Paul Nash (artist) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Paul Nash

|

|

|---|---|

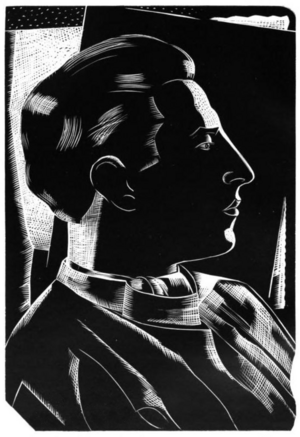

Nash in a woodcut self-portrait (1923)

|

|

| Born | 11 May 1889 Kensington, London, England

|

| Died | 11 July 1946 (aged 57) |

| Education |

|

| Known for | Painting, printmaking |

| Movement | Surrealism |

| Spouse(s) |

Margaret Theodosia Odeh (m. 1914–1946)

|

Paul Nash (born May 11, 1889 – died July 11, 1946) was a famous British painter. He was known for his surrealist art and for being a war artist. Nash also worked as a photographer, writer, and designer. He is considered one of the most important landscape artists of his time. Nash helped shape Modernism in English art.

Paul Nash was born in London. He grew up in Buckinghamshire and loved the countryside. He studied at the Slade School of Art. Nash was especially inspired by landscapes with old historical elements. These included ancient burial mounds and Iron Age hill forts like Wittenham Clumps. The standing stones at Avebury in Wiltshire also fascinated him.

His artworks from World War I are some of the most famous images of that conflict. After the war, Nash kept painting landscapes. At first, his style was formal and decorative. But in the 1930s, his art became more abstract and surreal. He often placed everyday objects in his landscapes. This gave them new meaning and symbolism.

During World War II, Nash was ill with asthma. This illness eventually led to his death. Even so, he created two series of paintings showing airplanes as if they were alive. He then painted many landscapes full of deep meaning. These works are very well-known from that period. Nash was also a talented book illustrator. He designed stage scenery, fabrics, and posters too. He was the older brother of artist John Nash.

Contents

Early Life and Art

Paul Nash was the son of William Harry Nash, a successful lawyer. His mother was Caroline Maude. He was born in Kensington and grew up in West London. In 1902, his family moved to Iver Heath in Buckinghamshire. They hoped the countryside would help his mother, who was very ill. His mother passed away in 1910.

Paul Nash was first meant to join the navy. But he failed the entrance exam. A friend, Eric Kennington, encouraged him to become an artist. Nash studied at the Chelsea College of Art and Design. Then he went to the London College of Communication. He spent two years there, writing poetry and plays. His work was noticed by Selwyn Image.

His friends told him to attend the Slade School of Art. He joined in 1910. The Slade School had many talented young artists at that time. These included Stanley Spencer and Christopher R. W. Nevinson. Nash found figure drawing difficult. He only stayed at the school for one year.

Nash had art shows in 1912 and 1913. He often showed his drawings and watercolors. These mostly featured moody landscapes. He was inspired by the poet William Blake and painters like Samuel Palmer. Two places were very important in his early landscape art. One was the view from his father's house in Iver Heath. The other was Wittenham Clumps, two hills with trees in the Thames Valley. These places would inspire Nash throughout his life. By 1914, Nash was becoming successful. He also worked briefly at the Omega Workshops. He was chosen to join The London Group in 1914.

World War I Experiences

Joining the Army

On September 10, 1914, World War I had just begun. Nash joined the army as a Private. He was part of the Artists' Rifles. His duties, like guarding the Tower of London, still allowed him time to draw.

In December 1914, Nash married Margaret Theodosia Odeh. She was an Oxford-educated activist for Women's Suffrage. They had no children.

Nash started officer training in August 1916. In February 1917, he was sent to the Western Front. He was a second lieutenant in the Hampshire Regiment. He was stationed at St. Eloi in the Ypres Salient. It was a relatively calm time there. Nash saw that the landscape was recovering from the war's damage.

On May 25, 1917, Nash fell into a trench and broke a rib. He was sent back to London by June 1. A few days later, most of his old unit were killed in a battle. Nash felt lucky to be alive. While recovering, he made twenty drawings about the war. These were based on his sketches from the Front. Most of these drawings showed the spring landscape. They were well-received when shown in June 1917.

Because of these exhibitions, Christopher Nevinson suggested Nash become an official war artist. Nash was preparing to return to France as a soldier. But then he learned his request to be a war artist was approved.

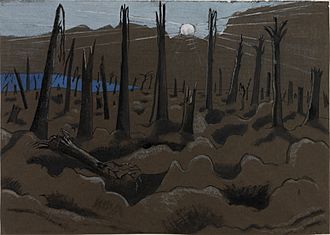

War Artist in Belgium, 1917

In November 1917, Nash went back to the Ypres Salient. He was a uniformed observer. The Third Battle of Ypres had been going on for three months. Nash often faced shellfire in Flanders. The winter landscape was very different from what he had seen in spring. The constant shelling had destroyed the drainage system. Months of rain had caused widespread flooding and deep mud.

Nash was very upset by this destruction of nature. He felt the land could no longer support life. He became angry and disappointed with the war. He wrote about this in letters to his wife. In one letter from November 16, 1917, he described the landscape as "the most frightful nightmare." He said it was "unspeakable, godless, hopeless." Nash felt he was "a messenger" to show people the terrible truth of the war.

Nash's anger fueled his creativity. He produced up to a dozen drawings a day. He took risks to get close to the front lines. He even extended his visit to work for the Canadians. He returned to England on December 7, 1917.

War Artist in England, 1918

In six weeks, Nash made "fifty drawings of muddy places." Back in England, he turned these into finished artworks. He worked hard for a solo show in May 1918. In Flanders, he mostly used pen-and-ink and watercolors. In England, he learned to make lithographs. His 1917 drawing Nightfall, Zillebecke District became the 1918 lithograph Rain. After the Battle shows a battlefield with bodies sinking into the mud. The Landscape – Hill 60 shows mud and shellholes under an exploding sky. One powerful new drawing was Wire. It showed a tree trunk wrapped in barbed wire. This represented the disaster of war.

In early 1918, Nash started painting with oils. His first oil painting was The Mule Track. It showed tiny soldiers trying to control pack animals during a bombardment. Using oils let Nash use more color. The explosions in The Mule Track have yellow, orange, and mustard shades. The Ypres Salient at Night shows the confusion of the trenches at night. This was made worse by constant shell explosions and flares.

While in France, Nash drew Sunrise, Inverness Copse. This drawing showed the aftermath of heavy fighting. It depicted a landscape of mud and blasted trees under a pale sun. In early 1918, Nash made a larger oil painting based on this drawing. Any hope the pale sun represented was gone. The new painting was called We are Making a New World. This title clearly mocked the war's goals. It showed a scene of total destruction. There are no people in the picture. The sun is a cold white circle. The clouds are blood red. One critic in 1994 called it like a "nuclear winter."

These new works were shown in Nash's exhibition, The Void of War. It was held at the Leicester Galleries in May 1918. Critics praised the show. They focused on how Nash showed nature as an innocent victim of the war.

'The Menin Road'

In April 1918, Nash was asked to paint a battlefield scene. This was for the British War Memorials Committee. He chose to paint a part of the Ypres Salient called 'Tower Hamlets'. This area was destroyed during the Battle of the Menin Road Ridge. Nash began painting the huge canvas, The Menin Road, in June 1918. It was almost 60 square feet in size. He finished it in February 1919. The painting shows a maze of flooded trenches and shell craters. Tree stumps point to a sky full of clouds and smoke. Two soldiers try to follow the road but seem trapped.

The 1920s: New Directions

After the war, Nash wanted to continue his art career. But he sometimes felt sad or down. He also worried about money. From 1919 to 1920, Nash lived in Buckinghamshire and London. He designed theatre sets for a play. Nash became well-known in the Society of Wood Engravers. He also taught part-time at the Cornmarket School of Art in Oxford.

Dymchurch and Iden

In 1921, Nash became very tired and upset from his war experiences. To help him recover, the Nashes moved to Dymchurch. They had visited there in 1919. In Dymchurch, he painted seascapes and the seawall. The seawall became a very important place in his art. The struggle between land and sea in these paintings reminded him of his war art. In 1922, Nash created Places, a book of seven wood engravings. He also started painting floral still-lifes. He continued his landscape paintings, like Chilterns under Snow (1923).

From 1924 to 1925, Nash taught at the Royal College of Art. His students included Eric Ravilious. In 1924, he had a successful exhibition. This allowed the Nashes to travel to France and Italy. Afterward, they moved to Iden near Rye. Iden and the Romney Marshes became the setting for many paintings. These included Winter Sea (1925). In 1927, Nash was elected to the London Artists' Association. He had another successful exhibition in 1928. This show was important because Nash began to explore abstraction in his work.

This change continued in 1929 and 1930. Nash created many new paintings:

- Landscape at Iden showed unrelated objects placed together. This was influenced by a 1928 exhibition by the surrealist Giorgio de Chirico.

- Northern Adventure and Nostalgic Landscape, St Pancras Station showed St Pancras Station through abstract shapes.

- Coronilla (1929) and Opening (1931) showed openings between spaces in an abstract way. Through them, trees or the sea could be seen.

- Nash finished Dead Spring in 1929 after his father died. It showed a dying plant surrounded by geometric shapes.

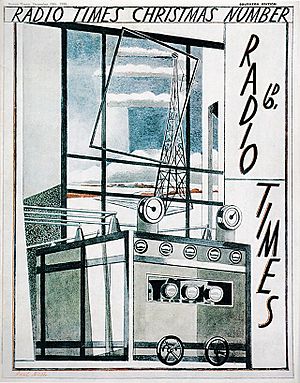

Other Art Forms

Nash often worked in other art forms besides painting. He created two books of his own wood engravings, Places and Genesis. In the 1920s, he also illustrated books for authors like Robert Graves. Nash designed the cover for Roads to Glory (1930), a book of World War I stories.

In 1921, Nash showed textile designs. In 1925, he created fabric designs for Modern Textiles. Later, in 1933, Brain & Co asked Nash to design for their Foley China range. In 1931, his wife Margaret gave him a camera. Nash became a keen photographer. He often used his own photos when painting.

By April 1928, Nash wanted to leave Iden. He did so after his father's death in 1929. He sold the family home and bought a house in Rye.

The 1930s: Surrealism and Ancient Sites

In 1930, Nash became an art critic for The Listener. He wrote about how Giorgio de Chirico and other modern artists influenced him. Nash became a leader of modernism in Britain. He promoted abstraction and surrealism in the 1930s. In 1933, he helped start Unit One. This was an important art group that included Henry Moore and Ben Nicholson. It aimed to bring new life to British art.

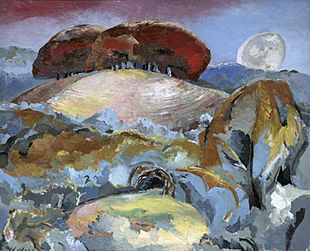

Avebury's Mystery

In 1931, Nash was asked to illustrate a book. He chose Sir Thomas Browne's Hydriotaphia, Urn Burial. He created 30 illustrations for the book. He also made larger watercolors and oil paintings about death and burial. These themes became important to Nash. In July 1933, he visited Silbury Hill and Avebury for the first time. This ancient landscape, with its neolithic monuments and standing stones, "excited and fascinated" him.

Nash painted Avebury many times in different styles. His 1934 paintings, Druid Landscape and Landscape of the Megaliths, are famous. The 1935 painting Equivalents for the Megaliths showed the site in an abstract way. Nash seemed to prefer the wilder look of Avebury before restoration work began in 1934.

Nash's father-in-law died in 1932. Nash wanted to move to Wiltshire. Instead, he moved to London in 1933. Then he and Margaret traveled to France, Gibraltar, and North Africa. When they returned in 1934, they rented a cottage near Swanage in Dorset. The poet John Betjeman asked Nash to write a book for the Shell Guides series. Nash agreed and wrote a guide to Dorset.

Swanage and Surrealism

From 1934 to 1936, Nash lived near Swanage in Dorset. He hoped the sea air would help his asthma. He worked on the Shell Guide to Dorset. He made many paintings and photographs during this time. Some were used in the guide book. The guide was published in 1935. Nash found Swanage to have a Surrealist quality. He wrote that it was like "a dream image where things are so often incongruous."

In Swanage, Nash met artist Eileen Agar. They worked together on several art pieces. Nash created notable surrealist works there. These included Events on the Downs, showing a giant tennis ball and a tree trunk. Another was Landscape from a Dream, with a hawk and a mirror. For a photo collage called Swanage, Nash showed objects found in Dorset. He placed them in a surreal landscape. On Romany Marsh, Nash found his first surrealist object. This piece of wood looked like a sculpture to him. It was shown at the first International Surrealist Exhibition in 1936.

By the time of the exhibition, Nash disliked Swanage. In mid-1936, he moved to Hampstead. There he wrote articles about "seaside surrealism." He made collages and assemblages. He also started his autobiography. In April 1937, he had a large solo show. That summer, he visited the Uffington White Horse. Soon after, he began Landscape from a Dream. In 1939, when World War II started, the Nashes moved to Oxford.

World War Two Art

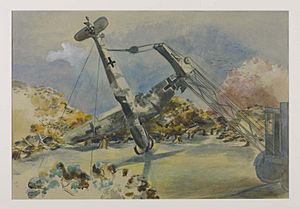

At the start of World War Two, Nash became a full-time war artist. He worked for the Royal Air Force. The Air Ministry was not always happy with his modern art. They wanted portraits of pilots. While working for them, Nash made two watercolor series. These were Raiders and Aerial Creatures. Raiders showed crashed German aircraft in English landscapes. Titles included Bomber in the Corn. The Air Ministry liked these patriotic works.

However, the Aerial Creatures series showed British aircraft as if they were alive. The Air Ministry disliked this so much that Nash's full-time contract ended in December 1940. But the War Artists' Advisory Committee still wanted his work. In January 1941, they agreed to buy paintings from him about air conflict. Nash worked on these until 1944. His first two were Totes Meer (Dead Sea) and Battle of Britain.

Totes Meer (Dead Sea) was submitted in 1941. It shows a "dead sea" of wrecked German plane parts. Nash based it on sketches and photos from a recovery unit. He only painted German planes. He wanted to show the fate of the "flying creatures which invaded these shores." He even made a postcard of the painting with Hitler's head on the wreckage. Kenneth Clark, head of the committee, called it "the best war picture so far." It is still a famous British painting of World War II.

Battle of Britain (1941) shows an air battle over land and sea. The white trails of Allied planes look like growing buds and petals. They seem to rise from the land. This is different from the rigid lines of the enemy planes. Clark saw the deep meaning in the work. He said Nash had found a new way to paint important events.

After Battle of Britain, Nash felt stuck creatively. He was also sick with asthma again. He made photo collages with symbols from his past works. He tried to get the Ministry of Information to use them as propaganda. But they refused. When he started painting again, he made Defence of Albion. This painting shows a Short Sunderland flying boat. Nash had trouble finishing it. He had only seen photos of the plane.

Nash's last painting for the committee was Battle of Germany. It was an imagined scene of a city being bombed. Nash used an abstract style. He explained it showed a city under attack. There was a pillar of smoke from burning buildings. White parachutes descended in the foreground. The smoke and moon were as threatening as the bombers. Kenneth Clark found the painting hard to understand. But he thought it might show what art could become after the war.

Final Works and Legacy

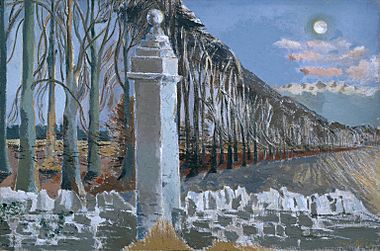

From 1942, Nash often visited artist Hilda Harrisson. He would recover there after his illnesses. From her garden, Nash could see the Wittenham Clumps. He had first visited them as a child. He painted them before World War I and again in the 1930s. Now, he painted a series of imaginative works of the Clumps under different phases of the Moon. Paintings like Landscape of the Vernal Equinox (1943) showed a mystical landscape. It was full of symbols of changing seasons and new life. Another inspiring place for Nash was Ascott. There he completed Pillar and Moon (1942). This painting explored the "mystical association of two objects."

Finishing Battle of Germany in September 1944 ended Nash's public work. He spent his last eighteen months quietly. In these months, Nash created a series of paintings called 'Aerial Flowers'. These included Flight of the Magnolia (1944). They combined his love of flying with his admiration for Samuel Palmer's art. Nash also returned to the influence of William Blake. This had affected his early art. He painted giant sunflowers, like Sunflower and Sun (1942). These were based on Blake's 1794 poem "Ah! Sun-flower".

Death

In his last ten days, Nash visited Dorset again. He saw Swanage and Corfe. Paul Nash died in his sleep from heart failure on July 11, 1946. This was due to his long-term asthma. He was buried on July 17, in the churchyard of St Mary the Virgin, Langley. An Egyptian stone carving of a hawk was placed on his grave. This was the same hawk he painted in Landscape from a Dream. A memorial exhibition for Nash was held at the Tate Gallery in March 1948. His wife Margaret died in 1960. They are buried together.

Legacy and Public Works

Paul Nash's artworks are in many collections. These include the Imperial War Museum and the Tate Gallery. In 1980, a complete list of his works was published. In 2016, artist Dave McKean published Black Dog: The Dreams of Paul Nash. This was a graphic novel about Nash's life and art.

A major exhibition of his work, 'Paul Nash', was held at Tate Britain in London. It ran from October 2016 to March 2017. Then it moved to the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts in Norwich.

See also

In Spanish: Paul Nash para niños

In Spanish: Paul Nash para niños

- Category:Paintings by Paul Nash

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |