Renaissance of the 12th century facts for kids

The Renaissance of the 12th century was a special time in Europe, marking the start of the High Middle Ages. It was a period of big changes in how people lived, how governments worked, and how money was made. There was also a huge burst of new ideas in Western Europe, especially in philosophy and science.

These changes helped set the stage for even bigger achievements later on. For example, the famous Italian Renaissance in the 1400s, with its amazing art and literature, and the Scientific Revolution in the 1600s, which changed how we understand the world.

After the Western Roman Empire fell, Europe lost a lot of its scientific knowledge. But things started to improve when Europeans had more contact with the Islamic world. Islamic thinkers and scientists had kept and built upon the old Greek works, especially those by Aristotle and Euclid. When these works were translated into Latin, they greatly boosted European science.

During the 1100s, a new way of thinking called Scholasticism became popular. It used a careful, logical approach to understand religious ideas. This movement grew stronger with new Latin translations of works by ancient and medieval Islamic and Jewish philosophers like Avicenna, Maimonides, and Averroes.

The early 1100s also saw a renewed interest in classic Latin books and writing. Important schools at cathedrals like Chartres and Canterbury became centers for learning. Later, Aristotle's logic became very important in the new universities. It even took over from Latin literature for a while, until it was brought back by Petrarch in the 14th century.

Contents

Earlier European Revivals

The path for this rebirth of learning was prepared by European kings who started to make their kingdoms stronger and more organized. This process began with Charlemagne, who was King of the Franks from 768 to 814 and Holy Roman Emperor from 800 to 814. Charlemagne loved education, and this led to many new churches and schools where students had to learn Latin and Greek. This time is often called the Carolingian Renaissance.

Another "renaissance" happened during the rule of Otto I (also known as Otto the Great). He was King of the Saxons from 936 to 973 and Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire from 962. Otto successfully united his kingdom and gained the power to choose bishops and archbishops. This close connection with the most educated people in his kingdom led to many new improvements. Because of this, Otto's time is called the Ottonian Renaissance.

The Renaissance of the 12th century is seen as the third and final of these medieval renaissances. However, the 12th-century renaissance was much deeper and more widespread than the Carolingian or Ottonian periods. Some historians even say that calling the earlier periods "renaissances" might be misleading, as they were more about the rulers themselves than a true change in society.

Why the 12th Century Was Special

A famous historian named Charles Homer Haskins was one of the first to write a lot about this renaissance, which began around 1070. He described the 12th century in Europe as a time of "fresh and vigorous life."

He noted that this period saw:

- The Crusades, which were religious wars.

- The growth of towns and cities.

- The start of the first organized governments in the West.

- The peak of Romanesque art and the beginning of Gothic style.

- The rise of writing in everyday languages, not just Latin.

- A renewed interest in old Latin books and poetry, and Roman law.

- The rediscovery of Greek science, with new ideas from Arabic scholars, and much of Greek philosophy.

- The creation of the first European universities.

The 12th century truly left its mark on higher education, on scholarly thinking, on legal systems, on architecture, and on literature.

The English art historian Kenneth Clark also believed that Western Europe's first "great age of civilization" started around the year 1000. He wrote that from 1100, huge abbeys and cathedrals were built. They were decorated with sculptures, tapestries, and mosaics, showing off some of the greatest art ever. This was a big change from the simple, crowded lives most people lived. Abbot Suger of the Abbey of St. Denis was an important supporter of Gothic architecture. He believed that loving beauty could bring people closer to God. Clark called this idea "the intellectual background of all the sublime works of art of the next century."

Bringing Knowledge Back: The Translation Movement

Translating texts from other cultures, especially ancient Greek works, was a very important part of the 12th-century Renaissance. It was also important for the later Renaissance in the 1400s. In the 12th century, scholars mostly focused on translating Greek and Arabic works about natural science, philosophy, and mathematics. Later, in the 1400s, the focus shifted more to stories and historical texts.

Trade and Business Growth

The Crusades brought many Europeans into contact with new technologies and luxurious goods from Byzantium for the first time in centuries. Crusaders returning home brought back small treasures, which made people want more trade. Powerful Italian cities like Genoa and Venice started to control trade between Europe, Muslim lands, and Byzantium across the Mediterranean Sea. They developed clever ways of doing business and banking. Cities like Florence became major centers for this financial activity.

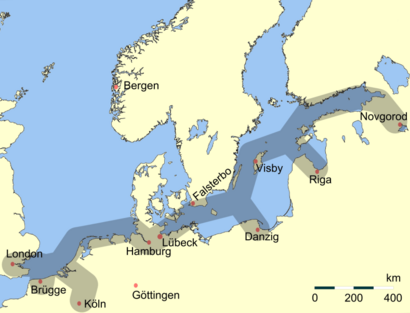

In Northern Europe, the Hanseatic League began in the 1100s, after the city of Lübeck was founded in 1158–1159. Many northern cities in the Holy Roman Empire joined the Hanseatic League, including Hamburg, Stettin, Bremen, and Rostock. Other Hanseatic cities outside the Holy Roman Empire included Bruges, London, and the Polish city of Danzig (Gdańsk). The league also had trading posts in Bergen and Novgorod. During this time, Germans also started settling in Eastern Europe, in areas like Prussia and Silesia.

In the mid-1200s, the "Pax Mongolica" (Mongol Peace) made land trade routes between China and West Asia active again. These routes had been quiet for a few centuries. After the Mongols entered Europe in 1241, the Pope and some European rulers sent travelers to the Mongol court. These included William of Rubruck and Giovanni da Pian del Carpini. While their accounts were written in Latin for their sponsors, the famous Italian traveler Marco Polo wrote his story in French around 1300. This made his adventures in China available to many more Europeans.

Science and New Discoveries

After the Western Roman Empire fell, Western Europe faced many challenges. Most scientific writings from classical antiquity, which were in Greek or Latin, were lost or hard to find. Science education in the Early Middle Ages was very limited, based on only a few Latin translations of old Greek texts. Only the Christian church kept copies of these writings, sharing them with other churches.

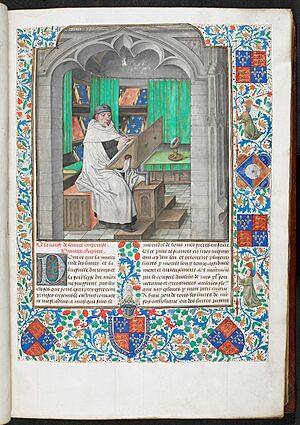

This situation changed during the 12th-century renaissance. For centuries, popes had sent educated church members to European kings. Kings were often unable to read or write. These educated clerics became experts in subjects like music, medicine, or history. They joined the king's court, teaching the king and his children. This helped spread knowledge throughout the Middle Ages. The church kept classic scriptures in scrolls and books in many writing rooms across Europe. This preserved old knowledge and gave European kings access to important information. In return, kings were encouraged to build monasteries, which served as orphanages, hospitals, and schools, benefiting society.

More contact with the Islamic world in Muslim Spain and Southern Italy, along with the Crusades and the Reconquista, and increased contact with Byzantium, allowed Western Europeans to find and translate works by Greek and Islamic philosophers and scientists. The works of Aristotle were especially important. Several translations of Euclid were made, but detailed explanations didn't appear until the mid-1200s.

The growth of medieval universities greatly helped in translating and spreading these texts. Universities created a new system needed for scientific communities. In fact, European universities made many of these texts central to their studies. This means that "the medieval university focused much more on science than its modern descendants do."

By the early 1200s, there were good Latin translations of some ancient Greek scientific works. These texts were studied and expanded upon, leading to new ideas about the universe. This revival influenced the scientific work of people like Robert Grosseteste.

Amazing New Technologies

During the High Middle Ages in Europe, there were many new inventions that helped the economy grow.

Historians like Alfred Crosby have written about this technological revolution. Here are some key inventions and improvements:

- The first written record of a windmill is from Yorkshire, England, in 1185.

- Paper making started in Spain around 1100. From there, it spread to France and Italy during the 1100s.

- The magnetic compass helped sailors navigate. It was first mentioned in Europe in the late 1100s.

- The ancient Greek astrolabe returned to Europe through Islamic Spain.

- The oldest known picture of a stern-mounted rudder (for steering ships) in the West is from church carvings around 1180.

- The dry compass was invented in 12th-century France.

- The mechanical clock was invented in the 13th century.

Latin Literature Flourishes

The early 12th century saw a renewed interest in studying classic Latin writings, both prose and poetry. This happened even before Greek philosophy was widely translated into Latin. The cathedral schools at Chartres, Orleans, and Canterbury were important centers for Latin literature. They had famous scholars, like John of Salisbury, who became a bishop. He greatly admired Cicero for his philosophy, language, and humanistic ideas. Latin scholars at this time had and read almost all the Latin authors we know today, such as Ovid, Virgil, Terence, Horace, Seneca, and Cicero.

However, this Latin revival didn't last forever. While some religious people didn't like old Roman literature, historian Haskins argued that it was "not religion but logic" that caused the change. Specifically, Aristotle's "New Logic" in the mid-1100s became very important. This focus on logic pushed aside the study of Latin literature, speeches, and poetry. The new universities became centers for Aristotelian studies, and the Latin humanist tradition faded until Petrarch brought it back in the 14th century.

Roman Law Returns

Studying the Digest, a collection of Roman laws, was the first step in bringing back Roman legal ideas. This helped establish Roman law as the basis for civil law in Western Europe. The University of Bologna, which is the world's oldest continuously operating university, was Europe's main center for legal studies during this time.

Scholasticism: A New Way of Thinking

A new way of thinking about Christian theology developed during this period. It was led by "scholastics" or "schoolmen" who used a more systematic and logical approach to religious questions. This movement was first inspired by studying Boethius's writings on Aristotle's logic and Calcidius's comments on Plato's Timaeus. These were the main ways people knew about these two philosophers in the Latin West. Thinkers like St Anselm and scholars from the School of Chartres helped start this.

The movement grew stronger as more works by ancient scholars became available through new Latin translations. These translations came from places like the Papal States (by Constantine the African), the Toledo School of Translators in Castile, and Constantinople (by James of Venice).

These same routes, especially in Spain, also brought in medieval Islamic and Jewish philosophical ideas, particularly from Maimonides, Avicenna, and Averroes. France, especially the University of Paris, became a center for these new texts. Later, scholastic scholars of the 1200s, like Albertus Magnus, Bonaventure, and Thomas Aquinas, became respected church teachers. They used logical study to support existing religious beliefs.

Arts and Creativity

The 12th-century renaissance also saw a renewed interest in poetry. Poets at this time wrote much more than during the earlier Carolingian Renaissance. They mostly wrote in their own native languages. The topics varied greatly, including epic stories, lyrical songs, and dramatic plays. Poetry forms became more flexible, moving beyond the old classical rules. Also, the line between religious and non-religious poetry became less clear. For example, the Goliards were known for their funny and sometimes rude parodies of religious texts.

These new ways of writing poetry helped lead to the rise of literature written in everyday languages, which often preferred these newer rhythms and structures.

|

See also

- Continuity thesis

- Crisis of the Late Middle Ages

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |