldiers and sentenced to death. Luckily, he managed to escape to Switzerland just before he was to be executed.

After World War II, Montanelli became a well-known conservative writer. In 1977, a terrorist group called the Brigate Rosse (Red Brigades) tried to harm him. He was also a popular author and historian. His most famous work was Storia d'Italia (History of Italy), a huge collection of 22 books. He worked for many years as the editor of il Giornale, a newspaper owned by Silvio Berlusconi. But he disagreed with Berlusconi's political plans and left the newspaper in 1994.

Contents

Biography

Early Life and Education

Indro Montanelli was born in Fucecchio, a town near Florence, Italy. His birthday was April 22, 1909. His father, Sestilio Montanelli, taught philosophy in high school. His mother, Maddalena Doddoli, came from a wealthy family of cotton merchants. His father chose the name "Indro" after the Hindu god Indra.

In 1930, Montanelli earned a law degree from the University of Florence. His final paper was about the election changes made by Benito Mussolini's fascist government. He believed these changes actually ended elections. While studying languages in Grenoble, he realized his true passion was journalism.

Starting His Journalism Career

Montanelli began writing for Il Selvaggio ("The Savage"), a newspaper that supported the fascist movement. In 1932, he also wrote for Universale, a magazine that came out every two weeks and didn't pay its writers. Montanelli later said he first saw fascism as a way to unite Italy. He hoped it would solve problems between the north and south. But his excitement faded in 1935. That's when Mussolini shut down Universale and other papers that questioned fascism.

In 1934, Montanelli started writing for Paris-Soir in Paris. He covered crime stories. Later, he became a foreign reporter in Norway, where he even fished for cod. He then moved to Canada and worked on a farm in Alberta.

From Canada, he began working with Webb Miller at the United Press in New York. Working for United Press taught him to write clearly for everyone. Miller's advice was to "always write as if writing to a milkman from Ohio." Montanelli never forgot this simple, direct style. He often repeated this quote throughout his long career.

One time in the United States, Montanelli was teaching a class. A student didn't understand his essay and told him he was the "imbecille" (idiot). Montanelli, who came from a strict country, realized this was a moment of true democracy. During this time, he also interviewed Henry Ford, the car maker. Ford surprised him by saying he didn't have a driver's license. Montanelli cleverly asked Ford how he felt about changing the world of the Founding Fathers. Ford looked confused, and Montanelli realized that even geniuses don't always see the big impact of their own work.

Reporting from Abyssinia

In 1935, Mussolini's Italy invaded Abyssinia to build an empire. This was called the Second Italo–Abyssinian War. Montanelli stopped working for the United Press and joined the war as a volunteer. He was 23 years old. He later said these were "beautiful two years." He believed Italy was bringing progress to Africa.

Montanelli wrote letters about the war to his father. Without Montanelli knowing, his father sent these letters to Ugo Ojetti, a famous journalist. Ojetti published them regularly in Il Corriere della Sera, Italy's most respected newspaper.

Reporting from the Spanish Civil War

After returning from Abyssinia, Montanelli became a foreign reporter in Spain for Il Messaggero. He covered the Spanish Civil War from the side of Francisco Franco's forces. During this time, he shared a room with Kim Philby. Years later, Philby was revealed to be a spy for the Soviet Union. One day, Philby just disappeared. Montanelli later received a mysterious note from him saying, "Thanks for everything. Including your socks."

After the city of Santander was captured, Montanelli wrote that it was "a long military walk with only one enemy: the heat." This was different from the government's propaganda, which called the "battle" a glorious fight. In fact, Montanelli noted only one death in the Italian army, caused by a mule kick. He never reported this. Because of his article, he was sent back to Italy, put on trial, and kicked out of the Fascist party. He was also removed from the official organization for Italian journalists. When asked why he wrote such an "unpatriotic" article, he replied, "Show me a single casualty of that battle: because a battle without casualties is not a real battle!" He was found innocent.

Journalism During World War II

Reporting in Eastern and Northern Europe

Montanelli's strong opinions against fascism caused problems with Italian officials. His membership in the Fascist Party was taken away. This was a big deal because the party controlled everything in Italy. To help him, the culture minister offered Montanelli a job in Tallinn, Estonia, in 1938. He became the director of the Institute of Culture and taught Italian at the University of Tartu.

During this time, the director of Il Corriere della Sera, Aldo Borelli, asked Montanelli to be a foreign correspondent. Montanelli couldn't be officially hired as a journalist because of the fascist rules. He wrote for the newspaper from Estonia and Albania.

On September 1, 1939, Germany invaded Poland. Montanelli was sent to report from the front lines. Near Grudziądz, his car was stopped by German tanks. Adolf Hitler himself was on one of the tanks. When Hitler learned Montanelli was Italian, he jumped off the tank and gave a ten-minute speech. Montanelli was not allowed to report this event. The invasion of Poland happened so fast that it was over in weeks. Montanelli is believed to have reported on the Skirmish of Krojanty, creating a famous story from it.

Montanelli wasn't welcome in Italy, so he moved to Lithuania. He felt that more trouble was coming from the Soviet Union. He was right. Soon after he arrived in Kaunas, the Soviet Union demanded control over the Baltic countries. Montanelli traveled to Tallinn to see free Estonia one last time before it was invaded by the Soviet Union. By now, Montanelli was not popular in Italy or Germany because of his pro-Estonian and pro-Polish articles. He was also kicked out of the Soviet Union for being a foreigner. So, he had to cross the Baltic Sea to Helsinki, Finland.

In Finland, Montanelli wrote articles about the Lapps and reindeer. But this didn't last long. The Soviet Union demanded that Finland give up some of its land. The Finnish leaders refused, and it was clear war was coming. Montanelli couldn't write about the secret talks, but he interviewed the Finnish leader, Paasikivi, who told him everything except the secret details.

During the Winter War that followed, Montanelli wrote strong pro-Finnish articles. He reported from the front lines and from bomb-hit Helsinki. He wrote about brave acts, like the battle of Tolvajärvi, and Captain Pajakka, who with 200 Lapps faced 40,000 Russians. Back in Italy, people loved Montanelli's stories. But the fascist leaders, who were allied with the Soviet Union, were not happy. When Borelli, the newspaper director, was told to censor Montanelli's articles, he bravely replied, "Thanks to his articles the Corriere increased its sales from 500,000 to 900,000 copies: are you going to reimburse me?" After the Winter War ended, Gustaf Mannerheim, the Finnish military leader, personally thanked Montanelli for supporting Finland.

Invasion of Norway

Before returning to Italy, Montanelli saw the invasion of Norway. He was arrested by the German army because he was against their alliance with Italy. He escaped with help from his friend Vidkun Quisling. He then went north, where British and French troops were landing at Narvik. He met Major Adrian Carton de Wiart, who told him there were only 10,000 Allied troops, many untrained. No one seemed to know where their base was. The British wanted to attack, but the French wanted to stay put. After seeing the organized German invasion of Poland, Montanelli found this confusion worrying. When the Germans started bombing, the Allies had to leave quickly for England.

Balkans and Greece

When Italy entered the war in June 1940, Montanelli was sent to France and the Balkans. Then he covered the Italian military campaign in Greece and Albania. He later said he wrote very little from this front. He explained, "I remained at that front various months, writing almost nothing, a small reason was because I fell ill with typhus and a huge one because I refused to push as a glorious military campaign the quaking pummeling that we caught down there."

An article he wrote in September 1940 was seen as "defeatist" by the government's censors. They ordered the magazine to be shut down.

Arrest and Death Sentence

After seeing war and destruction, Montanelli decided to join the Italian resistance movement against the fascist government. He joined a secret group called Giustizia e Libertà. There, he met Sandro Pertini, who later became Italy's president.

The Germans eventually captured Montanelli again. He was put on trial and sentenced to death. In the San Vittore prison in Milan, he met Mike Bongiorno, who would become a famous Italian TV star. He also met General Della Rovere, a man believed to be on a secret mission for the Allies. In reality, this man was a thief and a German spy named Giovanni Bertoni. But Bertoni got so caught up in playing the role of a general that he refused to give information to the Germans. He was executed like a real enemy officer. After the war, Montanelli wrote a book about this story, Il generale Della Rovere (1959). It was later made into an award-winning movie directed by Roberto Rossellini.

Montanelli was saved at the end of 1944. Unknown people helped arrange his transfer to a prison in Verona. This transfer then turned into an escape to the Swiss border. The people who helped him remained a mystery for decades. Later, it was found that several groups were involved. Marshall Mannerheim, the Finnish leader, reportedly pressured his German allies. He told the German commander in Finland, "You are executing a gentleman." This led to an investigation from Berlin.

In 1945, while hiding in Switzerland, he published a novel called Drei Kreuze (Three Crosses). It later came out in Italian as Qui non-riposano (Here they do not rest).

Career After World War II

After the war, Montanelli continued his career at Il Corriere della Sera. He wrote moving articles from Hungary during the 1956 Hungarian Revolution. His reports inspired him to write a play, I sogni muoiono all'alba (Dreams Die at Dawn), which was later made into a film. In 1959, Montanelli made history by interviewing a Pope for the first time. Pope John XXIII said he chose Montanelli because he was an atheist, not a Catholic supporter.

In the mid-1960s, the ownership of Il Corriere della Sera changed. The newspaper then started to lean towards left-wing views. In 1972, the director, Giovanni Spadolini, was suddenly fired. Montanelli strongly criticized this in an interview. He said, "A director is not sent away like a thieving house-servant." He called the owners' actions "authoritarian" and "bullying."

Founding il Giornale and Later Years

After leaving Il Corriere della Sera, Montanelli started a new conservative newspaper called Il Giornale in 1973. He directed it until 1994, working with Enzo Bettiza.

On September 2, 1977, Montanelli was shot four times in the legs by two members of the Red Brigades. This happened outside the Milan office of Il Corriere della Sera. His surgeon was amazed that the four shots hit his "long, thin chicken legs" but completely missed any major blood vessels or nerves.

Silvio Berlusconi owned most of Il Giornale since 1977. When Berlusconi entered politics and started his new party, Forza Italia, Montanelli was pressured to support Berlusconi in his newspaper. Montanelli believed in his independence. So, he left and started a new newspaper called La Voce ("The Voice"). This name came from an old, famous newspaper. La Voce had a loyal but small group of readers and closed after about a year. Montanelli then returned to Il Corriere della Sera. In 1994, he received the International Editor of the Year Award from the World Press Review.

From 1995 to 2001, he was the chief letters editor for Il Corriere della Sera. He answered one letter a day on a page called "La Stanza di Montanelli" ("Montanelli's Room"). In his last years, Montanelli strongly opposed Silvio Berlusconi's politics. He was a mentor to many journalists and students, including Mario Cervi, Marco Travaglio, Paolo Mieli, Roberto Ridolfi, Andrea Claudio Galluzzo, Beppe Severgnini, and Roberto Gervaso.

Indro Montanelli passed away on July 22, 2001, at a clinic in Milan. The next day, Il Corriere della Sera published a letter on its front page titled: "Indro Montanelli's farewell to his readers."

Awards and Decorations

| Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic – awarded on December 15, 1995 |

![]() Commander, First Class, of the Order of the Lion of Finland

Commander, First Class, of the Order of the Lion of Finland

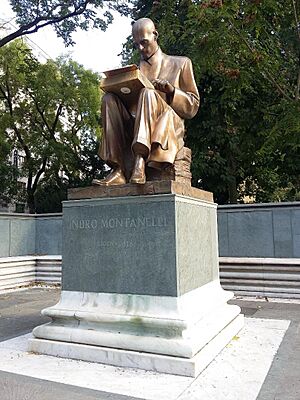

Legacy

Montanelli was called "The prince of journalism" by his fellow journalists while he was still alive. He earned great respect from people of all political views. He once wrote in his letters, "If you lack the holy fire inside, if you're not made for this work, if you lack a natural appendice with a typewriter... it's pointless to do this job." He left behind many first-hand reports and interviews with important historical figures. These included Charles de Gaulle, Benito Mussolini, Pope John XXIII, and Winston Churchill.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Indro Montanelli para niños

In Spanish: Indro Montanelli para niños

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |