Alemanni facts for kids

The Alemanni or Alamanni were a group of Germanic tribes who lived near the Upper Rhine River during the first thousand years AD. A Roman historian named Cassius Dio first wrote about them around 213 AD, during the time of Emperor Caracalla.

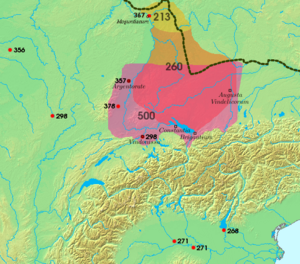

Around 260 AD, the Alemanni took control of a Roman area called the Agri Decumates. They later spread into what is now Alsace in France and northern Switzerland. This led to the development of the Old High German language in these areas. By the 700s, these regions were known as Alamannia.

In 496 AD, the Alemanni were defeated by the Frankish leader Clovis I at the battle of Tolbiac. They became part of his kingdom. Even though they were allies with the Christian Franks, the Alemanni still followed their old pagan religions. They slowly became Christian during the 600s. Their traditional laws from this time were written down in a book called the Lex Alamannorum.

For a while, the Franks had some power over Alemannia, but it wasn't very strong. However, after a rebellion led by Theudebald, Duke of Alamannia, a Frankish leader named Carloman had many Alemannic nobles killed. He then put Frankish dukes in charge.

Later, when the Carolingian Empire became weaker, the Alemannic counts (local rulers) became almost independent. They often argued for power with the Bishopric of Constance. A powerful family, the counts of Raetia Curiensis, were important in Alamannia. One of them, Burchard II, created the Duchy of Swabia. This duchy was recognized by Henry the Fowler in 919 AD and became a major part of the Holy Roman Empire.

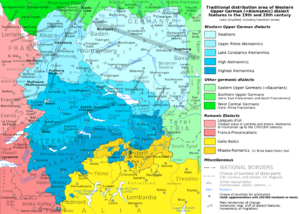

The areas where the Alemanni settled are still places where Alemannic German dialects are spoken today. These include parts of Germany (like Swabia and Baden), Alsace in France, German-speaking Switzerland, Liechtenstein, and Vorarlberg in Austria. The French name for Germany, Allemagne, comes from the Alemanni. Many other languages, like Spanish (Alemania), Portuguese (Alemanha), and Turkish (Almanya), also use names for Germany that come from the Alemanni.

Contents

What Does the Name Alemanni Mean?

According to an old historian named Gaius Asinius Quadratus, the name Alamanni means "all men." This suggests that they were a mix of different Germanic tribes. The Romans and Greeks called them this because they saw them as a group made up of people from many different groups in the region. This idea about the name is still widely accepted today.

Some people have suggested another idea: that the name comes from an old word *alah meaning "sanctuary."

In the 800s, Walafrid Strabo noted that only foreigners called the people of Switzerland and nearby areas "Alemanni." The people themselves used the name Suebi.

When Did the Alemanni First Appear?

Early Roman writers did not mention the Alemanni, suggesting they might not have existed as a distinct group yet. For example, Tacitus did not mention them in his book Germania (written around 90 AD). He described the area between the Rhine, Main, and Danube rivers as the Agri Decumates.

The Alemanni were first mentioned by Cassius Dio in 213 AD. He wrote about them during a military campaign by the Roman Emperor Caracalla. At that time, they seemed to live in the area of the Main River, south of another tribe called the Chatti.

Cassius Dio wrote that Emperor Caracalla treated the Alemanni badly. They had asked for his help, but instead, he took over their land, changed their place names, and killed their warriors. The Alemanni believed they had put a curse on Caracalla when he became ill.

In response, Caracalla attacked the Alemanni with his army, the Legio II Traiana Fortis. The Alemanni lost and were peaceful for a while. Caracalla even took the name Alemannicus.

Caracalla was known for his sudden and often unfair attacks. Whether the Alemanni were neutral before, Caracalla's actions made them strong enemies of Rome. Roman writers often called the Alemanni "barbari," meaning "savages." However, archaeological finds show that the Alemanni were quite Romanized. They lived in Roman-style houses and used Roman goods. Alemannic women even adopted Roman fashion earlier than the men.

Most of the Alemanni probably lived near the borders of Germania Superior at that time. Another historian, Ammianus Marcellinus, used the name Alemanni to describe Germans living near the Limes Germanicus (Roman border defenses) around 98-99 AD. This was when the border was first being fortified.

Ammianus also wrote that much later, Emperor Julian led an attack against the Alemanni, who were then in Alsace. He entered a forest where the paths were blocked by felled trees. Julian's army then reoccupied a "fortification which was founded on the soil of the Alemanni that Trajan wished to be called with his own name." This shows that Ammianus believed the Alemanni were the same people who had been in the region during Caracalla's time.

Conflicts with the Roman Empire

The Alemanni were often fighting with the Roman Empire in the 200s and 300s AD. In 268 AD, they launched a big invasion of Gaul (modern France) and northern Italy. This happened when the Romans had to move many of their soldiers from the German border to fight the Goths from the east.

Their raids caused a lot of damage. Gregory of Tours, a historian from the 500s, wrote about their destructive power. He mentioned a "king" named Chrocus who, with his mother's advice, "overran the whole of the Gauls, and destroyed from their foundations all the temples which had been built in ancient times." This shows how much destruction was blamed on the Alemanni by people living centuries later.

In the summer of 268 AD, Emperor Gallienus stopped the Alemanni from advancing into Italy. But then he had to deal with the Goths. After the Romans won against the Goths, Gallienus's successor, Claudius Gothicus, turned north to fight the Alemanni. They were spreading across all of Italy north of the Po River.

After attempts to make them leave peacefully failed, Claudius forced the Alemanni to fight at the Battle of Lake Benacus in November. The Alemanni were completely defeated and forced back into Germany. They did not threaten Roman territory for many years after this.

Their most famous battle against Rome happened in Argentoratum (Strasbourg) in 357 AD. There, they were defeated by Julian, who later became a Roman Emperor. Their king, Chnodomarius, was captured and taken to Rome.

On January 2, 366 AD, the Alemanni crossed the frozen Rhine River again in large numbers to invade Gaul. This time, they were defeated by Emperor Valentinian I (see Battle of Solicinium). In the big invasion of 406 AD, the Alemanni seem to have crossed the Rhine one last time. They conquered and then settled in what is now Alsace and a large part of the Swiss Plateau.

Key Battles Between Romans and Alemanni

Here are some important battles between the Romans and the Alemanni:

- 259: Battle of Mediolanum – Emperor Gallienus defeats the Alemanni to protect Rome.

- 268: Battle of Lake Benacus – Romans under Emperor Claudius II defeat the Alemanni.

- 271:

- Battle of Placentia – Emperor Aurelian is defeated by Alemanni forces invading Italy.

- Battle of Fano – Aurelian defeats the Alemanni, who start to retreat from Italy.

- Battle of Pavia – Aurelian destroys the retreating Alemanni army.

- 298:

- Battle of Lingones – Caesar Constantius Chlorus defeats the Alemanni.

- Battle of Vindonissa – Constantius defeats the Alemanni again.

- 356: Battle of Reims – Caesar Julian is defeated by the Alemanni.

- 357: Battle of Strasbourg – Julian drives the Alemanni out of the Rhineland.

- 368: Battle of Solicinium – Romans under Emperor Valentinian I defeat an Alemanni attack.

- 378: Battle of Argentovaria – Western Emperor Gratianus wins a victory over the Alemanni.

- 451: Battle of the Catalaunian Fields – Roman General Aetius and his allies defeat Attila's army, which included the Alemanni.

- 457: Battle of Campi Cannini – Alemanni invade Italy and are defeated near Lake Maggiore by Majorian.

- 554: Battle of the Volturnus – Byzantine General Narses defeats a combined force of Franks and Alemanni in southern Italy.

The Franks Take Control

The Alemannic kingdom, located between Strasbourg and Augsburg, lasted until 496 AD. That year, the Alemanni were conquered by Clovis I at the Battle of Tolbiac. This war is linked to Clovis's conversion to Christianity. After their defeat in 496, the Alemanni tried to break free from Frankish rule. They sought protection from Theodoric the Great of the Ostrogoths. However, after Theodoric's death, the Franks under Theudebert I again took control of them in 536 AD. From then on, the Alemanni were part of the Frankish kingdom and were ruled by a Frankish duke.

In 746 AD, Carloman stopped an uprising by executing many Alemannic nobles at the blood court at Cannstatt. For the next 100 years, Frankish dukes ruled Alemannia. After the treaty of Verdun in 843 AD, Alemannia became a province of the eastern kingdom of Louis the German. This kingdom was a early version of the Holy Roman Empire. The Duchy of Alemannia continued to exist until 1268 AD.

Alemannic Culture

Language

The German spoken today in the areas where the Alemanni once lived is called Alemannic German. It is one of the main groups of the High German languages. Early writings in Alemannic, like those on the Pforzen buckle, are some of the oldest examples of Old High German.

The High German consonant shift, a change in how certain sounds were pronounced, is thought to have started around the 400s AD. It might have begun in Alemannia or among the Lombards. Before this, the dialect spoken by the Alemanni was very similar to that of other West Germanic peoples.

Alamannia lost its separate identity when Charles Martel made it part of the Frankish empire in the early 700s. Today, "Alemannic" is mainly a term for language. It refers to Alemannic German, which includes dialects spoken in the southern parts of Baden-Württemberg and western Bavaria (German states), Vorarlberg (Austrian state), Swiss German in Switzerland, and the Alsatian language in Alsace (France).

Political Organization

The Alemanni created several areas called pagi (similar to cantons) on the east side of the Rhine River. We don't know the exact number or size of these pagi, and they likely changed over time.

These pagi, often in pairs, formed kingdoms (regna). It is believed these kingdoms were permanent and passed down through families. Ammianus described Alemannic rulers using different terms: reges excelsiores ante alios ("paramount kings"), reges proximi ("neighbouring kings"), reguli ("petty kings"), and regales ("princes"). This might have been a formal ranking system, or just general terms. In 357 AD, there seem to have been two main kings (Chnodomar and Westralp) who probably led the whole group. There were also seven other kings. Their territories were small and mostly located along the Rhine. It's possible that the reguli were the rulers of the two pagi within each kingdom.

Below the royal class were the nobles (called optimates by the Romans) and warriors (called armati by the Romans). The warriors included professional fighters and free men who were called to fight. Each nobleman could gather about 50 warriors.

Religion

The Alemanni became Christian during the Merovingian period (from the 500s to the 700s). In the 500s, most Alemanni were pagan, but by the 700s, most were Christian. The 600s were a time when Christian ideas and symbols slowly became more important.

Some historians think that certain Alemannic leaders, like King Gibuld, might have become Arian Christians as early as the late 400s, possibly influenced by the Visigoths.

In the mid-500s, the Byzantine historian Agathias wrote about the Alemanni fighting with Frankish troops. He noted that the Alemanni were like the Franks in every way except religion. He said they "worship certain trees, the waters of rivers, hills and mountain valleys, in whose honour they sacrifice horses, cattle and countless other animals by beheading them."

Agathias also mentioned that the Alemanni were especially harsh in destroying Christian holy places and robbing churches. The Franks, however, were respectful of these places. Agathias hoped that the Alemanni would learn better ways from being around the Franks, which eventually happened.

Important missionaries to the Alemanni were Columbanus and his student Saint Gall. Jonas of Bobbio wrote that Columbanus was active in Bregenz. There, he stopped a beer sacrifice to Wodan, a pagan god. Despite these efforts, the Alemanni seemed to continue their pagan practices for some time, mixing them with Christian elements. For example, their burial customs did not change, and warrior graves with mounds continued to be built throughout the Merovingian period.

Art from this time also shows a mix of traditional Germanic animal styles with Christian symbols. However, Christian symbols became more common during the 600s. Unlike the later Christianization of the Saxons, the Alemanni seemed to adopt Christianity slowly and willingly. They followed the example of the Merovingian leaders.

From about the 520s to the 620s, there was a rise in Alemannic Elder Futhark inscriptions (runic writings). About 70 examples have been found, mostly on brooches, belt buckles (like the Pforzen buckle and Bülach fibula), and other jewelry or weapon parts. The use of runes decreased as Christianity spread.

The Nordendorf fibula (early 600s) clearly mentions pagan gods: logaþorewodanwigiþonar, which can be read as "Wodan and Donar are magicians/sorcerers." This could be a pagan prayer or a Christian charm against these gods.

A runic inscription on a fibula found at Bad Ems shows Christian religious feelings. It even has a Christian cross. It reads god fura dih deofile ᛭ ("God for/before you, Theophilus!", or "God before you, Devil!"). This inscription, from between 660 and 690 AD, marks the end of the Alemannic tradition of writing with runes. Bad Ems is on the edge of the Alemannic settlement area, where Frankish influence would have been strongest.

The exact date when the bishopric of Konstanz was established is not known. It might have been founded by Columbanus himself before 612 AD. It definitely existed by 635 AD, when Gunzo appointed John of Grab as bishop. Constance was a missionary bishopric in newly converted lands. It did not have a long history like the older bishoprics of Chur (established 451 AD) and Basel (an episcopal seat from 740 AD). The church becoming an institution recognized by rulers is also seen in their laws. The early 600s Pactus Alamannorum hardly mentions the church's special rights. But Lantfrid's Lex Alamannorum from 720 AD has a whole chapter just for church matters.

Genetics

A scientific study published in Science Advances in September 2018 looked at the remains of eight people buried in a 600s Alemannic graveyard in Niederstotzingen, Germany. This is the most complete Alemannic graveyard ever found. The highest-ranking person in the graveyard was a male with Frankish grave goods. Four males were found to be closely related to him. They all carried a specific type of paternal haplogroup R1b1a2a1a1c2b2b. A sixth male carried a different paternal haplogroup and a maternal haplogroup U5a1a1. Along with the five related individuals, he showed close genetic links to northern and eastern Europe, especially Lithuania and Iceland. Two other people buried at the cemetery were genetically different from the others and from each other. They showed genetic links to Southern Europe, especially northern Italy and Spain. These two, along with the sixth male, might have been adopted or slaves.

See also

In Spanish: Pueblo alamán para niños

In Spanish: Pueblo alamán para niños

- Annales Alamannici

- List of rulers of Alamannia

- List of confederations of Germanic tribes

- Armalausi

- Varisci

- Helvetii

- Charietto

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |