Compass facts for kids

A compass is a tool that helps you find your way around. It shows you directions like north, south, east, and west. These are called "cardinal directions." Most compasses have a picture called a compass rose that shows these directions with letters like N, S, E, and W.

People in China first invented the magnetic compass during the Han Dynasty (around 206 BC). They first used it for telling the future! Later, during the 11th century, the Chinese started using it for navigation, which means finding their way. People in Western Europe and the Islamic world started using compasses around the early 1200s.

When you use a compass, you line up the "N" (North) on the compass with the real north direction. Compasses often also show angles in degrees. North is 0 degrees. The angles go up as you move clockwise. So, east is 90 degrees, south is 180 degrees, and west is 270 degrees. These numbers help you find specific azimuths or bearings.

Contents

How a Magnetic Compass Works

The magnetic compass is the most common type. It has a special needle that points to "magnetic north." This is because the needle is magnetized and lines up with the Earth's magnetic field. The Earth's magnetic field pulls the north end of the needle towards the North Magnetic Pole, and the other end towards the South Magnetic Pole.

The needle sits on a very smooth pivot point, often a jewel bearing, so it can spin easily. When you hold the compass flat, the needle turns until it settles and points in the right direction.

When you look at maps, directions are usually shown based on true north. This is the direction to the real North Pole, which is where the Earth's axis spins. The angle between true north and magnetic north is called magnetic declination. This angle changes depending on where you are on Earth. Most maps show you the local magnetic declination. This helps you line up your map with true north using your compass. The Earth's magnetic poles move slowly over time, so it's good to use a map with the most recent information. Some compasses can even be adjusted to show true directions directly.

History of Compasses

The very first compasses in ancient Han dynasty China were made from lodestone. This is a natural rock that is already magnetized. Later, people made compasses from iron needles. They would magnetize these needles by rubbing them with a lodestone.

Around the year 1300, "dry compasses" started appearing in Medieval Europe and the Islamic world. These were compasses where the needle wasn't in liquid. In the early 1900s, liquid-filled magnetic compasses became popular.

Modern Compasses

Magnetic Compasses Today

Most modern compasses have a magnetized needle or a spinning dial inside a capsule. This capsule is completely filled with a liquid, like lamp oil or mineral oil. The liquid helps the needle stop moving quickly, making it more stable and easier to read.

Many modern compasses have a clear baseplate and a protractor tool. These are often called "orienteering" or "map compasses." They have a separate magnetized needle inside a spinning capsule. There's also an "orienting box" to help you line up the needle with magnetic north. The clear base has lines to help you line up the compass with a map. An outer dial (bezel) shows degrees. The baseplate also has a "direction-of-travel" (DOT) arrow. This helps you take bearings directly from a map.

Some modern compasses also have map scales to measure distances. They might have glowing marks for night use or special sights (like mirrors) for more accurate readings of faraway objects. Some have "global" needles that work in different parts of the world. Others can be adjusted for magnetic declination, so you can get true directions right away.

Some military forces, like the U.S. Army, use field compasses with magnetic dials instead of needles. These often have a special sight (lensatic or prismatic) that lets you read the bearing while aiming the compass at an object. These types of compasses usually need a separate tool to take bearings from a map.

Some military compasses use a special material called tritium to make them glow in the dark. This light doesn't need sunlight or other light to "recharge." However, tritium's glow fades over about 12 years.

Compasses used on ships often have two or more magnets attached to a compass card. This card spins freely. A "lubber line" on the compass shows the ship's direction. Old compasses used 32 "points," but modern ones use degrees. The compass is usually in a special box called a binnacle that keeps it level even when the ship moves.

Thumb Compasses

A thumb compass is a type of compass often used in orienteering. This is a sport where reading maps and understanding the land are very important. Thumb compasses usually have few or no degree markings. They are mainly used to line up a map with magnetic north. Many thumb compasses are also transparent. This lets you hold the compass and a map in one hand and see the map through the compass.

Gyrocompasses

A gyrocompass is a non-magnetic compass. It finds true north using a fast-spinning wheel and the Earth's rotation. Gyrocompasses are commonly used on ships. They have two main benefits over magnetic compasses:

- They find true north, not magnetic north.

- They are not affected by metal like iron or steel in a ship.

Large ships usually use a gyrocompass, keeping a magnetic compass as a backup. Smaller boats often use electronic fluxgate compasses. Magnetic compasses are still popular because they are small, simple, cheap, and don't need power. They also work even if electronic signals are blocked.

Electronic Compasses

Small compasses found in smartwatches, mobile phones, and other gadgets are electronic compasses. They use tiny magnetic field sensors that send data to a computer chip. This chip figures out the device's direction. These sensors are very precise and measure the Earth's magnetic field.

GPS Receivers as Compasses

GPS receivers can also act like compasses. If a GPS receiver has two or more antennas and is combined with an inertial motion unit (IMU), it can figure out direction very accurately. These devices find the exact location of the antennas on Earth, and from that, they can calculate the cardinal directions. They are mostly used for boats and airplanes.

Small, portable GPS receivers with just one antenna can also find directions if they are moving. By tracking their position over a few seconds, they can calculate their speed and the true direction they are moving. This is helpful for knowing where a vehicle is actually going, especially if there's wind or current pushing it.

GPS compasses are like gyrocompasses because they find true North and are not affected by magnetic fields. They are also cheaper than gyrocompasses and work better near the poles. However, they rely on GPS satellites, which can be affected by electronic attacks or solar storms. Gyrocompasses are still used for military purposes, especially in submarines where other compasses don't work. But for everyday use, GPS compasses are becoming more common, with magnetic compasses as backups.

Special Compasses

Besides regular navigation compasses, there are special compasses for specific jobs:

- The Qibla compass helps Muslims find the direction to Mecca for prayers.

- Optical or prismatic hand-bearing compasses are used by surveyors, cave explorers, and geologists. These are very accurate and often have built-in lights.

- Trough compasses were used for land surveying many centuries ago. They were long and narrow.

What Can Limit a Magnetic Compass?

Magnetic compasses work very well in most places. But near the Earth's magnetic poles, they become hard to use. As you get closer to a magnetic pole, the difference between true north and magnetic north (magnetic declination) gets much bigger. At some point, the compass might not point in any clear direction. Also, the needle can start to tilt up or down near the poles. This is called "magnetic inclination." Cheap compasses might get stuck because of this, giving wrong readings.

Magnetic compasses are also affected by other magnetic fields. Things like magnetic rocks, large iron or steel objects, electric motors, or strong magnets can make a compass give wrong readings. Any wire with electricity flowing through it also creates a magnetic field. Some compasses have small magnets that can be adjusted to help fix these errors.

A compass can also make mistakes when you speed up or slow down in a car or plane. Depending on where you are on Earth and if you are speeding up or slowing down, the compass might show a slightly different direction.

Another error happens when you turn. If you turn from east or west, the compass needle might lag behind or jump ahead of your turn. Other tools like magnetometers or gyrocompasses are more stable in these situations.

How a Magnetic Compass is Made

Magnetic Needle

To make a compass, you need a magnetic rod, often called a magnetic needle. You can make one by lining up an iron or steel rod with the Earth's magnetic field and then hitting it. But this makes a weak magnet. A better way is to rub an iron rod repeatedly with a lodestone or another magnet. This magnetized rod is then placed on a very smooth surface so it can spin freely and line up with the magnetic field. One end is marked, usually the north-pointing end, so you know which way is north.

Needle-and-Bowl Compass

If you rub a needle on a lodestone, it becomes magnetized. If you then stick it into a cork or a piece of wood and float it in a bowl of water, it becomes a compass! People used these simple compasses for a long time until the "dry" compass with a spinning needle was invented around 1300.

Compass Points

At first, many compasses only showed magnetic north or the four main directions (north, south, east, west). Later, people divided the compass into more points. In China, they used 24 points, and in Europe, they used 32 equally spaced points.

Today, most compasses use a 360-degree system. North is 0 degrees, and the numbers go up clockwise all the way to 360. Some European countries in the 1800s used a "grad" system, where a right angle was 100 grads, making a full circle 400 grads.

Most military forces use a "millieme" system. This divides the compass dial into 6400 units or "mils." This gives them very precise measurements for things like aiming artillery.

Compass Balancing (Magnetic Dip)

The Earth's magnetic field changes in strength and angle at different places. Because of this, compasses are often balanced when they are made. This keeps the needle level and stops it from dragging, which could give wrong readings. Most compasses are balanced for one of five zones around the world. This balancing stops one end of the needle from dipping too much, which can make the compass stick.

Some compasses have a special needle system that works accurately no matter where you are. Other magnetic compasses have a small sliding weight on the needle itself. This weight, called a 'rider', can be moved to balance the needle if the compass is taken to a different magnetic zone.

Compass Correction

Like any magnetic tool, compasses are affected by nearby metal objects (like iron) and strong electrical forces. When you use a compass for hiking, keep it away from metal objects or electrical systems (like car engines). These can make the compass inaccurate. Compasses are especially tricky to use accurately in or near trucks or cars, even if they have built-in magnets to correct for errors.

On a ship, a compass must be corrected for errors caused by the iron and steel in the ship itself. This error is called deviation. Sailors "swing" the ship, turning it around a fixed point while noting its direction compared to fixed points on shore. They then create a "compass deviation card." This card helps the navigator change between the compass reading and the true magnetic direction. Compasses can be corrected by adjusting the "lubber line" (the line that shows the ship's direction) and by adding small magnets inside the compass case. The effect of magnetic materials in the ship can be corrected by placing two iron balls on either side of the compass.

A similar process is used to set up compasses in small airplanes. The compass deviation card is often placed near the compass on the control panel. Electronic compasses can even correct themselves automatically.

Using a Magnetic Compass

A magnetic compass points to the magnetic north pole, which is about 1,000 miles away from the true geographic North Pole. To find true North, you first find magnetic north and then adjust for "variation" and "deviation." Variation is the angle between true north and magnetic north. Maps often show this variation. Deviation is how the compass reacts to local magnetic fields from iron or electricity. You can partly fix this by placing the compass carefully and using small magnets. Sailors have known for a long time that these fixes don't completely remove all errors. So, they would measure the compass direction of a known landmark and then create correction tables.

Sailors need very accurate measurements. But for everyday use, you don't always need to worry about the small differences between magnetic and true North. Unless the magnetic declination is very large (20 degrees or more), a compass is usually good enough for short distances, especially on flat land with good visibility. By carefully tracking distances and magnetic directions, you can follow a path and even return to your starting point using only the compass.

Using a compass with a map (called terrain association) needs a different method. To find a "true bearing" (a direction based on true north) to a place on a map using a protractor compass, you place the edge of the compass on the map. Line it up so it connects your current spot with where you want to go. Then, you turn the orienting lines on the compass dial to line up with the true north lines on the map (like the vertical lines of longitude). Ignore the compass needle for now. The number on the compass at the direction-of-travel (DOT) line is your "true bearing" or map bearing. You can then follow this as your path to the destination. If you want a "magnetic" north bearing, you need to adjust the compass for the magnetic declination before you start, so the map and compass agree. Some compasses let you set this adjustment directly.

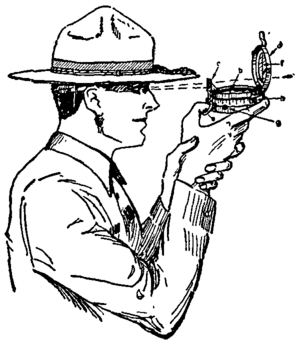

The modern hand-held protractor compass always has a direction-of-travel (DOT) arrow on its baseplate. To check if you are on the right path, or to make sure an object you see is your destination, you can take a new compass reading to that object (like the mountain in the picture). Point the DOT arrow on the baseplate at the object. Then, turn the compass until the needle lines up with the orienting arrow inside the capsule. The number shown is the magnetic bearing to the object. Again, if you are using "true" bearings, and your compass isn't already adjusted for declination, you need to add or subtract the magnetic declination to change the magnetic bearing into a true bearing. The exact magnetic declination changes depending on where you are and over time, but it's often shown on the map or can be found online. If you've been following the correct path, your compass's corrected bearing should match the true bearing you got from the map.

A compass should be placed on a flat surface. This lets the needle spin freely on its pivot. If the compass is tilted, the needle might touch the casing and not point accurately. To check if the needle is level, look closely and tilt the compass slightly. See if the needle swings freely without touching the sides. If it tilts to one side, gently tilt the compass the other way until the needle is flat.

Avoid using compasses near magnets or any electronics. Magnetic fields from electronics can easily mess up the needle, stopping it from lining up with the Earth's magnetic field. The Earth's natural magnetic forces are quite weak. Magnetic fields from household electronics can be much stronger and overpower the compass needle. Being near strong magnets can even make the compass needle's poles change or reverse!

Also, avoid areas with lots of iron, like certain rocks that contain magnetic minerals such as Magnetite. These rocks might look dark and metallic. To see if a rock or an area is causing problems for your compass, move away from it and see if the needle moves. If it does, that area or rock is causing interference and you should avoid it.

Images for kids

-

A figurine of a man holding a compass from the Song Dynasty

See also

In Spanish: Brújula para niños

In Spanish: Brújula para niños

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |