Duchy of Bavaria facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Duchy of Bavaria

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 555–1805 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Wittelsbach arms of the dukes of Bavaria (until 1623)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

Duchy of Bavaria (red) within the Holy Roman Empire c. 1000.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

Duchy of Bavaria within the Holy Roman Empire, 1618.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Stem duchy and vassal of the Merovingians (the so-called older stem duchy) (c. 555–788) Direct rule under the Carolingians, as Kings of Bavaria (788–843) Stem duchy of East Francia and the Kingdom of Germany (the so-called younger stem duchy) (843–962) State of the Holy Roman Empire (from 962) |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Regensburg (until 1255) Munich (from 1505) |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Bavarian, Latin | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism (official) Lutheranism |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Bavarian | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Feudal monarchy | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Duke | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 555–591

|

Garibald I (first) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1597–1623

|

Maximilian I (last) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Medieval Europe | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Garibald I as vassal of the Merovingians, first documented duke

|

c. 555 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Directly ruled part of the Carolingian Empire

|

788 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Margrave Arnulf

assumed ducal title |

907 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Carinthia split off

|

976 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Austria split off

|

1156 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• To House of Wittelsbach

|

1180 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• First partition

|

1255 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Reunification

|

1503 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Raised to Electorate

|

1623 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1805 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||||||||||

The Duchy of Bavaria (German: Herzogtum Bayern) was an important region in Europe for many centuries. It started around 555 AD in the southeastern part of the Merovingian kingdom. This area was home to Bavarian tribes and was ruled by leaders called dukes. These dukes were under the control of the powerful Frankish kings.

Later, as the Carolingian Empire became weaker in the late 800s, a new Duchy of Bavaria was formed. It became one of the main "stem duchies" (large, important regions) of the East Frankish realm. This realm eventually grew into the Kingdom of Germany and the mighty Holy Roman Empire.

Over time, Bavaria's territory changed. In 976, the new Duchy of Carinthia was separated from it. Between 1070 and 1180, the dukes of Bavaria, especially from the House of Welf, often disagreed with the Holy Roman Emperors. Eventually, in 1180, Duke Henry the Lion lost his lands. Bavaria was then given to the House of Wittelsbach, a family that ruled Bavaria for a very long time, until 1918. The Bavarian dukes became "prince-electors" (important leaders who could help choose the Emperor) in 1623 during the Thirty Years' War. Later, in 1806, Napoleon made them kings.

Contents

Where Was Bavaria?

The medieval Bavarian stem duchy covered a large area. It included parts of what is now Southeastern Germany and most of Austria. It stretched along the Danube river, reaching the Hungarian border in the east.

This area included the "Altbayern" regions of modern Bavaria, plus the lands of the Nordgau (which later became the Upper Palatinate). However, it did not include the Swabian and Franconian parts of today's Bavaria.

Over the centuries, Bavaria's size changed. In 976, the Duchy of Carinthia was created, meaning Bavaria lost large parts of the Eastern Alps. These areas are now parts of Carinthia and Styria in Austria, and the Carniolan region in Slovenia. Also, the eastern part called the March of Austria (which is now Lower Austria) became its own duchy in 1156.

Later, other areas like the County of Tyrol and the Archbishopric of Salzburg also became independent from Bavaria. By 1500, many of these independent states were part of the "Bavarian Circle" within the Holy Roman Empire.

A Look Back: Bavarian History

Early Beginnings: The Older Duchy

The first signs of the older Bavarian duchy appeared around 551 to 555 AD. A writer named Jordanes mentioned the "Bavarii" living to the east of the Swabians.

The Agilolfings Family

The first dukes of Bavaria belonged to the Agilolfings family. They ruled the area from the Nordgau region (later the Upper Palatinate) all the way to the Enns river in the east. Their lands also stretched south across the Brenner Pass into what is now South Tyrol. The first known duke was Garibald I, who started ruling in 555. He was from the Frankish Agilolfings and was mostly independent, but still a "vassal" (a ruler who owes loyalty to a more powerful king) of the Merovingian kings.

Changes happened on the eastern border. The Lombards moved from the Pannonia region to northern Italy in 568. Then, the Avars took their place, and Czechs settled nearby. Around 743, the Bavarian duke Odilo helped the Slavic princes of Carantania (a region in the Eastern Alps) who needed protection from the Avars. The main city for these mostly independent Agilolfing dukes was Regensburg, which used to be a Roman fort.

During this time, Christianity spread. Bishop Corbinian helped set up the Diocese of Freising before 724. Saint Kilian had been a missionary in the north, and Boniface founded the Diocese of Würzburg in 742. In the west, Augsburg was a bishop's seat. When Boniface created the Diocese of Passau in 739, there were already some Christian traditions there. In the south, Saint Rupert founded the Diocese of Salzburg in 696. He likely baptized Duke Theodo of Bavaria and became known as the "Apostle of Bavaria." In 798, Pope Leo III made Salzburg the main church center for Bavaria, with Regensburg, Passau, Freising, and Säben (later Brixen) as important local dioceses.

The Carolingian Era

As the Frankish Empire grew stronger under the Carolingian dynasty, the Bavarian dukes lost their independence. By 716, the Carolingians had taken over the northern Franconian lands. In 746, the Carolingian leader Carloman stopped the last Alamannic revolt. Bavaria was the last major region to be fully taken over in 788. This happened after Duke Tassilo III tried to stay independent by making an alliance with the Lombards, but failed. Charlemagne, the famous Frankish emperor, conquered the Lombard Kingdom, which led to Tassilo's removal in 788. After that, Frankish officials called "prefects" governed Bavaria. Gerold was the first, ruling from 788 to 799.

Taking over Bavaria made the neighboring Avars angry. In 788, the Avars attacked Bavaria, but Frankish and Bavarian forces pushed them back. They then counterattacked Avar lands along the river Danube, east of the Enns river. The two sides fought near the Ybbs, where the Avars were badly defeated in 788.

To make Bavaria's eastern borders safe, Charlemagne came to Bavaria himself in the autumn of 788. In Regensburg, he held a meeting and organized the border regions, preparing for future actions in the east. In 790, the Avars tried to make peace, but no agreement was reached.

Bavaria then became the main base for the Frankish campaign against the Avars, which began in 791. A large Frankish army, led by Charlemagne, crossed from Bavaria into Avar territory. They advanced along the river Danube but met little resistance. They soon reached the Vienna Woods, near the Pannonian Plain. No big battles were fought because the Avars fled.

The Franks gaining new eastern regions, especially between the Enns river and the Vienna Woods, made Bavaria much safer. This area was first under the Bavarian prefect Gerold and later became known as the (Bavarian) "Eastern March" (marcha orientalis). It protected Bavaria's eastern borders and secured the main route between Frankish lands in Bavaria and Pannonia.

The Younger Duchy of Bavaria

In 817, Charlemagne's son, Emperor Louis the Pious, tried to keep the Carolingian Empire united. He planned for his eldest son, Lothair I, to become emperor, while his younger sons would get smaller kingdoms. From 825, Louis the German called himself "King of Bavaria," and this area became the center of his power. When the brothers divided the Empire in 843 with the Treaty of Verdun, Bavaria became part of East Francia under King Louis the German. When he died in 876, he gave the Bavarian royal title to his eldest son Carloman.

Carloman's son, Arnulf of Carinthia, grew up in the Carantanian lands. After his father's death in 880, he took control of the March of Carinthia and became King of East Francia in 887. Carinthia and Bavaria were the bases of his power, with Regensburg as his government's main city.

Thanks to the support of the Bavarians, Arnulf was able to challenge Charles in 887 and become German king the next year. In 899, Bavaria passed to Louis the Child. During his rule, there were constant attacks from the Hungarians. Resistance grew weaker, and it is said that on July 5, 907, almost all the Bavarian warriors died in the Battle of Pressburg against these strong enemies.

During Louis the Child's reign, Luitpold, a powerful count, ruled the Mark of Carinthia. This area was created on the southeastern border to defend Bavaria. Luitpold died in the big battle of 907. But his son, Arnulf, gathered the remaining Bavarians. He made an alliance with the Hungarians and became duke of the Bavarians in 911, uniting Bavaria and Carinthia under his rule. The German king Conrad I attacked Arnulf without success when Arnulf refused to accept his royal authority.

Luitpoldings and Ottonians

The Carolingian rule in East Francia ended in 911 when King Louis the Child died without children. This lack of a strong central ruler led to the German "stem duchies" becoming powerful again. At the same time, East Francia faced a growing threat from Hungarian invasions, especially in the Bavarian March of Austria (marchia orientalis) beyond the Enns river. In 907, the army of Luitpold, Margrave of Bavaria suffered a huge defeat at the Battle of Pressburg. Luitpold himself was killed, and his son Arnulf the Bad took the title of duke. He was the first Duke of Bavaria from the Luitpolding dynasty. However, the Austrian march remained under Hungarian control, and the Pannonian lands were lost forever.

The strong will of the Bavarian dukes caused ongoing arguments in the new Kingdom of Germany. Duke Arnulf's son Eberhard was removed from power by King Otto I of Germany in 938. His younger brother Berthold took his place. In 948, King Otto finally took power away from the Luitpoldings. He made his younger brother Henry I the Duke of Bavaria. The young heir of Duke Berthold, Henry III, was given a less important role as a Bavarian "Count palatine." The last attempt by the Luitpoldings to regain power, by joining a rebellion led by King Otto's son Liudolf of Swabia, was crushed in 954.

In 952, Duke Henry I also received the Italian March of Verona. Otto I had taken this from King Berengar II of Italy. Henry still had to deal with the Hungarian threat. This threat was finally removed after King Otto's victory at the 955 Battle of Lechfeld. The Magyars (Hungarians) retreated behind the Leitha and Morava rivers. This allowed a second wave of German settlers to move into the areas of today's Lower Austria, Istria, and Carniola.

Even though the dukes were now from the Ottonian family (a branch of the Saxon royal family), the conflict between the Bavarian dukes and the German (and later Imperial) court continued. In 976, Emperor Otto II removed his rebellious cousin Duke Henry II of Bavaria. He then created the Duchy of Carinthia from former Bavarian land. This new duchy was given to the former Luitpolding Count palatine Henry III, who also became Margrave of Verona. Although Henry II made peace with Emperor Otto's widow Theophanu in 985 and got his duchy back, the power of the Bavarian dukes was further reduced. This was due to the rise of the Franconian House of Babenberg, who ruled as Margraves of Austria (Ostarrichi) and became more and more independent.

The Welf Family

The last Ottonian duke, Henry IV of Bavaria, was chosen as King of the Romans in 1002, becoming Henry II. At different times, the duchy was ruled by the German kings themselves, by dukes who depended on the king, or even by the emperor's sons. This tradition continued with Henry's Salian successors. During this time, many noble families, like the Counts of Andechs and the House of Wittelsbach, became powerful. In 1061, the Empress Agnes of Poitou gave the Duchy of Bavaria to the Saxon count Otto of Nordheim. However, her son King Henry IV took the duchy back for unfair reasons. This eventually led to the Saxon Rebellion in 1073. Henry then gave Bavaria to Welf, who was from the House of Este and started the Welf dynasty. This family ruled the duchy on and off for the next 110 years.

The Bavarian dukes became strong again only when the Welf family started ruling in 1070. This period was marked by the Investiture Controversy, a big disagreement between the Emperor and the Pope. The Welfs sided with the Pope, which made their rule even stronger.

After Henry V, the last Salian emperor, died in 1125, Lothair III was chosen as emperor. The Bavarian duke Henry the Proud had married Lothair's daughter, Gertrude, and was promised her inheritance. When a conflict started with anti-king Conrad III, a nephew of Henry V, the Bavarian duke supported Lothair. This made Henry the Proud even more powerful and increased his chances of being chosen as King of Germany and Duke of Saxony after Lothair's death. However, Conrad III was successfully elected King of Germany in 1138. Fearing Henry's power, Conrad refused to make Henry the Duke of Saxony, saying it was against the law for one duke to hold two duchies. Because of this, and his anger about not becoming king, Henry refused to swear loyalty to Conrad. As a result, he lost all his lands, and Bavaria was given to his half-brother Leopold IV, Margrave of Austria in 1139.

The Duchy of Swabia was mostly countryside during the rule of the Staufer kings. Franconia became the center of Staufer power. This lasted until 1168, when the Bishop of Würzburg gained control of the diocese of Bamberg and became the Duke of Franconia. The Hohenstaufen emperor Frederick I Barbarossa tried to make peace with the Welfs. In 1156, he gave the Duchy of Bavaria back to Henry the Lion of the Welf family. However, the East Mark (Austria) stayed with the Babenberg family. It was made into the Duchy of Austria to make up for the loss of Bavaria. This elevation of the Marcha Orientalis under the Babenbergs created the core of what would later become the country of Austria.

Henry the Lion founded many cities, including Munich in 1158. His strong position as ruler of both Saxony and Bavaria led to conflicts with Frederick I Barbarossa. When Henry the Lion was banished, and the March of Styria was separated from Bavaria (becoming the Duchy of Styria in 1180), the younger tribal duchy of Bavaria came to an end.

The Wittelsbach Family Takes Over

From 1180 until 1918, the Wittelsbach family ruled Bavaria. They were dukes, then electors, and finally kings. When Count Palatine Otto VI of Wittelsbach became Otto I, Duke of Bavaria in 1180, the Wittelsbach family was not very rich. But over the next years, they gained a lot of wealth and land through buying, marriages, and inheritances. New lands they acquired were no longer given away as fiefs (lands given in exchange for loyalty), but managed directly by their own officials. Also, powerful families like the Counts of Andechs died out during this time. Otto's son, Ludwig I of Wittelsbach, was given the County Palatine of the Rhine in 1214.

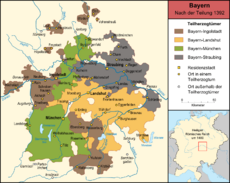

The Wittelsbach family did not have a rule where the firstborn son always inherited everything. Because of this, in 1255, Bavaria was divided into two parts: Upper Bavaria (with the Palatinate and Nordgau, centered in Munich) and Lower Bavaria (with centers in Landshut and Burghausen). Even today, Bavaria is often divided into "Upper" and "Lower" regions.

Even though Bavaria was divided again after a short time of being united, it became very powerful under Louis IV, Holy Roman Emperor, who was the first Wittelsbach emperor in 1328. However, new areas gained, like Brandenburg (1323), Tyrol (1342), and parts of the Netherlands (1345), were lost by his successors. In 1369, Tyrol went to the Habsburg family. Other lands were lost in 1373 and 1436. In the 1329 Treaty of Pavia, Emperor Louis divided his lands into a Palatine region and what was later called the Upper Palatinate. This meant the right to help choose the emperor (the "electoral dignity") went to the Palatinate branch of the family. In 1275, Salzburg became largely independent from Bavaria. When the Archbishop of Salzburg issued its own laws in 1328, Salzburg became a mostly independent state within the Holy Roman Empire.

In the 14th and 15th centuries, Upper and Lower Bavaria were divided many times. After the division of 1392, there were four duchies: Bavaria-Straubing, Bavaria-Landshut, Bavaria-Ingolstadt, and Bavaria-Munich. These dukes often fought each other. Duke Albrecht IV of Bavaria-Munich finally united Bavaria in 1503 through a war and a new rule that the firstborn son would inherit everything (primogeniture). However, some original Bavarian areas like Kufstein, Kitzbühel, and Rattenberg in Tirol were lost in 1504.

Even with the new rule, Albert's oldest son William IV had to share power with his brother Louis X in 1516. This lasted until Louis died in 1545. William continued the Wittelsbach policy of opposing the Habsburgs until 1534, when he made a treaty with Ferdinand I, the king of Hungary and Bohemia. This alliance grew stronger in 1546 when Emperor Charles V got William's help during the war against the Schmalkaldic League. In return, Charles promised William the chance to inherit the Bohemian throne and the important "electoral dignity" (the right to help choose the Emperor). William also worked hard to keep Bavaria Catholic during a difficult time. He gained more control over bishoprics and monasteries from the Pope. He then took steps to stop the Protestant reformers, banishing many of them. The Jesuits, whom he invited to Bavaria in 1541, made their main base in Germany at Ingolstadt. William died in March 1550 and was followed by his son Albert V, who had married a daughter of Ferdinand I. Early in his rule, Albert made some small agreements with the reformers, who were still strong in Bavaria. But around 1563, he changed his mind, supported the decisions of the Council of Trent, and pushed forward the Counter-Reformation (the Catholic Church's response to the Protestant Reformation). As education increasingly came under the control of the Jesuits, the spread of Protestantism was effectively stopped in Bavaria.

The next duke, Albert's son William V, had a Jesuit education and was very devoted to Jesuit beliefs. He secured the important Archbishopric of Cologne for his brother Ernest in 1583. This high position stayed in the family for over 200 years. In 1597, William gave up his rule to his son Maximilian I.

Maximilian I found the duchy in debt and disorder. But in just ten years of his strong rule, he made amazing changes. He reorganized the finances and the justice system, created a group of civil servants, and started a national army. He also brought several small areas under his control. This led to a strong and orderly duchy, which allowed Maximilian to play a big role in the Thirty Years' War. During the early years of the war, he was so successful that he gained the Upper Palatinate and the important "electoral dignity" that the older branch of the Wittelsbach family had held since 1356. The Electorate of Bavaria then included most of the modern regions of Upper Bavaria, Lower Bavaria, and the Upper Palatinate.

More to Explore

- List of rulers of Bavaria

Sources

de:Geschichte Bayerns#Das jüngere baierische Stammesherzogtum