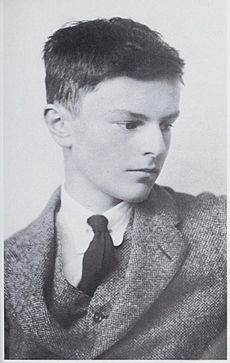

Kenneth Clark facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

The Lord Clark

|

|

|---|---|

Clark photographed in 1934 by Howard Coster

|

|

| Born |

Kenneth Mackenzie Clark

13 July 1903 |

| Died | 21 May 1983 (aged 79) |

| Alma mater | Trinity College, Oxford |

| Occupation |

|

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children | Alan, Colette and Colin |

Kenneth Mackenzie Clark, Baron Clark (born 13 July 1903 – died 21 May 1983) was a famous British art historian, museum boss, and TV presenter. In the 1930s and 1940s, he ran two important art galleries. Later, he became well-known on television, hosting many art shows in the 1950s and 1960s. His most famous series was Civilisation in 1969.

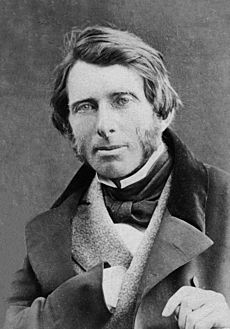

Kenneth Clark came from a wealthy family and learned about art from a young age. He was inspired by the writer John Ruskin, who believed everyone should be able to enjoy great art. After working with art expert Bernard Berenson, Clark became the director of the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford when he was just 27. Three years later, he took charge of Britain's National Gallery. During his 12 years there, he made the gallery more welcoming for everyone. During the Second World War, when the art was moved for safety, Clark allowed the building to be used for daily concerts. These concerts were a big help for people's spirits during the Blitz.

After the war, Clark was a professor of fine art at Oxford. He then surprised many by becoming the head of the UK's first commercial television network. After it successfully started, he agreed to create and present art programs. These shows made him a household name in Britain. He was then asked to make the first color TV series about art, Civilisation, which first aired in 1969.

Clark received many awards. He was made a knight at the young age of 35. Thirty years later, he was given a special title as a life peer just before Civilisation was shown. Years after he passed away, an exhibition at Tate Britain in London celebrated his work. This made a new generation of critics look at his career again. People had different opinions about his art choices, especially when he tried to identify who painted old artworks. However, everyone agreed he was a great writer and loved to share art with many people. Both the BBC and the Tate have called him one of the most important people in British art in the 20th century.

Contents

Kenneth Clark's Early Life and Career

Growing Up with Art

Kenneth Clark was born in London. He was the only child of Kenneth Mackenzie Clark and his wife, Alice. The Clark family was Scottish and became very rich from the textile business. Kenneth Clark's great-great-grandfather invented the cotton spool. The Clark Thread Company grew into a huge business. Kenneth Clark senior worked for a short time as a director of the company. He retired in his mid-twenties as a very wealthy man.

The Clarks owned country homes in Suffolk and Argyll. They also spent winters on the French Riviera. Kenneth senior was a sportsman and enjoyed gambling. Kenneth Clark junior felt he had little in common with his father, but he still loved him. His mother, Alice, was shy and quiet. However, a kind nanny gave young Kenneth a lot of affection. Since he was an only child and not very close to his parents, Clark's childhood was often lonely, but he was generally happy. He remembered taking long walks and talking to himself. He believed this habit helped him later as a TV presenter. He said, "Television is a form of talking to yourself."

Clark senior collected some pictures, and young Kenneth was allowed to arrange them. He became good at drawing and won several school prizes for it. When he was seven, he went to an exhibition of Japanese art in London. This experience greatly shaped his love for art. He remembered being "speechless with joy" and feeling like he had entered a new world.

School and University Days

Clark went to Wixenford School and then to Winchester College from 1917 to 1922. Winchester College was known for its tough studies and its love for sports, which Clark didn't enjoy much. But the school also encouraged students to be interested in the arts. The headmaster, Montague Rendall, loved Italian painting and sculpture. He inspired Clark and many others to appreciate the works of Giotto, Botticelli, Bellini, and other Italian artists. The school library had all the writings of John Ruskin. Clark read them eagerly, and they influenced him for the rest of his life. Ruskin's ideas about art and his forward-thinking social beliefs stayed with Clark.

From Winchester, Clark won a scholarship to Trinity College, Oxford. There, he studied modern history. He graduated in 1925 with a good degree. People expected him to get a top degree, but he didn't focus only on history. His interests had already turned completely to studying art.

While at Oxford, Clark was very impressed by the lectures of Roger Fry. Fry was an important art critic who organized the first Post-Impressionism art shows in Britain. Fry helped Clark understand modern French painting, especially the work of Cézanne. Clark also caught the eye of Charles F. Bell, who was in charge of the Fine Art Department at the Ashmolean Museum. Bell became a mentor to Clark. He suggested that Clark write about the Gothic revival in architecture for his advanced degree. At that time, this topic was not popular. No serious book had been written about it since the 1800s. Even though Clark's main interest was the Renaissance, his admiration for Ruskin, who supported the neo-Gothic style, drew him to the topic. He didn't finish the degree, but he later turned his research into his first full book, The Gothic Revival (1928). In 1925, Bell introduced Clark to Bernard Berenson. Berenson was a very important expert on the Italian Renaissance. He advised major museums and art collectors. Berenson was updating his book Drawings of the Florentine Painters, and he invited Clark to help. This project took two years and happened while Clark was still studying at Oxford.

Starting His Art Career

In 1929, because of his work with Berenson, Clark was asked to organize the large collection of Leonardo da Vinci drawings at Windsor Castle. That same year, he helped organize an exhibition of Italian painting that opened in January 1930. He and his co-organizer, Lord Balniel, brought masterpieces that had never been seen outside Italy before. Many of these came from private collections. The exhibition showed Italian art from the mid-1200s to the late 1800s. It was very popular with the public and critics. This raised Clark's profile, but he later regretted that the Italian leader Benito Mussolini used the exhibition for his own purposes. Mussolini had helped make many of the paintings available. Some important people in the British art world didn't like the exhibition. Bell was one of them, but he still thought Clark was the best person to take over his job at the Ashmolean.

Clark wasn't sure if he wanted to be a museum manager. He enjoyed writing and would have preferred to be a scholar rather than a director. Still, when Bell retired in 1931, Clark agreed to take his place at the Ashmolean. Over the next two years, Clark oversaw the building of an addition to the museum. This gave his department a better space. The money for this project came from an anonymous donor, who was later revealed to be Clark himself. A later museum curator said that Clark would be remembered for his time there. He said Clark, "with his characteristic mix of confidence and energy, changed both the collections and how they were shown."

Leading the National Gallery

Making Art Accessible

In 1933, the director of the National Gallery in London, Sir Augustus Daniel, was about to retire. The assistant director, W. G. Constable, who was expected to take over, had moved to a new art institute. The National Gallery was having many problems with its staff and trustees. Lord Lee, the head of the trustees, convinced the prime minister, Ramsay MacDonald, that Clark would be the best choice. Clark was young, only 30, and wasn't sure he wanted the job. He accepted, but he wrote to Berenson that he would have to be "a professional entertainer to the landed and official classes" while also managing a large museum.

Around the same time, Clark turned down an offer from King George V to be the Surveyor of the King's Pictures. He felt he couldn't do both jobs well. But the King, with Queen Mary, went to the National Gallery and convinced Clark to change his mind. Clark held this royal job for the next ten years.

Clark believed that everyone should be able to see and enjoy fine art. At the National Gallery, he started many projects to achieve this. The Burlington Magazine said that Clark "put all his understanding and imagination into making the National Gallery a more friendly place where visitors could enjoy a great collection of European paintings." He rearranged rooms and improved frames. By 1935, he had a lab installed and electric lighting, which meant the gallery could stay open in the evenings for the first time. They also started cleaning paintings, even though some people didn't like cleaning old pictures. As an experiment, the glass was removed from some paintings. For several years, he opened the gallery two hours earlier than usual on the day of the FA Cup Final. This was for people coming to London for the match.

Clark also wrote and gave lectures during this time. His detailed catalog of Leonardo da Vinci's drawings from the royal collection, which he started in 1929, was published in 1935. It received excellent reviews. Eighty years later, Oxford Art Online called it "a work of strong scholarship, whose findings have stood the test of time." Another book by Clark in 1935 upset some modern artists. In an essay called "The Future of Painting," he criticized surrealist and abstract artists for saying they represented the future of art. He thought both styles were too fancy and too specific. He believed good art must be understandable to everyone and based on the real world. In the 1930s, Clark was a popular lecturer. He often used his research for his talks as the basis for his books. In 1936, he gave lectures at Yale University. From these talks came his book about Leonardo, published three years later. It also received much praise.

The Burlington Magazine, looking back at Clark's time at the gallery, highlighted some important artworks bought under his leadership. These included seven panels by Sassetta from the 1400s, four works by Giovanni di Paolo from the same period, Niccolò dell'Abate's The Death of Eurydice from the 1500s, and Ingres' Madame Moitessier from the 1800s. Other important purchases were Rubens's Watering Place, Constable's Hadleigh Castle, Rembrandt's Saskia as Flora, and Poussin's The Adoration of the Golden Calf.

One of Clark's less successful decisions as director was buying four paintings from the early 1500s, now known as Scenes from Tebaldeo's Eclogues. He saw them in 1937 at a dealer's in Vienna. Against the advice of all his staff, he convinced the trustees to buy them. He believed they were by Giorgione, whose work was not well represented in the gallery. The trustees approved spending £14,000 of public money, and the paintings were displayed with much excitement. His staff did not agree that Giorgione painted them. Within a year, research proved the paintings were by Andrea Previtali, a less famous artist from Giorgione's time. The British newspapers complained about the waste of taxpayer money. Clark's reputation suffered, and his relationship with his staff became even more difficult.

Wartime Efforts

When war with Germany seemed likely in 1939, Clark and his team had to figure out how to protect the National Gallery's collection from bombs. They decided all the artworks had to be moved out of central London. One idea was to send them to Canada for safety. But by then, the war had started, and Clark worried about submarines attacking the ships. He was happy when the prime minister, Winston Churchill, said no to the idea: "Hide them in caves and cellars, but not one picture shall leave this island." An old slate mine in north Wales was chosen as the storage place. Special storage areas were built to protect the paintings. By carefully watching the collection, they learned important things about controlling temperature and humidity. This helped care for and display the art when it returned to London after the war.

With an empty gallery, Clark thought about joining the navy. But he was asked to join the new Ministry of Information. There, he was put in charge of the film division. Later, he was promoted to control home publicity. He created the War Artists' Advisory Committee. He convinced the government to hire many official war artists. About 200 artists worked under Clark's plan. These "official war artists" included Edward Ardizzone, Paul and John Nash, Mervyn Peake, John Piper, and Graham Sutherland. Other artists hired for shorter times included Jacob Epstein, Laura Knight, L. S. Lowry, Henry Moore, and Stanley Spencer.

Even though the paintings were stored away, Clark kept the National Gallery open to the public during the war. He hosted a famous series of lunchtime and early evening concerts. These concerts were the idea of the pianist Myra Hess. Clark loved the idea, seeing it as a way for the building to be "used again for its true purposes, the enjoyment of beauty." There was no need to book tickets in advance. People could eat their sandwiches and walk in or out during breaks. The concerts were an instant and huge success. The Musical Times said, "Countless Londoners and visitors to London... came to look on the concerts as a haven of sanity in a distraught world." A total of 1,698 concerts were held, with over 750,000 people attending. Clark also started showing a "picture of the month" from storage, with information about it. This "picture of the month" idea continued after the war and is still done today.

In 1945, after making sure the art collections were back in the National Gallery, Clark resigned as director. He wanted to focus on writing. During the war, he had published little. He wrote a small book about Constable's The Hay Wain (1944) for the gallery. From a lecture he gave in 1944, he published a short book about Leon Battista Alberti's On Painting (1944). The next year, he wrote an introduction and notes for a book on Florentine paintings. These three publications together were less than eighty pages long.

Post-War Career and Broadcasting

Teaching and Public Service

In July 1946, Clark was appointed a professor of fine art at Oxford for three years. This job required him to give eight public lectures each year on the "History, Theory, and Practice of the Fine Arts." The first person to hold this professorship was Ruskin. Clark's first lectures were about Ruskin's time in the role. James Stourton, Clark's official biographer, believes this was the most rewarding job Clark ever had. He notes that during this time, Clark became Britain's most sought-after lecturer. He also wrote two of his best books: Landscape into Art (1947) and Piero della Francesca (1951). By this point, Clark no longer wanted a career in pure academic study. He saw his role as sharing his knowledge and experience with the general public.

Clark served on many official committees during this period. He also helped organize an important exhibition in Paris of works by his friend and student, Henry Moore. He liked modern painting and sculpture more than much of modern architecture. He admired architects like Giles Gilbert Scott and Frank Lloyd Wright, but he found many modern buildings to be just okay. Clark was among the first to realize that private wealthy people could no longer fully support the arts. During the war, he was an important member of the state-funded Council for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts. When it was reformed as the Arts Council of Great Britain in 1945, he was invited to be on its executive committee and to lead its arts panel.

In 1953, Clark became the chairman of the Arts Council. He held this position until 1960, but he found it frustrating. He felt he was mostly just a figurehead. Also, he worried that the way the council funded the arts might harm the unique style of the artists it supported.

Moving to Television: Administrator (1954–1957)

The year after becoming chairman of the Arts Council, Clark surprised many people by accepting the chairmanship of the new Independent Television Authority (ITA). This organization was set up by the government to start ITV, which was commercial television funded by ads. ITV was meant to compete with the BBC. Many people were against the new broadcaster. While Clark's appointment made some feel better, others thought he was betraying artistic and intellectual standards.

Clark was not new to broadcasting. He had appeared on radio often since 1936. That year, he gave a radio talk about a Chinese Art exhibition. The next year, he made his television debut, showing Florentine paintings from the National Gallery. During the war, he was a regular on BBC radio's The Brains Trust. While leading the new ITA, he generally stayed off the air. He focused on keeping the new network going during its difficult early years. By the end of his three-year term as chairman, Clark was seen as a success. But privately, he thought there were too few high-quality programs on the network. Lew Grade, who ran one of the ITV channels, strongly felt that Clark should make his own art programs. As soon as Clark stepped down as chairman in 1957, he accepted Grade's invitation. His biographer, Stourton, says, "this was the true beginning of arguably his most successful career – as a presenter of the arts on television."

Becoming a TV Presenter: ITV (1957–1966)

Clark's first TV series for ATV, Is Art Necessary?, started in 1958. Both he and television were still figuring things out. Programs in the series ranged from stiff studio shows to a film where Clark and Henry Moore explored the British Museum at night with flashlights. When the series ended in 1959, Clark and the production team reviewed and improved their methods for the next series, Five Revolutionary Painters, which attracted many viewers.

By 1960, when he presented a program about Picasso, Clark had become even better at presenting. He seemed relaxed and knowledgeable. Two series on architecture followed. These ended with a program called The Royal Palaces of Britain in 1966. This was a joint project by ITV and the BBC. It was called "by far the most important heritage program shown on British television to date." The Guardian newspaper described Clark as "the perfect man for the job – scholarly, polite and gently funny." The Royal Palaces, unlike earlier shows, was filmed in color. But it was still shown in black and white, which bothered Clark. The BBC was planning to broadcast in color by this time. His new contact with the BBC for this film helped him eventually return to their shows. Before that, he stayed with ITV for a 1966 series, Three Faces of France. This series featured the works of Courbet, Manet, and Degas.

Civilisation: A Landmark Series (1966–1969)

David Attenborough, who managed the BBC's new second television channel, BBC2, was in charge of bringing color broadcasting to the UK. He had the idea for a series about great paintings to show off color television. He was sure that Clark would be the best presenter for it. Clark liked the idea but at first didn't want to commit. He later remembered that what convinced him was Attenborough's use of the word "civilisation" to describe what the series would be about.

The series had thirteen programs, each fifty minutes long. Clark wrote and presented them. They covered Western European civilization from the end of the Dark Ages to the early 20th century. Since the series didn't include ancient Greek, Roman, or Asian cultures, a title was chosen to show it wasn't everything: Civilisation: A Personal View by Kenneth Clark. Even though it focused mainly on visual arts and architecture, it also had big parts about drama, literature, philosophy, and social movements. Clark wanted to include more about law and philosophy, but he "could not think of any way of making them visually interesting."

After some initial disagreements, Clark and his main director, Michael Gill, developed a good working relationship. They and their team spent three years, starting in 1966, filming in 117 locations in 13 countries. The filming used the best technology of the time and quickly went over budget. It cost £500,000 by the time it was finished. Attenborough changed his broadcasting schedule to spread out the cost.

There were some complaints, then and later, that by focusing on traditional great artists (all men), Clark ignored women artists. Critics also said he presented "a story of famous names and beautiful objects with little thought for how money or politics shaped them." His way of working was called "the great man approach." He described himself on screen as someone who admired heroes and was a bit old-fashioned.

The broadcaster Huw Wheldon believed that Civilisation was "a truly great series, a major work... the first big project tried and completed on TV." Many critics, even those who didn't like Clark's choices, agreed that the filming set new standards. Civilisation had huge viewing numbers for a high art series: 2.5 million viewers in Britain and 5 million in the US. Clark's book that went with the series has always been in print. The BBC still sells thousands of DVD sets of Civilisation every year. In 2016, The New Yorker newspaper repeated what John Betjeman said, calling Clark "the man who made the best telly you’ve ever seen."

The British Film Institute notes how Civilisation changed cultural television. It set the standard for later documentary series, from Alastair Cooke's America (1972) and Jacob Bronowski's The Ascent of Man (1973) to today.

Later Years and Legacy

More TV and Books (1970–1983)

Clark made a series of six programs for ITV called Pioneers of Modern Painting. His son Colin directed them. They were shown in November and December 1971. Each program was about a different artist: Manet, Cezanne, Monet, Seurat, Rousseau, and Munch. Even though they were on commercial television, there were no ads during each program. With money from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC bought copies of the series. They shared them with colleges and universities across the US.

Five years later, Clark returned to the BBC. He presented five programs about Rembrandt. This series, also directed by Colin Clark, looked at different parts of Rembrandt's work, from his self-portraits to his Bible scenes. The National Gallery says about this series, "These art history lectures are a trusted study of Rembrandt and show examples of his work from over fifty museums."

Clark was the head of the University of York from 1967 to 1978. He was also a trustee of the British Museum. In his last ten years, he wrote thirteen books. Some were based on his research for his lectures and TV series. He also wrote two books about his life, Another Part of the Wood (1974) and The Other Half (1977). He was known for being a bit mysterious and hard to know throughout his life. This was shown in his two autobiography books. His biographer, Piper, described them as "beautifully and cleverly written, sometimes very touching, often very funny [but] somewhat distant, as if about someone else."

In his final years, Clark suffered from an illness that affected his arteries. He passed away at the age of 79 in a nursing home in Hythe, Kent, after a fall.

Family Life

In 1927, Clark married a fellow student named Elizabeth Winifred Martin, known as "Jane." They had three children: Alan in 1928, and twins Colette (called Celly) and Colin in 1932.

Outside of his official jobs, Clark enjoyed what he called "the Great Clark Boom" in the 1930s. He and his wife lived and entertained in a grand style in a large house in Portland Place. According to Piper, "the Clarks together became stars of London's high society, smart people, and fashion, from Mayfair to Windsor."

The Clarks' marriage was loving but sometimes difficult. Clark had relationships with other women. While Jane also had relationships, she took some of her husband's outside relationships badly. She had severe mood swings and later a stroke. Clark remained very supportive of his wife as her health declined. The Clarks' relationships with their three children were sometimes hard, especially with their older son, Alan. His father saw Alan as a strong supporter of fascism but also as the smartest in the family. Alan became a Conservative member of parliament and a junior minister. He was also known for his diaries. The younger son, Colin, became a filmmaker. He directed his father in television series in the 1970s. The twin daughter, Colette, became an official and board member of the Royal Opera House. She lived longer than her parents and brothers. She was the main source for James Stourton's official book about her father, published in 2016.

During the war, the Clarks lived in a cottage in Hampstead before moving to a much larger house nearby. In 1953, they moved when Clark bought the Norman castle of Saltwood in Kent. This became the family home. In his later years, he gave the castle to his older son and moved to a house built specifically for him on the castle grounds.

Jane Clark passed away in 1976. Her death was expected, but it left Clark heartbroken. Several of his female friends hoped to marry him. His closest female friend for thirty years was the photographer Janet Woods. She, along with Clark's daughter and sons, was upset when he said he planned to marry Nolwen de Janzé-Rice (1924–1989). The family felt that Clark was acting too quickly by marrying someone he hadn't known well for very long. But the wedding took place in November 1977. Clark and his second wife stayed together until he died.

His Beliefs

Clark's parents had Liberal views. Ruskin's social and political ideas influenced young Clark. Mary Beard wrote that Clark voted for the Labour party his whole life. His religious beliefs were unusual, but he believed in God and rejected atheism. He found the Church of England too focused on worldly things. Shortly before he died, he joined the Roman Catholic Church.

Awards and Recognition

Honors and Memorials

Clark received many state and other honors. These included being made a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath in 1938. He became a Fellow of the British Academy in 1949, a Companion of Honour in 1959, and a life peer in 1969. He was also made a Companion of Literature in 1974 and received the Order of Merit in 1976. Outside of Britain, he received honors from France, Finland, and Austria.

Clark was elected a member or honorary member of many art and academic groups around the world. These included groups in France, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the Swedish Academy, and the Florentine Academy. He received honorary degrees from many universities in the UK and the US, including Oxford and Columbia. He was also an honorary fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects and the Royal College of Art. Other awards included the Serena Medal for Italian Studies and the Gold Medal from New York University. Clark's old school, Winchester College, holds an annual art history speaking competition for the Kenneth Clark Prize. The winner receives a golden Lord Clark Medal. At the Courtauld Institute in London, the main lecture hall is named in Clark's honor.

His Reputation

In 2014, The Tate held an exhibition called "Kenneth Clark: Looking for Civilisation." It showed Clark's impact "as one of the most influential figures in British art of the 20th century." The exhibition used works from Clark's own collection and other sources. It looked at his roles as an art supporter and collector, art historian, public servant, and TV presenter. It showed how he "brought art in the 20th century to a more popular audience." The BBC called him "arguably the most influential figure in 20th century British art."

Clark knew that his traditional views on art would be disliked by some modern art critics. He was not surprised when younger critics, like John Berger, attacked him in the 1970s. Clark's reputation among critics today is higher for his books and TV series than for his consistency as a collector. At the time of the Tate exhibition in 2014, critic Richard Dorment said that Clark made many good purchases but also many mistakes. Besides the Previtali Scenes from Tebaldeo's Eclogues, Dorment listed works Clark wrongly thought were by Michelangelo, Pontormo, Elsheimer, and Claude. He also mentioned a Seurat and a Corot that were real but not good examples of the artists' work. Other critics agreed that Clark's most lasting achievements were as a writer and as someone who made art popular for many people.

Among his books is "the best introduction to the art of Leonardo da Vinci ever written." Piper highlights, in addition to the Leonardo book, Clark's Piero della Francesca (1951), The Nude (1956), and Rembrandt and the Italian Renaissance (1966).

Books by Kenneth Clark

|

|

See also

In Spanish: Kenneth Clark para niños

In Spanish: Kenneth Clark para niños

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |