Giovanni da Pian del Carpine facts for kids

Giovanni da Pian del Carpine (born around 1185 – died August 1, 1252) was an important Italian diplomat, church leader, and explorer. He was one of the first Europeans to visit the court of the Great Khan of the Mongol Empire. He wrote one of the earliest and most important Western descriptions of northern and central Asia, Rus, and other areas ruled by the Mongols. From 1247 to 1252, he was the head of the church in Serbia, based in Antivari.

Contents

Early Life and Church Work

Giovanni was likely from Umbria, a region in central Italy. His last name came from Pian del Carpine, which means "Hornbeam Plain." This area is now known as Magione, located between Perugia and Cortona. He was a close friend and student of Francis of Assisi, who founded the Franciscan order.

Giovanni was highly respected within the Franciscan order. He played a big part in spreading its teachings across northern Europe. He held important positions, serving as a warden in Saxony and a provincial leader in Germany. He might have also worked in Barbary and Cologne, and possibly been a provincial leader in Spain.

Why He Traveled to the Mongols

Giovanni was the provincial leader of Germany when the Mongols launched a huge invasion of eastern Europe. This included the Battle of Legnica on April 9, 1241. European forces were defeated at Legnica. This defeat almost led to Ögedei, the Khan of the Mongol Empire, taking control of most of Eastern Europe.

Even four years later, in Europe, people were still very afraid of the "Tatars" (Mongols). Because of this fear, Pope Innocent IV decided to send the first official Catholic mission to the Mongols. The missionaries were sent for two main reasons. First, to protest the Mongol invasion of Christendom. Second, to gather information about the Khan's plans and how strong his army was.

Giovanni's Great Journey

Pope Innocent IV chose Giovanni to lead this important mission. Giovanni seemed to be in charge of almost everything. As a papal legate (a special representative of the Pope), he carried a letter from the Pope to the Great Khan, called Cum non solum.

Giovanni started his journey from Lyon on Easter day, April 16, 1245. He was 63 years old. Another friar, Stephen of Bohemia, traveled with him. However, Stephen became too sick at Kaniv near Kyiv and had to stay behind. Giovanni then met with an old friend, Wenceslaus, the king of Bohemia. In Wrocław, another Franciscan, Benedykt Polak, joined them to act as an interpreter.

The Long Road to the Khan

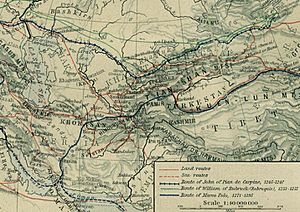

Their route took them through Kiev. They entered Mongol territory at Kaniv. Then they traveled across the Nepere and on to the Don and Volga rivers. Giovanni was the first Westerner to record the modern names for these rivers.

On the Volga River, they found the Ordu, which was the camp of Batu. Batu was a famous conqueror of eastern Europe and the top Mongol commander on the western borders of the empire. He was one of the most important princes from the family of Genghis Khan. Here, Giovanni and his companions, along with their gifts, had to walk between two fires. This was a Mongol custom to remove any bad thoughts or poisons. After this, they were presented to Prince Batu in early April 1246.

Batu ordered them to continue their journey to the court of the supreme Khan in Mongolia. On Easter day again, April 8, 1246, they began the second and hardest part of their trip. Giovanni wrote that they were "so ill that we could scarcely sit a horse." He also mentioned that during Lent, they had only eaten millet with salt and water, and drank snow melted in a kettle. They tightly bandaged their bodies to help them endure the extreme tiredness of this huge ride.

They crossed the Jaec or Ural River. They traveled north of the Caspian Sea and the Aral Sea to the Jaxartes or Syr Darya river. This was a "big river whose name we do not know," with Muslim cities on its banks. They then went along the shores of the Dzungarian lakes. Finally, on July 22 (the feast of St Mary Magdalene), they reached the imperial camp called Sira Orda, or Yellow Pavilion. This camp was near Karakorum and the Orkhon River. Giovanni and his friends rode an estimated 3,000 miles in just 106 days!

Meeting the Great Khan

At this time, the Mongol Empire was without a ruler because Ögedei Khan had died. Güyük, Ögedei's oldest son, was chosen to be the next emperor. His official election happened in a great Kurultai, which was a large meeting of the tribes. This took place while the friars were at Sira Orda. Between 3,000 and 4,000 envoys and representatives from all over Asia and eastern Europe gathered, bringing gifts and showing respect.

On August 24, Giovanni and his companions watched the official crowning of the new emperor. This happened at another camp nearby called the Golden Ordu. After the ceremony, they were presented to the new emperor, Güyük.

The Great Khan, Güyük, refused the Pope's invitation for him to become Christian. Instead, he demanded that the Pope and the rulers of Europe should come to him and promise their loyalty. The Khan did not let the expedition leave until November. He gave them a letter for the Pope. This letter was written in Mongol, Arabic, and Latin. It was a short, powerful statement from the Khan, claiming his role as God's punishment.

The Journey Home

Giovanni and his companions began their long winter journey home. Often, they had to sleep on the bare snow, or on ground they had scraped clear of snow with their feet. They finally reached Kiev on June 10, 1247. There, and during the rest of their journey, the Christian people of the Slavic lands welcomed them. They were treated with great hospitality, as if they had returned from the dead.

After crossing the Rhine River at Cologne, they found the Pope still in Lyon. They delivered their report and the Khan's letter to him.

Not long after, Giovanni was rewarded for his hard work. He was made the archbishop of Primate of Serbia in Antivari in Dalmatia. He was also sent as a special representative to Louis IX of France. Giovanni lived only five more years after the difficult journey. He died on August 1, 1252.

His Important Book

Giovanni da Pian del Carpine wrote a report about his trip to the Mongol Empire called Ystoria Mongalorum. He finished it in the 1240s. It is the oldest European account of the Mongols. Carpine was the first European to try and write down the history of the Mongols. Two versions of the Ystoria Mongalorum are known to exist: Carpine's own version and another one, often called the Tartar Relation.

Erik Hildinger later translated Giovanni's book into English.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Giovanni da Pian del Carpine para niños

In Spanish: Giovanni da Pian del Carpine para niños