Epaminondas facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Epaminondas

|

|

|---|---|

|

Ἐπαμεινώνδας

|

|

Stater of the Boeotian League minted c. 364 - 362 BC by Epaminondas, whose name EΠ-AMI is inscribed on the reverse

|

|

| Personal details | |

| Born | c. 410s BC Thebes, Boeotia |

| Died | 362 BC Near Mantineia, Peloponnese |

| Military service | |

| Rank | Boeotarch |

Epaminondas (/ɪˌpæmɪˈnɒndəs/; Greek: Ἐπαμεινώνδας; born around 419–411 BC, died 362 BC) was an amazing Greek general and leader from Thebes. He lived in the 4th century BC. Epaminondas changed the ancient Greek city-state of Thebes. He helped it break free from Sparta and become very powerful in Greece. This period was known as the Theban Hegemony.

He famously defeated Sparta's army at the Battle of Leuctra. This victory weakened Sparta's power. He also freed the Messenian helots, who were Greeks enslaved by Sparta for about 230 years. Epaminondas changed the map of Greece. He broke old alliances and created new ones. He even helped build new cities. He was also a very smart military leader. He invented and used new battle strategies.

The historian Xenophon admired Epaminondas. He wrote about Epaminondas's military skills in his book Hellenica. Later, the Roman speaker Cicero called him "the first man of Greece." Even in modern times, the writer Montaigne thought he was one of the three "worthiest and most excellent men" ever. The changes Epaminondas made did not last long after his death. The power struggles between Greek city-states continued. Just 27 years after he died, Alexander the Great destroyed Thebes. Today, Epaminondas is mostly remembered for his campaigns from 371 BC to 362 BC. These campaigns weakened the great city-states and prepared the way for Macedon to take over Greece.

Contents

Learning About Epaminondas: Historical Sources

It's hard to find a lot of information about Epaminondas from ancient times. This is especially true compared to other famous people from his era. One big reason is that Plutarch's book about him is missing. Plutarch wrote many biographies of famous people. Epaminondas was one of them, paired with the Roman leader Scipio Africanus. But both these biographies are now lost. Plutarch wrote over 400 years after Epaminondas died. So, he was a secondary source, meaning he got his information from other older writings.

Some stories about Epaminondas can be found in Plutarch's books about Pelopidas and Agesilaus II. These men lived at the same time as Epaminondas. There is also a book about Epaminondas by the Roman writer Cornelius Nepos. This book is from the first century BC. Since Plutarch's book is lost, Nepos's book is a main source for Epaminondas's life.

The history of Greece from 411 BC to 362 BC is mainly told by Xenophon. He was a historian who lived during that time. His work, Hellenica, continues the story from Thucydides's History of the Peloponnesian War. Xenophon liked Sparta and its king, Agesilaus. He sometimes doesn't mention Epaminondas, or even his presence at the Battle of Leuctra. However, Xenophon does describe Epaminondas's last battle and death in the seventh book of Hellenica.

Epaminondas's role in the wars of the 4th century BC is also described by Diodorus Siculus. He wrote his Bibliotheca historica much later, in the 1st century BC. Diodorus is also a secondary source. But his writings are helpful for checking details found in other places.

Epaminondas's Early Life and Education

Epaminondas was born in Thebes. His family was important and believed they were related to the mythical Spartoi. We don't know his exact birth year, but it was likely between 419 and 411 BC. His father was Polymnis, and he had a brother named Caphisias. Both his parents lived to see his great victory at the Battle of Leuctra in 371 BC.

Epaminondas had an excellent education. He learned to play musical instruments like the cither and flute. He also learned to dance. At the gymnasium, a key part of Theban education, he preferred being agile over just being strong. He studied philosophy with Lysis of Tarentum. Lysis was a Pythagorean philosopher who lived in Epaminondas's father's house.

Lysis greatly influenced Epaminondas. Epaminondas became very dedicated to his teacher and followed Pythagorean philosophy. He was known for many good qualities. These included patriotism, honesty, selflessness, and modesty. He lived a simple life, almost poor, to be more independent. Ancient writers also noted his military skill and his ability to speak well. He was also known for being quiet but having a sharp wit and a good sense of humor. Epaminondas never married. Instead, he focused on building strong friendships, especially with his lifelong friend Pelopidas.

Epaminondas's Rise to Power: Political and Military Career

Epaminondas lived during a very busy time in Greek history. After winning the Peloponnesian War in 404 BC, Sparta became very aggressive. It started to upset many of its former allies. Thebes, meanwhile, had grown stronger during the war. It wanted to control other cities in Boeotia, a region northwest of Attica. This led to conflicts between Thebes and Sparta. By 395 BC, Thebes, along with Athens, Corinth, and Argos, was fighting against Sparta in the Corinthian War. This war lasted eight years and included some tough defeats for Thebes. In the end, Thebes had to stop expanding and rejoin its old alliance with Sparta.

However, in 382 BC, a Spartan commander named Phoebidas did something that changed everything. He marched through Boeotia and took advantage of problems within Thebes. He entered the city with his troops and seized the Cadmeia (the high fortress of Thebes). He forced the anti-Spartan leaders to leave the city. Epaminondas, who was linked to this group, was allowed to stay. The Spartans set up a government that followed their orders and kept soldiers in the Cadmeia to control Thebes.

Early Military Actions

Epaminondas is said to have fought with Theban soldiers who helped Sparta attack Mantineia in 385 BC. During this fight, he supposedly saved the life of Pelopidas. This event made their friendship even stronger. Some historians question if this story is entirely true.

Theban Coup: Taking Back Thebes (378 BC)

After Sparta took over Thebes, the exiled Thebans gathered in Athens. Pelopidas urged them to plan to free their city. In Thebes, Epaminondas secretly trained young men to fight the Spartans. In the winter of 379 BC, a small group of exiles, led by Pelopidas, sneaked into the city. They killed the pro-Spartan leaders. Epaminondas and Gorgidas then led a group of young men and Athenian soldiers to surround the Spartans in the Cadmeia.

The next day, Epaminondas and Gorgidas brought Pelopidas and his men before the Theban assembly. They encouraged the Thebans to fight for their freedom. The assembly cheered Pelopidas and his men as heroes. The Spartans in the Cadmeia were surrounded and attacked. Pelopidas knew they had to be driven out before a Spartan army arrived to help them. The Spartan soldiers eventually gave up. They were allowed to leave unharmed. This was a very close call. The Spartan soldiers met a Spartan relief force on their way back home.

Aftermath of the Coup (378–371 BC)

When Sparta heard about the uprising in Thebes, King Cleombrotus I led an army to stop it. But he turned back without fighting. Another army, led by Agesilaus II, was then sent to attack Thebes. However, the Thebans refused to fight the Spartan army directly. Instead, they built a trench and a fence outside Thebes. They stayed there, stopping the Spartans from reaching the city. The Spartans damaged the countryside but eventually left, leaving Thebes independent.

This victory made the Thebans very confident. They started fighting against other nearby cities too. Soon, Thebes was able to rebuild its old Boeotian confederacy. This was a new, democratic group of cities. The cities of Boeotia joined together. They had a group of seven generals, called Boeotarchs, chosen from seven areas in Boeotia. This joining of cities worked so well that people started using "Theban" and "Boeotian" to mean the same thing. This showed the new unity of the region.

Sparta tried to crush Thebes by invading Boeotia three times in the next few years. At first, the Thebans were afraid to face the Spartans head-on. But these fights gave them a lot of practice and training. They became braver and stronger from their constant struggles. Sparta was still the strongest land power in Greece. But the Boeotians had shown they were also a strong military and political force. During this time, Pelopidas, who wanted to fight Sparta aggressively, became a major leader in Thebes.

Epaminondas's role in these years is not fully clear. He certainly served in the Theban armies defending Boeotia. By 371 BC, he had become a Boeotarch. Given their close friendship and teamwork after 371 BC, it's likely Epaminondas and Pelopidas worked closely on Theban policy during this period.

Peace Conference of 371 BC

The years after the Theban coup saw many small fights between Sparta and Thebes. Athens also got involved. A weak attempt at a general peace was made in 375 BC. But fighting between Athens and Sparta started again by 373 BC. By 371 BC, Athens and Sparta were tired of war. So, a meeting was held in Sparta to try for peace again.

Epaminondas was a Boeotarch in 371 BC. He led the Boeotian group to the peace conference. Peace terms were agreed upon at the start. The Thebans likely signed the treaty for themselves only. However, the next day, Epaminondas caused a big problem with Sparta. He insisted on signing not just for Thebes, but for all the Boeotians. Agesilaus refused this change. He said that the cities of Boeotia should be independent. Epaminondas replied that if that were true, then the cities of Laconia (Sparta's region) should also be independent. Agesilaus was angry and removed the Thebans from the document. The Theban group returned home, and both sides prepared for war.

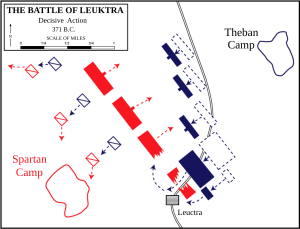

The Battle of Leuctra (371 BC)

After the peace talks failed, Sparta sent orders to King Cleombrotus. He was leading an army in Phocis. He was told to march straight to Boeotia. Cleombrotus avoided mountain passes where the Boeotians might ambush him. He entered Boeotian land from an unexpected direction. He quickly captured a fort and several ships. Then, marching towards Thebes, he camped at Leuctra. The Boeotian army came to meet him there. The Spartan army had about 10,000 foot soldiers, including 700 elite warriors called Spartiates. The Boeotians had about 6,000 soldiers. But they had better cavalry (horse soldiers) than the Spartans.

Epaminondas was put in charge of the Boeotian army. The other six Boeotarchs advised him. Pelopidas led the Sacred Band, which were the best Theban troops. Before the battle, there was a lot of talk among the Boeotarchs about whether to fight. Epaminondas always wanted to fight aggressively. With Pelopidas's help, he convinced them to go into battle. During the battle, Epaminondas showed amazing new tactics that no one had seen before in Greek warfare.

Greek armies used a formation called a phalanx formation. This formation tended to move to the right during battle. This happened because each soldier tried to protect their unarmed side with the shield of the person next to them on the right. Usually, the best troops were placed on the right side of the phalanx to stop this. So, in the Spartan phalanx at Leuctra, King Cleombrotus and the elite Spartiates were on the right. The less experienced allies were on the left.

Epaminondas used two new tactics to counter Sparta's larger army. First, he took his best troops and made them 50 ranks deep. Normal phalanxes were only 8–12 ranks deep. He placed these deep ranks on the left side, directly opposite Cleombrotus and the Spartans. Pelopidas and the Sacred Band were on the far left. Second, he knew his army couldn't match the width of the Spartan phalanx. So, he put his weaker troops on the right side. He told them to avoid fighting and slowly move back when the enemy attacked. This tactic of a deep phalanx had been used before by another Theban general, Pagondas. But Epaminondas's idea of putting the elite troops on the left and attacking in an angled line was new. He was likely the first to use the military tactic of refusing one's flank.

The battle at Leuctra began with a fight between the cavalry. The Thebans won, pushing the weaker Spartan cavalry back into their own foot soldiers. This messed up the Spartan phalanx. Then, the main battle started. The strong Theban left side attacked very quickly. The right side slowly moved back. After fierce fighting, the Spartan right side began to break under the strong attack of the Thebans. King Cleombrotus was killed. The Spartans tried to get the king's body, but their line was soon broken by the powerful Theban attack. The Spartan allies on the left side, seeing the Spartans running away, also broke and fled. The entire Spartan army retreated in chaos.

About 1,000 Spartan allies were killed. The Boeotians lost only 300 men. Most importantly, 400 of the 700 Spartiates (elite Spartan warriors) were killed. This was a huge loss for Sparta's future ability to fight wars. After the battle, the Spartans asked if they and their allies could collect their dead. Epaminondas suspected the Spartans would try to hide how many of their elite soldiers had died. So, he let the allies remove their dead first. This way, everyone could see that the remaining bodies were all Spartiates, showing how big the Theban victory was.

The victory at Leuctra completely shook Sparta's control over Greece. Sparta had always relied on its allies to create large armies. But after the defeat at Leuctra, these allies were less willing to follow Sparta's orders. Also, with so many men lost at Leuctra and other battles, Sparta was not strong enough to regain control over its former allies.

Theban Dominance: Epaminondas's Leadership

Right after Leuctra, the Thebans thought about attacking Sparta to get revenge. They also asked Athens to join them. But their allies from Thessaly convinced them not to completely destroy the remaining Spartan army. Instead, Epaminondas focused on making the Boeotian confederacy stronger. He forced the city of Orchomenus, which had been allied with Sparta, to join the league.

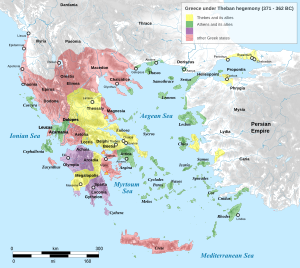

The next year, the Thebans invaded the Peloponnesus. Their goal was to break Sparta's power for good. It's not clear when Thebes decided to not just end Sparta's power, but to replace it with their own. But it's clear this became their aim. Unlike Sparta or Athens, Thebes didn't try to build a huge empire. Instead, after Leuctra, Thebes focused on making alliances in Central Greece. By late 370 BC, Thebes was secure in this area. This allowed them to expand their influence further.

First Invasion of the Peloponnese (370 BC)

When Thebes sent a messenger to Athens with news of their victory at Leuctra, Athens was silent. The Athenians then decided to take advantage of Sparta's weakness. They held a meeting in Athens. All cities (except Elis) agreed to the peace terms proposed earlier in 371 BC. This time, the treaty clearly stated that the Peloponnesian cities, once controlled by Sparta, were now independent.

Because of this, the people of Mantinea decided to combine their towns into one city and build strong walls. This made Agesilaus very angry. Also, Tegea, supported by Mantinea, started forming an Arcadian alliance. This led Sparta to declare war on Mantinea. Most Arcadian cities then joined together against Sparta. They asked Thebes for help. The Theban army arrived late in 370 BC. It was led by Epaminondas and Pelopidas, who were both Boeotarchs at this time. As they traveled into Arcadia, soldiers from many of Sparta's former allies joined them. Their army grew to about 50,000–70,000 men. In Arcadia, Epaminondas encouraged the Arcadians to form their league. He also told them to build the new city of Megalopolis as a center of power against Sparta.

Epaminondas, with Pelopidas and the Arcadians, convinced the other Boeotarchs to invade Laconia (Sparta's home region). They marched south and crossed the Evrotas River, Sparta's border. No enemy army had ever crossed it before. The Spartans did not want to fight the huge army. They just defended their city, which the Thebans did not try to capture. The Thebans and their allies destroyed the countryside of Laconia, all the way to the port of Gythium. They freed some of the Lacedaemonian perioeci (people living in Sparta's territory) from their loyalty to Sparta.

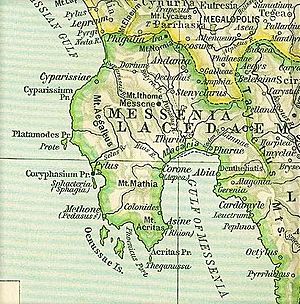

Epaminondas briefly returned to Arcadia. Then he marched south again, this time to Messenia. Sparta had conquered this region about 200 years before. Epaminondas freed the helots (enslaved people) of Messenia. He rebuilt the ancient city of Messene on Mount Ithome. Its walls were among the strongest in Greece. He then called for Messenian exiles from all over Greece to return and rebuild their homeland. Losing Messenia was very damaging to Sparta. This land made up one-third of Sparta's territory and had half of its helot population. The helots' labor had allowed the Spartans to be a "full-time" army.

Epaminondas's campaign in 370/369 BC was a brilliant strategy. It aimed to cut off Sparta's economic power. In just a few months, Epaminondas created two new states that opposed Sparta. He shook the foundations of Sparta's economy. He also greatly damaged Sparta's reputation. After achieving all this, he led his army back home, victorious.

Trial and Second Invasion (369 BC)

To finish his goals in the Peloponnesus, Epaminondas convinced his fellow Boeotarchs to stay in the field for several months after their term of office ended. When he returned home, Epaminondas faced a trial. His political enemies had arranged it. The jury laughed, the charges were dropped, and Epaminondas was re-elected as Boeotarch for the next year.

In 369 BC, the Argives, Eleans, and Arcadians wanted to continue their war against Sparta. They asked the Thebans for help again. Epaminondas, at the peak of his fame, again led an allied invasion force. When they reached the Isthmus of Corinth, the Thebans found it heavily guarded by Spartans and Athenians. Epaminondas decided to attack the weakest point, guarded by the Spartans. In a dawn attack, he broke through the Spartan position. He then joined his Peloponnesian allies. The Thebans won an easy victory and crossed the Isthmus. Diodorus said this was "a feat no whit inferior to his former mighty deeds."

However, the rest of this trip achieved little. Sicyon and Pellene became allies of Thebes. The countryside of Troezen and Epidaurus was destroyed, but the cities could not be captured. After a failed attack on Corinth and the arrival of help from Dionysius of Syracuse for Sparta, the Thebans decided to march home.

Campaign in Thessaly (368 BC)

When Epaminondas returned to Thebes, his political enemies continued to bother him. They successfully prevented him from being a Boeotarch for the year 368 BC. This was the only time between the Battle of Leuctra and his death that he was not a Boeotarch. In 368 BC, the Theban army went into Thessaly. They wanted to rescue Pelopidas and Ismenias, who had been captured by Alexander of Pherae while on a diplomatic mission. The Theban force not only failed to defeat Alexander, but they got into serious trouble when trying to retreat. Epaminondas, who was serving as a regular soldier, managed to get them out of danger. In early 367 BC, Epaminondas led a second Theban trip to free Pelopidas and Ismenias. He finally outsmarted the Thessalians and secured the release of the two Theban ambassadors without a fight.

Third Invasion of the Peloponnesus (367 BC)

In the spring of 367 BC, Epaminondas invaded the Peloponnesus again. This time, an Argive army captured part of the Isthmus at Epaminondas's request. This allowed the Theban army to enter the Peloponnesus easily. On this trip, Epaminondas marched to Achaea. He wanted them to become allies of Thebes. No army dared to challenge him in battle. The Achaean ruling families therefore agreed to ally with Thebes.

Epaminondas's decision to accept the Achaean ruling families caused protests from both the Arcadians and his political rivals. So, his agreement was quickly changed. Democracies were set up, and the ruling families were sent away. These democratic governments did not last long. The pro-Spartan nobles from all the cities banded together. They attacked each city in turn, bringing back the old ruling families. According to historian G.L. Cawkwell, "the sequel perhaps showed the good sense of Epaminondas." When these exiled nobles returned to power, they "no longer took a middle course." Because of how Thebes had treated them, they stopped being neutral. After that, they "fought zealously in support of the Lacedaemonians" (Spartans).

Growing Opposition to Thebes

In 366/365 BC, an attempt was made to create a general peace. The Persian King Artaxerxes II was asked to be the judge and guarantor. Thebes organized a meeting to get the peace terms accepted. But their diplomatic effort failed. The talks could not solve the hostility between Thebes and other states that disliked its influence. The peace was never fully accepted, and fighting soon started again. However, Thebes did gain some things from the meeting. The peace of 366/5 BC confirmed Epaminondas's policy in the Peloponnesus. Under it, the remaining members of the Peloponnesian league finally left Sparta. They recognized the independence of Messenia and the unity of Boeotia.

Throughout the decade after the Battle of Leuctra, many former allies of Thebes switched sides. They joined the Spartan alliance or even allied with other enemy states. By the middle of the next decade, even some Arcadians, whose league Epaminondas had helped create in 369 BC, had turned against Thebes. However, Epaminondas managed to break up the Peloponnesian league through diplomacy. The remaining members finally left Sparta (in 365 BC, Corinth, Epidaurus, and Phlius made peace with Thebes and Argos). Messenia remained independent and loyal to Thebes.

Boeotian armies fought across Greece as enemies appeared everywhere. Epaminondas even led his state in a challenge to Athens at sea. The Theban people voted him a fleet of one hundred ships to win over Rhodes, Chios, and Byzantium. The fleet sailed in 364 BC. But modern historians believe Epaminondas did not achieve any lasting gains for Thebes on this trip. In that same year, Pelopidas was killed while fighting against Alexander of Pherae in Thessaly. Losing Pelopidas meant Epaminondas lost his most important political ally in Thebes.

Fourth Invasion of the Peloponnesus (362 BC)

Because of the growing opposition to Theban power, Epaminondas launched his last expedition into the Peloponnese in 362 BC. The main goal was to defeat Mantinea, which had been against Theban influence. Epaminondas brought an army from Boeotia, Thessaly, and Euboea. He was joined by Tegea, Argos, Messenia, and some Arcadians. Mantinea, on the other hand, had asked for help from Sparta, Athens, Achaea, and the rest of Arcadia. So, almost all of Greece was fighting on one side or the other.

This time, just having the Theban army there was not enough to scare the enemy. Since time was running out and the Mantinean alliance showed no signs of breaking, Epaminondas decided he had to act. He heard that a large Spartan force was marching to Mantinea. He also heard that Sparta was almost undefended. So, he planned a daring night march on Sparta itself. However, the Spartan king Archidamus was warned by a messenger. Epaminondas arrived to find the city well-defended. He did attack the city, but he quickly pulled back when he realized he hadn't surprised the Spartans. Also, the Spartan and Mantinean troops who had been at Mantinea had marched to Sparta during the day. This stopped Epaminondas from attacking again.

Now, Epaminondas hoped his enemies had left Mantinea undefended in their rush to protect Sparta. He marched his troops back to his base at Tegea. Then he sent his cavalry to Mantinea. But a fight outside Mantinea's walls with Athenian cavalry ruined this plan too. Epaminondas realized that the campaign time was ending. He knew that if he left without defeating Tegea's enemies, Theban influence in the Peloponnesus would be destroyed. So, he decided to risk everything on one big battle.

What happened next on the plain in front of Mantinea was the largest battle of foot soldiers in Greek history. Epaminondas had the larger army: 30,000 foot soldiers and 3,000 cavalry. His opponents had 20,000 foot soldiers and 2,000 cavalry. Xenophon says that Epaminondas arranged his army for battle. Then he marched it in a line parallel to the Mantinean lines. It looked like his army was just marching past and wouldn't fight that day. When they reached a certain point, he had the army put down their weapons, as if they were getting ready to camp. Xenophon suggests that "by so doing he caused among most of the enemy a relaxation of their mental readiness for fighting, and likewise a relaxation of their readiness as regards their array for battle."

Then, the whole line, which had been marching from right to left past the Mantinean army, suddenly turned to face them. Epaminondas, who was at the front of the line (now the left wing), brought some companies of foot soldiers from the far right wing, from behind the battle line, to make the left wing stronger. By doing this, he recreated the powerful left wing that Thebes had used at Leuctra. This time, it was probably made up of all the Boeotians, not just the Thebans. On the sides, he placed strong forces of cavalry, supported by light-armed soldiers.

Epaminondas then gave the order to advance. This caught the enemy off guard. It caused a frantic rush in the Mantinean camp to get ready for battle. The battle went exactly as Epaminondas had planned. The cavalry on the sides pushed back the Athenian and Mantinean cavalry opposite them. Diodorus says that the Athenian cavalry, though good, could not stand against the arrows and spears from the light-armed troops Epaminondas had placed among the Theban cavalry. Meanwhile, the Theban foot soldiers advanced. Xenophon described Epaminondas's thinking: "he led forward his army prow on, like a trireme, believing that if he could strike and cut through anywhere, he would destroy the entire army of his adversaries." Like at Leuctra, the weaker right wing was told to hold back and avoid fighting. In the clash of foot soldiers, the outcome was uncertain for a moment. But then the Theban left wing broke through the Spartan line. The entire enemy phalanx was forced to flee.

However, at the height of the battle, Epaminondas was badly wounded by a Spartan. He died shortly after. After his death, Thebes and its allies did not chase the fleeing enemy. This shows how important Epaminondas was to their war effort.

Epaminondas's Death

While pushing forward with his troops at Mantinea, Epaminondas was hit in the chest by a spear. Some stories say it was a sword or a large knife. The enemy who struck him was named as Anticrates, Machaerion, or Gryllus.

The spear broke, leaving the iron tip in his body. Epaminondas fell. The Thebans around him fought hard to stop the Spartans from taking his body. When he was carried back to camp, still alive, he asked which side had won. When he was told that the Boeotians had won, he said, "It is time to die." Diodorus says that one of his friends cried and said, "You die childless, Epaminondas." Epaminondas supposedly replied, "No, by Zeus, on the contrary I leave behind two daughters, Leuctra and Mantinea, my victories." Cornelius Nepos tells a similar story, with Epaminondas's last words being, "I have lived long enough; for I die unconquered." When the spear point was removed, Epaminondas quickly passed away. As was the Greek custom, he was buried on the battlefield.

How Epaminondas is Remembered

His Character and Values

Ancient historians who wrote about Epaminondas always praised his character. They said he didn't care about money, shared what he had with friends, and refused bribes. He was one of the last followers of the Pythagorean way of life. He seemed to live a simple and strict life, even when he was the most powerful leader in Greece. Cornelius Nepos noted his honesty. He described how Epaminondas refused a bribe from a Persian ambassador. These parts of his character made him very famous after his death.

Epaminondas never married. Some people in his country criticized him for this. They believed he had a duty to have sons as great as himself to benefit the country. Epaminondas replied that his victory at Leuctra was a "daughter" destined to live forever.

His Military Skills

Books about Epaminondas all agree that he was one of the most skilled generals in Greek history. Only kings Philip II and Alexander the Great might be considered better. Even Xenophon, who didn't mention Epaminondas at Leuctra, said about his Mantinean campaign: "Now I for my part could not say that his campaign proved fortunate; yet of all possible deeds of forethought and daring the man seems to me to have left not one undone." Diodorus praised Epaminondas's military record very highly.

As a battle planner, Epaminondas was better than almost any other general in Greek history. His new strategy at Leuctra allowed him to defeat the famous Spartan phalanx with a smaller army. His decision to hold back his right flank was the first time such a tactic was recorded. Many of the new tactics Epaminondas used were also later used by Philip II. Philip spent time as a hostage in Thebes when he was young. He might have learned directly from Epaminondas.

His Lasting Impact

In some ways, Epaminondas greatly changed Greece during the 10 years he was a central figure. By the time he died, Sparta was weakened, Messenia was free, and the Peloponnese was completely reorganized. However, in another way, he left Greece much like he found it. The deep divisions and hatreds that had caused problems in Greece for over a century remained. The constant wars continued until all the Greek states were defeated by Macedon.

At Mantinea, Thebes faced the combined forces of the greatest Greek states. But the victory brought them no lasting gains. With Epaminondas gone, the Thebans went back to their usual defensive policies. Within a few years, Athens replaced them as the most powerful Greek state. No Greek state ever again forced Boeotia into the submission it had known under Spartan rule. But Theban influence quickly faded in the rest of Greece. Finally, at Chaeronea in 338 BC, the combined armies of Thebes and Athens made a desperate last stand against Philip of Macedon. They were crushed. Theban independence ended. Three years later, Thebes revolted after a false rumor that Alexander had been killed. Alexander crushed the revolt and destroyed the city. He killed or enslaved all its citizens. Just 27 years after the death of the man who had made it powerful, Thebes was wiped out. Its 1,000-year history ended in a few days.

Epaminondas is remembered as both a liberator and a destroyer. He was celebrated throughout the ancient Greek and Roman worlds as one of history's greatest men. Cicero called him "the first man, in my judgement, of Greece." Pausanias recorded a poem from his tomb:

By my counsels was Sparta shorn of her glory,

And holy Messene received at last her children.

By the arms of Thebes was Megalopolis encircled with walls,

And all Greece won independence and freedom.

Epaminondas's actions were certainly welcomed by the Messenians and others he helped against the Spartans. However, those same Spartans had been key in fighting off the Persian invasions in the 5th century BC. Their weakness was greatly felt at Chaeronea. The endless wars that Epaminondas played a central role in weakened the Greek cities. They could no longer defend themselves against their northern neighbors. As Epaminondas fought for freedom for the Boeotians and others, he brought closer the day when all of Greece would be conquered by an invader. Some historians suggest Epaminondas might have wanted a united Greece made of regional democratic groups. But even if this is true, such a plan was never carried out. Thebes's great legacy to Greece was federalism. This was a way to achieve unity without force, using a system where people were represented.

Despite all his good qualities, Epaminondas could not change the Greek city-state system. This system had constant rivalry and warfare. So, he left Greece more damaged by war but no less divided than he found it. Historians say that Epaminondas's political failure was clear even before the Battle of Mantinea. His Peloponnesian allies fought to reject Sparta, not because they truly liked Thebes. On the other hand, some conclude that Epaminondas did the best a Theban could have done. He established the power of Boeotia and ended Sparta's control over the Peloponnese.

Images for kids

-

Stater of the Boeotian League minted c. 364 - 362 BC by Epaminondas, whose name EΠ-AMI is inscribed on the reverse

-

Epaminondas defending Pelopidas at the siege of Mantinea (385 BC)

-

Messenia in the classical period

-

Isaak Walraven, The Death of Epaminondas (1726), Rijksmuseum Amsterdam

-

Epaminondas, an idealized figure in the grounds of Stowe House

See also

In Spanish: Epaminondas para niños

In Spanish: Epaminondas para niños

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |