Charles Martel facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Charles Martel |

|

|---|---|

|

|

19th-century sculpture at the Palace of Versailles

|

|

| Duke and Prince of the Franks | |

| Reign | 718–741 |

| Coronation | 718 |

| Predecessor | Pepin of Herstal |

| Successor | Pepin the Short |

| Mayor of the Palace of Austrasia | |

| Reign | 715–741 |

| Coronation | 715 |

| Predecessor | Theudoald |

| Successor | Carloman |

| Mayor of the Palace of Neustria | |

| Reign | 718–741 |

| Coronation | 718 |

| Predecessor | Ragenfrid |

| Successor | Pepin the Short |

| Ruler of the Franks | |

| Reign | 737–741 |

| Coronation | 737 |

| Predecessor | Theuderic IV |

| Successor | Childeric III |

| Born | 23 August 676 or 686, 688 or 690 Herstal, Belgium, then known as Austrasia |

| Died | 22 October 741 (aged 50–53, 55 or 65) Quierzy, Frankish Empire |

| Burial | Basilica of St Denis |

| Spouse |

|

| Issue |

|

| House | Pippinid Carolingian (founder) |

| Father | Pepin of Herstal |

| Mother | Alpaida |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

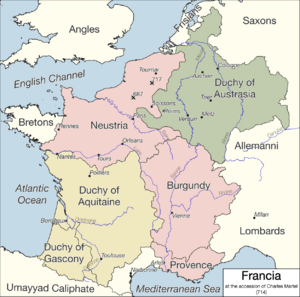

Charles Martel (born around 688 – died 22 October 741) was a powerful Frankish leader. He was a skilled military commander and politician. As the Duke and Prince of the Franks and Mayor of the Palace, he was the real ruler of Francia from 718 until his death.

Charles was the son of Pepin of Herstal, a Frankish statesman, and a noblewoman named Alpaida. Charles was also known as "The Hammer" (Martel in Old French). He took over his father's powerful role in Frankish politics. He continued his father's work, bringing back strong central government to Francia. He also led many military campaigns that made the Franks the main power in all of Gaul. A writer from his time called Charles "a warrior who was uncommonly effective in battle."

One of Charles Martel's most important victories was against an invading army from the Umayyad Caliphate at the Battle of Tours. At that time, the Umayyad Caliphate controlled most of Spain and Portugal. Charles is also known for helping to develop the Frankish system of feudalism, which was a way of organizing society.

Before he died, Charles divided Francia between his sons, Carloman and Pepin. Pepin later became the first king of the Carolingian dynasty. Charles's grandson, Charlemagne (Pepin's son), expanded the Frankish lands even more. Charlemagne became the first emperor in Western Europe since the fall of the Roman Empire.

Contents

Charles's Early Life

Charles, nicknamed "Martel" or "The Hammer," was the son of Pepin of Herstal and Alpaida. He had a brother named Childebrand, who later became a Frankish duke in Burgundy.

In the past, some historians called Charles "illegitimate." However, the rules for marriage and family were different in the 700s. It's likely that this idea came from Pepin's first wife, Plectrude, who wanted her own children to inherit Pepin's power.

After the reign of Dagobert I (629–639), the Merovingian kings lost much of their power. The Pippinid Mayors of the Palace became the true rulers of the Frankish kingdom of Austrasia. They controlled the royal money, gave out favors, and granted land in the name of the king, who was just a figurehead. Charles's father, Pepin of Herstal, managed to unite the Frankish lands by conquering Neustria and Burgundy. Pepin was the first to call himself Duke and Prince of the Franks, a title Charles later used.

Fighting for Power

In December 714, Pepin of Herstal died. Before his death, Pepin had named his young grandson, Theudoald, as his heir. This was because Pepin's son, Grimoald, had been killed. The nobles of Austrasia did not like this idea because Theudoald was only eight years old. To stop Charles from taking advantage of this unrest, Pepin's wife, Plectrude, had Charles put in prison in Cologne. This stopped a rebellion in Austrasia, but not in Neustria.

Civil War (715–718)

Pepin's death led to open fighting between his heirs and the Neustrian nobles. The Neustrians wanted to be independent from Austrasian control. In 715, Dagobert III named Ragenfrid as the Mayor of the Palace for Neustria. This was a clear sign of their independence. On September 26, 715, Ragenfrid's Neustrian forces defeated Theudoald's army at the Battle of Compiègne. Theudoald fled back to Cologne.

Before the end of that year, Charles Martel escaped from prison. The nobles of Austrasia quickly named him their mayor. In the same year, Dagobert III died. The Neustrians then made Chilperic II, a son of Childeric II, their new king.

Battle of Cologne

In 716, Chilperic and Ragenfrid led an army into Austrasia. They wanted to take the wealth of the Pippinid family in Cologne. The Neustrians teamed up with another invading army led by Redbad, King of the Frisians. They fought Charles near Cologne, which was still held by Plectrude. Charles did not have much time to gather his men or prepare. The Frisians held off Charles's forces while the king and his mayor attacked Plectrude in Cologne. She paid them a large part of Pepin's treasure to leave. After that, they left. The Battle of Cologne was the only defeat in Charles Martel's career.

Battle of Amblève

Charles retreated to the Eifel hills to gather and train his men. After preparing properly, in April 716, he surprised the victorious enemy army near Malmedy. They were on their way back to their own lands. In the Battle of Amblève, Martel attacked while the enemy was resting at midday. Some sources say he split his forces into several groups to attack from many sides. Others suggest he decided this wasn't needed because the enemy was so unprepared. Either way, the sudden attack made the enemy think they were facing a much larger army. Many of them ran away, and Martel's troops took their supplies. Charles's reputation grew a lot after this battle, and he gained more followers. Historians often see this battle as the turning point in Charles's fight for power.

Battle of Vincy

Charles took time to gather more men and prepare. By the next spring, Charles had enough support to invade Neustria. Charles sent a messenger to propose peace if Chilperic would recognize his rights as mayor of the palace in Austrasia. The refusal was expected, but it showed Martel's forces how unreasonable the Neustrians were. They met near Cambrai at the Battle of Vincy on March 21, 717. The victorious Martel chased the fleeing king and mayor to Paris. However, he was not ready to hold the city yet. He turned back to deal with Plectrude and Cologne. He took the city and scattered her supporters. Plectrude was allowed to retire to a convent. Theudoald lived until 741 under his uncle's protection. This was a kind act for those times, when showing mercy to a former jailer or a potential rival was rare.

Taking Full Control

After this success, Charles made Chlothar IV king of Austrasia. This was in opposition to Chilperic. Charles also removed Rigobert, the archbishop of Reims, and replaced him with Milo, who was a loyal supporter.

In 718, Chilperic reacted to Charles's growing power by making an alliance with Odo the Great, the duke of Aquitaine. Odo had become independent during the civil war in 715. But Charles defeated them again at the Battle of Soissons. Chilperic fled with Odo to the land south of the Loire. Ragenfrid fled to Angers. Soon, Chlotar IV died. Odo then handed over King Chilperic to Charles. In return, Charles recognized Odo's dukedom. Charles recognized Chilperic as king of the Franks. In exchange, the king officially confirmed Charles's role as mayor over all the kingdoms.

Wars (718–732)

Between 718 and 732, Charles made his power strong through many victories. After uniting the Franks under his rule, Charles wanted to punish the Saxons who had invaded Austrasia. So, in late 718, he destroyed their country up to the banks of the Weser, the Lippe, and the Ruhr. He defeated them in the Teutoburg Forest. This secured the Frankish border in the name of King Chlotaire.

When the Frisian leader Radbod died in 719, Charles took over West Frisia easily. The Frisians had been under Frankish rule but had rebelled after Pepin's death. When Chilperic II died in 721, Charles appointed Theuderic IV, the son of Dagobert III, as his successor. Theuderic was still a child and ruled from 721 to 737. Charles was now appointing the kings he supposedly served. These kings were just figureheads, often called rois fainéants (do-nothing kings). By the end of his reign, Charles didn't even bother to appoint any kings. At this time, Charles again marched against the Saxons. Then the Neustrians rebelled under Ragenfrid. They were easily defeated in 724. Ragenfrid gave up his sons as hostages to keep his county. This ended the civil wars of Charles's reign.

The next six years were spent making sure the Franks had authority over nearby groups. Between 720 and 723, Charles fought in Bavaria. The Agilolfing dukes there had slowly become independent rulers. They had recently allied with Liutprand the Lombard. Charles forced the Alemanni to join him, and Duke Hugbert submitted to Frankish rule. In 725, Charles brought back the Agilolfing Princess Swanachild as a second wife.

In 725 and 728, he entered Bavaria again. In 730, he marched against Lantfrid, Duke of Alemannia, who had also become independent. Charles killed him in battle. He forced the Alemanni to surrender to Frankish rule and did not appoint a new duke for them. This way, southern Germany became part of the Frankish kingdom again, just as northern Germany had in the first years of his rule.

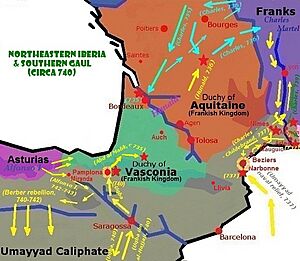

Aquitaine and the Battle of Tours (732)

In 731, after defeating the Saxons, Charles focused on the southern region of Aquitaine. He crossed the Loire River, breaking his treaty with Duke Odo. The Franks attacked Aquitaine twice and captured Bourges, though Odo later took it back. Some accounts say Odo asked for help from the new emirate of al-Andalus (Muslim Spain). Arab raids into Aquitaine had been happening since the 720s. The Chronicle of 754 records a victory for Odo in 721 at the Battle of Toulouse. It is more likely that this invasion was in revenge for Odo supporting a rebel Berber leader named Munnuza.

An army led by Abd al-Rahman ibn Abd Allah al-Ghafiqi marched north. After some small fights, they headed towards the rich city of Tours. Historian Paul Fouracre suggests their campaign was probably a long-distance raid, not the start of a full war. However, Charles's army defeated them at the Battle of Tours (also known as the Battle of Poitiers). This battle took place between the French cities of Tours and Poitiers. According to historian Bernard Bachrach, the Arab army, mostly on horseback, could not break through the Frankish foot soldiers. News of this battle spread. It might even be mentioned in Bede's Ecclesiastical History. However, it is not given much importance in Arabic writings from that time.

Even with his victory, Charles did not gain full control of Aquitaine. Odo remained duke until 735.

Wars (732–737)

Between his victory in 732 and 735, Charles reorganized the kingdom of Burgundy. He replaced the local counts and dukes with his loyal supporters. This strengthened his power. He was forced to invade independent Frisia again in 734 because of the actions of Bubo, Duke of the Frisians. In that year, he killed the duke at the Battle of the Boarn. Charles ordered the destruction of Frisian pagan shrines. He completely brought the people under his control, and the region was peaceful for twenty years afterward.

In 735, Duke Odo of Aquitaine died. Charles wanted to rule the duchy directly and went there to get the Aquitanians to submit. However, the nobles declared Odo's son, Hunald I of Aquitaine, as duke. Charles and Hunald eventually recognized each other's positions.

No King (737–741)

In 737, at the end of his campaigns in Provence and Septimania, the Merovingian king, Theuderic IV, died. Charles, who called himself maior domus (mayor of the palace) and princeps et dux Francorum (prince and duke of the Franks), did not appoint a new king. No one else claimed the throne either. The throne remained empty until Charles's death. The last four years of Charles's life were fairly peaceful. In 738, he made the Saxons of Westphalia surrender and pay tribute. In 739, he stopped a rebellion in Provence led by Maurontus.

Charles used this time of peace to bring the outer parts of his empire closer to the Frankish church. He created four new church regions in Bavaria (Salzburg, Regensburg, Freising, and Passau). He made Boniface the archbishop and head of the church for all of Germany east of the Rhine, with his main church in Mainz. Boniface had been under Charles's protection since 723. Boniface himself said that without Charles's help, he could not manage his church, protect his clergy, or stop people from worshipping idols.

In 739, Pope Gregory III asked Charles for help against Liutprand. But Charles did not want to fight his former ally and ignored the Pope's request. Still, the Pope asking for Frankish protection showed how powerful Charles had become. It also set the stage for his son and grandson to become very important in Italy.

Death and Passing of Power

Charles Martel died on 22 October 741, at Quierzy-sur-Oise in France. He was buried at Saint Denis Basilica in Paris.

A year before his death, Charles had divided his lands among his adult sons. To Carloman he gave Austrasia, Alemannia, and Thuringia. To Pippin the Younger he gave Neustria, Burgundy, Provence, and the areas of Metz and Trier. Grifo, another son, was given several lands throughout the kingdom, but this happened just before Charles died.

Charles Martel's Legacy

Early in his life, Charles Martel had many enemies within his own lands. He felt the need to appoint his own king, Chlothar IV. Later, however, the way Francia was ruled changed. A Merovingian king was no longer needed. Charles divided his kingdom among his sons without any major opposition.

Many historians believe Charles Martel set the stage for his son Pepin to become the Frankish king in 751. He also paved the way for his grandson Charlemagne to become emperor in 800. However, some historians like Paul Fouracre say that while Charles was "the most effective military leader in Francia," his career "finished on a note of unfinished business."

Family and Children

Charles Martel married twice. His first wife was Rotrude of Treves. They had the following children:

- Hiltrud

- Carloman

- Landrade

- Auda

- Pepin the Short

Most of these children married and had their own families. Hiltrud married Odilo I, the Duke of Bavaria. Auda married Thierry IV, a Count of Autun and Toulouse.

Charles also married a second time, to Swanhild. They had a child named Grifo.

Charles Martel also had children with Ruodhaid:

- Bernhard (born around 720–died 787)

- Hieronymus (born around 722 – died after 782)

- Remigius (died 771), who became the archbishop of Rouen.

Charles Martel's Reputation

Military Hero

For writers in the early Middle Ages, Charles Martel was famous for his military victories. For example, Paul the Deacon gave Charles credit for a victory against the Saracens that was actually won by Odo of Aquitaine.

By the 1700s, historians like Edward Gibbon began to see Charles Martel as the savior of Christian Europe. They believed he stopped a full-scale Islamic invasion. Gibbon wondered if, without Charles's victory, "Perhaps the interpretation of the Koran would now be taught in the schools of Oxford."

In the 1800s, German historian Heinrich Brunner suggested that Charles took church lands to pay for military changes. These changes, he argued, helped Charles defeat the Arab forces. However, historian Paul Fouracre argues that there isn't enough proof to show a major change in how the Franks fought or organized their army.

More recently, some historians argue that the importance of the Battle of Tours is often exaggerated. They say it might not have been as crucial for European history or for Charles Martel's reign as some believe.

Order of the Genet

In the 1600s, a story began that Charles Martel created the first official order of knights in France. In 1620, Andre Favyn claimed that after the Battle of Tours, Charles Martel's forces captured many genets (small animals raised for their fur) and their pelts. Charles Martel supposedly gave these furs to his army leaders, forming the first knightly order, called the Order of the Genet. This claim was then repeated in later books.

See also

In Spanish: Carlos Martel para niños

In Spanish: Carlos Martel para niños