Battle of Thermopylae facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Thermopylae |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Graeco-Persian Wars | |||||||||

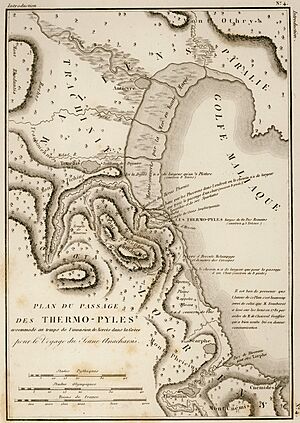

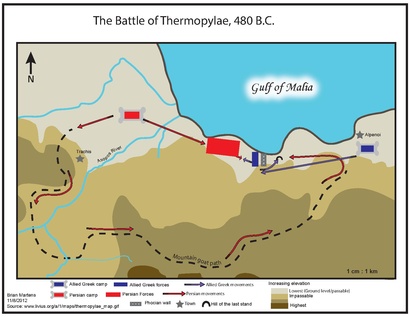

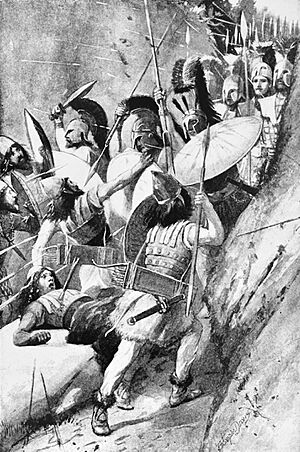

Scene of the Battle of the Thermopylae |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Greek city-states • Sparta • Thespiae • Thebes • Others |

Achaemenid Empire | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Leonidas I of Sparta † Demophilus of Thespiae † Leontiades of Thebes |

Xerxes I Mardonius Hydarnes Artapanus |

||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

| Spartan army Other Greek forces | Persian army | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 7,000 | 120,000–300,000 | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 4,000 (Herodotus) | c. 20,000 (Herodotus) | ||||||||

The Battle of Thermopylae was a famous fight in ancient Greece. It happened in 480 BC at a narrow mountain pass called Thermopylae. The powerful Persian Empire, led by King Xerxes I, fought against an alliance of Greek city-states. The city-states were led by Sparta and its brave King Leonidas I. This battle lasted for three days and became one of the most well-known events in the Greco-Persian Wars.

This battle happened at the same time as a sea battle called the Battle of Artemisium. King Xerxes of Persia wanted to conquer all of Greece. His father, Darius I, had tried before but was defeated by the Greeks at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC. Ten years later, Xerxes gathered a huge army and navy. A smart Greek leader from Athens, named Themistocles, suggested a plan. The Greeks would block the Persian army at Thermopylae. At the same time, their navy would block the Persian ships at the Straits of Artemisium.

About 7,000 Greek soldiers, including 300 brave Spartans, marched to Thermopylae. They were led by King Leonidas. The Persian army was much, much larger, with estimates from 120,000 to 300,000 soldiers. The Greeks bravely defended the pass for seven days, with three days of intense fighting. They stopped the huge Persian army from moving forward. However, a local person named Ephialtes showed the Persians a secret path around the Greek position. When Leonidas learned his army was about to be surrounded, he sent most of the Greek soldiers away. He stayed behind with his 300 Spartans, 700 Thespians, and some others, like 400 Thebans and about 900 helots. They fought until the very end, allowing the rest of the Greek army to escape safely.

When Themistocles, leading the Greek navy, heard that Thermopylae had fallen, he knew their plan was broken. The Greek navy pulled back to Salamis. The Persians then marched through Boeotia and captured Athens, which the Greeks had already emptied. But the Greek fleet then won a huge victory against the Persian navy at the Battle of Salamis in late 480 BC. King Xerxes, worried about being trapped, took most of his army and went back to Asia. Many of his soldiers suffered from hunger and sickness on the way. He left General Mardonius to continue the fight. But the next year, the Greeks completely defeated Mardonius at the Battle of Plataea, ending the Persian invasion.

People throughout history have seen the Battle of Thermopylae as a great example. It shows the strength of soldiers fighting to protect their homeland. It also teaches us how good training, proper equipment, and using the land wisely can help a smaller army against a much larger one.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

The Graeco-Persian Wars were a series of conflicts between the Greek city-states and the mighty Persian Empire. The city-states of Athens and Eretria had helped a rebellion against the Persian Empire called the Ionian Revolt (499–494 BC). King Darius I of Persia was very angry about this. He promised to punish Athens and Eretria. He also saw a chance to expand his empire into Greece.

In 492 BC, a Persian general named Mardonius secured lands near Greece. He brought Thrace back under Persian control and made Macedon a client kingdom.

In 491 BC, Darius sent messengers to all Greek city-states. He asked for "earth and water" as a sign that they would surrender to him. Most cities agreed. But in Athens, the messengers were put on trial and executed. In Sparta, they were thrown down a well! This meant Sparta was now also at war with Persia.

Darius then sent a large force in 490 BC. They attacked Naxos, took over other islands, and destroyed Eretria. Finally, they landed at Marathon to attack Athens. But the Athenian army, though outnumbered, won a stunning victory at the Battle of Marathon. This forced the Persians to retreat back to Asia.

King Darius then started to build an even bigger army to conquer Greece. But he died in 486 BC. His son, Xerxes I, became the new king. Xerxes crushed a revolt in Egypt and quickly restarted plans to invade Greece. This was not just a small attack; it was a full-scale invasion. Xerxes built bridges across the Hellespont for his army to cross into Europe. He also dug a canal through the Mount Athos peninsula. These were amazing engineering feats for that time. By early 480 BC, his huge army was ready. Many Greek cities surrendered to Xerxes, offering him earth and water.

The Athenians had also been getting ready for war. In 482 BC, a leader named Themistocles convinced them to build a powerful fleet of trireme ships. However, Athens needed help from other Greek cities to fight on land and sea. In 481 BC, Xerxes sent messengers to Greece again, but he deliberately skipped Athens and Sparta. This brought these two leading cities and their allies closer together. They formed an alliance at a meeting in Corinth in late 481 BC. This alliance allowed them to work together to defend Greece.

In spring 480 BC, the Greeks met again. They first tried to block Xerxes in a narrow valley called the Vale of Tempe. But they learned that the Persians could go around it, so they pulled back. Themistocles then suggested a new plan. They would block the Persian army at the very narrow pass of Thermopylae. At the same time, the Greek navy would block the Persian navy at the Straits of Artemisium. This two-part plan was accepted. If the Persians broke through, the cities in southern Greece planned to defend the Isthmus of Corinth. The women and children of Athens were moved to the city of Troezen for safety.

Getting Ready for Battle

The Persian army moved slowly through Thrace and Macedon. News of their approach reached Greece in August. At this time, the Spartans were celebrating a religious festival called the Carneia. During this festival, Spartan law forbade military action. Because of this, the main Spartan army could not march to war right away.

However, the Spartan leaders decided the danger was too great. They sent a smaller group of soldiers ahead. This group was led by one of their kings, Leonidas I. Leonidas took 300 of his royal bodyguards, called the Hippeis. His mission was to gather other Greek soldiers along the way and block the pass. They would wait for the main Spartan army to arrive later.

According to ancient stories, the Oracle at Delphi gave a prophecy to the Spartans. It said that either their city would be destroyed, or a king from the family of Heracles would die. Leonidas believed he was going to his death. So, he chose only Spartans who already had sons, ensuring their family lines would continue.

As Leonidas marched to Thermopylae, soldiers from other cities joined him. By the time they reached the pass, there were more than 7,000 Greek soldiers. Leonidas chose to defend the "middle gate," the narrowest part of Thermopylae. The Phocians had built a defensive wall there long ago. Leonidas also learned about a mountain path that could go around the pass. He placed 1,000 Phocians on the heights to guard this path.

In mid-August, the huge Persian army was seen approaching Thermopylae. The Greeks held a meeting. Some suggested retreating to the Isthmus of Corinth to defend southern Greece. But the Phocians and Locrians, whose homes were nearby, wanted to defend Thermopylae. Leonidas calmed everyone and agreed to stay. A famous story says that when a soldier complained that Persian arrows would block out the sun, Leonidas replied, "Won't it be nice, then, if we shall have shade in which to fight them?"

Xerxes sent a messenger to Leonidas. He offered the Greeks freedom and better land if they joined him. Leonidas refused. The messenger then demanded, "Hand over your arms!" Leonidas gave his famous reply: "Molṑn labé" (Μολὼν λαβέ), which means "Come and get them!" Xerxes waited for four days, hoping the Greeks would leave, but they did not. So, he ordered his troops to attack.

Who Fought in the Battle?

It's hard to know the exact number of soldiers in the Persian army. Ancient writers often gave very high numbers, sometimes in the millions! But modern historians think the Persian army was between 120,000 and 300,000 soldiers. King Xerxes wanted to make sure he had a huge advantage in numbers.

The Greek army was much smaller. Historians like Herodotus and Diodorus Siculus give different numbers, but here's a general idea of the forces Leonidas had:

The Greek Army

- About 300 Spartan hoplites (elite soldiers)

- Around 700 Thespians

- About 400 Thebans

- Around 1,000 Phocians

- Many other soldiers from different Greek city-states, bringing the total to about 7,000 men.

Some historians also believe there were about 900 helots (people who served the Spartans) fighting alongside them. These numbers changed during the battle, especially on the last day when many Greeks retreated.

Smart Battle Plans

The Greeks chose Thermopylae for a very smart reason. It was a narrow pass, perfect for a smaller army to defend against a much larger one. As long as they held the pass, the Persians couldn't advance into Greece. This meant the Greeks didn't need to win a huge battle; they just needed to hold their ground.

The narrow pass was ideal for the Greek fighting style. Greek soldiers, called hoplites, fought in a tight formation called a phalanx. They stood shoulder-to-shoulder with overlapping shields and long spears. This created a strong wall that was very hard for the lightly armed Persian infantry to break through. The narrow pass also protected the Greeks from being surrounded by Persian cavalry.

The main weakness for the Greeks was the mountain path that went around Thermopylae. Leonidas knew about this path and placed 1,000 Phocians there to guard it.

The Battlefield's Special Layout

In ancient times, the pass of Thermopylae was very narrow. It was a track along the shore of the Malian Gulf. Some parts were so narrow that only one chariot could pass at a time. The Phocians had even built a wall in the middle of the pass to make it stronger. The name "Hot Gates" comes from the hot springs found there.

On one side of the road was the sea, and on the other were steep, impassable hills. This made it a perfect place for King Leonidas and his men to defend. The land was rugged, with thick brush and thorny shrubs. The Persians, used to different terrain, were not prepared for this kind of fighting ground.

Today, the pass is not right next to the sea. Over many centuries, dirt and sand have built up, pushing the coastline several kilometers inland.

The Battle Days

Day One: Holding the Line

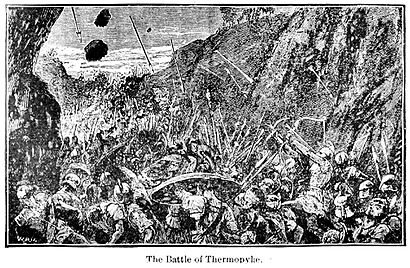

On the fifth day after the Persians arrived, King Xerxes finally ordered an attack. First, 5,000 archers shot arrows at the Greeks. But the Greek shields and helmets protected them well. The arrows were not very effective.

Then, Xerxes sent 10,000 Medes and Cissians to capture the defenders. The Persians attacked in waves, but the Greeks stood strong in front of the Phocian wall. They used their phalanx to create a wall of shields and spears. The Persians' lighter weapons could not break through. The Greeks killed so many Persians that Xerxes reportedly jumped up from his viewing seat three times in frustration. Even the elite Persian soldiers, called the Immortals, could not defeat the Greeks. The Spartans even pretended to retreat, then turned around to surprise and kill many Persians.

Day Two: A Secret Path is Revealed

On the second day, Xerxes again sent his infantry to attack. He thought the few Greek soldiers would be tired and wounded. But the Persians had no more success than on the first day. Xerxes was completely puzzled and pulled his troops back.

Later that day, something unexpected happened. A local man from Trachis, named Ephialtes, told Xerxes about a secret mountain path. This path went around the Greek position at Thermopylae. Ephialtes wanted a reward for this information. Because of his actions, the name "Ephialtes" became a word for "nightmare" and "traitor" in Greek culture.

Xerxes quickly sent his commander Hydarnes with a large force, possibly 20,000 men, to use this path. The path went along the ridge of Mount Anopaea, behind the cliffs that protected the pass.

Day Three: The Last Stand

At dawn on the third day, the Phocians guarding the mountain path heard rustling leaves. They saw the Persian column coming. The Phocians quickly retreated to a nearby hill. The Persians, not wanting to be delayed, simply shot arrows at them and continued their march to surround the main Greek force.

A runner quickly brought news to Leonidas that the path was lost. Leonidas held a meeting. Some Greeks wanted to retreat, but Leonidas decided to stay with his Spartans. He told his allies that they could leave if they wished. Many Greeks did leave, but about 2,000 soldiers chose to stay and fight. These included the 300 Spartans, 700 Thespians, 400 Thebans, and possibly the 900 helots.

Leonidas' decision to stay has been much discussed. It's believed he was following Spartan law, which forbade retreat. Some also think he was fulfilling the Oracle's prophecy, sacrificing himself to save Sparta. By staying, Leonidas and his men created a rearguard. This allowed the other 3,000 Greek soldiers to escape safely. If everyone had retreated at once, the Persian cavalry would have chased them down.

The Thespians, led by Demophilus, bravely refused to leave. They knew their city would be destroyed if the Persians won, but they chose to fight to the death. The Thebans, however, were likely forced to stay as hostages.

At dawn, Xerxes began his final attack. A force of 10,000 Persians charged the Greek formation. The Greeks fought fiercely, even moving forward into a wider part of the pass to kill as many Persians as possible. They fought with spears until they broke, then used their short swords. King Leonidas was killed by Persian archers, and a fierce fight broke out over his body. The Greeks managed to get his body back.

As the Immortals closed in, the remaining Greeks pulled back to a small hill behind the wall. The Thebans surrendered, but the rest of the Greeks fought to the very last man. They used their hands and teeth when their weapons were gone. Xerxes ordered his soldiers to surround the hill and rain down arrows until every Greek defender was dead.

The pass of Thermopylae was now open to the Persian army. The Persians lost about 20,000 soldiers, while the Greek rearguard was completely defeated, losing about 2,000 men.

What Happened After the Battle?

After the Persians left, the Greeks gathered their dead and buried them on the hill. Forty years later, King Leonidas' bones were returned to Sparta and buried with great honors. Funeral games were held every year in his memory.

With Thermopylae open, the Greek navy at Artemisium had to retreat. They sailed to the Saronic Gulf and helped move the people of Athens to Salamis.

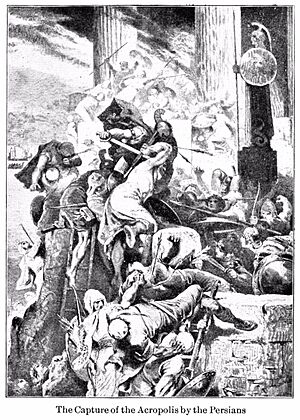

The Persian army then marched through Boeotia, burning cities like Plataea and Thespiae. They captured the empty city of Athens. Meanwhile, the Greeks, mostly from southern Greece, prepared to defend the Isthmus of Corinth. They built a wall and destroyed the road there. The Greek navy, led by Themistocles, decided to seek a big victory against the Persian fleet. They tricked the Persian navy into the narrow Straits of Salamis. In the Battle of Salamis, the Greek fleet destroyed many Persian ships, ending the threat to southern Greece.

King Xerxes, worried about his army being trapped in Europe, returned to Asia with most of his forces. Many of his soldiers died from hunger and sickness on the journey. He left General Mardonius to continue the conquest. But the next year, a Greek army decisively defeated Mardonius and his troops at the Battle of Plataea. This ended the second Persian invasion of Greece. At the same time, the Greek navy also destroyed most of the remaining Persian fleet at the Battle of Mycale.

Why Thermopylae is Remembered

Thermopylae is one of the most famous battles in ancient history. It is often mentioned in books, movies, and stories. In Western culture, the Greeks are praised for their bravery. Even though it was a defeat for the Greeks in the war, it showed that they could fight effectively against the huge Persian army. The sacrifice of Leonidas and his men boosted the morale of all Greek soldiers.

Some people call Thermopylae a "Pyrrhic victory" for the Persians. This means the winner suffered so much that it felt like a defeat. However, historians don't fully agree with this. The Persians did conquer much of Greece after Thermopylae.

The fame of Thermopylae comes from the amazing heroism of the soldiers who stayed behind. They faced certain death but refused to give up the pass. It became a symbol of free people fighting for their country and freedom. It showed how training, good equipment, and smart use of the land can help a smaller army.

Legacy

Monuments and Memories

There are several monuments at the battlefield of Thermopylae today. One is a statue of King Leonidas I, holding a spear and shield. A sign under the statue simply says: "Μολὼν λαβέ" ("Come and take them!").

The Famous Epitaph

A very famous poem, called an epitaph, was carved on a stone at the burial mound of the Spartans. It is usually credited to the poet Simonides. The original stone is gone, but a new one was made in 1955. The words from Herodotus are:

- Ὦ ξεῖν', ἀγγέλλειν Λακεδαιμονίοις ὅτι τῇδε

- κείμεθα, τοῖς κείνων ῥήμασι πειθόμενοι.

- Ō ksein', angellein Lakedaimoniois hoti tēide

- keimetha, tois keinōn rhēmasi peithomenoi.

This translates to:

- O stranger, tell the Lacedaemonians that

- we lie here, obedient to their words.

This short poem is an example of "Laconian brevity," meaning it's very short and to the point. It asks a passing stranger to deliver the sad news to Sparta that their soldiers died following their orders.

Leonidas Monument

There is a modern monument called the "Leonidas Monument" by Vassos Falireas. It has a bronze statue of Leonidas. The sign under it says "Μολὼν λαβέ" ("Come and take them!"). The carvings below show battle scenes. Two marble statues on the sides represent the Eurotas River and Mount Taygetos, important places in Sparta.

Thespian Monument

In 1997, a second monument was built for the 700 Thespians who fought alongside the Spartans. It is made of marble and has a bronze statue of the god Eros, who was very important to the ancient Thespians. A sign reads: "In memory of the seven hundred Thespians."

A plate explains the statue's meaning:

- The headless male figure shows the unknown sacrifice of the 700 Thespians.

- The outstretched chest means struggle, bravery, and strength.

- The open wing means victory, glory, spirit, and freedom.

- The broken wing means voluntary sacrifice and death.

Stories and Legends

Herodotus' account of the battle includes many colorful stories and conversations. These stories might not be fully proven, but they are a big part of the battle's legend. They often show the quick wit of the Spartans.

For example, it's said that when Leonidas was leaving for battle, his wife Gorgo asked what she should do if he didn't return. Leonidas replied, "Marry a good man and have good children."

Another story tells of a Persian scout who saw the Spartans doing exercises and combing their long hair. King Xerxes found this funny. But Demaratus, an exiled Spartan king with Xerxes, explained that Spartans prepared their hair when they were about to risk their lives. He called them "the bravest men in Greece" and warned Xerxes they would fight hard.

Herodotus also describes a Persian messenger offering Leonidas kingship over all Greece if he joined Xerxes. Leonidas answered that dying for Greece was better than ruling over his own people. When the messenger demanded their weapons, Leonidas gave his famous reply: Μολὼν λαβέ ("Come and get them!").

These brave words helped keep morale high. When a Spartan soldier named Dienekes heard that Persian arrows would be so many "as to block out the sun," he famously said, "So much the better...then we shall fight our battle in the shade."

After the battle, Xerxes asked some Greek deserters why the Greeks fought with so few men. They said that all the other men were participating in the Olympic Games. When Xerxes asked what the prize was for winning, they said "an olive-wreath." A Persian general, Tigranes, was amazed, saying, "Good heavens, Mardonius, what kind of men are these that you have pitted against us? It is not for riches that they contend but for honour!"

Commemoration

Greece has created two special coins to celebrate 2,500 years since this historic battle. The coins show the dates 2020 and 480 BC, along with the words "2,500 years since the Battle of Thermopylae."

Images for kids

-

Soldiers of the Achaemenid army of Xerxes I at the time of the Battle of Thermopylae. Tomb of Xerxes I, circa 480 BC, Naqsh-e Rustam.

Top rank: Persian, Median, Elamite, Parthian, Arian, Bactrian, Sogdian, Chorasmian, Zarangian, Sattagydian, Gandharan, Hindush (Indians), Scythian.

Bottom rank: Scythian, Babylonian, Assyrian, Arabian, Egyptian, Armenian, Cappadocian, Lydian, Ionian, Scythian, Thracian, Macedonian, Libyan, Ethiopian. -

A modern recreation of a hoplite

-

Crown-wearing Achaemenid king killing a Greek hoplite. Impression from a cylinder seal, sculpted circa 500 BC–475 BC, at the time of Xerxes I. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

-

The Persian Gates narrow pass leading to Persepolis

See also

In Spanish: Batalla de las Termópilas para niños

In Spanish: Batalla de las Termópilas para niños

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |