Attila facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Attila |

|

|---|---|

King Attila (Chronicon Pictum, 1358)

|

|

| King and chieftain of the Hunnic Empire | |

| Reign | 434–453 |

| Predecessor | Bleda and Ruga |

| Successor | Ellac, Dengizich, Ernak |

| Born | Unknown date, c. 406 |

| Died | c. March 453 (aged 46–47) |

| Spouse | Kreka and Ildico |

| Father | Mundzuk |

Attila (around 406–453 AD), often called Attila the Hun, was a powerful ruler of the Huns. He led his people from 434 until his death in 453. Attila also ruled over a large empire of different tribes, including Huns, Ostrogoths, Alans, and Bulgars, across Central and Eastern Europe.

During his time, Attila was one of the most feared enemies of the Western and Eastern Roman Empires. He led his armies across the Danube river twice, attacking and taking valuable goods from the Balkans. However, he could not capture the great city of Constantinople. After a campaign in Persia that wasn't successful, he invaded the Eastern Roman Empire in 441. This success made him brave enough to invade the Western Roman Empire. In 451, he tried to conquer Roman Gaul (which is modern France). He crossed the Rhine river and marched towards Aurelianum (Orléans), but he was stopped at the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains.

Later, Attila invaded Italy, causing a lot of damage in the northern areas. But he was unable to capture Rome. He planned more attacks against the Romans, but he died in 453. After Attila's death, his empire quickly fell apart. Attila is still remembered as an important figure in Germanic heroic legend.

Contents

- What Does the Name Attila Mean?

- How Do We Know About Attila?

- Attila's Early Life and the Huns

- Attila Becomes King

- Attila's Campaigns Against the Eastern Roman Empire

- Attila's Rule and Later Campaigns

- Attila in the West

- Invasion of Italy and Attila's Death

- What Did Attila Look Like?

- Attila in Stories and Art

- Depictions of Attila

- See also

What Does the Name Attila Mean?

Many experts believe the name Attila comes from an old Germanic language. It might be formed from the Gothic word atta, meaning "father," with a small ending -ila. This would make his name mean "little father."

Other scholars think the name might have come from a Turkic language. Some ideas suggest it could mean "the oceanic, universal ruler" or be related to "horseman" or "horse." It's possible that Attila's name was not originally Hunnic, just as many kings throughout history have names from other cultures.

How Do We Know About Attila?

Learning about Attila is tricky because most of the information we have comes from his enemies, the Greeks and Romans. They wrote about him in Greek and Latin.

- Priscus: He was a Byzantine diplomat and historian who actually visited Attila's court in 449. He wrote down what he saw and heard. Even though he was on the Roman side, his writings are a very important source. He is the only person known to have described what Attila looked like.

- Jordanes: A historian from the 6th century who used Priscus's work a lot. His book, The Origin and Deeds of the Goths, tells us a lot about the Hunnic Empire.

- Other Writings: Some church writings also mention Attila, but they can be hard to check.

- Oral History: The Huns themselves passed down their stories through songs and poems. Bits of these stories later appeared in Scandinavian and German legends.

- Archaeology: Digging up old sites has helped us learn about the Huns' way of life and how they fought. However, Attila's tomb and the location of his capital city have not been found yet.

Attila's Early Life and the Huns

The Huns were a group of Eurasian nomads. They came from east of the Volga River around 370 AD and built a huge empire in Europe. They were amazing horsemen and archers, known for their speed and skill in battle. The Huns were a society of warriors who mostly ate meat and milk from their herds.

The Huns' exact origin and language are still debated. Some theories suggest their leaders might have spoken a Turkic language. Attila's father, Mundzuk, was the brother of two Hunnic kings, Octar and Ruga. This means Attila came from a noble family. Historians believe Attila was born around 406 AD.

Attila grew up in a world that was changing very fast. The Huns had only recently arrived in Europe. They crossed the Volga river in the 370s and took over the land of the Alans. Then they attacked the Gothic kingdom. The Huns were so powerful that many Germanic tribes fled into the Roman Empire to escape them.

The Roman Empire had been split into two parts since 395 AD: the Western Roman Empire (based in Ravenna) and the Eastern Roman Empire (based in Constantinople). Even though the Huns caused problems for the Romans by pushing other tribes into their lands, the Romans and Huns often had friendly relations. The Romans even hired Huns as soldiers to fight against other Germanic tribes. By the time Attila was growing up, the Huns had become a major power.

Attila Becomes King

When Attila's uncle, Ruga, died in 434 AD, Attila and his brother Bleda became the joint rulers of the Hunnic tribes. At this time, the Huns were talking with the Eastern Roman Emperor Theodosius II about some Huns who had run away and found safety in the Eastern Roman Empire.

The next year, Attila and Bleda met with Roman officials. They sat on horseback, as was the Hunnic custom. They agreed to a very good deal for the Huns, called the Treaty of Margus. The Romans agreed to:

- Send back the Huns who had run away.

- Double the amount of gold they paid the Huns each year (from about 115 kg to 230 kg).

- Open their markets for Hunnic traders.

- Pay a ransom for each Roman prisoner taken by the Huns.

After this treaty, the Huns went back to their home in the Great Hungarian Plain. Theodosius used this time to make the walls of Constantinople stronger and improve his defenses along the Danube river.

Attila's Campaigns Against the Eastern Roman Empire

The Huns stayed away from the Romans for a few years, trying to invade the Sassanid Empire (Persia). But they were defeated there and turned their attention back to Europe. In 440, they returned to the Roman borders. They attacked traders and cities along the Danube river, including Margus and Viminacium.

While the Huns were attacking, the Vandals (another Germanic tribe) captured the rich Roman province of Africa. This made it harder for Rome to get food. The Romans had to move their soldiers from the Balkans to Sicily to fight the Vandals. This left the way open for Attila and Bleda to invade the Balkans in 441. They attacked many cities, including Singidunum (Belgrade) and Sirmium.

In 442, Emperor Theodosius brought his troops back from Sicily. He also made new coins to pay for the war against the Huns. Attila responded with another campaign in 443. This time, his army had new weapons like battering rams and rolling siege towers. They used these to attack cities like Ratiara and Naissus (Niš), killing many people.

The Huns continued their advance, taking more cities and defeating Roman armies. They reached Constantinople, but the city's strong double walls stopped them. Theodosius realized he couldn't win. He sent an official to negotiate peace. The new peace terms were much harsher:

- The Romans had to pay 2,000 kg of gold as punishment.

- The yearly payment to the Huns was tripled to about 700 kg of gold.

- The ransom for each Roman prisoner increased.

After these demands were met, the Hun kings went back to their empire. Around 445, Attila's brother Bleda died. Attila then became the sole ruler of the Huns.

Attila's Rule and Later Campaigns

In 447, Attila again attacked the Eastern Roman Empire. His army fought and defeated a Roman army in the Battle of the Utus, though the Huns also suffered heavy losses. The Huns then swept through the Balkans, reaching as far as Thermopylae. Constantinople was saved because its walls had been rebuilt and strengthened after earlier earthquakes.

Attila in the West

In 450, Attila announced he would attack the Visigoths in Toulouse. He had been on good terms with the Western Roman Empire and its powerful general Flavius Aetius. Aëtius had even lived among the Huns for a short time.

However, Emperor Valentinian III's sister, Honoria, sent Attila a plea for help and her engagement ring. She wanted to avoid being forced to marry a Roman senator. Attila saw this as a marriage proposal and demanded half of the Western Roman Empire as her dowry. Valentinian was furious and denied the marriage. Attila then sent an envoy to say Honoria was innocent and he would come to claim what was his.

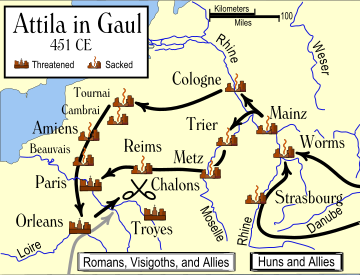

Attila also got involved in a dispute over who should rule the Franks. He supported one son, while Aëtius supported another. Attila gathered his many allied tribes, including the Gepids, Ostrogoths, and Burgundians, and began his march west. In 451, he reached Belgica (modern Belgium and parts of France) with a huge army.

He captured the city of Metz on April 7. Other cities like Reims and Troyes were also attacked or threatened. Aëtius moved to stop Attila, gathering troops from the Franks, Burgundians, and Celts. The Visigoth king Theodoric I also agreed to join the Romans. Their combined armies reached Orléans before Attila, stopping his advance. Aëtius then chased the Huns and caught them near Catalaunum (modern Châlons-en-Champagne).

The two armies fought in the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains. This battle is often seen as a victory for the Roman-Visigothic alliance. King Theodoric was killed in the fighting. Aëtius did not press his advantage, perhaps because he didn't want the Visigoths to become too powerful.

Invasion of Italy and Attila's Death

In 452, Attila returned to Italy to push his marriage claim with Honoria. He attacked and destroyed many cities in northern Italy. The city of Aquileia was so completely ruined that it was hard to find its original site afterwards. Many people fled to small islands in the Venetian Lagoon, which later became the city of Venice. Aëtius didn't have enough soldiers to fight a big battle, but he managed to slow Attila down.

Attila finally stopped at the River Po. His army might have been weakened by disease and lack of food. Emperor Valentinian III sent three envoys, including Pope Leo I, to meet Attila. They met at Mincio and convinced Attila to leave Italy and negotiate peace. Some accounts say Pope Leo's presence, along with a fear of what happened to Alaric I (who died soon after sacking Rome in 410), made Attila pause. Italy was also suffering from a terrible famine, so there wasn't much food for Attila's army.

Also, an Eastern Roman force had crossed the Danube and defeated the Huns who were left behind to protect their lands. Facing these problems, Attila decided to leave Italy.

Attila's Death

After leaving Italy, Attila planned to attack Constantinople again because the new Eastern Roman Emperor, Marcian, had stopped paying tribute to the Huns. However, Attila died suddenly in early 453.

The most common story, from Priscus, says that Attila was celebrating his newest marriage to a young woman named Ildico. During the celebration, he suffered severe bleeding and died. He may have had a nosebleed and choked, or he might have had internal bleeding.

Another story, written later, says that Attila was killed by his wife. However, most historians believe the account from Priscus, which says he died naturally.

After his death, Attila's body was placed in a silk tent. His best horsemen rode around it in circles, singing about his brave deeds. They buried his body secretly at night in three coffins: one of gold, one of silver, and one of iron. They also buried treasures and weapons with him. To keep the burial place a secret, those who buried him were also killed.

What Happened After Attila?

Attila's sons, Ellac, Dengizich, and Ernak, tried to rule the empire together. But they argued and quickly destroyed their father's empire. A Germanic alliance, led by the Gepid ruler Ardaric, rebelled against Hunnic rule. They fought the Huns in the Battle of Nedao in 454 AD, where Attila's oldest son, Ellac, was killed.

Attila's other sons tried to fight the Goths but were pushed back. The Hunnic empire soon ended. While many people claim to be descendants of Attila, there is no clear proof.

What Did Attila Look Like?

We don't have a direct description of Attila from someone who saw him. But the historian Jordanes wrote down what Priscus might have said: "He was a man born to shake the nations, the scourge of all lands. He terrified everyone with the dreadful rumors about him. He walked proudly, looking around, showing his strong spirit in his movements. He loved war but was careful in his actions. He was wise in his plans, kind to those who asked for help, and gentle to those he protected. He was short, with a broad chest and a large head. His eyes were small, his beard thin and gray, and he had a flat nose and dark skin, showing where he came from."

Some scholars think these features sound like people from East Asia, suggesting Attila's ancestors might have come from there.

Attila in Stories and Art

Attila's name has many different forms in different languages, like Atli in Old Norse, Etzel in German, and Etele in Hungarian.

Legends About Attila and the Sword of Mars

Jordanes wrote that Attila had the "Holy War Sword of the Scythians", which was given to him by the god Mars. This sword supposedly made him a "prince of the entire world."

Later, in the 12th century, the royal court of Hungary claimed they were related to Attila. A sword believed to be Attila's sword was given to a German duke. This sword, which is now in a museum in Vienna, looks like it was made by Hungarian goldsmiths much later, around the 9th or 10th century.

Legends About Attila and Pope Leo I

A medieval story says that when Pope Leo met Attila, Saint Peter and Saint Paul also appeared. This miraculous story was popular at the time. Later, famous artists like Raphael and Alessandro Algardi created artworks showing this meeting.

One version of this story says that the Pope promised Attila that if he left Rome in peace, one of Attila's successors would receive a holy crown. This is thought to refer to the Holy Crown of Hungary.

Attila in Germanic Heroic Legends

Some old stories describe Attila as a great and noble king. He appears in several Norse texts, like Atlakviða and Volsunga saga. In German legends, Attila (called Etzel) is a powerful king who gives shelter to the hero Dietrich von Bern. Attila also appears in the famous German epic Nibelungenlied, where he is the second husband of Kriemhild.

Depictions of Attila

-

The Meeting of Leo I

and Attila

by Alessandro Algardi

(1646–1653) -

Attila portrayed by Anthony Quinn in Attila

-

Attila statue in Nibelungs fountain (Austria, Tulln)

-

Attila statue in Nibelungs fountain (Austria, Tulln)

See also

In Spanish: Atila para niños

In Spanish: Atila para niños

- Onegesius

- Bleda

- Mundzuk