Otto the Great facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Otto the Great |

|

|---|---|

Depiction of Otto on his seal in 968

|

|

| Holy Roman Emperor | |

| Reign | 2 February 962 – 7 May 973 |

| Coronation | 2 February 962 Rome |

| Predecessor | Berengar I |

| Successor | Otto II |

| King of Italy | |

| Reign | 25 December 961 – 7 May 973 |

| Coronation | 10 October 951 Pavia |

| Predecessor | Berengar II |

| Successor | Otto II |

| King of East Francia (Kingdom of Germany) | |

| Reign | 2 July 936 – 7 May 973 |

| Coronation | 7 August 936 Aachen Cathedral |

| Predecessor | Henry the Fowler |

| Successor | Otto II |

| Duke of Saxony | |

| Reign | 2 July 936 – 7 May 973 |

| Predecessor | Henry the Fowler |

| Successor | Bernard I |

| Born | 23 November 912 possibly Wallhausen, East Francia |

| Died | 7 May 973 (aged 60) Memleben, Holy Roman Empire |

| Burial | Magdeburg Cathedral |

| Spouse | Eadgyth of England (930–946) Adelaide of Italy (951–973) |

| Issue |

|

| Dynasty | Ottonian |

| Father | Henry the Fowler |

| Mother | Matilda of Ringelheim |

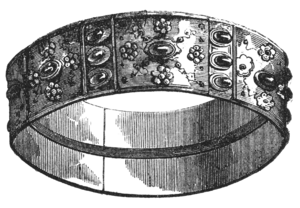

| Signum manus |  |

Otto I (born November 23, 912 – died May 7, 973), also known as Otto the Great, was a powerful king and emperor. He ruled the East Frankish Kingdom (which later became Germany) from 936. In 962, he became the Holy Roman Emperor, a title he held until his death in 973.

Otto was the oldest son of Henry the Fowler and Matilda of Ringelheim. When his father died in 936, Otto became the Duke of Saxony and King of the Germans. He worked hard to unite all the German tribes into one strong kingdom. He also made the king's power much stronger, reducing the power of the local nobles. Otto placed his family members in important positions. This made the dukes, who used to be almost as powerful as the king, become loyal subjects under his rule. He also changed the Church in Germany to help strengthen his royal authority.

After stopping a short civil war, Otto famously defeated the Magyars at the Battle of Lechfeld in 955. This victory ended the Hungarian invasions of Western Europe. Because he defeated the pagan Magyars, Otto was seen as a hero who saved Christendom. This helped him keep a strong hold on his kingdom. By 961, Otto had also conquered the Kingdom of Italy. Following the example of Charlemagne, Otto was crowned emperor in 962 by Pope John XII in Rome.

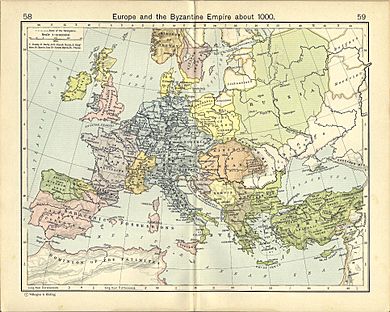

Otto's later years involved some disagreements with the Pope. He also worked to keep control over Italy. While ruling from Rome, Otto tried to improve relations with the Byzantine Empire. They were not happy about his claim to be emperor and his expansion into southern Italy. To solve this, the Byzantine princess Theophanu married his son Otto II in April 972. Otto returned to Germany in August 972 and died in May 973. His son, Otto II, became the next emperor.

Historians see Otto as a very successful ruler and a great military leader. He helped create a strong empire. He also supported a time of renewed art and learning called the "Ottonian Renaissance."

Contents

Otto's Early Life and Family

Otto was born on November 23, 912. His father was Henry the Fowler, the Duke of Saxony. His mother was Matilda of Ringelheim. Henry had another son, Thankmar, from an earlier marriage. Otto had four younger siblings: Hedwig, Gerberga, Henry, and Bruno.

How Henry Became King

On December 23, 918, Conrad I of Germany, the King of East Francia, died. Conrad asked his brother, Eberhard, to offer the crown to Otto's father, Henry. Even though Conrad and Henry had disagreed before, Henry had not openly fought the king since 915. Conrad had also struggled with other German dukes, which weakened his power.

After a few months, Henry was chosen as king by the nobles in May 919. This was the first time a Saxon, not a Frank, ruled the kingdom. Most dukes accepted Henry, but Arnulf, Duke of Bavaria did not at first. Henry defeated Arnulf in battle and forced him to accept his rule.

Otto's Path to Power

Otto first gained military experience fighting against the Wendish tribes on Germany's eastern border. In 929, his son William, who later became Archbishop of Mainz, was born.

By 929, Henry had secured his power. He likely started preparing Otto to take over the kingdom. Around this time, Otto was first called "king" in a document.

Henry also arranged an alliance with Anglo-Saxon England. He wanted to find a bride for Otto from a royal family. This would make Henry's rule more legitimate and strengthen ties between the two Saxon kingdoms. King Æthelstan of England sent two of his half-sisters. Henry chose Eadgyth for Otto, and they married in 930.

Before Henry died, a meeting of nobles in Erfurt formally approved Otto as the only heir. This was different from the usual custom where all sons would get a part of the kingdom.

Otto Becomes King

His Coronation Day

Henry died on July 2, 936, from a stroke. He was buried at Quedlinburg Abbey. At this time, all the German tribes were united. Otto, almost 24, became Duke of Saxony and King of Germany. His coronation was on August 7, 936, in Aachen, the old capital of Charlemagne. Otto wore Frankish clothes to show he was the true successor to Charlemagne.

At the coronation banquet, the four other dukes of the kingdom served Otto. This showed they accepted him as their new king.

However, Otto's family was not completely peaceful. His younger brother, Henry, also wanted the throne. Their mother, Matilda, had even preferred Henry. Otto also faced opposition from local nobles. He appointed new leaders, which angered some who felt they had a better claim.

Rebellions Against Otto

In 937, Arnulf, Duke of Bavaria died, and his son Eberhard became duke. Eberhard refused to accept Otto's authority. Otto defeated him in two battles in 938 and sent him away. Otto then appointed Eberhard's uncle, Berthold, as the new Duke of Bavaria. Berthold agreed to let Otto choose bishops and manage royal property in Bavaria.

Around the same time, Otto settled a dispute between a Saxon noble and Duke Eberhard of Franconia. Otto made Eberhard pay a fine and punished his officers in a very shameful way. This angered Eberhard, who then joined Otto's half-brother Thankmar and others in a rebellion in 938. Otto quickly put down the revolt. Thankmar was killed, and Eberhard and Archbishop Frederick were pardoned after a short exile.

Soon after, Eberhard planned another rebellion. He promised to help Otto's brother Henry become king. Gilbert, Duke of Lorraine, also joined. Otto sent Henry away, and Henry fled to King Louis IV of France. Louis joined the rebels, hoping to regain control of Lorraine. Otto allied with Louis's rival, Hugh the Great.

Otto's forces won some battles. In October 939, Otto's allies surprised Eberhard and Gilbert at the Battle of Andernach. Eberhard was killed, and Gilbert drowned. Henry then surrendered to Otto, ending the rebellion. Otto took direct control of Franconia. He also made peace with Louis IV, who recognized Otto's rule over Lorraine. Otto's sister Gerberga, Gilbert's widow, married Louis IV.

In 940, Otto and Henry made peace. Henry returned to East Francia, and Otto made him the new Duke of Lorraine. But Henry still wanted the German throne. In 941, he plotted with Archbishop Frederick to kill Otto. Otto found out and arrested them. He later pardoned them after they publicly showed their regret.

Strengthening His Power

From 941 to 951, Otto had firm control. He made decisions without needing the nobles' approval. He chose people for important jobs based on their loyalty to him, not their family background. This was a big change from how things used to be. Otto's mother, Matilda, disagreed with this. She was briefly sent away in 947 but returned at his wife Eadgyth's request.

Nobles found it hard to get used to Otto's style. Traditionally, all sons of a king would get a part of the kingdom. But Otto's father had chosen Otto to rule a united kingdom. Otto was different from his father, Henry, who saw himself as "first among equals." Otto believed he had a "divine right" to rule. He treated his kingdom as a feudal monarchy, where he was the ultimate authority.

Otto's new approach made him the undisputed master. Nobles who rebelled had to publicly admit their guilt and surrender. Otto usually gave them mild punishments and often restored them to power. His brother Henry rebelled twice and was pardoned both times. He even became Duke of Bavaria. However, commoners who rebelled were treated much more harshly, often executed.

Otto rewarded loyal supporters. He used family ties to strengthen his rule. His daughter Liutgarde married Conrad the Red, who became Duke of Lorraine in 944. In 947, Otto's son Liudolf married Ida, the daughter of Duke Herman I of Swabia. This helped Liudolf become Duke of Swabia in 950. In 948, Otto made his brother Henry the Duke of Bavaria. This finally brought peace between the brothers.

On January 29, 946, Otto's wife Eadgyth died at age 35. Otto buried her in Magdeburg Cathedral. They had two children. Otto then started planning for his succession. He wanted his son Liudolf to be the sole ruler after him. Otto made all the important leaders swear loyalty to Liudolf.

Otto's Foreign Relations

France

Kings in West Francia (France) had lost power to their nobles. They still claimed Lorraine, a territory also claimed by Otto. Otto supported Louis IV's rival, Hugh the Great. Louis IV tried to take Lorraine in 940, claiming it through his marriage to Otto's sister Gerberga. But Otto did not accept this and made his brother Henry the duke instead.

Otto helped make peace between Louis IV and Hugh in 942. As part of the deal, Louis IV gave up his claims to Lorraine. In 946, Louis IV was captured by Normans. Otto invaded France to help Louis IV, but his army was not strong enough to capture key cities. He did manage to restore Artald as Archbishop of Reims.

In 948, Otto called a meeting of bishops at Ingelheim. This showed his strong power in both East and West Francia. The meeting confirmed Artald as Archbishop of Reims. Hugh finally accepted Louis IV as king in 950.

Burgundy

Otto continued the peaceful relationship with the Kingdom of Burgundy. When King Rudolf II of Burgundy died in 937, the King of Italy, Hugh of Provence, tried to claim the Burgundian throne. Otto stepped in and supported Rudolf II's son, Conrad of Burgundy, who then became king. Burgundy became an important, but independent, part of Otto's influence.

Bohemia

In 935, Boleslaus I, Duke of Bohemia, became the ruler of Bohemia. After Otto's father died in 936, Boleslaus stopped paying tribute to the German Kingdom. He attacked Saxon allies and defeated two of Otto's armies. The war continued with border raids until 950. Otto besieged a castle owned by Boleslaus's son. Boleslaus then signed a peace treaty, agreeing to pay tribute again. Boleslaus became Otto's ally and helped the German army against the Magyars in 955.

Byzantine Empire

Early in his reign, Otto had good relations with Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus of the Byzantine Empire. They exchanged ambassadors. Otto also tried to arrange marriages to connect his family with the Eastern Empire.

Slavic Wars

In 939, while Otto was dealing with his brother's rebellion, the Slavs along the Elbe River revolted. They had been conquered by Otto's father and saw a chance to be free. Count Gero, Otto's leader in east Saxony, was in charge of controlling the pagan Slavs. Gero tricked about thirty Slavic leaders, inviting them to a banquet and then having his soldiers kill them. The Slavs sought revenge and marched against Gero. Otto supported Gero, and their combined forces pushed back the Slavs.

In 941, Gero used a captive Slav named Tugumir to help him. Tugumir was a chieftain who agreed to recognize Otto as his ruler if Gero helped him become prince. Tugumir became prince and declared loyalty to Otto. Otto gave Tugumir the title of "duke." This broke apart the Slavic federation. Otto and his successors expanded their control into Eastern Europe through military action and by establishing churches.

Otto's Campaigns in Italy

The Italian Throne Dispute

After Emperor Charles the Fat died in 888, Charlemagne's empire split into several kingdoms, including the Kingdom of Italy. The Pope in Rome crowned Italian kings as "emperors," but they had no power north of the Alps. When Berengar I of Italy was killed in 924, the imperial title was left empty.

Two kings, Rudolf II of Burgundy and Hugh of Provence, fought for control of Italy. Hugh won and became King of Italy in 926. His son Lothair became co-ruler in 931. In 940, Berengar II of Italy, a grandson of a former king, led a revolt against Hugh. Berengar II fled to Otto's court in 941. In 945, Berengar II returned and defeated Hugh. Hugh gave up his throne to his son Lothair. Lothair married 16-year-old Adelaide of Italy in 947. Lothair died in 950, and Berengar II crowned himself king, with his son Adalbert as co-ruler.

Berengar II tried to force Adelaide, who was the daughter, daughter-in-law, and widow of the last three Italian kings, to marry his son Adalbert. Adelaide refused and was imprisoned. She escaped and asked Otto for help and marriage. Marrying Adelaide would strengthen Otto's claim to the Italian throne and the emperorship. Otto knew she was smart and wealthy, so he accepted and prepared to go to Italy.

Otto's First Italian Trip

In early 951, before Otto marched to Italy, his son Liudolf, Duke of Swabia, invaded northern Italy. Liudolf's reasons are unclear. He might have wanted to help Adelaide or gain more power. Liudolf found no support and his army was struggling until Otto arrived. Otto was annoyed by his son's independent actions.

Otto and Liudolf's armies arrived in northern Italy in September 951. Berengar II offered no resistance. Italian nobles and clergy supported Otto. Berengar II fled from his capital, Pavia. When Otto reached Pavia on September 23, 951, the city welcomed him. On October 10, Otto was crowned with the Iron Crown of the Lombards. Like Charlemagne, Otto was now King of Germany and King of Italy. Otto then married Adelaide.

Soon after, Liudolf returned to Swabia. Archbishop Frederick of Mainz also returned to Germany. Problems in northern Germany forced Otto to go back across the Alps in 952 with most of his army. Otto left a small army in Italy and made his son-in-law, Conrad the Red, his regent. Conrad was tasked with defeating Berengar II.

Peace and Feudal Agreement

Conrad, with few troops, tried a diplomatic solution. He offered a peace treaty where Berengar II would remain King of Italy if he recognized Otto as his overlord. Berengar II agreed, and they traveled north to meet Otto.

Adelaide and Henry were unhappy with Conrad's treaty. Adelaide, being Italian, wanted Berengar II deposed. Henry, Duke of Bavaria, wanted to expand his territory into Italy. Conrad and Henry were already rivals. Adelaide and Henry convinced Otto to reject Conrad's treaty.

Conrad and Berengar II arrived to meet Otto but were made to wait three days. Otto referred the issue to a meeting of nobles. In August 952, at Augsburg, Berengar II and his son Adalbert swore loyalty to Otto as his vassals. Otto then gave Italy back to Berengar II as a fiefdom and restored his title "King of Italy." Berengar II had to pay a large yearly tribute and give up the Duchy of Friuli. Otto gave this territory to Henry, making Bavaria the most powerful region in Germany.

Otto and the Church

Starting in the late 940s, Otto used the Catholic Church to help him rule. He saw himself as the protector of the Church. He appointed unmarried church leaders, like bishops and abbots, to important government jobs. This helped him balance the power of the noble families. Otto gave land and titles to these appointed bishops and abbots. When they died, their offices went back to the king, preventing hereditary claims. This meant the king had great control over who became a bishop or abbot.

His own brother, Bruno the Great, was Otto's Chancellor and later became Archbishop of Cologne and Duke of Lorraine. Other important church officials in Otto's government included his son William, Archbishop of Mainz. Otto gave the Church lands and royal rights, like the power to collect taxes and raise an army. This made the Church powerful and loyal to the king. Otto also made tithing (giving a portion of income to the Church) mandatory in Germany.

Otto gave bishops and abbots the rank of count and their legal rights. Since Otto appointed all of them, these changes strengthened his central power. The German Church became like an arm of the royal government. Otto often appointed his personal chaplains to bishoprics. These chaplains worked for the government at court, and Otto rewarded them with promotions to lead dioceses.

Liudolf's Civil War

Rebellion Against Otto

Liudolf was unhappy after his Italian campaign failed and Otto married Adelaide. He started planning a rebellion. In December 951, he held a large feast attended by important figures, including Archbishop Frederick of Mainz. Liudolf convinced his brother-in-law, Conrad, Duke of Lorraine, to join him. Conrad felt betrayed by Otto's decision to make Berengar II a subject instead of an ally. Conrad and Liudolf believed Otto was being controlled by his foreign wife and power-hungry brother Henry.

In winter 952, Adelaide gave birth to a son, Henry. Rumors spread that Otto would make this new child his heir instead of Liudolf. Many nobles saw this as Otto focusing too much on Italy. This rumor pushed many nobles to rebel. Liudolf and Conrad first led nobles against Henry, Duke of Bavaria, in spring 953. Henry was unpopular in Bavaria, and his vassals quickly rebelled.

Otto heard about the rebellion and went to Mainz, where Archbishop Frederick tried to mediate. Otto left Mainz with a peace treaty that seemed good for the rebels. But when Otto returned to Saxony, Adelaide and Henry convinced him to cancel the treaty. Otto declared Liudolf and Conrad outlaws. He also said he still wanted to rule Italy and become emperor. He stirred up nobles in Lorraine against Conrad.

Otto's actions made people in Swabia and Franconia rebel. Liudolf and Conrad retreated to Mainz. In July 953, Otto and Henry's armies besieged Mainz. After two months, the city had not fallen, and more rebellions spread in southern Germany. Otto began peace talks. His youngest brother, Bruno, who was Archbishop of Cologne, helped. The rebels demanded the previous treaty be honored, but Henry's actions broke off talks. Conrad and Liudolf continued the war. Otto took away their duchies and made Bruno the new Duke of Lorraine.

While Otto was fighting, Henry appointed Arnulf II to govern Bavaria. Arnulf II, whose father Henry had replaced as duke, joined the rebellion. Otto and Henry tried to regain Bavaria but failed. Bavaria, Swabia, and Franconia were in open civil war. Even in Saxony, revolts began. By the end of 953, the civil war threatened to remove Otto from power.

Ending the Rebellion

In early 954, Margrave Hermann Billung, Otto's loyal supporter in Saxony, faced increased Slavic attacks. The Slavs took advantage of the German civil war. The Hungarians also raided southern Germany. Liudolf and Conrad defended their own areas, but the Hungarians devastated Bavaria and Franconia. On Palm Sunday, 954, Liudolf hosted Hungarian leaders and gave them gifts.

Otto's brother Henry spread rumors that Conrad and Liudolf had invited the Hungarians to Germany. Public opinion quickly turned against the rebels. Conrad began peace talks with Otto, joined by Liudolf and Archbishop Frederick. A truce was called, and Otto arranged a meeting of nobles on June 15, 954. Before the meeting, Conrad and Frederick made peace with Otto. But at the meeting, Henry accused Liudolf of working with the Hungarians. Liudolf, enraged, left to continue the civil war.

Liudolf and Arnulf II marched their army south to Regensburg in Bavaria, followed by Otto. They fought a battle, but it was not decisive. Liudolf retreated to Regensburg, where Otto besieged him. Otto's army could not break the city walls, but after two months, people inside starved. Liudolf sought peace, but Otto demanded unconditional surrender. Arnulf II was killed, and Liudolf fled to Swabia, with Otto's army close behind. They met at Illertissen and negotiated a truce. Liudolf agreed to accept any punishment from his father.

Archbishop Frederick died in October 954. With Liudolf's surrender, the rebellion ended everywhere except Bavaria. Otto called a meeting of nobles in December 954. Liudolf and Conrad swore loyalty to Otto and gave up their occupied territories. Otto did not give them back their ducal titles but let them keep their private lands. The meeting approved Otto's decisions:

- Liudolf was promised rule over Italy and command of an army against Berengar II.

- Conrad was promised military command against the Hungarians.

- Burchard III became Duke of Swabia.

- Bruno remained Duke of Lorraine.

- Henry was confirmed as Duke of Bavaria.

- Otto's son William became Archbishop of Mainz.

- Otto kept direct control over Saxony and Franconia.

These actions in December 954 ended the two-year civil war. Liudolf's rebellion, though difficult, ultimately made Otto an even stronger ruler of Germany.

Hungarian Invasions

The Hungarians (Magyars) invaded Otto's lands during Liudolf's civil war. They caused much damage in Southern Germany. The Principality of Hungary was a constant threat. In spring 954, the Hungarians invaded Bavaria. They reached the Rhine River, destroying much of Bavaria and Franconia.

Encouraged by their success, the Hungarians invaded Germany again in spring 955. Otto's army, now united, was ready. The Hungarians sent an ambassador for peace, but it was a trick. Otto's brother Henry warned him that the Hungarians had entered his territory. The main Hungarian army camped by the Lech River and besieged Augsburg. Bishop Ulrich of Augsburg defended the city while Otto gathered his army.

Otto and his army fought the Hungarians on August 10, 955, at the Battle of Lechfeld. Otto's forces included troops from Swabia and Bohemia. Even though they were outnumbered, Otto was determined to push the Hungarians out. Otto's army attacked the Hungarian lines, fighting them hand-to-hand. This prevented the Hungarians from using their usual shoot-and-run tactics. The Hungarians suffered heavy losses and had to retreat.

After the battle, Otto was called "Father of the Fatherland" and "Emperor." This battle ended almost 100 years of Hungarian invasions into Western Europe.

While Otto fought the Hungarians, the Obotrite Slavs in the north rebelled. Count Wichmann the Younger, still angry at Otto, raided Slavic lands. The Obotrites invaded Saxony in fall 955, killing men and taking women and children as slaves. Otto rushed north and pushed deep into their territory. The Slavs offered to pay tribute for self-rule, but Otto refused. They met on October 16 at the Battle of Recknitz. Otto's forces won a decisive victory, and hundreds of captured Slavs were executed.

Churches across the kingdom celebrated Otto's victories over the Hungarians and Slavs. These battles marked a turning point in Otto's reign. His victories secured his power over Germany, with the duchies firmly under his control. From 955 on, Otto faced no more rebellions.

Otto's son-in-law, Conrad, was killed at the Battle of Lechfeld. His brother Henry I, Duke of Bavaria, was badly wounded and died in November 955. Otto appointed his four-year-old nephew, Henry II, as the new duke, with his mother Judith as regent. Otto sent Liudolf to fight King Berengar II of Italy in 956, but Liudolf died of fever in September 957. Otto's first two sons with Adelaide also died young. Otto's third son with Adelaide, two-year-old Otto, became the new heir.

Otto Becomes Emperor

His Second Trip to Italy and Coronation

Liudolf's death in 957 left Otto without an heir and a commander for his fight against King Berengar II of Italy. Berengar II was a rebellious ruler. After Liudolf and Henry I died, and with Otto campaigning in northern Germany, Berengar II attacked the March of Verona in 958. He also attacked the Papal States and Rome, ruled by Pope John XII. In autumn 960, with Italy in chaos, the Pope asked Otto for help against Berengar II. Other important Italian leaders also asked Otto for help.

The Pope agreed to crown Otto as Emperor. Otto prepared his army for a second Italian campaign. In May 961, Otto named his six-year-old son, Otto II, as his heir and co-ruler. Otto II was crowned at Aachen Cathedral on May 26, 961. Otto appointed his brother Bruno and his son William as Otto II's co-regents in Germany.

Otto's army entered northern Italy in August 961. He moved towards Pavia, the old Lombard capital, where he celebrated Christmas and took the title "King of Italy." Berengar II's armies avoided battle, so Otto advanced without opposition. Otto reached Rome on January 31, 962. Three days later, on February 2, he was crowned Emperor by Pope John XII at Old St. Peter's Basilica. The Pope also crowned Otto's wife, Adelaide, as empress. With Otto's coronation, the Kingdom of Germany and the Kingdom of Italy were united into one realm, later called the Holy Roman Empire.

Dealing with the Pope

On February 12, 962, Emperor Otto I and Pope John XII held a meeting in Rome. They made their relationship official. Pope John XII approved Otto's plan for the Archdiocese of Magdeburg. Otto wanted this archdiocese to celebrate his victory at Lechfeld and to help convert the Slavs to Christianity.

The next day, Otto and John XII signed the Diploma Ottonianum. This document confirmed John XII as the Church's spiritual leader and Otto as its protector. Otto recognized the Pope's control over the Papal States and even expanded them. However, Otto never gave up real control over these extra territories. The Diploma also said that only the clergy and people of Rome could elect the Pope. But the chosen Pope had to swear loyalty to the Emperor before being confirmed. This meant the Emperor had power over the Pope.

With the Diploma signed, Otto marched against Berengar II. Berengar II surrendered in 963. After Otto's successful campaign, John XII became worried about the Emperor's growing power. He started talking with Berengar II's son, Adalbert, about removing Otto. The Pope also sent messages to the Hungarians and the Byzantine Empire to join an alliance against Otto. Otto found out about the Pope's plan. After defeating and imprisoning Berengar II, Otto marched on Rome. John XII fled. Otto called a council, removed John XII as Pope, and appointed Leo VIII as the new Pope.

Otto and the Roman People

Otto sent most of his army back to Germany by the end of 963, thinking his rule in Italy was secure. But the Roman people did not like Leo VIII, who was not a trained church leader. In February 964, the Romans forced Leo VIII to flee. They then brought back John XII. When John XII died in May 964, the Romans elected Pope Benedict V. Otto heard about this and returned to Rome with new troops. In June 964, he besieged the city. Otto forced the Romans to accept Leo VIII as Pope and sent Benedict V away.

Otto's Third Trip to Italy

Otto returned to Germany in January 965. On May 20, 965, Margrave Gero, Otto's loyal leader on the eastern border, died. He left a large territory. Otto divided this into five smaller areas, each ruled by a margrave.

Peace in Italy did not last long. Adalbert, the son of the deposed King Berengar II, rebelled against Otto. Otto sent Burchard III of Swabia to stop the rebellion. Burchard III defeated the rebels in June 966, bringing Italy back under Otto's control. Pope Leo VIII died in March 965. The Church, with Otto's approval, elected John XIII as the new Pope in October 965. John XIII's arrogant behavior made him unpopular. In December, the Roman people arrested him, but he escaped. The Pope asked for help, and Otto prepared his army for a third trip to Italy.

In August 966, Otto announced how Germany would be governed while he was away. His son William, Archbishop of Mainz, would be regent for all of Germany. Margrave Hermann Billung would manage Saxony. Otto left his heir with William and led his army into northern Italy.

Ruling from Rome

When Otto arrived in Italy, John XIII was restored to his papal throne in November 966. Otto captured the twelve leaders of the rebel group who had removed the Pope and had them executed. Otto then lived in Rome and traveled with the Pope to Ravenna for Easter in 967. A meeting confirmed Magdeburg's status as a new archdiocese.

Otto continued to expand his empire south. In February 967, Prince Pandolf Ironhead of Benevento accepted Otto as his overlord. This caused conflict with the Byzantine Empire, which claimed southern Italy. The Byzantines also did not like Otto using the title "Emperor," believing only their emperor was the true successor of the Roman Empire.

The Byzantines began peace talks with Otto. Otto wanted a Byzantine princess for his son Otto II to marry. This would give his family more legitimacy and prestige. To prepare for his son's marriage, Otto returned to Rome in winter 967. He had Otto II crowned co-Emperor by Pope John XIII on Christmas Day 967. Otto II had no real power until his father died.

In the following years, both empires fought to control southern Italy. In 969, John I Tzimiskes became the new Byzantine Emperor. He finally recognized Otto's imperial title. In 972, he sent his niece Theophanu to Rome, and she married Otto II on April 14, 972. This peace deal resolved the conflict over southern Italy. The Byzantine Empire accepted Otto's rule over some southern Italian areas. In return, Otto pulled back from Byzantine lands in Apulia and Calabria.

Otto's Final Years and Death

With his son's wedding done and peace with the Byzantine Empire, Otto led his family back to Germany in August 972. In spring 973, the Emperor visited Saxony. He celebrated Easter in Quedlinburg with a large gathering. According to a historian, Otto received leaders from Poland, Bohemia, Byzantium, Rome, Hungary, Bulgaria, Denmark, and other Slavic lands. Ambassadors from England and Spain also arrived later that year.

Otto traveled to his palace at Memleben, where his father had died years earlier. There, Otto became very ill with a fever. He died on May 7, 973, at the age of 60.

The transfer of power to his 17-year-old son, Otto II, was smooth. On May 8, 973, the lords of the Empire confirmed Otto II as their new ruler. Otto II arranged a grand funeral for his father. Otto I was buried next to his first wife, Eadgyth, in Magdeburg Cathedral.

Otto's Family and Children

| German royal dynasties | |

|---|---|

| Ottonian dynasty | |

|

Chronology

|

|

| Henry I |

919 – 936

|

| Otto I |

936 – 973

|

| Otto II |

973 – 983

|

| Otto III |

983 – 1002

|

| Henry II |

1002 – 1024

|

|

Family

|

|

| Ottonian dynasty family tree Family tree of the German monarchs Category:Ottonian dynasty |

|

|

Succession

|

|

| Preceded by Conradine dynasty | |

| Followed by Salian dynasty | |

Otto's father, Henry I, founded the Ottonian dynasty. Otto I was Henry I's son, Otto II's father, Otto III's grandfather, and Henry II's great-uncle. The Ottonians ruled Germany (later the Holy Roman Empire) for over a century, from 919 to 1024.

Otto had two wives and at least seven children, including one illegitimate child.

- With an unknown Slavic woman:

- William (929 – March 2, 968) – Archbishop of Mainz from 954 until his death.

- With Eadgyth of England, daughter of King Edward the Elder:

- Liudolf (930 – September 6, 957) – Duke of Swabia from 950 to 954. He was expected to be Otto's successor.

- Liutgarde (932–953) – Married Conrad, Duke of Lorraine, in 947.

- With Adelaide of Italy, daughter of King Rudolf II of Burgundy:

- Henry (952–954)

- Bruno (probably 954–957)

- Matilda (954–999) – Abbess of Quedlinburg from 966 until her death.

- Otto II (955 – December 7, 983) – Holy Roman Emperor from 973 until his death.

Otto's Legacy

The Ottonian Renaissance

During Otto's time and that of his immediate successors, there was a small rebirth of arts and architecture. This period is called the Ottonian Renaissance. It included the revival of some cathedral schools, like the one led by Bruno I, Archbishop of Cologne. It also saw the creation of beautiful illuminated manuscripts, which were the main art form of the time. Important convents, like Quedlinburg Abbey (founded by Otto in 936), were led by women from the royal family.

Otto in the Modern World

Otto I was chosen as the main design for a special €100 coin from Austria in 2008. One side shows the Imperial Crown of the Holy Roman Empire. The other side shows Emperor Otto I with Old St. Peter's Basilica in Rome in the background, where he was crowned. Several exhibitions in Magdeburg have also shown Otto's life and his impact on medieval European history.

See also

In Spanish: Otón I del Sacro Imperio Romano Germánico para niños

In Spanish: Otón I del Sacro Imperio Romano Germánico para niños