Berengar I of Italy facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Berengar of Friuli |

|

|---|---|

| Emperor of the Romans | |

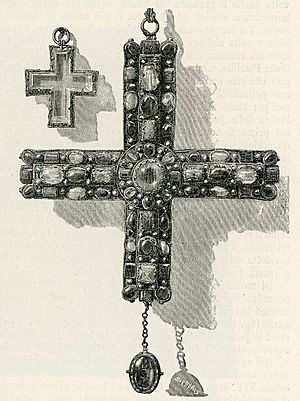

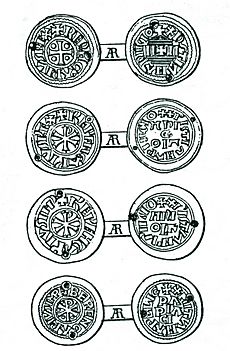

Berengar's imperial seal

|

|

| Emperor in Italy | |

| Reign | 915–924 |

| Coronation | December 915, Rome |

| Predecessor | Louis the Blind |

| Successor | Otto I |

| Born | c. 845 Cividale, Middle Francia |

| Died | 7 April 924 Verona, Kingdom of Italy |

| Spouse | Bertila of Spoleto; Anna |

| Issue | Bertha, Abbess of Santa Giulia in Brescia Gisela, Countess of Ivrea |

| House | Unruochings |

| Father | Eberhard of Friuli |

| Mother | Gisela, daughter of Louis the Pious |

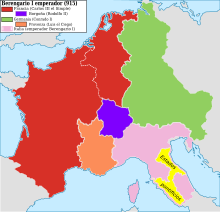

Berengar I (born around 845 – died April 7, 924) was a powerful ruler in early medieval Europe. He was the king of Italy starting in 887. Later, he also became the Holy Roman Emperor from 915 until his death in 924.

People usually call him Berengar of Friuli. This is because he controlled the March of Friuli from 874. The March of Friuli was an important border region in northeastern Italy. Berengar's long reign lasted 36 years. It was a very challenging time. He faced many rivals who wanted to be king of Italy. Also, fierce Magyar raiders often attacked Western Europe during his rule. After Berengar died, there was no emperor for 38 years. This period ended when Otto I became emperor in 962.

Contents

Early Life and Power

Berengar belonged to a family called the Unruochings. His grandfather was Unruoch II. Berengar's father was Eberhard of Friuli. His mother was Gisela. She was the daughter of Louis the Pious, a famous emperor. This meant Berengar was related to the important Carolingian royal family through his mother. He was probably born in a place called Cividale.

At some point, Berengar married Bertilla. She was the daughter of a powerful family called the Supponids. Bertilla was very influential and helped him rule.

In 874, Berengar became the ruler of the March of Friuli. This happened after his older brother, Unruoch III, passed away. This position was very important. Friuli was a border area next to the Croats and other Slavic groups. These groups often threatened Italy. Berengar became a powerful leader in northeastern Italy. He helped people in Friuli connect with the emperor. He also had a lot of influence over the church in Friuli.

When Emperor Louis II died in 875, there was a fight for control of Italy. Charles the Bald from West Francia invaded and became king and emperor. But Louis the German sent his sons, including Charles the Fat, to take Italy back. Berengar and other Italian leaders helped them. This shows how important Berengar was.

In 883, Guy III of Spoleto was accused of treason. Emperor Charles the Fat sent Berengar with an army to fight Guy. Berengar was successful at first. But a sickness spread through Italy, and his army had to leave.

Berengar had a disagreement with Liutward, the Bishop of Vercelli, in 886. Berengar attacked Vercelli and took the bishop's belongings. The reason for this fight is not fully clear. But they made peace before Liutward left the emperor's court in 887.

After this, Berengar lost some favor with the emperor. He attended a meeting with the emperor in May 887. He gave many gifts to make peace. Later, he was present when Louis of Provence was adopted as the emperor's son. Some people think Berengar wanted to be Charles's heir. He was indeed made king of Italy right after Charles was removed from power in November 887.

King of Italy: Challenges and Victories

Berengar became king of Italy between December 887 and January 888. He was crowned in Pavia. However, he was not the only powerful leader in Italy. He might have made a deal with his old rival, Guy of Spoleto. The deal was that Guy would rule West Francia and Berengar would rule Italy. Both Guy and Berengar were related to the Carolingian royal family. Berengar was seen as favoring Germany, while Guy favored France.

In 888, Guy returned to Italy after failing to become king of West Francia. He gathered an army to fight Berengar. They fought near Brescia. Berengar won a small victory, but his army was weakened. They agreed to a truce until January 889.

After the truce, Arnulf of Germany tried to invade Italy. Berengar met with Arnulf and agreed to be his vassal. This meant Berengar would rule Italy under Arnulf's authority.

In early 889, Guy defeated Berengar at the Battle of the Trebbia. Guy then became the sole king in Italy. But Berengar still controlled Friuli. Even though Guy had support from Pope Stephen V, the Pope later turned to Arnulf. Arnulf continued to support Berengar.

In 893, Arnulf sent his son Zwentibold to Italy. Zwentibold and Berengar cornered Guy in Pavia. But they did not press their advantage, possibly because Guy bribed them. In 894, Arnulf and Berengar defeated Guy. They took control of Pavia and Milan. Berengar was with Arnulf's army when it invaded Italy in 896. However, Berengar left the army and returned to Lombardy. There were rumors that Berengar had turned against Arnulf. Because of this, Berengar lost control of Friuli.

Arnulf left Italy in the care of his young son, Ratold. But Ratold soon returned to Germany. This left Italy under Berengar's control. Berengar then made a deal with Lambert, Guy's son. They agreed to divide the kingdom. Berengar would rule the eastern half. This agreement confirmed the situation from 889.

The peace did not last long. Berengar attacked Pavia but was defeated and captured by Lambert. However, Lambert died just days later, in October 898. Berengar quickly took control of Pavia and became the sole ruler.

During this time, the Magyars began their first attacks on Western Europe. They invaded Italy in 899. Berengar gathered a large army to fight them. He refused their request for a truce. But his army was surprised and defeated near the Brenta River in the Battle of the Brenta in September 899.

This defeat weakened Berengar. The nobles began to doubt his ability to protect Italy. They invited Louis of Provence to become king. In 900, Louis marched into Italy and defeated Berengar. The next year, Pope Benedict IV crowned Louis as Emperor. But in 902, Berengar fought back and defeated Louis. He made Louis promise never to return to Italy. Louis broke his promise and invaded again in 905. Berengar defeated him in Verona, captured him, and ordered him to be blinded in July. Louis returned to Provence and ruled as Louis the Blind for another twenty years. This victory made Berengar's position as king much stronger. He ruled without major challenges until 922. Berengar made Verona his main city and fortified it heavily.

In 904, the city of Bergamo was under a long siege by the Magyars. After the siege, Berengar gave the bishop of Bergamo the right to rebuild the city walls. He also gave the bishop all the rights of a count in the city.

Emperor and Final Years

In January 915, Pope John X tried to create an alliance. He wanted Berengar and other Italian rulers to fight the Saracen threat in southern Italy. Berengar could not send many troops. But after a great victory over the Saracens at the Battle of the Garigliano, Pope John crowned Berengar as Emperor in Rome in December. Berengar quickly returned north. Friuli was still being threatened by the Magyars.

As emperor, Berengar even got involved in a church election outside Italy. In 920, he supported a monk named Richer to become Bishop of Liège. This showed his influence beyond Italy.

In his later years, his wife Bertilla was poisoned. By December 915, he had married again to a woman named Anna. Some historians believe Anna was the daughter of Louis of Provence. This marriage might have been an attempt to connect Berengar to another powerful royal family.

Berengar's older daughter, Bertha, was an abbess at a monastery in Brescia. Berengar gave her monastery special rights to build defenses. His younger daughter, Gisela of Friuli, married Adalbert I of Ivrea. However, this marriage did not create a strong alliance. Gisela died by 913. Adalbert later became one of Berengar's enemies.

Between 917 and 920, Adalbert and other nobles invited Hugh of Arles to take the Italian throne. Hugh invaded Italy and reached Pavia. Berengar managed to force them to surrender. He allowed them to leave Italy safely.

Many Italian nobles were unhappy with Berengar. They felt he was not protecting them well. They invited Rudolph II of Upper Burgundy to become king in 921. Even Berengar's own grandson, Berengar of Ivrea, turned against him. Berengar retreated to Verona. He had to watch as the Magyars attacked the country. In 922, the Bishop of Pavia surrendered his city to Rudolph. The Magyars then sacked Pavia in 924.

On July 29, 923, Rudolph's forces, along with Adalbert and Berengar of Ivrea, fought Berengar's army. They defeated him at the Battle of Fiorenzuola. This battle was a major loss for Berengar. He was effectively removed from power and replaced by Rudolph. Soon after, Berengar was murdered in Verona by one of his own men. He had no sons, only his two daughters, Bertha and Gisela.

Some historians have criticized Berengar. They say he was not very good at fighting battles against his rivals. They also say he gave away too much land to private owners, like bishops. However, others see his actions as a way to encourage local defense. His rule certainly played a part in the building of many castles in the years that followed.

Sources

- Arnaldi, Girolamo. "Berengario I, duca-marchese del Friuli, re d'Italia, imperatore" Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani 9. Rome: Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana, 1967.

- "Berengar." (2007). Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 14 May 2007.

- Daris, Joseph. Histoire du Diocèse et de la Principalité de Liège: depuis leur origine jusqu'au XIIIe siècle, Volume 1. Éditions Culture et Civilisation, 1980.

- Llewellyn, Peter. Rome in the Dark Ages. London: Faber and Faber, 1970. ISBN: 0-571-08972-0.

- MacLean, Simon. Kingship and Politics in the Late Ninth Century: Charles the Fat and the end of the Carolingian Empire. Cambridge University Press: 2003.

- Previté-Orton, C. W. "Italy and Provence, 900–950." The English Historical Review, Vol. 32, No. 127. (Jul., 1917), pp 335–347.

- Reuter, Timothy (trans.) The Annals of Fulda. (Manchester Medieval series, Ninth-Century Histories, Volume II.) Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1992.

- Reuter, Timothy. Germany in the Early Middle Ages 800–1056. New York: Longman, 1991.

- Rosenwein, Barbara H. "The Family Politics of Berengar I, King of Italy (888–924)." Speculum, Vol. 71, No. 2. (Apr., 1996), pp 247–289.

- Tabacco, Giovanni. The Struggle for Power in Medieval Italy: Structures and Political Rule. (Cambridge Medieval Textbooks.) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

- Wickham, Chris. Early Medieval Italy: Central Power and Local Society 400–1000. MacMillan Press: 1981.

|

Emperor Berengar

Unruoching dynasty

Died: 7 April 924 |

||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Unruoch III |

Margrave of Friuli 874–890 |

Succeeded by Waltfred |

| Preceded by Charles the Fat |

— DISPUTED — King of Italy 887–924 Disputed by Guy III of Spoleto (888–894) Lambert II of Spoleto (891–898) Arnulf of Carinthia (896–899) Ratold (896) Louis the Blind (900–905) Rudolph II of Upper Burgundy (922–933) |

Succeeded by Rudolph as contenders |

| Preceded by Louis the Blind |

Holy Roman Emperor 915–924 |

Vacant

Title next held by

Otto I |

See also

In Spanish: Berengario del Friul para niños

In Spanish: Berengario del Friul para niños

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |