Phalanx facts for kids

A phalanx was a special military formation used in ancient times. It was a big, rectangular block of soldiers, mostly heavy infantry. These soldiers carried long spears, pikes, or similar pole weapons. The word "phalanx" is often used to describe how soldiers fought in Ancient Greece. However, ancient writers also used it for any large group of infantry soldiers.

Today, the term "phalanx" doesn't mean a specific army unit. Instead, it describes how troops were arranged in battle. It tells us about the formation of an army's foot soldiers, not their exact number or what they were made of. Many armies throughout history used formations similar to the phalanx. This article will mainly focus on the phalanx as it was used in Ancient Greece, the Hellenistic world, and other ancient states influenced by Greek culture.

Contents

History of the Phalanx

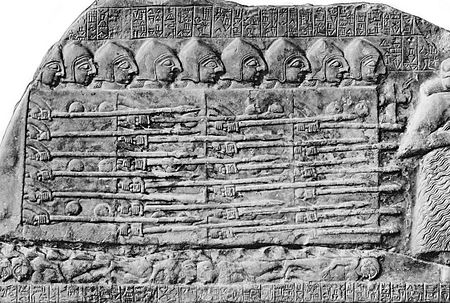

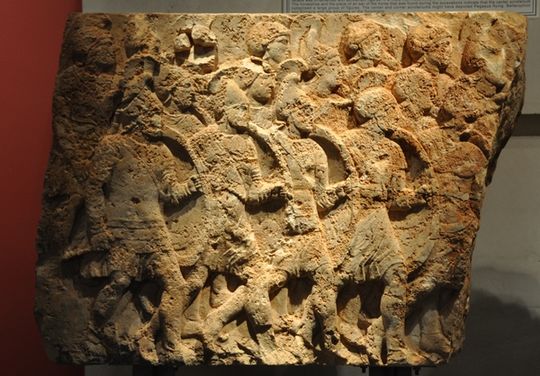

The earliest known picture of a phalanx-like formation comes from the Sumerian Stele of the Vultures. This carving is from the 25th century BC. It shows soldiers with spears, helmets, and large shields that covered their whole bodies. Ancient Egyptian soldiers also used similar formations.

The word "phalanx" itself comes from Homer's ancient Greek word "φαλαγξ." Homer used it to describe hoplites fighting in an organized battle line. He used the term to show that this was different from the individual duels often found in his poems.

Historians aren't sure if the Greek phalanx was directly inspired by these earlier formations. The idea of a "shield wall" (where shields connect) and a "spear hedge" (many spears pointing out) was known by many armies. So, these similarities might have developed independently in different places.

Many historians believe the hoplite phalanx in ancient Greece started in the 8th century BC in Sparta. However, this idea is being re-examined. It's now thought that the formation might have been created in the 7th century BC. This was after the aspis (a large shield) was introduced by the city of Argos. This shield made the phalanx formation possible. An ancient vase from 650 BC, called the Chigi vase, shows hoplites with aspis shields, spears, and other gear. This supports the idea of a later origin.

Another idea is that the basic parts of the phalanx existed earlier. But they couldn't be fully developed without better technology. Things like working together as a team and using large groups of soldiers were already known. This suggests the Greek phalanx was the final, improved version of an idea that grew over many years. As weapons and armor got better in different city-states, the phalanx became more complex and effective.

How the Phalanx Worked

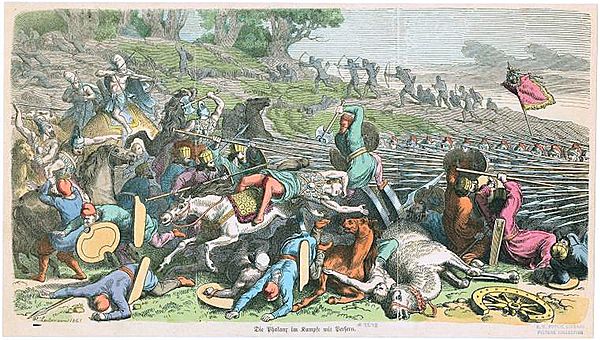

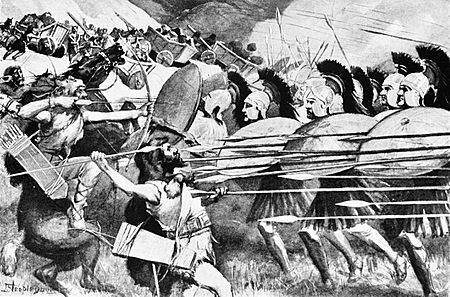

The hoplite phalanx was a formation where soldiers called hoplites lined up very close together. This was common in Greece between 800 and 350 BC. The hoplites would link their shields, creating a solid wall. The soldiers in the first few rows would point their spears forward over the shields. This meant the phalanx showed a strong shield wall and many spear points to the enemy. It made it very hard for enemies to attack them from the front. It also allowed more soldiers to fight at the same time, not just those in the very front.

Battles between two phalanxes usually happened on open, flat ground. This made it easier for the soldiers to move forward and keep their formation. Rough or hilly areas would make it hard to keep a straight line. This would make the phalanx less effective. So, Greek city-states often chose specific flat areas for their battles. Usually, the battle ended when one side ran away to safety.

The phalanx usually moved forward at a walking pace. Sometimes, they might speed up in the last few yards. Moving slowly helped them keep their formation. If the formation broke, it would be useless and could even be dangerous for the attacking army. If hoplites did speed up at the end, it was to gain momentum for the first clash. The historian Herodotus said the Greeks at the Battle of Marathon were the first to charge at a run. Many historians think they did this to reduce losses from Persian arrows. When two phalanxes crashed, many spears in the front row could break. Soldiers in the front might also get hurt or killed in the collision.

The spears used by a phalanx had a spike at the back called a sauroter. In battle, soldiers in the back rows used this spike to finish off fallen enemy soldiers.

The "Pushing" Idea (Othismos)

One idea about phalanx battles is that they became a "physical pushing match." In this theory, the battle depended on the bravery of the front-line soldiers. Those behind them would keep pushing forward with their shields. The whole formation would constantly press ahead to try and break the enemy's line. This is a popular idea among historians. When two phalanxes met, it became a struggle of pushing. Historians like Victor Davis Hanson say that very deep phalanx formations only make sense if they were needed for this pushing. Soldiers behind the first two rows couldn't use their spears to stab.

However, no ancient Greek art shows a phalanx pushing match. So, this idea comes from educated guesses, not direct accounts. It's still a debated topic among experts. The Greek word for "push" was used in a similar way to how we use it in English. It could mean a literal push, but it could also mean a strong argument.

For example, if Othismos was truly a physical push, then a deeper phalanx should always win. The strength of individual soldiers wouldn't matter as much as having more rows pushing. But there are many examples of shallower phalanxes holding their ground against deeper ones. At the Battle of Delium in 424 BC, the Athenian left flank was eight men deep. It held off a Theban formation that was 25 men deep for a long time. It's hard to imagine eight men physically pushing back 25 opponents for half a battle.

These arguments have led to many criticisms of the "physical pushing" theory. Historians like Adrian Goldsworthy argue that the pushing model doesn't fit with the average number of casualties in hoplite battles. It also doesn't match the practical challenges of moving large groups of men in a fight. This debate is still ongoing among scholars.

There are also practical problems with the pushing theory. In a shoving match, an eight-foot spear is too long to fight effectively or block attacks. Spears help soldiers keep enemies at a distance and strike multiple foes. A pushing match would bring enemies so close that a quick knife stab could kill the front row instantly. The crowd of men would also prevent the formation from moving back or retreating. This would lead to much higher casualties than what was recorded. Such a battle would also end very quickly, not last for hours.

Shields in the Phalanx

Each hoplite carried his shield on his left arm. This protected him and the soldier to his left. This meant that the soldiers on the far right side of the phalanx were only half-protected. In battle, enemy phalanxes would try to attack this weak right side. This also meant that a phalanx would naturally drift to the right during battle. This happened because hoplites tried to stay behind their neighbor's shield. Some groups, like the Spartans at the Battle of Nemea, tried to use this drift to their advantage. They would sacrifice their left side (often made up of allied troops) to try and get around the enemy's flank. It's unlikely this strategy worked often, as it's not mentioned much in ancient Greek writings.

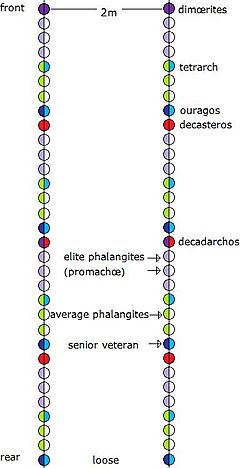

Each row in a phalanx had a leader. There was also a rear officer, called the ouragos, who kept order at the back. Hoplites had to trust their neighbors to protect them and be willing to protect their neighbors in return. A phalanx was only as strong as its weakest parts. The phalanx's success depended on how well hoplites could keep their formation in battle. It also depended on how well they could hold their ground, especially against another phalanx. For this reason, friends and family were often grouped together. This gave them a reason to support each other and made them less likely to panic or run away. The more disciplined and brave the army, the more likely it was to win. Battles between Greek city-states often ended with one side simply fleeing before much fighting happened. The Greek word dynamis (the "will to fight") describes the strong desire that kept hoplites in formation.

Now of those, who dare, abiding one beside another, to advance to the close fray, and the foremost champions, fewer die, and they save the people in the rear; but in men that fear, all excellence is lost. No one could ever in words go through those several ills, which befall a man, if he has been actuated by cowardice. For 'tis grievous to wound in the rear the back of a flying man in hostile war. Shameful too is a corpse lying low in the dust, wounded behind in the back by the point of a spear.

—Tyrtaeus, The War Songs of Tyrtaeus

Hoplite Weapons and Armor

Each hoplite bought his own equipment. The main weapon was a spear called a dory, which was about 7 to 9 feet long (2.1–2.7 meters). Soldiers held it with one hand, while the other hand held their shield (the aspis). The spearhead was usually shaped like a curved leaf. The back of the spear had a spike called a sauroter ('lizard-killer'). This spike was used to stick the spear in the ground. It also served as a backup weapon if the main spear shaft broke. This was a common problem, especially for soldiers in the first clash. If the spear broke, hoplites could easily switch to the sauroter. Soldiers in the back rows used this spike to finish off fallen enemies as the phalanx moved forward.

Over time, the standard hoplite armor changed a lot. Early hoplites usually wore a bronze breastplate, a bronze helmet with cheekplates, and leg guards (greaves). Later, in the classical period, breastplates became less common. They were replaced by a corselet, which some believe was made of linothorax (layers of glued linen) or leather. Sometimes, this was covered with overlapping metal scales. Eventually, even greaves were used less often. However, some heavier armor remained, as noted by the historian Xenophon as late as 401 BC.

These changes showed a balance between being able to move easily and having good protection. This was especially important as cavalry became more common in the Peloponnesian War. There was also a growing need to fight light troops, who were increasingly used to counter the hoplite's main role in battle. Still, bronze armor was used in some form until the end of the hoplite era. Some archaeologists suggest that bronze armor didn't always offer the best protection from direct hits compared to padded corselets. They think its continued use might have been a sign of status for those who could afford it.

Hoplites also carried a short sword called a xiphos. This was used as a secondary weapon if the dory broke or was lost. Swords found at ancient sites were typically about 24 inches (60 cm) long. These swords had two sharp edges, so they could be used for both cutting and thrusting. They were often used to stab or cut at an enemy's neck in close combat.

Hoplites carried a round shield called an aspis. It was made of wood and covered in bronze. It was about 3.3 feet (1 meter) wide and very heavy, weighing 8–15 kg (18–33 lbs). This medium-sized shield was large for the time. Its dish-like shape allowed it to rest on the soldier's shoulder. This was important, especially for soldiers in the back rows. While these soldiers helped push forward, they didn't have to hold up the heavy shield. But the round shield had some downsides. Despite being easy to move and having a protective curve, its round shape created small gaps in the shield wall at the top and bottom. (The top gaps were somewhat covered by spears sticking out.) To reduce bottom gaps, thick leather curtains were sometimes used. However, not all hoplites used them, possibly only those in the first row. These curtains added weight and cost. These gaps left parts of the hoplite exposed to dangerous spear thrusts and were a constant weakness for soldiers in the front lines.

Macedonian Phalanx Weapons

The phalanx used by the Ancient Macedonian kingdom and later Hellenistic states was an improved version of the hoplite phalanx. These "phalangites" used a much longer spear called a sarissa and wore less heavy armor. The sarissa was the pike used by the ancient Macedonian army. Its exact length is unknown, but it was likely twice as long as the dory, possibly 14 to 18 feet (4.3 to 5.5 meters) long. The great length of the pike was balanced by a counterweight at the back. This also worked as a spike, allowing the sarissa to be planted in the ground.

Because of its great length, weight, and different balance, a sarissa had to be held with two hands. This meant the large aspis shield was no longer practical. Instead, phalangites strapped a smaller pelte shield (usually used by light skirmishers) to their left forearm. Some newer ideas, based on ancient frescoes, suggest the shields were larger than a pelte but smaller than an aspis. They might have hung from the left shoulder or both shoulders with straps. The shield would still have inner straps to be held like a smaller aspis if the fight became close-quarters with swords.

Even with a smaller shield wall, the extreme length of the sarissa kept enemies further away. The pikes of the first three to five rows could all reach the enemy in front of the first row. This pike had to be held underhand. If held overhead, the shield would block the soldier's view. It would also be very hard to pull a sarissa out of anything it got stuck in (like the ground, shields, or enemies) if it was thrust downwards due to its length. The Macedonian phalanx was not as good at forming a shield wall, but its longer spears made up for this. This type of phalanx also made it less likely that battles would turn into a pushing match.

Phalanx Formations and Combat

Phalanx Size and Depth

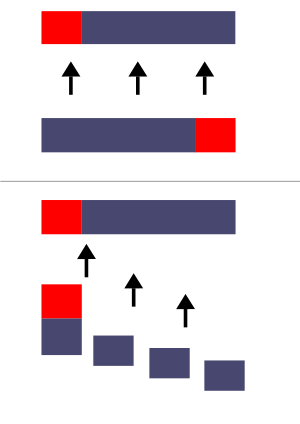

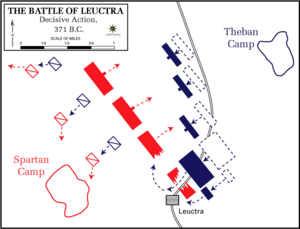

Hoplite phalanxes usually lined up in rows that were eight men deep or more. Macedonian phalanxes were typically 16 men deep, and sometimes even 32 men deep. There were some extreme cases. At the battles of Leuctra and Mantinea, the Theban general Epaminondas made the left side of his phalanx an incredible fifty men deep. At the Battle of Marathon, when depth was less important, phalanxes were only four men deep.

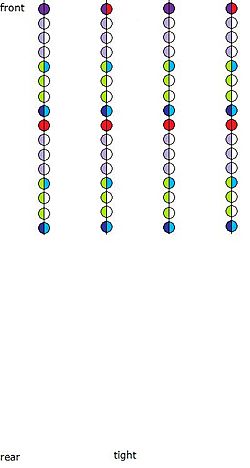

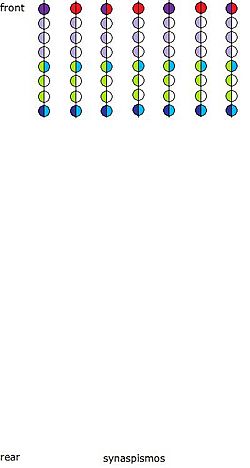

The depth of the phalanx could change based on the situation and the general's plans. When marching, a loose formation (eis bathos) was used. This allowed soldiers to move more freely and keep order. This was also the starting battle formation, as it let friendly units pass through, whether attacking or retreating. In this loose formation, the phalanx was twice as deep as normal. Each hoplite took up about 1.8 to 2 meters of space.

When enemy infantry got close, soldiers quickly switched to a dense or tight formation (pycne). In this formation, each man's space was cut in half, and the phalanx depth returned to normal. An even tighter formation, called synaspismos (locked shields formation), was used when the phalanx expected heavy pressure, many arrows, or frontal cavalry charges. In synaspismos, the depth was half that of a normal phalanx, and each man occupied as little as 0.45 meters of space.

Stages of Phalanx Combat

Hoplite combat usually followed several steps:

- Ephodos: The hoplites stopped singing their battle hymns (pæanes). They then moved towards the enemy, slowly gaining speed and momentum. Just before they hit the enemy, they would shout war cries (alalagmœ). Famous war cries included the Athenian (eleleleleu!) and the Macedonian (alalalalai!).

- Krousis: The two opposing phalanxes met each other almost at the same time along their front lines.

- Doratismos: Soldiers made repeated, quick spear thrusts to break the enemy's formation. The long spears kept enemies apart and allowed men in one row to help their comrades next to them. A poke could also open up an enemy for another soldier to spear him. If a spear got stuck in a shield, a soldier from the back might lend his spear to the disarmed man.

- Othismos: This literally means "pushing." After most spears had broken, the hoplites began to push with their spears and spear shafts against the enemy's shields. This could be the longest part of the battle.

- Pararrhexis: This is when one phalanx broke through the enemy's line. The enemy formation would shatter, and the battle would end. Cavalry would then be used to chase down and defeat the scattered enemy soldiers.

Phalanx Tactics

Early phalanx history mostly involved hoplite armies from different Greek city-states fighting each other. The result was often the same: two rigid formations pushing until one broke. But the phalanx could do more, as shown at the Battle of Marathon (490 BC). Facing a much larger army from Darius I, the Athenians made their phalanx thinner but longer. This prevented the Persians from getting around their sides. Even a thinner phalanx was too strong for the lightly armed Persian infantry. After defeating the Persian wings, the Athenian hoplites on the sides turned inward. They then destroyed the elite Persian troops in the center, leading to a huge victory for Athens. Throughout the Greco-Persian Wars, the hoplite phalanx proved better than the Persian infantry. This was seen in battles like Thermopylae and Plataea.

Perhaps the most famous example of the phalanx's development was the "oblique order." This was made famous at the Battle of Leuctra. There, the Theban general Epaminondas made the right side and center of his phalanx thinner. But he made his left side incredibly deep, fifty men deep. By doing this, Epaminondas changed the usual way phalanxes were set up (where the right side was strongest). This allowed the Thebans to attack the elite Spartan troops on the right side of the enemy phalanx with great force. Meanwhile, the center and right side of the Theban line were pulled back. This kept the weaker parts of the formation from being attacked. Once the Spartan right side was defeated by the Theban left, the rest of the Spartan line also broke. So, by focusing the hoplites' attacking power, Epaminondas was able to defeat an enemy previously thought unbeatable.

Philip II of Macedon spent several years in Thebes as a hostage. He paid close attention to Epaminondas' new ideas. When he returned home, he created a new infantry force that changed the Greek world. Philip's phalangites were the first professional soldiers in Ancient Greece, apart from Sparta. They carried longer spears (the sarissa) and were trained more thoroughly in complex tactics and movements. More importantly, Philip's phalanx was part of a combined army. This army included different types of light skirmishers and cavalry, especially the famous Companion cavalry. The Macedonian phalanx was used to hold the center of the enemy line. Meanwhile, the cavalry and more mobile infantry attacked the enemy's sides. The Macedonian phalanx's superiority over the less flexible armies of the Greek city-states was shown at the Battle of Chaeronea. There, Philip II's army crushed the combined Theban and Athenian phalanxes.

Weaknesses of the Phalanx

The hoplite phalanx was weakest when it faced an enemy with lighter, more flexible troops, especially if it didn't have its own supporting troops. One example is the Battle of Lechaeum. Here, an Athenian group led by Iphicrates defeated an entire Spartan unit (a Mora, 500–900 hoplites). The Athenian force had many light missile troops with javelins and bows. They wore down the Spartans with repeated attacks, causing confusion in the Spartan ranks. The Spartans eventually ran away when they saw Athenian heavy infantry reinforcements trying to flank them by boat.

The Macedonian phalanx had similar weaknesses to the earlier hoplite phalanx. While it was almost unbeatable from the front, its sides and rear were very vulnerable. Once it was fighting, it was hard for it to break away or change direction to face a threat from those sides. So, a phalanx fighting non-phalanx formations needed protection on its sides. This protection came from lighter or more mobile infantry, cavalry, and other units. This was seen at the Battle of Magnesia. Once the Seleucid cavalry on their sides were driven off, the phalanx became stuck. It couldn't attack the Roman soldiers (though they fought bravely and tried to retreat under Roman arrows). But then, elephants on their sides panicked and broke their formation.

The Macedonian phalanx could also lose its tight formation without proper coordination or when moving through rough ground. This could create gaps between different parts of the phalanx. It could also prevent a solid front within those smaller units, causing other parts of the line to bunch up. When this happened, as in the battles of Cynoscephalae and Pydna, the phalanx became open to attacks by more flexible units. Roman legionary centuries, for example, could avoid the long sarissae and fight hand-to-hand with the phalangites.

Another important point is the psychology of the hoplites. The strength of a phalanx depended on soldiers being able to keep their front line strong. It was vital that a phalanx could quickly and smoothly replace fallen soldiers in the front rows. If a phalanx failed to do this in an organized way, the enemy phalanx could break through the line. This often led to a quick defeat. This means that hoplites closer to the front had to be mentally ready to replace a fallen comrade and adapt to their new position without breaking the line.

Finally, most armies that relied heavily on the phalanx often lacked backup forces behind their main battle line. This meant that breaking through the front line or attacking one of its sides often guaranteed victory.

Decline and Later Uses

After reaching its peak with the conquests of Alexander the Great, the phalanx slowly declined. This happened as the Macedonian successor states became weaker. The clever combined tactics used by Alexander and his father were gradually replaced. Armies went back to simpler frontal attacks, like the old hoplite phalanx. The cost of supporting cavalry and other arms, and the widespread use of hired soldiers, made the Diadochi (Alexander's generals who took over his empire) rely on phalanx-versus-phalanx battles during their wars.

The decline of the Diadochi and the phalanx was connected to the rise of Rome and its Roman legions from the 3rd century BC. The Battle of the Caudine Forks showed how clumsy the Roman phalanx could be against the Samnites. The Romans had used the phalanx themselves at first. But they slowly developed more flexible tactics. This led to the three-line Roman legion of the middle Roman Republic, called the Manipular System. Romans used a phalanx for their third line of soldiers, the triarii. These were experienced reserve troops armed with spears called hastae. Rome conquered most of the Macedonian successor states, along with the various Greek city-states and leagues. As these states disappeared, so did the armies that used the traditional phalanx. Later, soldiers from these regions were equipped, trained, and fought using the Roman style.

A phalanx-like formation called the phoulkon appeared in the late Roman and Byzantine armies. It had some features of the classical Greek and Hellenistic phalanxes but was more flexible. It was used more against cavalry than infantry.

However, the phalanx didn't completely vanish. In some battles between the Roman army and Hellenistic phalanxes, like Pydna (168 BC), Cynoscephalae (197 BC), and Magnesia (190 BC), the phalanx performed well. It even pushed back the Roman infantry. But at Cynoscephalae and Magnesia, the phalanx lost because its sides were not protected. At Pydna, the phalanx lost its formation while chasing retreating Roman soldiers. This allowed the Romans to break through. Then, Roman close-combat skills proved decisive. The historian Polybius explained how effective the Roman legion was against the phalanx. He believed the Romans avoided fighting the phalanx where it was strong. Romans only fought when a legion could take advantage of the phalanx's slowness and inability to move easily.

Soldiers armed with spears continued to be important in many armies until reliable firearms became available. These armies didn't always fight in a true phalanx. For example, compare the classical phalanx to the late medieval pike formations.

Some historians have suggested that the Scots under William Wallace and Robert the Bruce intentionally copied the Hellenistic phalanx to create their schiltron ("hedgehog") formation. However, long spears might have been used by Picts and others in Scotland's early Middle Ages. Before 1066, long spear tactics (also found in North Wales) might have been part of informal warfare in Britain. The Scots used imported French pikes and dynamic tactics at the Battle of Flodden. However, at Flodden, the Scots faced effective light artillery and advanced over bad ground. This combination broke up the Scottish phalanxes. It allowed effective attacks by English longbowmen and soldiers with shorter, handier polearms called bills. Some old writings say that the bills cut off the heads of Scottish pikes.

The pike was briefly considered again as a weapon by European armies in the late 1700s and early 1800s. It could protect riflemen, whose slower firing rate made them vulnerable. A folding pike was invented but never given to soldiers. The Confederate Army thought about using these weapons during the American Civil War. Some were even made but probably never used in battle. Pikes were also made during World War II for the British "Croft's Pikes".

Even though it's no longer used in war, the phalanx remains a symbol of warriors moving forward as a single, united group. This idea inspired several political movements in the 20th century, especially the Spanish Falange and its ideas of Falangism.

See also

In Spanish: Falange para niños

In Spanish: Falange para niños

- Comparable formations

- Hoplite formation in art

- Pelopidas

- Point d'appui

- Roman infantry tactics

- Roman Legion

- Sarissa

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |