Greco-Persian Wars facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Greco-Persian Wars |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

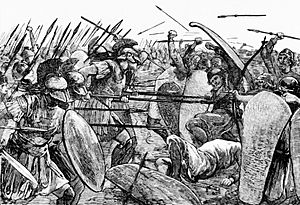

Combat between a Persian soldier (left) and a Greek hoplite (right), depicted on a kylix at the National Archaeological Museum of Athens |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Greek city-states: • Athens • Sparta • Peloponnesian League • Plataea • Thebes • Thespiae • Cyprus • Delian League |

Achaemenid Empire

Greek vassals: • Halicarnassus • Thessalia • Boeotia • Thebes • Macedon |

||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Miltiades Pericles Leonidas I † Themistocles Adeimantus Ameinias of Athens Arimnestos Dionysius the Phocaean Eurybiades Leotychides Pausanias Xanthippus Charopinos Hermophantus Melanthius † Posidonius † Stesilaos † Amompharetus † Aristagoras † Aristocyprus † Callimachus † Charitimides † Cimon † Cynaegirus † Demophilus † Eualcides † Histiaeus † Onesilus † Perilaus † Coes of Mytilene Leontiades |

Darius I Xerxes I Artaxerxes I Artemisia I Ariomardus Artabazus Artapanus Artaphernes Artaphernes (son of Artaphernes) Artyphius Datis Boges Gongylos Hippias Hydarnes II Masistes Megabates Megabazus Megabyzus Otanes Tithraustes Artayntes Azanes (son of Arteios) Hyamees Ithamitres Peraxes Artybius † Daurises † Mardontes † Tigranes † Achaemenes † Ariabignes † Damasithymus † Mardonius † Masistius † Pherendatis † Artayctes Aridolis |

||||||||

The Greco-Persian Wars were a series of big conflicts between the powerful Achaemenid Empire (also known as Persia) and the many independent Greek city-states. These wars lasted for about 50 years, from 499 BC to 449 BC. The trouble began when the Persian Empire, led by Cyrus the Great, took over the Greek cities in a region called Ionia around 547 BC. The Persians found it hard to control these freedom-loving Greek cities, so they put their own rulers, called tyrants, in charge. This setup caused a lot of problems for both the Greeks and the Persians.

In 499 BC, a Greek ruler named Aristagoras from Miletus tried to conquer the island of Naxos with Persian help. When this plan failed, Aristagoras encouraged all the Greek cities in Asia Minor to rebel against Persia. This started the Ionian Revolt, which lasted until 493 BC. The cities of Athens and Eretria sent soldiers to help the rebels. In 498 BC, these forces captured and burned Sardis, a major Persian city. The Persian king, Darius the Great, promised to get revenge on Athens and Eretria for this attack. The revolt continued, but in 494 BC, the Persians defeated the Ionian fleet at the Battle of Lade. This defeat caused the rebellion to collapse.

King Darius wanted to protect his empire from more revolts and stop the mainland Greeks from interfering. So, he planned to conquer Greece and punish Athens and Eretria. The first Persian invasion of Greece began in 492 BC. The Persian general Mardonius successfully brought Thrace and Macedon back under Persian control. However, his fleet was damaged in a storm, ending that campaign early. In 490 BC, a second Persian force sailed across the Aegean Sea. They conquered several islands and destroyed Eretria. But when they tried to attack Athens, the Athenians bravely defeated them at the Battle of Marathon. This stopped the Persian invasion for a while.

Darius then started planning a full conquest of Greece, but he passed away in 486 BC. His son, Xerxes, took over the plan. In 480 BC, Xerxes led a massive army, one of the biggest ever seen in ancient times, into Greece. The Persians won a famous battle at Battle of Thermopylae, which allowed them to burn the empty city of Athens and take over much of Greece. However, the Greek fleet surprised and defeated the Persian navy at the Battle of Salamis. The next year, the united Greek forces won another major victory against the Persian army at the Battle of Plataea. This ended the Persian invasion of Greece.

After these victories, the Greeks continued to fight back. They destroyed the rest of the Persian fleet at the Battle of Mycale. Then, they removed Persian soldiers from other areas. The Greek city-states of Ionia and Macedon regained their freedom. A new alliance, called the Delian League, was formed under Athens' leadership to continue fighting Persia. This League campaigned for another 30 years. They won a great victory at the Battle of the Eurymedon in 466 BC, securing freedom for the Ionian cities. However, a Greek effort to help a revolt in Egypt against Persia ended in disaster. After a final campaign in Cyprus in 451 BC, the Greco-Persian Wars quietly ended. Some historians believe a peace treaty, called the Peace of Callias, was signed between Athens and Persia.

Contents

- Learning About the Greco-Persian Wars

- How the Wars Began: The Story of Ionia

- Early Meetings: Persia and the Greek City-States

- The Ionian Revolt: Greeks Fight for Freedom

- Persia's First Attack on Mainland Greece

- A Break in the Fighting: Preparing for the Next Big War

- The Second Great Persian Invasion

- The Greeks Fight Back: Taking the Offensive

- The Delian League: A New Greek Alliance

- Was There a Peace Treaty? The Peace of Callias

- What Happened After the Wars?

- Images for kids

Learning About the Greco-Persian Wars

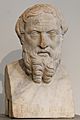

The main person who wrote about these wars was a Greek historian named Herodotus. He was born in 484 BC and wrote his famous book, The Histories, around 440–430 BC. He wanted to understand why the Greeks and Persians fought. Many people call him the "Father of History" because he tried to find out the real reasons behind events. Later historians, like Thucydides, also wrote about this time.

How the Wars Began: The Story of Ionia

Long ago, after a period called the Greek Dark Ages, many Greeks moved from mainland Greece to Asia Minor. They settled along the coast and formed cities, especially in a region called Ionia. These Ionian cities were independent but shared a common Greek culture.

Later, the powerful Lydians from western Asia Minor conquered these Ionian cities. The Lydian king, Croesus, eventually took control of all the Greek city-states in the area.

Around 550 BC, a Persian prince named Cyrus the Great started a rebellion and created the mighty Achaemenid Empire. Croesus of Lydia attacked Cyrus, but he was defeated, and Lydia fell to the Persians. This meant that the Greek cities of Ionia, which had been under Lydian rule, now became part of the vast Persian Empire. The Persians found it hard to govern these independent-minded Greek cities. To keep control, they often put local rulers, called tyrants, in charge of each city. This system often led to unhappiness among the Greek people.

How Armies Fought Back Then

In the Greco-Persian Wars, both sides used soldiers with spears and archers. Greek armies focused on heavily armored foot soldiers, while Persian armies had a mix of lighter troops.

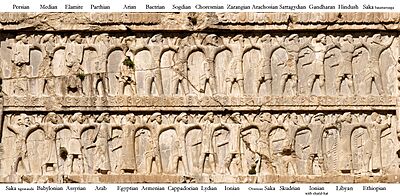

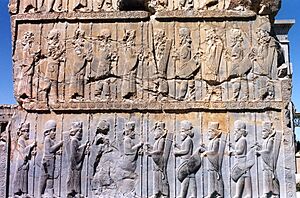

Persian Soldiers and Their Tactics

The Persian army was made up of soldiers from many different parts of their huge empire. They usually carried a bow, a short spear, and a sword or axe, along with a wicker shield. They often wore leather armor. Persians likely used their bows first to weaken the enemy, then moved in with spears and swords. Some special Persian infantry, called 'sparabara', had larger shields and longer spears to protect the archers behind them.

Greek Hoplites and Their Strengths

Greek warfare centered around the hoplite phalanx. Hoplites were foot soldiers, usually middle-class citizens who could afford their own armor. Their heavy armor included a breastplate, leg guards (greaves), a helmet, and a large round shield called an aspis. Hoplites carried long spears, much longer than Persian spears, and a sword. Their heavy armor and long spears made them very strong in hand-to-hand combat and protected them well from arrows. Lighter armed skirmishers, called psiloi, also helped the Greek armies.

Battles at Sea: Triremes and Tactics

Naval battles in this period used triremes, which were warships powered by three rows of oars. The main tactics were ramming enemy ships with a bronze ram at the front or having marines board enemy ships to fight. Skilled navies also used a maneuver called diekplous, which likely involved sailing through gaps in enemy lines to ram them from the side.

The Persian navy was mainly made up of ships and sailors from the seafaring people within their empire, like the Phoenicians and Egyptians.

Early Meetings: Persia and the Greek City-States

In 507 BC, Artaphernes, a Persian governor, received messengers from the newly democratic city of Athens. Athens was looking for Persian help against threats from Sparta. Artaphernes asked the Athenians for "Earth and Water," which was a symbol of giving up and becoming a subject of the Persian king. The Athenian messengers seemed to agree, but when they returned home, the Athenians were very upset and rejected the idea.

This event might have made the Persian rulers believe that Athens had promised to submit. So, when Athens later helped the Ionian Revolt, the Persians saw it as a broken promise and an act of rebellion.

The Ionian Revolt: Greeks Fight for Freedom

The Ionian Revolt was a series of rebellions by Greek cities in Asia Minor against Persian rule, from 499 to 493 BC. The Greeks were unhappy with the tyrants Persia had placed in charge. The revolt began when Aristagoras of Miletus, after a failed military expedition, encouraged the Ionian cities to rebel against King Darius the Great.

In 498 BC, with help from Athens and Eretria, the Ionians marched on and burned the Persian city of Sardis. However, on their way back, they were defeated by Persian troops. This was the only major attack by the Ionians. The Persians then launched a counter-attack. In 494 BC, the Persian navy defeated the Ionian fleet at the Battle of Lade, and Miletus, the heart of the revolt, was captured and its people enslaved. This ended the rebellion.

The Ionian Revolt was the first big conflict between Greece and the Persian Empire. It brought Asia Minor back under Persian control, but King Darius vowed to punish Athens and Eretria for their support of the revolt. He decided that to secure his empire, he needed to conquer all of Greece.

Persia's First Attack on Mainland Greece

After regaining control of Ionia, the Persians planned their next moves to deal with the Greek threat. This led to the first Persian invasion of Greece, which included two main campaigns.

Mardonius's Campaign: A Rough Start for Persia

The first campaign, in 492 BC, was led by Darius's son-in-law, Mardonius. He successfully brought Thrace and Macedon fully under Persian control. However, his fleet was badly damaged in a storm near Mount Athos, forcing him to end the campaign early. Mardonius himself was injured in a raid by a Thracian tribe.

The next year, King Darius sent messengers to all Greek cities, demanding their surrender. Most cities agreed, but Athens and Sparta refused and even executed the messengers. With Athens still defiant and Sparta now against him, Darius ordered another military campaign.

The Second Persian Force: Heading for Eretria

In 490 BC, generals Datis and Artaphernes led a Persian invasion force by sea. They sailed to the island of Naxos, punishing its people for their earlier resistance by burning their city and temples. The fleet then moved across the Aegean Sea, collecting hostages and soldiers from each island.

Their main target was Eretria on the island of Euboea. The Eretrians were besieged for six days. On the seventh day, some Eretrians betrayed their city, opening the gates to the Persians. The city was destroyed, and its people were enslaved, just as Darius had commanded.

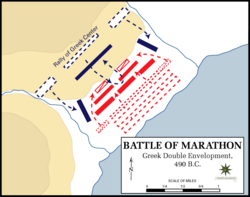

The Famous Battle of Marathon

The Persian fleet then sailed south to the bay of Marathon, about 40 kilometers from Athens. The Athenian army, led by general Miltiades, marched to block the Persians. After five days, the Persians decided to sail directly to Athens and began loading their troops, especially their strong cavalry, onto ships.

Seeing this, the 10,000 Athenian soldiers rushed down from the hills. The Greeks bravely attacked the Persian foot soldiers, defeating their wings before turning to the center of the Persian line. The remaining Persian army fled to their ships and left. Herodotus recorded that 6,400 Persian soldiers died, while only 192 Athenians were lost.

Immediately after the battle, the Athenians quickly marched back to Athens. They arrived just in time to stop Artaphernes from landing his troops there. Seeing his chance gone, Artaphernes ended the campaign and returned to Asia. The Battle of Marathon was a turning point, showing the Greeks that the mighty Persians could be defeated. It also proved how effective the heavily armored Greek hoplites could be when used wisely.

A Break in the Fighting: Preparing for the Next Big War

After the first invasion failed, Darius began to gather an even larger army to conquer Greece completely. However, in 486 BC, his subjects in Egypt revolted, delaying his plans. Darius passed away while preparing to deal with Egypt, and his son Xerxes I became the new king of Persia.

Xerxes Prepares a Massive Invasion

Xerxes crushed the Egyptian revolt and quickly restarted preparations for invading Greece. This was to be a huge invasion, requiring years of planning and gathering supplies. Xerxes decided to build bridges across the Hellespont to move his army into Europe. He also ordered a canal to be dug across the Mount Athos peninsula, where a previous Persian fleet had been destroyed by a storm. These were incredibly ambitious projects for that time.

How Big Was Xerxes's Army?

The exact number of soldiers Xerxes gathered for his second invasion is still debated by historians. Ancient writers like Herodotus claimed millions, but most modern scholars believe the numbers were much smaller, perhaps around 200,000 soldiers. The size of the Persian fleet is also debated, with estimates ranging from 600 to 1,200 warships.

Greek Cities Get Ready for War

Some Greek city-states actually supported the Persians, hoping to gain power. However, many others were determined to resist.

After the Battle of Marathon, Themistocles became a very important leader in Athens. He strongly believed that Athens needed a powerful navy to defend itself. In 483 BC, a new silver mine was discovered in Athens. Themistocles convinced the Athenians to use this silver to build a large fleet of trireme warships. He argued that these ships were needed for a long-running war with another Greek city, but his real goal was to prepare for another Persian invasion. This decision was crucial for Athens' defense.

Sparta's Role and a Secret Message

The Spartan king Demaratus had been removed from power and went to live in Persia. He became an advisor to Darius and later Xerxes on Greek matters. There's a story that before the second invasion, Demaratus sent a secret message to Sparta, warning them of Xerxes's plans by hiding it on a wax tablet.

The Greek City-States Unite

In 481 BC, Xerxes sent messengers to Greek city-states, asking for their surrender. He deliberately avoided Athens and Sparta. The cities that opposed Persia began to unite around Athens and Sparta. A meeting was held in Corinth in late 481 BC, forming an alliance of Greek city-states. This alliance, called the 'Allies', agreed to work together to defend Greece. Sparta and Athens played leading roles, but all member states helped decide defense strategies. Only about 70 of nearly 700 Greek city-states joined, which was remarkable given how often Greek cities fought each other.

The Second Great Persian Invasion

Persia Marches Through Northern Greece

After crossing into Europe in April 480 BC, the Persian army marched towards Greece. The Greek Allies first planned to defend the narrow Vale of Tempe in Thessaly. However, they learned that the Persians could bypass this pass and that Xerxes's army was too large. So, the Greeks retreated.

A new plan was suggested: defend the narrow pass of Thermopylae on land and block the nearby straits of Artemisium with their navy. This dual strategy was adopted. The Peloponnesian cities also made plans to defend the Isthmus of Corinth if needed, and the women and children of Athens were moved to safety.

Heroic Stands: Thermopylae and Artemisium

The Persian arrival at Thermopylae happened during the Olympic Games and a religious festival for the Spartans, when fighting was usually forbidden. However, the Spartans considered the threat so serious that King Leonidas I led 300 of his best soldiers, along with other Greek forces, to defend the pass. They rebuilt a wall and waited for Xerxes.

When the Persians arrived in mid-August, they waited three days for the Greeks to leave. When they didn't, Xerxes ordered an attack. The narrow pass was perfect for the Greek hoplites, who fought bravely against the much larger Persian army for two full days, even against the elite Persian Immortals. However, on the second day, a local resident named Ephialtes showed the Persians a secret mountain path that led behind the Greek lines.

When Leonidas learned they were being surrounded, he sent most of the Allied army away, staying behind with about 2,000 men to protect their retreat. On the final day, these remaining Greeks fought fiercely, killing many Persians before they were all defeated.

At the same time, a Greek naval force of 271 triremes defended the Straits of Artemisium against the Persian fleet. They held off the Persians for three days. But when they heard about the defeat at Thermopylae, and with their own fleet damaged, the Greeks retreated to the island of Salamis.

With Thermopylae lost, the path to southern Greece was open. Athens was evacuated, and its people were moved to Salamis with the help of the Greek fleet. The Peloponnesian Allies began building defenses across the Isthmus of Corinth, leaving Athens open to the Persians. Athens fell, and Xerxes ordered its destruction.

The Persians had now captured most of Greece. Xerxes wanted to finish the war quickly by destroying the Greek navy. The Greek fleet stayed near Salamis, hoping to lure the Persian fleet into battle. Thanks partly to a clever trick by Themistocles, the navies met in the narrow Straits of Salamis. Here, the huge number of Persian ships became a disadvantage, as they struggled to move and became disorganized. The Greek fleet attacked and won a decisive victory, sinking or capturing at least 200 Persian ships. This victory secured the safety of the Peloponnesus.

After this loss, Xerxes feared the Greeks might destroy his bridges across the Hellespont. His general, Mardonius, offered to stay in Greece with a chosen group of soldiers to finish the conquest, while Xerxes returned to Asia with the main army. Mardonius spent the winter in northern Greece, allowing the Athenians to return to their burned city for a short time.

Final Victories: Plataea and Mycale

Over the winter, there was tension among the Greek Allies. Athens, whose fleet was vital but whose city was unprotected, felt unfairly treated. Mardonius tried to make peace with Athens, but the Athenians refused. Athens was evacuated again, and the Persians re-occupied it. Athens, along with Megara and Plataea, asked Sparta for help, threatening to accept Persian terms if they didn't get it. In response, Sparta gathered a large army from the Peloponnese and marched to meet the Persians.

Mardonius retreated to Boeotia, near Plataea, hoping to draw the Greeks into open ground where his cavalry would be strong. The Greek army, led by the Spartan general Pausanias, stayed on high ground to protect themselves. After days of waiting, Pausanias ordered a night retreat, but it went wrong, leaving the Athenians, Spartans, and Tegeans separated. Mardonius saw his chance and attacked. However, the Persian infantry could not defeat the heavily armored Greek hoplites. The Spartans broke through and killed Mardonius. The Persian army then fled, with many trapped and killed in their camp. This was a final, decisive Greek victory.

Herodotus says that on the same afternoon as the Battle of Plataea, news of the victory reached the Greek navy near Mount Mycale in Ionia. Inspired, the Greek marines fought and won a great victory at the Battle of Mycale, destroying the rest of the Persian fleet. This crippled Persia's sea power and showed the growing strength of the Greek navy.

The Greeks Fight Back: Taking the Offensive

Ionia Rebels Again

The victory at Mycale marked a new phase where the Greeks went on the attack. The Greek cities of Asia Minor revolted against Persia once more.

Capturing Sestos: A Strategic Win

After Mycale, the Greek fleet sailed to the Hellespont to destroy the Persian bridges, but they were already gone. The Athenians stayed to attack the Chersonesos, which was still held by the Persians. They laid siege to Sestos, the strongest town. After several months, the Persians ran out of food and fled at night. The Athenians captured the city and later caught the Persian governor, Artayctes, who was executed. The Athenians took the cables from the Persian bridges as trophies and sailed home.

Brief Campaigns in Cyprus

In 478 BC, the Greek Allies sent a fleet to Cyprus and "subdued most of the island." This was likely a raid to gather treasure from Persian garrisons. The Greeks did not try to keep the island permanently, as they campaigned there again later.

Taking Byzantium and a Change in Leadership

The Greek fleet then sailed to Byzantium, which they besieged and captured. Controlling Sestos and Byzantium gave the Greeks control over the straits between Europe and Asia, and access to trade in the Black Sea.

However, the Spartan commander, Pausanias, became arrogant and difficult. He upset many of the Allied forces, especially those newly freed from Persian rule. The Ionian cities asked Athens to take over leadership of the campaign, and Athens agreed. Sparta recalled Pausanias, and although he was found innocent of working with the enemy, his reputation was damaged. This event marked a shift in leadership from Sparta to Athens.

The Delian League: A New Greek Alliance

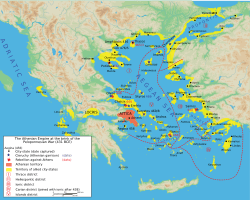

Forming the Delian League

After the events at Byzantium, Sparta seemed ready to end its involvement in the war. The Spartans felt that with mainland Greece and the Greek cities of Asia Minor freed, the war's main goal was achieved. They also thought it would be too hard to keep the Asian Greeks safe long-term. The Athenian commander, Xanthippus, strongly disagreed, saying that Athens would protect the Ionian cities, which were originally Athenian colonies. This moment showed that Athens was taking over leadership of the Greek alliance.

With Sparta stepping back, a new alliance was formed on the holy island of Delos to continue fighting Persia. This alliance, which included many Aegean islands, was officially called the 'First Athenian Alliance', but it's better known as the Delian League. Its main goals were to prepare for future invasions, get revenge on Persia, and share the spoils of war. Most member states chose to pay money to a shared treasury instead of providing soldiers or ships.

The League's Victories Against Persia

Throughout the 470s BC, the Delian League, mostly led by the Athenian politician Cimon, fought in Thrace and the Aegean Sea to remove the remaining Persian forces. In the early 460s BC, Cimon campaigned in Asia Minor to strengthen the Greek position there. At the Battle of the Eurymedon in Pamphylia, the Athenian and allied fleet won an amazing double victory, destroying a Persian fleet and then defeating their army on land. After this battle, the Persians mostly avoided direct conflict.

Later, Athens made an ambitious decision to support a revolt in Egypt against the Persian Empire. Although the Greek forces had some early successes, they were eventually defeated after a long siege. This disaster, along with ongoing wars in Greece, made Athens stop fighting Persia for a while. In 451 BC, a truce was made in Greece, and Cimon led another expedition to Cyprus. However, Cimon died during a siege, and the Athenian forces decided to withdraw, winning another double victory at the Battle of Salamis-in-Cyprus to escape. This campaign marked the end of major fighting between the Delian League and Persia, and thus the end of the Greco-Persian Wars.

Was There a Peace Treaty? The Peace of Callias

After the Battle of Salamis-in-Cyprus, the Greek historian Thucydides doesn't mention any more fighting with the Persians. However, another historian, Diodorus, claimed that a formal peace treaty, called the "Peace of Callias," was signed with the Persians. Even in ancient times, people debated whether this treaty truly existed.

Modern historians are also divided. Some believe there was indeed a peace agreement, while others think it was more of an informal understanding. If there was a treaty, its terms likely included:

- All Greek cities in Asia Minor would be self-governing.

- Persian governors and armies would not come too close to the Aegean Sea.

- No Persian warships would sail west of certain points in the Aegean.

- If Persia followed these terms, Athens would not send troops into Persian lands.

From Persia's point of view, these terms might not have been too bad. They already allowed Greek cities to govern themselves, and the limits on their navy simply recognized that the Greeks were stronger at sea. In exchange, Persia got a promise from Athens to stay out of its empire.

What Happened After the Wars?

Towards the end of the wars with Persia, the Delian League slowly changed into the Athenian Empire. Even though the fighting with Persia stopped, Athens' allies still had to pay money or provide ships. In Greece, a long-running conflict between Athens and Sparta, called the First Peloponnesian War, ended in 445 BC with a 30-year truce. However, the growing rivalry between Athens and Sparta eventually led to the devastating Peloponnesian War just 14 years later. This long war greatly weakened all of Greece.

After being defeated many times by the Greeks, Persia changed its strategy. Instead of fighting directly, Persian kings like Artaxerxes I started using a "divide-and-rule" policy. They would bribe Greek politicians to turn Athens and Sparta against each other. This kept the Greeks busy fighting among themselves and unable to threaten Persia.

There was no open war between Greeks and Persia until 396 BC. By then, the Greeks were too focused on their own conflicts. In 387 BC, Sparta even asked Persia for help. A treaty called the "King's Peace" was signed, which forced the Greek cities in Asia Minor to return to Persian rule. This was a humiliating agreement for the Greeks, undoing many of their earlier gains. It was after this treaty that Greek speakers often mentioned the "Peace of Callias" as a glorious example of a time when Greeks were free from Persian control.

Images for kids

-

Herodotus, the main historical source for this conflict

-

Thucydides continued Herodotus's narrative

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |