Solon facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Solon

|

|

|---|---|

| Σόλων | |

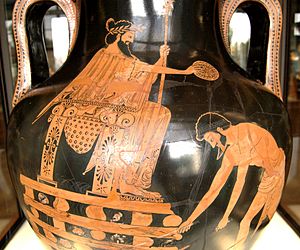

Bust of Solon, copy from a Greek original (c. 110 BC) from the Farnese Collection, now at the National Archaeological Museum, Naples

|

|

| Born | c. 630 BC |

| Died | c. 560 BC (aged approximately 70) |

| Occupation | Statesman, lawmaker, poet |

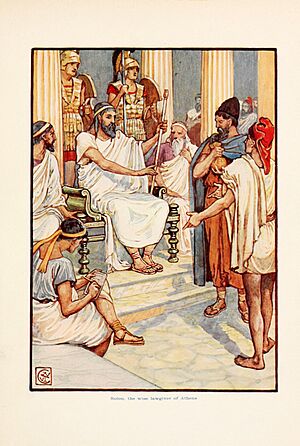

Solon (Greek: Σόλων; c. 630 – c. 560 BC) was an important leader, lawmaker, and poet in Athens, an ancient Greek city. He is famous for trying to fix problems in Athens like political fights, money troubles, and moral issues. Even though his changes didn't work perfectly at first, many people believe Solon helped create the first steps towards democracy in Athens. He also changed most of the old laws made by Draco.

We don't know everything about Solon today. His writings only exist in small pieces. Also, later writers like Herodotus and Plutarch wrote about him long after he lived. This means some details might not be exactly right. Solon wrote poems for fun, to show his love for Athens, and to explain his new laws.

Contents

Who Was Solon?

Solon was born in Athens around 630 BC. His family was well-known and belonged to a noble group called the Eupatrids. His father was likely Execestides. This means Solon's family line could be traced back to Codrus, the last King of Athens. Solon was also related to Pisistratus, who later became a powerful ruler. Even though he came from a noble family, Solon became involved in trade and business.

Athens and Megara were fighting over Salamis. Solon became the leader of the Athenian army. After some losses, Solon wrote a poem about the island. This poem helped make his soldiers feel brave again. With help from Pisistratus, Solon defeated the Megarians around 595 BC. The Megarians still wanted the island, so the Spartans were asked to decide. Solon presented Athens' case, and the Spartans gave Salamis to Athens.

In 594 BC, Solon was chosen as the archon, or chief leader, of Athens. Before he announced his plan to cancel all debts, some of his friends borrowed money and bought land. People thought Solon might have been involved. To show he was fair, Solon also canceled his own debts, which were quite large. His friends never paid back their loans.

After making his new laws, Solon traveled for ten years. He wanted to make sure Athenians couldn't force him to change his laws. He visited Egypt and talked with priests there. Some stories even say he heard about the lost city of Atlantis in Egypt. Then, Solon went to Cyprus. He helped a local king build a new capital city, which the king named Soloi after him.

Solon also visited Sardis, the capital of Lydia. There, he met King Croesus. Croesus thought he was the happiest man alive. Solon told him, "Don't call anyone happy until they are dead." He meant that good fortune can change quickly. Croesus didn't understand this until he lost his kingdom to the Persian king Cyrus and was about to be executed. Then, Croesus realized Solon's advice was wise.

When Solon returned to Athens, he strongly opposed Pisistratus, who wanted to become a powerful ruler. Solon even stood outside his home in full armor, telling people to fight against Pisistratus. But his efforts failed. Solon died soon after Pisistratus took control of Athens. Solon died in Cyprus at age 80. His ashes were scattered around Salamis, the island he fought for.

Solon was known as one of the Seven Sages, wise men whose sayings were written at Apollo's temple in Delphi. There's a story that Solon, even when old, wanted to learn a new song. When asked why, he said, "So that I may learn it before I die." This shows his love for learning.

Athens Before Solon's Reforms

During Solon's time, many Greek city-states had powerful rulers called tyrants. These were often rich nobles who took control. In Athens, a nobleman named Cylon tried to seize power in 632 BC, but he failed. Plutarch wrote that Athenian citizens gave Solon special powers because they believed he was wise enough to solve their problems peacefully. He became chief leader (archon) in 594/3 BC.

Athens faced many social and political problems. Historians have different ideas about what caused these problems:

- Rich vs. Poor: Many ancient writers, including Solon in his poems, describe a big conflict between the rich and the poor. The poor often became slaves to the rich if they couldn't pay their debts. Land was mostly owned by a few wealthy families. Solon was seen as a champion for the common people, trying to make things fair.

- Regional Rivalry: Some modern scholars believe that different groups in Athens, based on where they lived (hills, plains, coast), were fighting for control of the government. Athens was a large area, and farmers often lived in the countryside, not in the city. This made regional differences important.

- Family Rivalry: Other scholars think that powerful noble families (clans) were the main cause of conflict. These families had many followers, and their rivalries could affect everyone in society. The fight between rich and poor might have been a fight between these powerful families and their less powerful followers.

The story of Solon's Athens is complex, with different ideas about what really happened. As we learn more, people will keep discussing why Solon made his reforms and what his true goals were.

Solon's Important Reforms

Solon's laws were written on large wooden slabs or cylinders. These were kept in a public building called the Prytaneion. These "axones" worked like a spinning display, making the laws easy to read. Before Solon, the laws of Draco were on these slabs. Draco's laws were very harsh; only his law about murder remained after Solon's changes.

Even in Plutarch's time, parts of these wooden slabs were still visible. Today, we only know about Solon's laws from small quotes and comments in old books. The language of his laws was very old, even for people living centuries later, making them hard to understand. Modern scholars are careful about how much they trust these old sources. So, we don't know all the small details of Solon's laws.

Solon's changes generally covered three main areas: government, economy, and morality.

Changes to Government

Before Solon, Athens was run by nine archons, who were chosen each year by the Areopagus. The Areopagus was a council of former archons, made up of noble and wealthy men. This council had great power. There was an assembly of citizens (the Ekklesia), but the poorest citizens (the Thetes) were not allowed in. Nobles controlled how decisions were made.

Solon made big changes:

- He allowed all citizens, even the poorest, to join the Ekklesia (the assembly).

- He created a court called the Heliaia, where all citizens could serve as jurors. This meant ordinary people could help elect leaders and hold them accountable. This was a big step towards a true republic.

- Some ancient sources say Solon created a Council of Four Hundred. This council, made of citizens from Athens' four tribes, would prepare topics for the Ekklesia to discuss. However, many modern scholars are not sure if Solon actually created this council.

Solon also changed how people qualified for public office. He divided citizens into four groups based on their wealth. This system might have been used before for military service or taxes. The main measure of wealth was how many "medimnoi" (about 12 gallons) of grain a person produced each year.

- Pentakosiomedimnoi

* Produced 500 medimnoi or more of grain each year. * Could become generals or military governors.

- Hippeis

* Produced 300 medimnoi or more each year. * Wealthy enough to afford horses for the cavalry (like medieval knights).

- Zeugitai

* Produced 200 medimnoi or more each year. * Wealthy enough to afford armor for the infantry (like medieval yeomen).

- Thetes

* Produced less than 200 medimnoi each year. * Manual workers or sharecroppers. They served as helpers or light-armed soldiers.

Only the wealthiest groups (Pentakosiomedimnoi and possibly Hippeis) could be elected to the highest offices, like archons, and join the Areopagus. The Thetes were not allowed to hold any public office.

Historians still debate how democratic Solon's reforms truly were. Some see them as a very early form of democracy. Others think they mostly helped the wealthy, but still laid the groundwork for future democratic changes.

Changes to the Economy

Athens at this time had a simple economy. Most people lived in the countryside and grew just enough food for themselves. Trade was limited, even within Athens. It was hard to move goods over land, and Athens didn't have many merchant ships until later. The city often struggled to feed its growing population.

Solon's economic changes happened during a time when Athens was moving from a farming-based economy to one that needed more trade. Here are some of his specific economic reforms:

- Fathers were encouraged to teach their sons trades. If they didn't, sons were not legally required to support their fathers in old age.

- Foreign tradesmen were encouraged to move to Athens. They could become citizens if they brought their families.

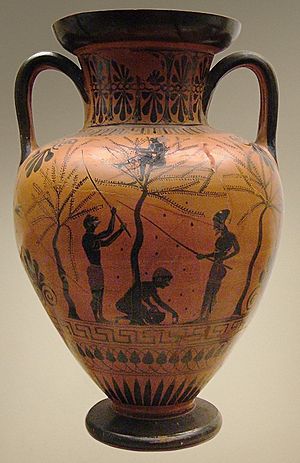

- Growing olives was encouraged. However, exporting all other fruits was forbidden.

- Solon changed weights and measures to make Athenian trade more competitive. He might have based these on successful standards from other places.

It was once thought that Solon also created Athens' first coins. However, recent studies suggest Athens didn't have its own coins until after Solon's time, around 560 BC. But people were already using silver pieces for payments.

Solon's economic reforms helped increase foreign trade. Athenian pottery, especially black-figure pottery, became very popular and was exported widely. The ban on grain export might have helped the poor. But encouraging olive production could have meant less land for growing grain, which might have made things harder for some farmers. The reasons behind Solon's economic reforms are still debated. Were they to help the poor, or to serve the needs of a changing economy?

Changes to Morality and Debt

Solon's poems show that he believed Athens was suffering because of its citizens' greed and pride. A big problem was the "horos," a stone marker on farms. This marker showed that a farmer was in debt or owed something to a rich person or a lender. Before Solon, land could not be sold. If a small farmer couldn't pay a debt, they and their family could become slaves. Sometimes, families would promise part of their farm's income or labor to a powerful family for protection. These farmers were called "hektemoroi," meaning they paid or kept one-sixth of their farm's yield. If they failed to keep their promise, they could be sold into slavery.

Solon's most famous reform was the Seisachtheia, or "shaking off of burdens." This reform aimed to fix these injustices. Its exact meaning is still debated, but it included:

- Canceling all contracts marked by the horoi.

- Forbidding people from being used as security for a loan. This ended debt slavery.

- Freeing all Athenians who had been enslaved.

Removing the horoi helped the poorest people in Attica and stopped Athenians from being enslaved by other Athenians. Solon proudly wrote that he brought back Athenians who had been sold into slavery abroad or had fled to escape it. However, some people point out that this reform might have made it harder for ordinary farmers to get loans in the future.

The Seisachtheia was part of Solon's larger plan to improve the morals of Athens. Other reforms included:

- Ending very large dowries (money or property a bride brings to a marriage).

- Laws against unfair practices in inheritance, especially for women who had no brothers and were traditionally forced to marry a close male relative to keep their father's property in the family.

- Allowing any citizen to take legal action on behalf of another citizen.

- Taking away the rights of any citizen who refused to fight in times of civil unrest or war. This was to stop people from being too lazy about politics.

Some historians believe Solon's reforms helped create a sense of civic duty and modesty among Athenians. This public spirit later helped Athenians unite against the powerful Persians.

What Happened After Solon's Reforms?

After finishing his reforms, Solon gave up his special powers and left Athens. According to Herodotus, Athens promised to follow his laws for 10 years, which matches the 10 years Solon was away. However, other ancient writers said the period was 100 years.

Within four years of Solon leaving, the old problems in Athens returned. There were issues with the new government, and some leaders refused to leave their posts. Eventually, Pisistratus, a relative of Solon, took power by force, becoming a tyrant. Plutarch says Solon blamed Athenians for being foolish and cowardly for letting this happen.

Solon's poems survive in small pieces, quoted by later writers like Plutarch. These poems are important because they give us a personal look at his reforms and ideas. Solon saw himself as someone trying to bring peace between the rich and poor in Athens.

He wrote about how some bad people are rich, and some good people are poor, but that goodness is lasting, while money changes hands.

|

πολλοὶ γὰρ πλουτεῦσι κακοί, ἀγαθοὶ δὲ πένονται: |

Some wicked men are rich, some good are poor; |

Solon also wrote that he stood like a strong shield for both sides, not letting either win unfairly.

|

ἔστην δ' ἀμφιβαλὼν κρατερὸν σάκος ἀμφοτέροισι: |

Before them both, I held my shield of might |

But his efforts were not always understood:

|

χαῦνα μὲν τότ' ἐφράσαντο, νῦν δέ μοι χολούμενοι |

Formerly they boasted of me vainly; with averted eyes |

Solon also showed strong Athenian pride, especially in the fight against Megara for Salamis. A poem he wrote about Salamis was said to have greatly inspired Athenians:

Let us go to Salamis to fight for the island

We desire, and drive away from our bitter shame!

See also

In Spanish: Solón para niños

In Spanish: Solón para niños

- Draconian constitution

- Solonia is a type of flowering plant named after Solon.