Dark Ages (historiography) facts for kids

The Dark Ages is a term sometimes used for the Early Middle Ages. This period lasted from about the 5th to the 10th century in Western Europe. It followed the fall of the Western Roman Empire. Some people used this term to suggest that this time was marked by a decline in economy, learning, and culture.

The idea of a "Dark Age" came from an Italian scholar named Petrarch in the 1330s. He thought the centuries after the Roman Empire were "dark." This was because he compared them to the "light" of classical antiquity (ancient Greece and Rome). The term uses the idea of light versus darkness. It suggests the era was "dark" due to a lack of knowledge. Earlier and later times were seen as "light" because they had more understanding.

The phrase "Dark Age(s)" comes from the Latin saeculum obscurum. This term was first used by Caesar Baronius in 1602. He used it for a difficult time in the 10th and 11th centuries. Later, the idea grew to describe the entire Middle Ages as a time of little learning in Europe. This was between the fall of Rome and the Renaissance. It became very popular during the 18th-century Age of Enlightenment.

However, some people used the term to mean there were simply fewer written records from this time. As people learned more about the achievements of this era, scholars started to limit the term "Dark Ages" to just the Early Middle Ages (5th–10th century). Today, most modern scholars avoid the term entirely. They find it misleading and not accurate because it sounds too negative.

Contents

Understanding the "Dark Ages" Concept

Petrarch's View of History

The idea of a "Dark Age" began with the Italian scholar Petrarch in the 1330s. He wrote about the past, saying that even with mistakes, smart people still existed. He felt they were "surrounded by darkness." Christian writers, including Petrarch, often used 'light versus darkness' to describe 'good versus evil'.

Petrarch was the first to use this idea in a non-religious way. He saw classical antiquity as a time of great cultural achievements. He thought his own time lacked such achievements, so he called it an age of darkness.

From Italy, Petrarch saw the Roman period as a time of greatness. He traveled a lot, finding and sharing old Latin and Greek texts. He wanted to bring back the purity of the Latin language. Scholars of the Renaissance believed the 900 years before them were a time of slow progress. They saw history as developing through literature and art, not just religious events.

Petrarch believed history had two main parts. First, the classic period of Greeks and Romans. Second, a time of darkness, which he felt he lived in. Around 1343, he wrote that a "better age" would come after him. He hoped this "sleep of forgetfulness" would end. He believed that when the darkness was gone, future generations would see "pure radiance" again.

In the 15th century, historians Leonardo Bruni and Flavio Biondo created a three-part view of history. They used Petrarch's two ages and added a modern, "better age." They thought the world had entered this new age. Later, the term 'Middle Ages' was used to describe the period of supposed decline.

The Reformation's Perspective

During the Protestant Reformation in the 16th and 17th centuries, Protestants shared similar views with Renaissance scholars like Petrarch. They also added an anti-Catholic viewpoint. They saw classical antiquity as a golden time. This was not only because of its Latin literature but also because Christianity began then.

They promoted the idea that the 'Middle Age' was dark. They believed this was partly due to corruption within the Catholic Church. For example, they pointed to popes acting like kings and the worship of saints' relics.

Baronius and "Lack of Writers"

In response to the Protestants, Catholics created a different image. They showed the High Middle Ages as a time of social and religious peace. They argued it was not 'dark' at all. A key Catholic response was the Annales Ecclesiastici by Cardinal Caesar Baronius. This work covered the first twelve centuries of Christianity.

In Volume X, Baronius used the term "dark age" for the period between 888 and 1046. He wrote that this new age was "dark" because of a "lack of writers." He meant there were very few written records from this time.

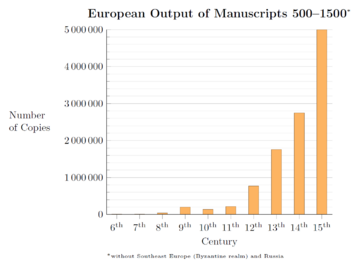

To show this "lack of writers," we can look at the number of Latin writings from different centuries. There was a big drop in written works from the 9th century to the 10th century. The 11th century showed some recovery, and the 12th century had even more writings. This suggests a "dark age" in terms of written records. This period was between the Carolingian Renaissance in the 9th century and the start of the Renaissance of the 12th century. There was also an earlier period with few writers in the 7th and 8th centuries. So, in Western Europe, two periods could be called 'dark ages' due to a lack of written sources. They were separated by the short but bright Carolingian Renaissance.

Baronius's idea of a 'dark age' spread in the 17th century. Some used the term neutrally to mean a lack of written records. Others used it negatively, which made the term less respected by many modern historians.

The Enlightenment's Criticism

During the Age of Enlightenment in the 17th and 18th centuries, many thinkers believed religion was against reason. They saw the Middle Ages, or "Age of Faith," as the opposite of their "Age of Reason." Thinkers like Voltaire and Edward Gibbon openly criticized the Middle Ages. They saw it as a time of social decline dominated by religion. Gibbon called the writings from this time "rubbish of the Dark Ages."

Like Petrarch, Enlightenment writers were criticizing the centuries before their own time. Petrarch's idea of darkness, which he used for a lack of non-religious achievements, became sharper. It took on a more anti-religious meaning.

Romanticism's New View

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the Romantics changed the negative view of the Enlightenment. They developed a love for medievalism. The word "Gothic" used to be a bad term, like "Vandal." But in the mid-18th century, English "Goths" like Horace Walpole started the Gothic Revival in art. This made people more interested in the Middle Ages.

For the next generation, the Middle Ages began to look like an "Age of Faith." This was a reaction to the Enlightenment's focus on rationalism. Romantics saw the Middle Ages as a Golden Age of chivalry. They felt a sense of nostalgia for this period. They saw it as a time of social harmony and spiritual inspiration. This was in contrast to the problems of the French Revolution and the changes from the Industrial Revolution. The Romantic view is still seen today in fairs and festivals that celebrate the period with 'merry' costumes and events.

The Romantics changed the Enlightenment's judgment. However, the period they admired was mostly the High Middle Ages. This was when the Church's power was at its peak. For many, the "Dark Ages" began to mean only the centuries right after the fall of Rome.

Modern Scholarly Use of the Term

Historians in the 19th century used the term "Dark Ages" widely. In 1860, Jacob Burckhardt wrote about the difference between the medieval 'dark ages' and the more enlightened Renaissance. The Renaissance, he felt, brought back the cultural and intellectual achievements of ancient times. The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) first listed "Dark Ages" in 1857. It defined it as a term for the Middle Ages, noting the "intellectual darkness" of the time. Since the Late Middle Ages overlap with the Renaissance, the term 'Dark Ages' became limited to specific times and places. For example, the 5th and 6th centuries in Britain, during the Saxon invasions, were called "the darkest of the Dark Ages."

From the mid-20th century, the term "Dark Ages" was questioned more and more. New studies in archaeology, history, and literature helped people understand the period better. In 1977, historian Denys Hay jokingly called them "the lively centuries which we call dark." A 2007 book on German literature called "the dark ages" a "popular if uninformed manner of speaking."

Most modern historians do not use "dark ages" anymore. They prefer terms like Early Middle Ages. However, when some historians do use "Dark Ages" today, they mean to describe the economic, political, and cultural challenges of the era. For others, the term is neutral. It means that events from this time seem 'dark' to us because there are very few historical records. For example, Robert Sallares noted the lack of sources about the First plague pandemic reaching Northern Europe. He said that "the epithet Dark Ages is surely still an appropriate description of this period."

However, from the late 20th century, other historians criticized even this neutral use of the term. First, it's hard to use the term neutrally because ordinary readers might still see it as negative. Second, 20th-century research greatly increased our understanding of the period's history and culture. It is no longer truly 'dark' to modern viewers. To avoid the negative judgment the term implies, many historians now avoid it completely.

Historians of early medieval Britain sometimes used it up to the 1990s. For example, a 1991 book was titled A Biographical Dictionary of Dark Age Britain. In 2020, historians John Blair, Stephen Rippon, and Christopher Smart noted: "The days when archaeologists and historians referred to the fifth to the tenth centuries as the 'Dark Ages' are long gone." They added that the items found from that time show a high level of skill.

Other Related Topics

- Conflict thesis and continuity thesis

- Greek dark ages after Late Bronze Age collapse

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |