Battle of Tours facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Tours |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Umayyad invasion of Gaul | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Umayyad Caliphate | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Abd al-Rahman al-Ghafiqi † | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 15,000–20,000 | 20,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1,000 | 12,000 | ||||||

The Battle of Tours, also known as the Battle of Poitiers, was a very important fight that happened on October 10, 732. It was a key moment during the Umayyad invasion of Gaul (which is modern-day France). In this battle, the Frankish and Aquitanian armies, led by a strong leader named Charles Martel, won against the invading Umayyad forces. The Umayyad army was led by Abd al-Rahman al-Ghafiqi, who was the governor of al-Andalus (parts of Spain and Portugal).

Many historians believe this Christian victory was super important. It helped stop the spread of Islam into Western Europe. The exact details of the battle, like how many soldiers fought or where it happened, are not perfectly clear. However, most old writings agree that the Umayyads had more soldiers but lost many more lives.

The Frankish soldiers fought bravely, even though they didn't have heavy cavalry (soldiers on horseback with strong armor). The battle took place somewhere between the cities of Poitiers and Tours in western France. This area was near the border of the Frankish kingdom and the independent Duchy of Aquitaine, which was ruled by Odo the Great.

Abd al-Rahman al-Ghafiqi was killed during the battle. After this, the Umayyad army left the area. This victory helped set the stage for the Carolingian Empire and made the Franks a very powerful force in western Europe for the next 100 years. Many historians agree that the Franks becoming strong in western Europe shaped the future of the entire continent. The Battle of Tours helped confirm their power.

Contents

Why Did the Battle of Tours Happen?

The Battle of Tours happened after about 20 years of Umayyad conquests in Europe. These conquests started in 711 when they invaded the Christian Visigothic Kingdom in the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal). After that, they moved into the Frankish lands of Gaul, which used to be part of the Roman Empire.

The Umayyad military campaigns pushed north into Aquitaine and Burgundy. They had a big fight at Bordeaux and raided a city called Autun. Charles Martel's victory is widely seen as the event that stopped the Umayyad forces from moving further north from Spain. It also helped prevent Western Europe from becoming Islamic.

Where Did the Armies Meet?

Most historians think the two armies met near where the rivers Clain and Vienne join, between Tours and Poitiers. We don't know the exact number of soldiers in each army. An old Latin source, the Mozarabic Chronicle of 754, says the Frankish forces were "greater in number of soldiers and formidably armed." This source also says they killed the Umayyad leader, Abd al-Rahman. Some Arab and Muslim historians agree with this.

However, most Western sources disagree. They estimate the Franks had about 30,000 soldiers, which was less than half of the Muslim force. Modern historians try to estimate troop numbers based on how much food and supplies the land could support. They believe the total Muslim force might have been larger if you count all their raiding groups.

Some estimates for the Umayyad army range from 20,000 to 80,000 soldiers. For the Franks, estimates are usually between 15,000 and 30,000. It's hard to know for sure, but many experts think both armies were probably around 20,000 to 30,000 men.

We also don't know how many soldiers died in the battle. Later writers claimed Charles Martel's army lost about 1,500 men, while the Umayyad force supposedly lost a huge number, up to 375,000. However, these very high numbers were also used for another battle, the Battle of Toulouse (721). So, it's likely these numbers are exaggerated.

Who Were the Umayyads?

The Umayyad dynasty was the first major ruling family of the Islamic empire after the first four caliphs. At the time of the Battle of Tours, the Umayyad Caliphate was probably the strongest military power in the world. They had expanded their empire greatly, conquering lands across Persia (modern-day Iran) and North Africa.

Their empire was huge and included many different peoples. They had defeated the Sasanian Empire completely and taken over much of the Byzantine Empire, including Syria, Armenia, and North Africa.

Who Were the Franks?

The Frankish realm under Charles Martel was the leading military power in western Europe. Charles Martel was like the commander-in-chief of the Franks. His kingdom included northern and eastern France, most of western Germany, and the Low Countries (Luxembourg, Belgium, and the Netherlands). This area was starting to become the first real empire in western Europe since the fall of Rome.

However, the Franks still had to fight against groups like the Saxons and Frisians. They also faced opponents like the Basque-Aquitanians, led by Odo the Great, Duke of Aquitaine.

Umayyad Expansion from Spain

The Umayyad troops, led by Al-Samh ibn Malik al-Khawlani, who was the governor of al-Andalus, took over Septimania (a region in southern France) by 719. They had already swept through the Iberian Peninsula. Al-Samh made Narbonne his capital in 720. The Moors (another name for the Umayyads from Spain) called it Arbūna.

With Narbonne's port secured, the Umayyads quickly took over other cities like Alet, Béziers, Agde, and Nîmes. These cities were still controlled by Visigothic counts.

The Umayyad campaign into Aquitaine faced a small problem at the Battle of Toulouse. Duke Odo the Great surprised Al-Samh ibn Malik's forces and broke their siege of Toulouse. Al-Samh ibn Malik was badly wounded and died. But this defeat didn't stop the Umayyads. They continued to raid old Roman Gaul, striking as far as Autun in Burgundy by 725.

Odo was threatened by the Umayyads from the south and the Franks from the north. In 730, he made an alliance with a Berber commander named Uthman ibn Naissa (called "Munuza" by the Franks). To make the alliance strong, Odo gave his daughter Lampagie to Uthman in marriage. The Moors then stopped their raids across the Pyrenees mountains, which was Odo's southern border.

However, the next year, Uthman broke away from his Arab leaders. Abd al-Rahman then sent an army to crush Uthman's revolt. After that, he turned his attention to Odo, Uthman's ally.

Odo gathered his army at Bordeaux, but he was defeated, and Bordeaux was looted. During the next fight, the Battle of the River Garonne, an old writing said, "God alone knows the number of the slain." It also said the Umayyads "plundered far into the country of the Franks, and smote all with the sword." When Odo fought them at the Garonne River, he had to flee.

Odo Asks the Franks for Help

Even after his big losses, Odo started to get his troops ready again. He warned the Frankish leader, Charles Martel, about the danger to his kingdom. Odo asked the Franks for help. Charles Martel only agreed to help after Odo promised to accept Frankish rule.

It seems the Umayyads didn't know how strong the Franks really were. The Umayyad forces weren't very worried about any of the Germanic tribes, including the Franks. Arab writings from that time show that they only realized the Franks were a growing military power after the Battle of Tours.

Also, the Umayyads probably didn't scout north to look for enemies. If they had, they would have seen Charles Martel as a powerful leader. He had been gaining control over much of Europe since 717.

Umayyad March Towards the Loire River

In 732, the Umayyad army was moving north towards the Loire River. They had moved faster than their supply wagons and a large part of their army. They had easily destroyed all resistance in that part of Gaul. The invading army had split into several raiding groups, while the main army moved more slowly.

The Umayyads probably delayed their campaign until late in the year. This was because their army needed to find food as they moved. They had to wait until the area's wheat harvest was ready and stored.

Odo was defeated so easily at Bordeaux and Garonne, even though he had won at the Battle of Toulouse eleven years earlier. At Toulouse, he had surprised an overconfident enemy. The Umayyad forces there were mostly foot soldiers, and their cavalry wasn't used. At Bordeaux and Garonne, the Umayyad forces were mostly cavalry and were able to fight well. This led to Odo's army being destroyed.

Odo's soldiers, like other European troops at that time, did not have stirrups. This meant they didn't have heavy cavalry. Most of their soldiers were foot soldiers. The Umayyad heavy cavalry broke Odo's foot soldiers in their first attack and then killed them as they ran away.

The invading force then went on to destroy southern Gaul. One possible reason for their advance, according to an old Frankish writing, was the riches of the Abbey of Saint Martin of Tours. This was the most famous and holy place in western Europe at the time. When Charles Martel, the Frankish leader, heard about this, he got his army ready. He marched south, avoiding the old Roman roads, hoping to surprise the Muslims.

The Battle (October 732)

Getting Ready and Moving Troops

Everyone agrees that the invading Umayyad forces were surprised to find a large army right in their path to Tours. Charles Martel had achieved the surprise he wanted. He then chose not to attack right away. Instead, he set up a strong defensive formation, like a phalanx (a tight wall of soldiers). Arab sources say the Franks formed a big square, using hills and trees in front of them to slow down or break up the Muslim cavalry charges.

For one week, the two armies had small fights. The Umayyads waited for all their soldiers to arrive. Abd al-Rahman, even though he was a skilled commander, had been outsmarted. Charles had managed to bring his forces together and choose the battlefield. Also, the Umayyads couldn't tell how big Charles's army was because he used the forest to hide his true numbers.

Charles's foot soldiers were his best chance for victory. They were experienced and tough, and most had fought under him for years. Some had been with him since 717. Besides his main army, he also had local militias. These militias were mostly used for gathering food and bothering the Muslim army.

Many historians have thought that the Franks were outnumbered by at least two to one at the start of the battle. However, some sources, like the Mozarabic Chronicle of 754, say this wasn't true.

Charles correctly guessed that Abd al-Rahman would feel forced to fight. He knew Abd al-Rahman would want to move on and loot Tours. Neither side wanted to attack first. Abd al-Rahman felt he had to sack Tours, which meant he had to go through the Frankish army on the hill. Charles's choice to stay on the hills was very important. It forced the Umayyad cavalry to charge uphill and through trees, which made their attacks less effective.

Charles had been getting ready for this fight since the Battle of Toulouse ten years earlier. Historians like Gibbon believe Charles made the best of a difficult situation. Even though he was supposedly outnumbered and had no heavy cavalry, he had strong, experienced foot soldiers who trusted him completely. In the Middle Ages, there were usually no permanent armies in Europe. But Charles even took a large loan from the Pope. He convinced the Pope of the danger and used the money to properly train and keep a full-size army, mostly made of professional foot soldiers. These soldiers were also heavily armed.

Formed into a phalanx, they could stand up to a cavalry charge better than expected. This was especially true because Charles had the high ground, with trees in front to further stop cavalry charges. The Arab spies failed because they didn't know how good Charles's forces were. He had trained them for ten years. And while he knew the Caliphate's strengths and weaknesses, he knew they knew nothing about the Franks.

Also, the Franks were dressed for the cold weather. The Arabs wore very light clothing, which was better for North African winters than European winters.

The battle became a waiting game. The Muslims didn't want to attack an army that might be bigger than theirs. They wanted the Franks to come out into the open. The Franks stayed in a strong defensive formation and waited for the Muslims to charge uphill. The battle finally began on the seventh day. Abd al-Rahman didn't want to wait any longer, as winter was coming.

The Fight Begins

Abd al-Rahman trusted his cavalry's fighting skills. He had them charge repeatedly throughout the day. The disciplined Frankish soldiers held strong against the attacks. Arab sources say the Arab cavalry broke into the Frankish square several times. But even then, the Franks did not break apart. These well-trained Frankish soldiers did something that was thought impossible at the time: foot soldiers holding their ground against a heavy cavalry charge. Paul Davis says the main part of Charles's army was professional foot soldiers who were very disciplined and motivated. They had fought with him all over Europe.

What People Wrote at the Time

The Mozarabic Chronicle of 754 "describes the battle in more detail than any other Latin or Arabic source." It says about the battle:

While Abd ar-Rahman was chasing Odo, he decided to destroy Tours by burning its churches. There he met the leader of Austrasia named Charles. Charles was a warrior from his youth and an expert in military matters. Odo had called him for help. After each side bothered the other with raids for almost seven days, they finally got ready to fight fiercely. The northern people stood as still as a wall, holding together like a glacier in the cold. In a flash, they wiped out the Arabs with their swords. The people of Austrasia, with more soldiers and strong weapons, killed the king, Abd ar-Rahman. But suddenly, seeing the countless tents of the Arabs, the Franks put away their swords, putting off the fight until the next day because night had fallen. Rising from their camp at dawn, the Europeans saw the tents of the Arabs all arranged just as they had been the day before. Not knowing they were empty and thinking there were Saracen forces ready for battle, they sent officers to check. They found that all the Ishmaelite troops had left. They had indeed fled silently by night, returning to their own country.

Charles Martel's family wrote a summary of the battle for the Continuations of Fredegar's Chronicle:

Prince Charles bravely lined up his soldiers against them [the Arabs] and the warrior rushed at them. With Christ's help, he overturned their tents and hurried to battle to crush them in a great slaughter. King Abdirama was killed, he destroyed [them], driving forth the army, he fought and won. So the victor triumphed over his enemies.

This source also says that "he (Charles Martel) came down upon them like a great man of battle." It continues to say Charles "scattered them like the stubble."

It is thought that Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People mentions the Battle of Tours: "...a terrible plague of Saracens destroyed France with awful killing, but they not long after in that country received the punishment they deserved."

Charles Martel's Victory

Umayyad Retreat and Later Invasions

The Umayyad army went back south over the Pyrenees mountains. Charles Martel continued to expand his power south in the years that followed. After Odo died around 735, Charles wanted to add Odo's duchy to his own lands. He went there to get the Aquitanians to accept his rule. But the nobles made Hunald, Odo's son, the new duke. Charles accepted this when the Umayyads entered Provence the next year as allies of Duke Maurontus.

Hunald, who at first didn't want to accept Charles as his overlord, soon had no choice. He recognized Charles as his ruler, though not for long, and Charles confirmed his duchy.

Later Umayyad Invasions (735–739)

In 735, Uqba ibn al-Hajjaj, the new governor of al-Andalus, invaded Gaul. Historians like Antonio Santosuosso say he moved into France to get revenge for the defeat at Tours and to spread Islam. According to Santosuosso, Uqba ibn al-Hajjaj converted about 2,000 Christians he had captured. In the last big attempt to invade Gaul through Spain, a large army gathered at Saragossa and entered what is now France in 735. They crossed the Rhone River and captured and looted Arles. From there, they went into the heart of Provence, finally capturing Avignon, despite strong resistance.

Uqba ibn al-Hajjaj's forces stayed in Septimania and part of Provence for four years. They raided places like Lyons, Burgundy, and Piedmont. Charles Martel invaded Septimania in 736 and 739, but he was forced back to his own Frankish territory. Alessandro Santosuosso believes this second Umayyad invasion was probably more dangerous than the first. The failure of this second invasion stopped any serious Muslim expeditions across the Pyrenees, though small raids continued. Plans for more large-scale attempts were stopped by internal problems within the Umayyad lands.

Moving Towards Narbonne

Even after the defeat at Tours, the Umayyads controlled parts of Septimania for another 27 years. However, they couldn't expand further. Earlier agreements with the local people remained strong. In 734, the governor of Narbonne, Yusuf ibn Abd al-Rahman al-Fihri, made agreements with several towns. These agreements were about defending together against Charles Martel, who was steadily bringing the south under his control. Charles conquered Umayyad forts and destroyed their soldiers at the Siege of Avignon and the Siege of Nîmes.

The army trying to help Narbonne met Charles in open battle at the Battle of the River Berre and was destroyed. However, Charles failed to take Narbonne at the Siege of Narbonne in 737. The city was defended by its Muslim Arab and Berber citizens, as well as its Christian Visigothic citizens.

The Carolingian Dynasty

Charles Martel didn't want to tie up his army for a siege that could last years. He also believed he couldn't afford the losses of a full-on attack like he used at Arles. So, Charles was happy to just isolate the few remaining invaders in Narbonne and Septimania. The threat of invasion lessened after the Umayyad defeat at Narbonne. The unified Caliphate would later fall apart in a civil war in 750 at the Battle of the Zab.

It was Charles's son, Pepin the Short, who finally forced Narbonne to surrender in 759. This brought it into the Frankish lands. The Umayyad dynasty was removed and driven back to Al-Andalus. There, Abd al-Rahman I set up an emirate (a smaller kingdom) in Córdoba, opposing the Abbasid caliph in Baghdad.

In northeastern Spain, the Frankish emperors created the Marca Hispanica across the Pyrenees (in part of what is now Catalonia). They recaptured Girona in 785 and Barcelona in 801. This created a buffer zone against Muslim lands across the Pyrenees. Historian J.M. Roberts said in 1993 about the Carolingian dynasty:

It produced Charles Martel, the soldier who turned the Arabs back at Tours, and the supporter of Saint Boniface the Evangelizer of Germany. This is a considerable double mark to have left on the history of Europe.

Before the Battle of Tours, stirrups (foot supports for riders) might have been unknown in the West. Some historians argue that using stirrups for cavalry directly led to the development of feudalism (a system of land ownership and loyalty) in the Frankish kingdom by Charles Martel and his family.

How Important Was the Battle of Tours?

Historians have different ideas about how important this battle was. Early Western historians, starting with the Mozarabic Chronicle of 754, emphasized how much the battle changed history. They claimed Charles had saved Christianity. Historians like Edward Gibbon in the 1700s agreed that the Battle of Tours was definitely a turning point in world history.

Modern historians are divided into two main groups. One group generally agrees with Gibbon, believing the battle was very important. The other group argues that the battle has been greatly exaggerated. They say it was just a raid, not a full invasion, and only a minor setback for the Caliph, not a huge defeat that ended Islamic expansion. However, it's important to note that even within the first group, many historians have a more balanced view. They see the battle as important, but they analyze it from military, cultural, and political angles, rather than just as a "Muslim versus Christian" fight.

In the East, Arab histories also changed over time. At first, the battle was seen as a terrible defeat. Then, it mostly disappeared from Arab histories. This has led to a modern debate about whether it was a second major loss after the Second Siege of Constantinople, or part of a series of big defeats that led to the fall of the first Caliphate. With the Byzantines, Bulgarians, and Franks all stopping further expansion, internal problems in the Umayyad lands grew. This led to the Great Berber Revolt of 740 and eventually the Battle of the Zab, which destroyed the Umayyad Caliphate.

What Some Historians Say About Its Importance

Victor Davis Hanson, a military historian, says that "most of the 18th and 19th century historians like Gibbon saw Tours as a landmark battle that marked the high tide of the Muslim advance into Europe." Leopold von Ranke felt that Tours-Poitiers "was the turning point of one of the most important periods in the history of the world."

William E. Watson writes that "the later history of the West would have gone very differently if 'Abd ar-Rahman had won at Tours-Poitiers in 732." He adds that "after looking at why the Muslims moved north of the Pyrenees, one can see the huge historical importance of the battle."

Victorian writer John Henry Haaren says in Famous Men of the Middle Ages: "The battle of Tours or Poitiers... is seen as one of the decisive battles of the world. It decided that Christians and not Muslims should be the ruling power in Europe." Bernard Grun, in his "Timetables of History," says: "In 732 Charles Martel's victory over the Arabs at the Battle of Tours stops their westward advance."

Historian Norman Cantor said in 1993: "It may be true that the Arabs had now fully used up their resources and they would not have conquered France, but their defeat (at Tours) in 732 put a stop to their advance to the North."

Military historian Robert W. Martin thinks Tours is "one of the most decisive battles in all of history." Also, historian Hugh Kennedy says "it was clearly important in making Charles Martel and the Carolingians powerful in France. But it also had big effects in Muslim Spain. It signaled the end of the ghanima (booty) economy."

Military Historian Paul Davis argued in 1999: "if the Muslims had won at Tours, it's hard to imagine what group in Europe could have organized to resist them." George Bruce, in his update of Harbottle's military history Dictionary of Battles, says that "Charles Martel defeated the Moslem army, effectively ending Moslem attempts to conquer western Europe."

Professor of religion Huston Smith says in The World's Religions: Our Great Wisdom Traditions: "But for their defeat by Charles Martel in the Battle of Tours in 732, the entire Western world might today be Muslim." Historian Robert Payne said: "The more powerful Muslims and the spread of Islam were knocking on Europe's door. And the spread of Islam was stopped along the road between the towns of Tours and Poitiers, France, with just its head in Europe."

Victor Davis Hanson has commented that:

Recent scholars have suggested [Tours-Poitiers], which was poorly recorded in old sources, was just a raid and therefore a made-up story by the West. Or that a Muslim victory might have been better than continued Frankish rule. What is clear is that [Tours-Poitiers] marked a general continuation of the successful defense of Europe (from the Muslims). After the victory at Tours, Charles Martel went on to clear southern France of Islamic attackers for decades. He united the fighting kingdoms into the beginnings of the Carolingian Empire, and made sure there were ready and reliable troops from local areas.

Paul Davis, another modern historian, says: "whether Charles Martel saved Europe for Christianity is debated. What is sure, however, is that his victory made sure the Franks would rule Gaul for more than a century." Davis writes, "Muslim defeat ended the Muslims' threat to western Europe, and Frankish victory made the Franks the dominant people in western Europe, setting up the dynasty that led to Charlemagne."

Why Some Historians Disagree About Its Importance

Other historians disagree with this idea. Alessandro Barbero writes: "Today, historians tend to play down the importance of the battle of [Tours-Poitiers]. They point out that the Muslim army defeated by Charles Martel didn't aim to conquer the Frankish kingdom. Their goal was simply to loot the rich monastery of St-Martin of Tours." Similarly, Tomaž Mastnak writes:

Modern historians have created a myth saying this victory saved Christian Europe from the Muslims. Edward Gibbon, for example, called Charles Martel the savior of Christendom and the battle near Poitiers an event that changed world history. ... This myth has lasted into our own times. ... However, people at the time of the battle did not overstate its importance. The writers who continued Fredegar's chronicle, who probably wrote in the mid-700s, saw the battle as just one of many military fights between Christians and Saracens. Also, it was just one in a series of wars fought by Frankish princes for treasure and land. ... One of Fredegar's continuators showed the battle of [Tours-Poitiers] for what it really was: an event in the struggle between Christian princes as the Carolingians tried to bring Aquitaine under their rule.

The historian Philip Khuri Hitti believes that "In reality, nothing was decided on the battlefield of Tours. The Muslim wave, already a thousand miles from where it started in Gibraltar – not to mention its base in al-Qayrawan – had already lost its strength and reached a natural limit."

The idea that the battle isn't that important is perhaps best summed up by Franco Cardini in Europe and Islam:

Even though we need to be careful not to minimize or 'demythologize' the importance of the event, no one now thinks it was crucial. The 'myth' of that particular military fight lives on today as a common media saying, and nothing is harder to get rid of. It is well known how the propaganda spread by the Franks and the papacy praised the victory that happened on the road between Tours and Poitiers...

In their introduction to The Reader's Companion to Military History, Robert Cowley and Geoffrey Parker summarize this side of the modern view of the Battle of Tours by saying:

The study of military history has changed a lot recently. The old way of just focusing on battles and trumpets won't do anymore. Things like economics, supplies, intelligence, and technology now get the attention once given only to battles and campaigns and how many people died. Words like "strategy" and "operations" have new meanings that might not have been understood a generation ago. Changing attitudes and new research have changed our views of what once seemed most important. For example, several of the battles that Edward Shepherd Creasy listed in his famous 1851 book The Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World are barely mentioned here. And the fight between Muslims and Christians at Poitiers-Tours in 732, once thought of as a turning point, has been downgraded to just a raid.

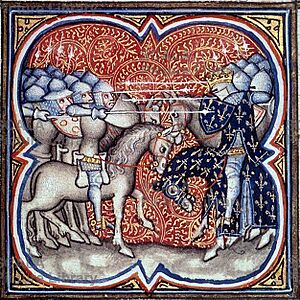

Images for kids

See also

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |