Plutarch facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Plutarch

|

|

|---|---|

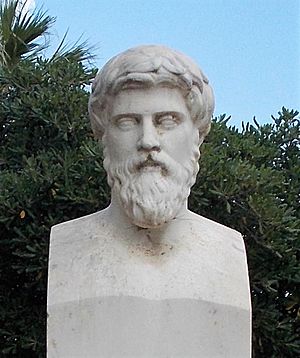

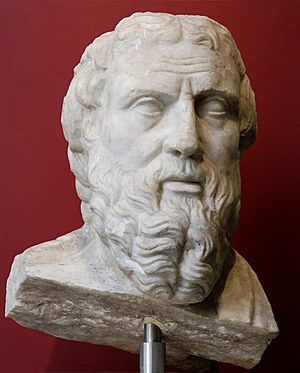

Modern portrait at Chaeronea, based on a bust from Delphi tentatively identified as Plutarch.

|

|

| Born | c. AD 46 Chaeronea, Boeotia

|

| Died | after AD 119 (aged 73–74) Delphi, Phocis

|

|

Notable work

|

Parallel Lives Moralia |

| Era | Hellenistic philosophy |

| Region | Ancient philosophy |

| School | Middle Platonism |

|

Main interests

|

Epistemology, Ethics, History, Metaphysics |

|

Influences

|

|

|

Influenced

|

|

Plutarch (born around AD 46 – died after AD 119) was a famous Greek writer and philosopher. He was also a priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. Plutarch is best known for two major works: Parallel Lives, which are biographies of famous Greeks and Romans, and Moralia, a collection of essays. When he became a Roman citizen, he was likely named Lucius Mestrius Plutarchus.

Contents

Plutarch's Life Story

Growing Up in Ancient Greece

Plutarch was born into an important family in Chaeronea, a small town in the Greek region of Boeotia. This town was about 30 kilometers east of Delphi. His father was named Autobulus, and his grandfather was Lamprias.

Plutarch's name comes from Greek words meaning "wealthy" and "leader." So, his full name meant something like "prosperous leader."

His brothers, Timon and Lamprias, are often mentioned in his writings. He spoke of Timon with great affection. Plutarch's wife was named Timoxena. He wrote a letter to her, asking her not to be too sad when their two-year-old daughter, also named Timoxena, passed away. In this letter, he hinted at believing in reincarnation.

Plutarch studied mathematics and philosophy in Athens from AD 66 to 67. He also attended the games in Delphi, where the Roman emperor Nero competed. He might have met important Romans there, including Vespasian, who would later become emperor.

Plutarch and Timoxena had at least four sons and one daughter. Sadly, two of their children died when they were young. The loss of his daughter and a young son, Chaeron, is mentioned in his letter to Timoxena. Two sons, Autoboulos and Plutarch, appear in some of his works. His book on Plato's Timaeus is dedicated to them.

Becoming a Roman Citizen

At some point, Plutarch became a Roman citizen. His sponsor was Lucius Mestrius Florus, a friend of Emperor Vespasian. This is why Plutarch took the new name Lucius Mestrius Plutarchus. As a Roman citizen, he belonged to the equestrian class, which was a group of wealthy Roman citizens. He visited Rome around AD 70 with Florus.

Plutarch was friends with several Roman nobles. He lived most of his life in Chaeronea. He was also involved in the mysteries of the Greek god Apollo. He likely took part in the Eleusinian Mysteries, which were secret religious rites.

Work as a Leader and Representative

Besides his duties as a priest, Plutarch also served as a magistrate in Chaeronea. This meant he helped manage his hometown. He also represented Chaeronea on different trips to other countries when he was younger. He held the position of archon in his town, probably for a year at a time, and likely served more than once.

Plutarch was also a manager for the Amphictyonic League for at least five terms, from 107 to 127 AD. In this role, he helped organize the Pythian Games, which were like the Olympic Games but held in Delphi.

Later Life as a Priest in Delphi

Around AD 95, Plutarch became one of the two priests for the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. The temple had become less important since ancient Greek times, but it saw a lot of new building projects around the 90s AD.

His work as a priest influenced some of his writings. One important work is "Why Pythia does not give oracles in verse." The Pythia was the priestess who gave prophecies at Delphi. Another important work is "On the 'E' at Delphi." This dialogue talks about the letter 'E' written on the temple.

According to one idea in the dialogue, the letter 'E' (which was also the Greek number 5) meant that only five of the Seven Sages of Greece were truly wise. The other two, Cleobulos and Periandros, were added to the list because of their political power.

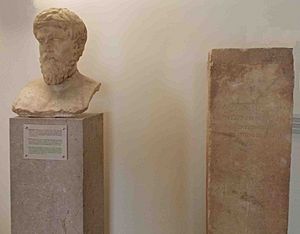

A portrait bust was made to honor Plutarch for helping to bring the Delphi shrines back to life. A statue of a philosopher at the Delphi Archaeological Museum was once thought to be Plutarch. It shows a bearded man who looks relatively young. However, a broken stone pillar next to it probably did have Plutarch's portrait. It has an inscription saying, "The Delphians, along with the Chaeroneans, dedicated this (image of) Plutarch."

Plutarch's Writings

Plutarch's surviving works were meant for Greek speakers throughout the Roman Empire.

Biographies of Roman Emperors

Plutarch's first biographies were about Roman Emperors from Augustus to Vitellius. Only the lives of Galba and Otho still exist. Parts of the lives of Tiberius and Nero are also known from other writings. These early biographies were likely published around AD 96–98.

The lives of Galba and Otho are often seen as one work. In these, Plutarch didn't just describe the people. He used their stories to show what he thought was good or bad leadership. He looked at how these emperors behaved and how their actions affected their lives.

Plutarch wrote about the tragic fates of these rulers, who fought fiercely for the throne and often destroyed each other. He noted that "The Caesars' house in Rome... received in a shorter space of time no less than four Emperors."

Parallel Lives

Plutarch's most famous work is Parallel Lives. This is a series of biographies about famous Greeks and Romans. He paired them up to show their similar good and bad qualities. It's more about understanding human nature than just a historical record.

There are 23 pairs of lives that still exist, each with one Greek and one Roman person. There are also four single lives that are not paired. Plutarch wasn't just interested in historical events. He wanted to show how a person's character affected their life. He often included interesting stories and small details, believing these showed more about a person than their biggest achievements.

He wanted to create complete pictures of these people, like a painter creates a portrait. He tried to find connections between how people looked and their moral character. Many people see him as one of the first moral philosophers.

Some of the Lives, like those of Heracles and Philip II of Macedon, are now lost. Many of the ones we have are incomplete or have been changed by later writers. The surviving Lives include those of Solon, Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, and Mark Antony.

Life of Alexander

Plutarch's Life of Alexander is paired with the Life of Julius Caesar. It is one of the main sources we have about Alexander the Great. It includes stories and events that are not found anywhere else.

Plutarch writes a lot about Alexander's strong will and desire for greatness. He tries to see how much of this was clear when Alexander was young. He also used the work of Lysippus, Alexander's favorite sculptor, to give a detailed description of Alexander's appearance.

Plutarch admired Alexander's self-control and dislike for luxury. He wrote, "He desired not pleasure or wealth, but only excellence and glory." However, as the story goes on, Alexander's actions become less admirable, like when he killed Cleitus the Black, which Alexander immediately regretted.

Life of Caesar

The Life of Caesar is a main source for understanding Julius Caesar's achievements. Plutarch starts by describing Caesar's boldness and his refusal to leave Cinna's daughter, Cornelia. Other important parts describe his military actions, battles, and how he inspired his soldiers.

Plutarch sometimes quotes directly from Caesar's own writings, like de Bello Gallico. He even mentions times when Caesar was dictating his works.

In the last part of this life, Plutarch describes the details of Caesar's assassination. He also tells what happened to the murderers, including a detailed story of a phantom appearing to Brutus at night.

Life of Pyrrhus

Plutarch's Life of Pyrrhus is very important. It is the main historical account for Roman history between 293 and 264 BCE. Other texts from this period, like those by Dionysius and Livy, are now lost.

Moralia (Essays)

The rest of Plutarch's surviving works are called the Moralia, which means "Customs and Mores." It's a varied collection of 78 essays and speeches. These include "On Fraternal Affection," about how siblings should honor and care for each other.

Another essay is "On the Worship of Isis and Osiris," which is a key source about Egyptian religious practices. There are also more philosophical essays like "On the Decline of the Oracles" and "On Peace of Mind." Some are lighter, like "Odysseus and Gryllus," a funny story between Homer's Odysseus and one of Circe's enchanted pigs. The Moralia was written before the Lives.

Spartan Stories and Sayings

The Spartans didn't write much history themselves before the Hellenistic period. So, Plutarch's five Spartan lives and his collections "Sayings of Spartans" and "Sayings of Spartan Women" are very important. They are based on sources that are now lost.

However, these writings are also debated. Plutarch lived centuries after the Sparta he wrote about. Even though he visited Sparta, many of the old customs he described had already changed. So, he didn't see everything he wrote about.

Historians note that Plutarch admired Spartan society. This might have led him to make it seem more perfect than it was. For example, the idea of Spartans being completely equal or immune to pain might be exaggerated. Even with these issues, Plutarch is still a crucial source for information on Spartan life. His writings have greatly shaped how people view Sparta.

Questions

Book IV of the Moralia contains the Roman and Greek Questions. These are short essays that explain the customs of Romans and Greeks. They ask questions like "Why were patricians not allowed to live on the Capitoline?" and then suggest answers.

On the Malice of Herodotus

In On the Malice of Herodotus, Plutarch criticizes the historian Herodotus for being unfair and misrepresenting things. Some have called it the "first instance in literature of the slashing review."

Plutarch does point out some mistakes by Herodotus. However, it's also possible that Plutarch was just doing a writing exercise. He might have been playing "devil's advocate" to see what could be said against such a popular writer. Some scholars believe Plutarch was very biased in favor of the Greek cities. He thought they could do no wrong.

Other Works

- Symposiacs (Συμποσιακά); Convivium Septem Sapientium.

- Dialogue on Love (Ερωτικος); Latin name = Amatorius.

Lost Works

We know about Plutarch's lost works from references in his own writings and from other authors. Parts of his Lives and Moralia have been lost. An old list of his works, the 'Catalogue of Lamprias', lists 227 works, but only 78 have survived.

The Romans loved the Lives. Enough copies were made over time that most of them survived. However, there are hints of 12 more Lives that are now lost. Plutarch usually wrote the life of a famous Greek, then found a Roman person to compare them to, and ended with a short comparison. Today, only 19 of the parallel lives end with a comparison, though they probably all did at one time.

Many of his Lives are also missing from the list of his writings. These include those of Hercules, the first pair of Parallel Lives, Scipio Africanus and Epaminondas, and the companions to the four solo biographies. Even the lives of important figures like Augustus, Claudius, and Nero have not been found and may be lost forever.

Lost works from the Moralia include "Whether One Who Suspends Judgment on Everything Is Condemned to Inaction."

Plutarch's Philosophy

Plutarch was a follower of Plato (a Platonist). He was also open to ideas from other schools of thought, like the Peripatetics (followers of Aristotle) and even Stoicism, even though he criticized some of their ideas. He completely rejected only Epicureanism.

He didn't focus much on difficult theoretical questions and doubted if they could ever be fully answered. He was more interested in questions about morals and religion.

Plutarch believed in a pure idea of God that fit well with Plato's ideas. He also believed in a second principle, a "Dyad," to explain the world we see. He thought this principle was an evil "world-soul" that was connected to matter from the beginning. However, in creation, it was filled with reason and organized by it. This turned it into the divine soul of the world, but it still caused all evil.

He believed God was above the world. He thought that daemons (spirits) were agents that helped God influence the world. He strongly believed in freedom of the will and the immortality of the soul.

Plutarch supported Platonic-Peripatetic ethics against the ideas of the Stoics and Epicureans. A key part of Plutarch's ethics was its strong connection to religion. He believed that God helps us through direct messages. We can understand these messages more clearly when we are in a state of "enthusiasm" and stop all other actions. This helped him explain why people believed in divination (predicting the future).

He had a similar view of popular religion. He thought the gods of different peoples were just different names for the same divine Being and the powers that serve it. He believed that myths contained philosophical truths that could be understood as allegories. So, Plutarch tried to combine philosophical and religious ideas and stay close to tradition.

Plutarch was the teacher of Favorinus.

Plutarch's Influence

Plutarch's writings had a huge impact on English and French literature. Shakespeare used parts of Thomas North's translation of the Lives in his plays. He even quoted from them directly sometimes.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau quoted Plutarch in his 1762 book Emile, or On Education. Rousseau used a passage from Plutarch to support his view against eating meat.

Ralph Waldo Emerson and the Transcendentalists were greatly influenced by the Moralia. Emerson called the Lives "a bible for heroes." He also said it was impossible to "read Plutarch without a tingling of the blood."

Montaigne's Essays used a lot from Plutarch's Moralia. Montaigne consciously copied Plutarch's easygoing style of exploring science, manners, customs, and beliefs. His Essays have over 400 references to Plutarch.

James Boswell quoted Plutarch when writing about creating "lives" instead of just biographies in his introduction to Life of Samuel Johnson. Other people who admired Plutarch included Ben Jonson, John Dryden, Alexander Hamilton, John Milton, and Francis Bacon.

Plutarch's influence decreased in the 19th and 20th centuries. However, his ideas are still part of how people think about Greek and Roman history. One of his most famous quotes was: "The world of man is best captured through the lives of the men who created history."

Translations of Lives and Moralia

Plutarch's works have been translated from the original Greek into many languages. These include Latin, English, French, German, Italian, Polish, and Hebrew.

H. J. Rose, a British classical scholar, said that for a modern reader who doesn't know Greek, Plutarch is "almost as good in a translation as in the original."

French Translations

Jacques Amyot's translations brought Plutarch's works to Western Europe. He studied the Vatican text of Plutarch and published a French translation of the Lives in 1559 and Moralia in 1572. These were widely read across Europe. Amyot's translations also had a big impact in England. Thomas North later published his English translation of the Lives in 1579, based on Amyot's French translation, not the original Greek.

English Translations

Plutarch's Lives were translated into English by Sir Thomas North in 1579, using Amyot's French version. The complete Moralia was first translated into English from the original Greek by Philemon Holland in 1603.

In 1683, John Dryden began a life of Plutarch and supervised a translation of the Lives by several people, based on the original Greek. This translation has been updated many times, most recently in the 19th century by Arthur Hugh Clough (first published in 1859).

In 1770, English brothers John and William Langhorne published "Plutarch's Lives from the original Greek."

From 1901 to 1912, an American classicist, Bernadotte Perrin, created a new translation of the Lives for the Loeb Classical Library. The Moralia is also in the Loeb series, translated by different authors.

Penguin Classics started a series of translations by various scholars in 1958.

Italian Translations

Some main Italian translations from the late 15th century include:

- Battista Alessandro Iaconelli, Vite di Plutarcho traducte de Latino in vulgare in Aquila, L’Aquila, 1482.

- Lodovico Domenichi, Vite di Plutarco. Tradotte da m. Lodouico Domenichi, con gli suoi sommarii posti dinanzi a ciascuna vita..., Venice, 1560.

- Francesco Sansovino, Le vite de gli huomini illustri greci e romani, di Plutarco Cheroneo sommo filosofo et historico, tradotte nuovamente da M. Francesco Sansovino..., Venice, 1564.

Latin Translations

There are several Latin translations of Parallel Lives. One notable one was called "Pour le Dauphin" (French for "for the Prince"), written for the court of Louis XV of France. There was also a 1470 translation by Ulrich Han.

German Translations

- Hieronymus Emser translated De capienda ex inimicis utilitate in 1519.

- The biographies were translated by Gottlob Benedict von Schirach (1743–1804) and printed in Vienna (1776–1780).

- Johann Friedrich Salomon Kaltwasser translated Plutarch's Lives and Moralia into German.

Hebrew Translations

After some Hebrew translations of parts of Plutarch's Parallel Lives in the 1920s and 1940s, a complete translation was published in three volumes by the Bialik Institute in 1954, 1971, and 1973.

Pseudo-Plutarch

Some editions of the Moralia include works that were later found to be falsely attributed to Plutarch. This means someone else wrote them, but they were thought to be by Plutarch. These include the Lives of the Ten Orators, On the Opinions of the Philosophers, On Fate, and On Music.

These works are all believed to be by one unknown author, called "Pseudo-Plutarch" (meaning "False Plutarch"). Pseudo-Plutarch lived sometime between the third and fourth centuries AD. Even though they were falsely attributed, these works are still considered important for historical information.

See also

In Spanish: Plutarco para niños

In Spanish: Plutarco para niños

- Middle Platonism

- Numenius of Apamea

- 6615 Plutarchos

- Plutarchia (wasp)

- Plutarchia (plant) (named after Plutarch)

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |