Edward Gibbon facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Edward Gibbon

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait by Joshua Reynolds

|

|

| Member of Parliament for Lymington | |

| In office 1781–1784 |

|

| Preceded by | Samuel Salt Edward Eliot |

| Succeeded by | Samuel Salt Wilbraham Tollemache |

| Member of Parliament for Liskeard | |

| In office 1774–1780 |

|

| Preceded by | Harry Burrard Thomas Dummer |

| Succeeded by | Harry Burrard William Manning |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 8 May 1737 Putney, Surrey, England |

| Died | 16 January 1794 (aged 56) London, England |

| Political party | Whig |

| Alma mater | Magdalen College, Oxford |

| Signature |  |

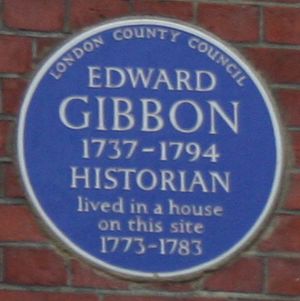

Edward Gibbon (born May 8, 1737 – died January 16, 1794) was an English historian, writer, and a member of Parliament. He is most famous for his big book, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. This huge work was published in six parts between 1776 and 1788. People remember it for its great writing, its clever use of humor, and how it used original historical records. It also openly discussed and questioned organized religion.

Contents

Edward Gibbon's Early Life (1737–1752)

Edward Gibbon was born in 1737 in Putney, England. His parents were Edward and Judith Gibbon. He had six brothers and sisters, but sadly, all of them died when they were very young. His grandfather, also named Edward, had lost a lot of money in a stock market crash called the "South Sea bubble" in 1720. But he managed to get much of his wealth back. This meant Gibbon's father inherited a good amount of money.

When Edward was young, he was often sick. He once said he was "a puny child, neglected by my Mother." At age nine, he went to Dr. Woddeson's school. Soon after, his mother passed away. He then lived with his beloved "Aunt Kitty," Catherine Porten, in a boarding house. He later said she saved him from his mother's lack of attention. She also taught him to read and helped him love books, which he said was "the pleasure and glory of my life." By 1751, Gibbon was already reading many books, especially history, which showed what he would do later in life.

Edward Gibbon's Career

Studying and Changing Beliefs (1752–1758)

In 1752, when he was 15, Gibbon went to Magdalen College, Oxford. He didn't enjoy his time there much, calling it "most idle and unprofitable." During this period, he became very interested in religious discussions. He converted to Roman Catholicism on June 8, 1753. This upset his father greatly.

Because of this, his father quickly sent him to Lausanne, Switzerland, to live with a Protestant pastor named Daniel Pavillard. There, Gibbon made two important friends: Jacques Georges Deyverdun and John Baker Holroyd. After about a year and a half, on Christmas Day, 1754, he changed his mind and became a Protestant again. He stayed in Lausanne for five years. This time was very important for his learning. He read many Latin books, studied how Swiss regions were governed, and read works by famous thinkers like John Locke.

A Love Story That Didn't Last

In Lausanne, Gibbon met the only love of his life, a young woman named Suzanne Curchod. She was the daughter of a pastor. They grew very close, and Gibbon even asked her to marry him. However, his father strongly disagreed with the marriage. Suzanne also didn't want to leave Switzerland.

So, the marriage didn't happen. Gibbon returned to England in 1758 and felt he had to obey his father. He wrote, "I sighed as a lover, I obeyed as a son." He stopped contacting Suzanne, even though she said she would wait for him. They saw each other a few more times later, but their romantic relationship ended. Suzanne later married Jacques Necker, who became a finance minister in France.

Early Success and Travels (1758–1765)

After returning to England, Gibbon published his first book in 1761, called Essai sur l'Étude de la Littérature. This book brought him some fame, especially in Paris. From 1759 to 1770, Gibbon also served in the South Hampshire Militia, a local army group.

In 1763, he traveled back to Lausanne and then went on a "Grand Tour" of Italy. He arrived in Rome in October 1764. It was in Rome that he first thought about writing his famous history of the Roman Empire. He was inspired by seeing the ruins of the city.

Later Career and Writing (1765–1776)

Early Writing Attempts

In June 1765, Gibbon went back to his father's house and stayed there until his father died in 1770. He found these years difficult but tried to stay busy by starting to write history books. He began a book called History of Switzerland, showing his love for the country. But he was very critical of his own work and never finished it. After he died, parts of it were published.

He also wrote another two-volume work called Memoires Litteraires de la Grande Bretagne. This book described the literary and social life in England at the time. However, it was not very successful and didn't become well-known.

After his father's death, Gibbon inherited enough money to live comfortably in London. He joined important social clubs, including Dr. Johnson's Literary Club. In 1774, he became a Freemason.

Also in 1774, he became a Member of Parliament for Liskeard. He was a quiet member, usually supporting the government without much debate. He lost this seat in 1780 but became an MP again in 1781 for Lymington. His political role didn't stop him from making progress on his writing.

His Famous Book: The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1776–1788)

After many changes and hard work, the first part of his greatest achievement, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, was published on February 17, 1776. People loved it, and three editions were quickly sold. Gibbon earned a lot of money from it. His fame grew very quickly and lasted a long time. Famous historian David Hume praised the first volume, saying it was worth ten years of work.

Volumes II and III came out in 1781. Volumes IV, V, and VI were finished between 1784 and 1787 while Gibbon was back in Lausanne. He worked hard to finish the project, and it was completed in June 1787. The last three volumes were published in May 1788, on his 51st birthday. Many important people, like Adam Smith and Horace Walpole, praised these later volumes. Adam Smith told Gibbon that his book made him "the very head of the whole literary tribe at present existing in Europe." In 1788, he was chosen as a Fellow of the Royal Society, a very respected group of scientists.

Gibbon also took an interest in his friend Lord Sheffield's daughter, Maria. He offered to teach her himself. He helped her become a well-educated and confident young woman.

Edward Gibbon's Later Life (1789–1794)

The years after Gibbon finished his great book were sad and full of health problems. He returned to London to help publish the last volumes. In 1789, he went back to Lausanne but was very sad to learn that his friend Deyverdun had died. Deyverdun had left his home to Gibbon in his will.

Gibbon lived quietly there, enjoying local society. He was very worried about the French Revolution. In 1793, he heard that Lady Sheffield, his friend's wife, had died. He immediately left Lausanne to comfort his grieving friend. His own health got much worse in December.

Edward Gibbon suffered from gout and a severe swelling condition. He had several operations to try and fix it, but they didn't work for long. In early January, a final operation led to a serious infection that spread throughout his body. He died from this infection.

Edward Gibbon, a great thinker of the Enlightenment, died on January 16, 1794, at age 56. He was buried in the Sheffield Mausoleum in Fletching, East Sussex. He had been staying with his good friend, Lord Sheffield, when he passed away. Gibbon left most of his money to his cousins. His will stated that his library of 6,000 books should be sold. It was bought by William Beckford.

Edward Gibbon's Legacy

Edward Gibbon's main idea about why the Roman Empire fell was that it was because of Christianity. He believed that a lot of money that could have been used for the state was instead given to the Church. He also thought that some Christians chose a monastic life, which meant they stopped supporting the empire. And he suggested that Christianity's focus on peace made fewer people join the military. However, many historians today do not fully agree with these reasons. They point out that the empire spent money on religion before Christianity too, and the number of people becoming monks or leaving the military was not large enough to cause the empire's fall.

Gibbon's book was also criticized for its strong views on Christianity in two of its chapters. Some people even wanted the book banned. They felt he disrespected Christian beliefs by treating the Church like any other historical event, without special religious explanations. He was also criticized for saying the Church replaced the great Roman culture in a destructive way and for promoting religious intolerance.

Gibbon expected some criticism from the Church, but the attacks were harsher than he thought. He wrote a book called Vindication in 1779 to defend his work. He also faced accusations of being against the Jewish faith.

How Gibbon Influenced Others

Edward Gibbon is seen as an important figure of the Age of Enlightenment. This was a time when people focused on reason and science. He famously said that the Middle Ages showed "the triumph of barbarism and religion." However, he also agreed with Edmund Burke, a conservative thinker, who was against the radical changes of the French Revolution.

Gibbon's writing style is highly praised for its cleverness and sharp humor. Winston Churchill, a famous British leader, said that he "devoured Gibbon" and loved his book. Churchill even tried to write in a similar style to Gibbon, aiming for "a vivid historical narrative."

Gibbon was also unusual for his time because he always tried to use original historical sources instead of just reading what others had written. He said, "I have always endeavoured... to draw from the fountain-head." This means he wanted to get information directly from the first records.

Gibbon's writing and ideas have influenced many other writers. Besides Churchill, science fiction writer Isaac Asimov said he used Gibbon's Decline and Fall as inspiration for his Foundation Trilogy.

Books Written by Edward Gibbon

- Essai sur l’Étude de la Littérature (1761)

- Critical Observations on the Sixth Book of [Vergil's] 'The Aeneid' (1770)

- The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (Volume I, 1776; Volumes II, III, 1781; Volumes IV, V, VI, 1788–1789)

- A Vindication of some passages in the fifteenth and sixteenth chapters of the History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1779)

- Mémoire Justificatif pour servir de Réponse à l’Exposé, etc. de la Cour de France (1779)

Other Writings by Edward Gibbon

- "Lettre sur le gouvernement de Berne" (Letter about the government of Berne)

- Mémoires Littéraires de la Grande-Bretagne (Literary Memoirs of Great Britain), co-written with Georges Deyverdun (2 volumes, 1767–1768)

- Miscellaneous Works of Edward Gibbon, Esq., edited by John Lord Sheffield (published after his death, 1796, 1814, 1815). This includes his Memoirs of the Life and Writings of Edward Gibbon, Esq..

- Autobiographies of Edward Gibbon, edited by John Murray (1896)

- The Private Letters of Edward Gibbon, edited by Rowland E. Prothero (2 volumes, 1896)

- The works of Edward Gibbon, Volume 3 (1906)

- Gibbon's Journal to 28 January 1763, edited by D.M. Low (1929)

- Le Journal de Gibbon à Lausanne, edited by Georges A. Bonnard (1945)

- Miscellanea Gibboniana, edited by G.R. de Beer, L. Junod, G.A. Bonnard (1952)

- The Letters of Edward Gibbon, edited by J.E. Norton (3 volumes, 1956)

- Gibbon's Journey from Geneva to Rome, edited by G.A. Bonnard (1961)

- Edward Gibbon: Memoirs of My Life, edited by G.A. Bonnard (1969)

- The English Essays of Edward Gibbon, edited by Patricia Craddock (1972)

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Edward Gibbon para niños

In Spanish: Edward Gibbon para niños

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |