Vuk Karadžić facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Vuk Karadžić

|

|

|---|---|

| Вук Караџић | |

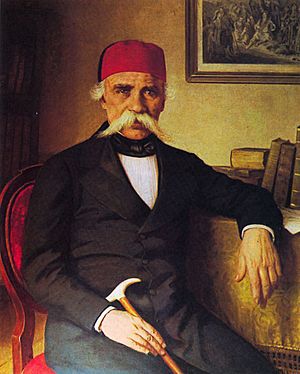

Vuk Karadžić, around 1850

|

|

| Born |

Vuk Stefanović Karadžić

6 November 1787 |

| Died | 7 February 1864 (aged 76) |

| Resting place | St. Michael's Cathedral, Belgrade, Serbia |

| Alma mater | Belgrade Higher School |

| Occupation | Philologist, linguist |

| Known for | Serbian language reform Serbian Cyrillic alphabet |

| Movement | Serbian Revival |

| Spouse(s) | Anna Maria Kraus |

| Children | inter alia, Mina Karadžić |

Vuk Stefanović Karadžić (Serbian Cyrillic: Вук Стефановић Караџић, pronounced [ʋûːk stefǎːnoʋitɕ kâradʒitɕ]; 6 November 1787 – 7 February 1864) was a very important Serbian expert in languages, folk stories, and how languages work. He is known as one of the main people who changed and improved the modern Serbian language.

He collected and saved many Serbian folk tales. Because of this, Encyclopædia Britannica called him "the father of Serbian folk-literature scholarship." He also wrote the first Serbian dictionary using the new, improved language. Plus, he translated the New Testament (a part of the Christian Bible) into the new Serbian writing style and language.

Vuk Karadžić was famous in other countries too. He was known by important thinkers like Jacob Grimm (one of the Grimm brothers), Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and historian Leopold von Ranke. Karadžić was the main source of information for Ranke's book Die serbische Revolution ("The Serbian Revolution"), which was written in 1829.

Contents

Biography: The Story of Vuk Karadžić's Life

Early Life and Family Background

Vuk Karadžić was born into a Serbian family. His parents were Stefan and Jegda. They lived in the village of Tršić, near Loznica. This area was part of the Ottoman Empire at the time. Today, it is in Serbia.

His family came from a place called Drobnjaci. His mother was from Ozrinići, which is now in Montenegro. Many babies in his family did not survive. So, he was named Vuk, meaning "wolf." People believed this name would protect him from evil spirits.

Vuk's Education and Early Career

Vuk was lucky because he had a relative, Jevta Savić Čotrić. Jevta was the only person in the area who could read and write. He taught Vuk how to do both. Vuk then went to the Tronoša Monastery in Loznica to continue learning.

At the monastery, he learned to write using a reed as a pen. He made ink from gunpowder. He often wrote on cartridge wrappings because proper paper was hard to find. Regular schools were not common back then. His father even brought him home from the monastery. This was because Vuk spent more time looking after animals than studying.

In 1804, the First Serbian uprising began. Serbs wanted to be free from the Ottomans. Vuk tried to join a high school in Sremski Karlovci, but he was too old at 19. He then went to Petrinja to learn Latin and German.

Later, he met a respected scholar, Dositej Obradović, in Belgrade. Belgrade was now controlled by the Serbs fighting for freedom. Vuk asked Obradović for help with his studies, but Obradović turned him away. Disappointed, Vuk worked as a scribe and a customs officer. This was during the War of Independence (1804-1813). When Belgrade's Grande école (which became the University of Belgrade) was founded, Vuk became one of its students.

Later Life, Work, and Passing

Vuk became ill and traveled for medical help. He went to Pest and Novi Sad. He could not get treatment for his leg. It is said that he chose to use a wooden prosthetic leg instead of having his own leg removed.

By 1810, Vuk returned to Serbia. He could not serve in the military because of his leg. He worked as a secretary for military leaders. His experiences later inspired two of his books. In 1813, the Ottomans defeated the Serbian rebels. Vuk then moved to Vienna. There, he met Jernej Kopitar, a linguist interested in Slavic languages. Kopitar helped Vuk a lot with his work to change the Serbian language and its writing rules. Another important person who helped Vuk with his language work was Sava Mrkalj.

In 1814 and 1815, Vuk published two books of Serbian Folk Songs. More books were added later, making it nine volumes in total. These amazing songs became famous across Europe and America. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe said some of them were "excellent."

In 1824, Vuk sent his folk song collection to Jacob Grimm. Grimm was very impressed, especially by a song called The Building of Skadar. Vuk had written it down after hearing Old Rashko sing it. Grimm translated it into German. He compared these songs to the great poems of Homer. He called The Building of Skadar "one of the most touching poems of all nations and all times." Many famous writers from France, Russia, Finland, and England also translated and admired Vuk's collected songs.

Vuk continued collecting songs into the 1830s. In 1834, he visited Montenegro. There, he met Vuk Vrčević, a young writer. Vrčević became Vuk Karadžić's loyal helper. He collected folk songs and tales and sent them to Vuk in Vienna for many years. Another helpful person was Priest Vuk Popović. Both Vrčević and Popović worked hard to gather information about Serbian culture, folk stories, and words for Karadžić. Other helpers joined later, like Milan Đ. Milićević.

Most of Vuk Karadžić's works were not allowed to be published in Serbia and Austria. This was during the rule of Prince Miloš Obrenović. Prince Miloš worried that Vuk's works, even poems, could make people feel too patriotic. He feared this might lead them to fight against the Ottoman Empire. This would have caused problems for Prince Miloš, who had made a difficult peace with the Ottomans.

However, Vuk's works were highly praised in other places, especially in the Russian Empire. The Emperor of All Russia even gave Vuk a full pension in 1826.

Vuk Karadžić passed away in Vienna. His daughter, Mina Karadžić, who was a painter and writer, and his son Dimitrije, a military officer, survived him. In 1897, his body was moved to Belgrade. He was buried with great honors next to Dositej Obradović at St. Michael's Cathedral (Belgrade).

Vuk Karadžić's Important Work

Reforming the Serbian Language

In the late 1700s and early 1800s, many European countries changed their languages. Vuk Karadžić did the same for the Serbian language. He made the Serbian Cyrillic alphabet simpler. He followed a rule: "Write as you speak, and read as it is written." This means each letter should represent one sound.

Vuk's changes made the Serbian language more modern. It moved away from old church language and became closer to how people actually spoke. For example, he removed old letters that were not used in common Serbian speech. He also added 6 new Cyrillic letters to make writing easier. In 1847, he published his translation of the New Testament into this new Serbian language.

Before Vuk, the written Serbian language had many words from the Orthodox church. It also had many words borrowed from Russian Church Slavonic. Vuk suggested getting rid of this old written language. He wanted to create a new one based on the Eastern Herzegovina dialect, which was his own dialect. Some Serbian church leaders and other language experts disagreed with him. They thought the Eastern Herzegovinian dialect was too different.

But Vuk strongly believed his language standard was closer to how most people spoke. He felt it would be easier for more people to understand and write. He called his dialect Herzegovinian because he believed Serbian was spoken "in the purest and most correct way in Herzegovina and in Bosnia." Even though he never visited those lands, his family came from Herzegovina.

In the end, Vuk Karadžić's ideas won. In 1850, Vuk Karadžić and Đuro Daničić signed the Vienna Literary Agreement. This agreement helped create the foundation for what became known as the Serbo-Croatian language. However, Karadžić himself always called the language "Serbian."

Vuk Karadžić's work to standardize the language continued for the rest of the century. His ideas greatly influenced language experts across Southeast Europe. Serbian newspapers in Austria-Hungary and Serbia began to use his new language standard. In Croatia, a linguist named Tomislav Maretić used Karadžić's work to create rules for Croatian grammar.

Vuk Karadžić believed that all South Slavs who spoke the Shtokavian dialect were Serbs. He thought they all spoke the Serbian language. However, this idea is still debated by experts today. Later, Karadžić changed his view. He realized that Croats did not agree with him. So, he started to define the Serbian nation based on the Orthodox religion and the Croatian nation based on Catholicism.

Vuk's Contributions to Literature

Besides his language changes, Vuk Karadžić also helped folk literature. He used the culture of ordinary people as his base. Because he grew up in a village, he knew a lot about oral stories. He gathered these stories for his collection of folk songs, tales, and proverbs.

Vuk did not see peasant life as just romantic. He saw it as a very important part of Serbian culture. He collected many books of folk stories and poems. This included a book with over 100 lyrical and epic songs. He remembered these songs from his childhood and wrote them down. He also published the first dictionary of everyday Serbian language.

Vuk often did not get much money for his work. Sometimes, he lived in poverty. But in his last nine years, he did receive a pension from Prince Miloš Obrenović. Sometimes, Vuk also used songs that other collectors had written down, not just those he heard himself.

His work was very important in showing the value of the Kosovo Myth. This myth is a big part of Serbian national identity and history. Karadžić collected traditional epic poems about the Battle of Kosovo. He released them as the "Kosovo cycle." This became the final version of the myth. He mostly published oral songs, especially about the heroic deeds of Prince Marko and events related to the Kosovo Battle. He wrote them down exactly as the singers sang them. Vuk collected most of the poems about Prince Lazar near monasteries. This was because the main church center of the Serbian Orthodox Church had moved there.

Other Important Work by Vuk Karadžić

Besides his language and literature work, Vuk Karadžić also helped with Serbian anthropology. This is the study of human societies and cultures. He wrote notes about how the human body looks. He also wrote about everyday life and customs.

He introduced many words for body parts into the Serbian language. These words are still used today in science and daily talk. He also wrote about how the environment affects people. He included details on food, living conditions, cleanliness, illnesses, and funeral customs. This part of Vuk Karadžić's work is not as well known, but it is still very valuable.

Recognition and Lasting Legacy

A historian named Jovan Deretić said about Vuk's work: "During his fifty years of tireless activity, he accomplished as much as an entire academy of sciences." This shows how much he achieved.

Vuk Karadžić was honored all over Europe. He became a member of many important groups. These included the Imperial Academy of Sciences in Vienna and the Prussian Academy of Sciences. He also received several honorary doctorates. Kings and emperors gave him awards. In 1987, UNESCO declared it the "Year of Vuk Karadžić." He was also made an honorary citizen of Zagreb.

In 1964, 100 years after Vuk's death, students built an outdoor theater in Tršić. This was for events like the Vukov sabor, a festival celebrating Vuk's work. In 1987, Tršić was completely renovated as a cultural site. A road was also built from Vuk's home to the Tronoša monastery. Vuk Karadžić's birth house was declared a special cultural monument in 1979. It is protected by the Republic of Serbia. Today, many families in Tršić offer rural tourism, turning their homes into guest houses. A TV series about his life was shown on Serbian television. His picture is often seen in Serbian schools. The former countries of Yugoslavia and Serbia and Montenegro also gave out a state award called the Order of Vuk Karadžić.

The Vuk's Foundation continues to keep Vuk Stefanović Karadžić's legacy alive. In Serbia, students who get the best grades in all subjects throughout primary or secondary school receive a "Vuk Karadžić diploma." These students are known as "Vukovac," meaning they are part of an elite group of top-performing students.

Selected Works by Vuk Karadžić

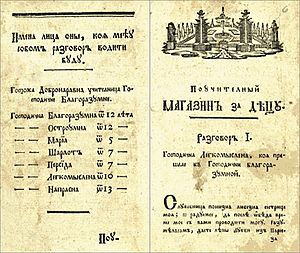

- Mala prostonarodna slaveno-serbska pesnarica, Vienna, 1814

- Pismenica serbskoga jezika, Vienna, 1814

- Narodna srbska pjesnarica II, Vienna, 1815

- Srpski rječnik istolkovan njemačkim i latinskim riječma (Serbian Dictionary, with German and Latin words), Vienna, 1818

- Narodne srpske pripovjetke, Vienna, 1821, updated edition, 1853

- Narodne srpske pjesme I-V, Vienna and Leipzig, 1823–1864

- Luke Milovanova Opit nastavlenja k Srbskoj sličnorečnosti i slogomjerju ili prosodii, Vienna, 1823

- Mala srpska gramatika, Leipzig, 1824

- Žizni i podvigi Knjaza Miloša Obrenovića, Saint Petersburg, 1825

- Danica I-V, Vienna, 1826–1834

- Žitije Đorđa Arsenijevića, Emanuela, Buda, 1827

- Miloš Obrenović, knjaz Srbije ili gradja za srpsku istoriju našega vremena, Buda, 1828

- Narodne srpske poslovice i druge različne, kao i one u običaj uzete riječi, Cetinje, 1836

- Montenegro und die Montenegriner: ein Beitrag zur Kenntnis der europäischen Türkei und des serbischen Volkes, Stuttgart and Tübingen, 1837

- Pisma Platonu Atanackoviću, Vienna, 1845

- Kovčežić za istoriju, jezik i običaje Srba sva tri zakona, Vienna, 1849

- Primeri Srpsko-slovenskog jezika, Vienna, 1857

- Praviteljstvujušči sovjet serbski za vremena Kara-Đorđijeva, Vienna, 1860

- Srpske narodne pjesme iz Hercegovine, Vienna, 1866

- Život i običaji naroda srpskog, Vienna, 1867

- Nemačko srpski rečnik, Vienna, 1872

- Sunce se djevojkom ženi

Translations:

- New Testament, Vienna, 1847

A Common Misquote About Language

There is a famous saying often thought to be from Vuk Stefanović Karadžić in Serbia: "Write as you speak, and read as it is written." However, this idea actually came from a German language expert named Johann Christoph Adelung. Vuk Karadžić simply used this rule to help with his language changes.

Because of this common mistake, the entrance exam for the University of Belgrade Faculty of Philology sometimes asks about who really said this quote. It's a bit of a trick question!

See also

In Spanish: Vuk Stefanović Karadžić para niños

In Spanish: Vuk Stefanović Karadžić para niños

- Vienna Literary Agreement

- Museum of Vuk and Dositej

People Connected to Vuk Karadžić's Work

- Živana Antonijević

- Tešan Podrugović

- Lukijan Mušicki

- Filip Višnjić

- Sima Milutinović Sarajlija

- Dimitrije Davidović

- Branko Radičević

- Petar II Petrović Njegoš

- Ljudevit Gaj

- Franz Miklosich

- Ivan Mažuranić

- Sava Mrkalj