Leopold von Ranke facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Leopold von Ranke

|

|

|---|---|

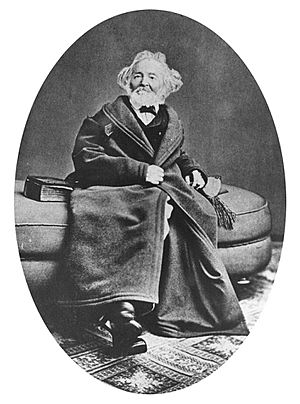

1875 portrait of Ranke by Adolf Jebens

|

|

| Born |

Leopold Ranke

21 December 1795 Wiehe, Saxony, Holy Roman Empire

|

| Died | 23 May 1886 (aged 90) |

| Nationality | German |

| Alma mater | University of Leipzig |

| Occupation | Historian |

| Known for | Rankean historical positivism Historism |

| Scientific career | |

| Institutions | University of Berlin |

| Notable students | Heinrich von Sybel Wilhelm Dilthey Friedrich Wilhelm Schirrmacher Philipp Jaffé |

Leopold von Ranke (born 21 December 1795 – died 23 May 1886) was a famous German historian. He is known as one of the people who started modern history writing. He believed in using original documents, called primary sources, to understand the past.

Ranke also helped create the "seminar" teaching method. In this method, students work closely with a professor to study and discuss historical documents. He focused on looking at old records and papers in archives. This way of studying history became very important.

He was made a nobleman in 1865, which is why "von" was added to his name. Ranke greatly influenced how history was written in the Western world. He is seen as a symbol of the high quality of German historical studies in the 1800s.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Ranke was born in Wiehe, a town in Saxony, which is now part of Germany. His family had many Lutheran pastors and lawyers. He learned a lot at home and also went to a high school called Schulpforta.

From a young age, he loved Ancient Greek and Latin languages, and his family's Lutheranism faith. In 1814, Ranke went to the University of Leipzig. There, he studied old languages (Classics) and Lutheran theology (the study of religion).

At Leipzig, Ranke became very good at philology, which is the study of language in historical sources. He was skilled at translating old texts into German. He enjoyed reading ancient writers like Thucydides and Livy. He also liked modern thinkers such as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Immanuel Kant.

Ranke was not very interested in the history books written at his time. He felt they were just collections of facts without deep understanding.

Starting a Career in History

Between 1817 and 1825, Ranke worked as a teacher. He taught classic languages at a high school in Frankfurt an der Oder. During this time, he became very interested in history. He wanted to help make history a more professional field. He also believed he could see God's plan in historical events.

In 1824, Ranke published his first important book. It was called Histories of the Latin and Teutonic Peoples from 1494 to 1514. For this book, he used many different types of sources. These included diaries, letters, government papers, and eyewitness accounts. This was unusual for historians at that time.

Because of his impressive work, Ranke was offered a job at the University of Berlin. He became a professor there in 1825 and taught for almost 50 years. He used his seminar system to teach students how to check if historical sources were reliable.

Ranke was the first historian to use the many old diplomatic records from Venice. These records covered the 1500s and 1600s. He also sent his students to different archives to find information. In his classes, he taught that history should be told "the way it happened." This idea made him a pioneer in critical historical science.

Key Historical Works

In 1829, Ranke wrote a short book called The Serbian Revolution. He got the information for this book from Vuk Karadžić, a Serb who had seen the events himself. This book was later made longer and renamed Serbia and Turkey in the 19th Century.

From 1832 to 1836, Ranke started and edited a journal called Historische-Politische Zeitschrift. He used this journal to share his conservative ideas. He believed that each state had a special character given by God. He encouraged people to be loyal to their own state, like Prussia. He also disagreed with the ideas of the French Revolution, saying they were only for France.

Between 1834 and 1836, Ranke published The Popes of Rome, Their Church and State in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. Even though he was Protestant, he used private papers from Rome and Venice to write about the history of the papacy. In this book, he created the term "Counter-reformation".

Ranke strongly believed in using primary sources. He wrote that modern history should be based on what eyewitnesses said and on original documents. Many people praised his book for being fair and balanced. Even a Catholic historian, Lord Acton, said it was the most objective study of the 16th-century papacy.

In 1841, Ranke became the official historian for the Prussian court. He also became a member of important academies in the Netherlands and the United States. In 1843, he married Clarissa Helena Graves from Dublin, Ireland.

From 1847 to 1848, Ranke published Memoirs of the House of Brandenburg and History of Prussia. This book looked at the history of the Hohenzollern family and the state of Prussia. Some Prussian nationalists were upset because Ranke showed Prussia as a typical German state, not just a great power.

Between 1852 and 1861, Ranke published French History Mainly in the 16th and 17th Centuries. This five-volume work covered the period from Francis I to Louis XIV. He received more praise for being fair, even though he was German.

In 1854, Ranke gave lectures where he said that "every age is next to God." This meant that every period in history is special and should be understood on its own terms. He believed that God sees all historical periods as equally important. Ranke did not think that history was just about "progress" from one period to the next. For him, the Middle Ages were not worse than the Renaissance; they were just different.

From 1854 to 1857, Ranke published History of the Reformation in Germany. He used many letters from ambassadors to explain the Protestant Reformation as a mix of politics and religion. He also wrote a long, nine-volume History of England between 1859 and 1884.

Later Life and Legacy

Ranke received many honors in his later years. He was made a nobleman in 1865. He also became an honorary citizen of Berlin in 1885. In 1884, he was the first honorary member of the American Historical Association.

After he retired in 1871, Ranke kept writing. He wrote about German history, including the French Revolutionary Wars. In 1880, he started a huge six-volume work on world history. He began with ancient Egypt and the Israelites. When he died in Berlin in 1886 at age 90, he had only reached the 12th century. However, his assistants used his notes to finish the series up to 1453.

After his wife died in 1871, Ranke became partly blind. He needed assistants to read to him. After Ranke's death, Syracuse University bought his large collection of 25,000 books and other materials.

How Ranke Studied History

Ranke believed that general theories could not explain all of history. Instead, he focused on specific times and used quotes from original sources. He said that history should "show what actually happened" (wie es eigentlich gewesen ist). This famous phrase became a guiding idea for many historians.

There has been much discussion about what "how things actually were" truly means. Some think it means historians should only list facts without explaining them. Others believe Ranke meant that historians should find the deeper meaning behind the facts. Ranke also believed historians should look for God's influence in history.

In the 1800s, Ranke's way of studying history was very popular. His ideas became the main way history was written in the Western world. However, some people criticized his work. For example, Karl Marx felt that Ranke sometimes did what he criticized other historians for doing.

Later, in the mid-1900s, historians like E. H. Carr and Fernand Braudel challenged Ranke's ideas. They argued that historians do not just report facts; they also choose which facts to use and how to interpret them.

Honours and Awards

Baden: Knight of the Order of the Zähringer Lion, 1st Class, 1856

Baden: Knight of the Order of the Zähringer Lion, 1st Class, 1856 Kingdom of Bavaria:

Kingdom of Bavaria:

- Bavarian Maximilian Order for Science and Art, 1853

Belgium: Knight of the Order of Leopold (civil), 22 October 1841

Belgium: Knight of the Order of Leopold (civil), 22 October 1841 Grand Duchy of Hesse: Commander of the Merit Order of Philip the Magnanimous, 1st Class, 31 March 1875

Grand Duchy of Hesse: Commander of the Merit Order of Philip the Magnanimous, 1st Class, 31 March 1875 Kingdom of Greece: Grand Commander of the Order of the Redeemer

Kingdom of Greece: Grand Commander of the Order of the Redeemer Kingdom of Serbia: Grand Cross of the Order of Saint Sava

Kingdom of Serbia: Grand Cross of the Order of Saint Sava

Sweden-Norway: Commander Grand Cross of the Order of the Polar Star

Sweden-Norway: Commander Grand Cross of the Order of the Polar Star Württemberg:

Württemberg:

- Knight of the Order of the Württemberg Crown, 1st Class, 1842

Kingdom of Prussia:

Kingdom of Prussia:

- Knight of the Order of the Red Eagle, 2nd Class with Oak Leaves, 1850

- Commander's Eagle of the Royal House Order of Hohenzollern, 14 October 1851

- Pour le Mérite (civil), 22 January 1855

- Knight of the Royal Order of the Crown, 1st Class (60 years), 17 February 1877

Selected Works

- Histories of the Romanic and Germanic Peoples from 1494 to 1514 (1824)

- Serbian Revolution (1829)

- The Roman Popes in the Last Four Centuries (1834–1836)

- Memoirs of the House of Brandenburg and History of Prussia (1847–1848)

- Civil Wars and Monarchy in France, in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries (1852–1861)

- The German Powers and the Princes' League (1871–1872)

- Origin and Beginning of the Revolutionary Wars 1791 and 1792 (1875)

- Hardenberg and the History of the Prussian State from 1793 to 1813 (1877)

- World history: The Roman Republic and Its World Rule (2 volumes, 1886)

Works in English Translation

- The Ottoman and the Spanish Empires, in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries, Whittaker & Co., 1843.

- Memoirs of the House of Brandenburg and History of Prussia During the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries, Vol. 2, Vol. 3, John Murray, 1849.

- Civil Wars and Monarchy in France, in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries, Richard Bentley, 1852.

- The History of Servia and the Servian Revolution, Henry G. Bohn, 1853.

- History of England Principally in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries, Volume Five, Volume Six, Oxford: At the Clarendon Press, 1875.

- Universal History: The Oldest Historical Group of Nations and the Greeks, Charles Scribner's Sons, 1884.

- History of the Popes: Their Church and State, Vol. 2, Vol. 3, P. F. Collier & Son, 1901. (Translated by Sarah Austin); first translation by Eliza Foster in 1847-48.

- History of the Reformation in Germany, George Routledge & Sons, 1905.

- History of the Latin and Teutonic Nations, 1494–1514, George Bell & Sons, 1909.

- The Secret of World History: Selected Writings on the Art and Science of History, Roger Wines, ed., Fordham University Press, 1981.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Leopold von Ranke para niños

In Spanish: Leopold von Ranke para niños