Ionian Revolt facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Ionian Revolt |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Greco-Persian Wars | |||||||

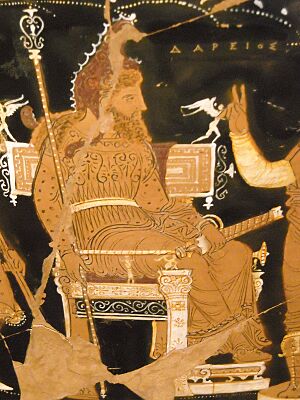

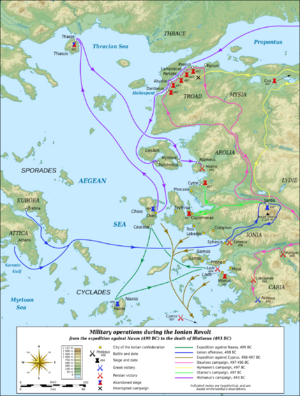

Location and main events of the Ionian Revolt. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Achaemenid Empire | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

The Ionian Revolt was a big fight where Greek cities in Asia Minor (which is modern-day Turkey) rebelled against the powerful Persian Empire. This revolt lasted from 499 BC to 493 BC. The main reason for the rebellion was that the Greek cities were unhappy with the "tyrants" (rulers) the Persians had put in charge.

Two leaders from the city of Miletus, named Histiaeus and Aristagoras, also played a big part. The Persians had taken over Ionia around 540 BC. They then let local tyrants rule, but these rulers had to answer to the Persian governor (satrap) in Sardis.

In 499 BC, Aristagoras, the tyrant of Miletus, tried to conquer Naxos with help from the Persian governor Artaphernes. This plan failed badly. Fearing he would lose his power, Aristagoras decided to start a rebellion across all of Ionia against the Persian king, Darius the Great.

In 498 BC, the Ionians, with help from Athens and Eretria, marched on Sardis. They captured and burned the city. But on their way back, Persian troops caught up to them and defeated them at the Battle of Ephesus. This was the only time the Ionians attacked. After this, they mostly defended themselves.

The Persians fought back in 497 BC, trying to take back areas that had rebelled. The revolt spread to Caria, so a large Persian army moved there. This army was ambushed and destroyed at the Battle of Pedasus. This led to a standstill in the fighting for about two years.

By 494 BC, the Persian army and navy were ready again. They headed straight for Miletus, the center of the revolt. The Ionian fleet tried to defend Miletus by sea but was badly beaten at the Battle of Lade. This happened after ships from Samos switched sides. Miletus was then surrounded, captured, and its people were taken by the Persians. This double defeat ended the revolt, and the Carians also gave up. In 493 BC, the Persians took back the remaining cities on the west coast. They then made a peace deal with Ionia that was seen as fair.

The Ionian Revolt was the first big conflict between Greece and the Persian Empire. It was the start of the Greco-Persian Wars. Even though the Persians took back Asia Minor, Darius wanted to punish Athens and Eretria for helping the revolt. He also saw that the many Greek city-states were a threat to his empire. So, Darius decided to conquer all of Greece. In 492 BC, the first Persian invasion of Greece began, directly because of the Ionian Revolt.

Contents

How the Revolt Started

In ancient times, many Greeks moved to Asia Minor and settled there. These settlers came from three main groups: the Aeolians, Dorians, and Ionians. The Ionians settled along the coasts of Lydia and Caria. They founded twelve cities that formed Ionia, like Miletus, Ephesus, and Samos.

These Ionian cities were independent but shared a common culture and meeting place. They were conquered by the Lydian king Croesus around 560 BC. Later, the rising Achaemenid Empire under Cyrus the Great conquered Lydia.

When Cyrus was fighting the Lydians, he asked the Ionians to rebel against Lydia. They refused. After Cyrus won, the Ionians offered to be his subjects, just as they had been for Croesus. Cyrus said no because they hadn't helped him before. So, the Ionians got ready to defend themselves. Cyrus sent his general Harpagus to conquer Ionia. Some cities, like Phocaea, chose to leave their homes and sail away rather than become Persian subjects. Most Ionians stayed and were conquered.

The Persians found it hard to rule the Ionians. Unlike other parts of their empire, there wasn't a clear group of leaders in Greek cities to help them. So, the Persians put a "tyrant" (ruler) in charge of each Ionian city. These tyrants often faced problems. They had to keep their own people happy enough not to rebel, while also staying in favor with the Persians.

About 40 years after Persia conquered Ionia, during the reign of King Darius the Great, the ruler of Miletus, Aristagoras, was in trouble. His uncle, Histiaeus, had been rewarded by Darius but was kept in the Persian capital, Susa, because Darius's advisors didn't trust him.

In 500 BC, some people who had been exiled from Naxos asked Aristagoras for help to take back their island. Aristagoras saw this as a chance to become more powerful in Miletus. He asked the Persian governor, Artaphernes, for an army. He promised to conquer Naxos, expand the Persian Empire, and share the profits. Artaphernes agreed and got Darius's permission. A fleet of 200 ships was prepared to attack Naxos the next year.

The Failed Attack on Naxos (499 BC)

In the spring of 499 BC, Artaphernes put his cousin Megabates in charge of the Persian forces. The ships sailed to Miletus, picked up Aristagoras's Greek troops, and headed for Naxos.

The expedition quickly went wrong. Aristagoras and Megabates argued on the way. It's said that Megabates secretly warned the Naxians. This might have been a story Aristagoras made up later to explain the failure. Either way, the Naxians were ready for a siege. The Persians surrounded Naxos for four months, but both they and Aristagoras ran out of money. The attack failed, and the fleet returned without a victory.

Starting the Ionian Revolt (499 BC)

After the Naxos failure, Aristagoras was in a very bad spot. He couldn't pay Artaphernes back and had upset the Persian royal family. He expected to be removed from power. In a desperate move to save himself, Aristagoras decided to encourage his own people, the Milesians, to rebel against the Persians. This was the start of the Ionian Revolt.

In autumn 499 BC, Aristagoras met with his supporters in Miletus. He said Miletus should revolt, and everyone agreed except for the historian Hecataeus. At the same time, a message arrived from Histiaeus, telling Aristagoras to rebel against Darius. Histiaeus likely wanted to return to Ionia himself.

So, Aristagoras openly declared his revolt. He stepped down as tyrant and announced that Miletus would be a democracy (ruled by the people). This was probably just a trick to get the Milesians excited about the rebellion. The army that had gone to Naxos was still together and included soldiers from other Greek cities. Aristagoras captured the Greek tyrants in this army and sent them back to their cities. This helped gain the support of those cities. Many tyrants were simply sent away, though one in Mytilene was killed. It's also thought that Aristagoras convinced the whole army to join his revolt and took the ships the Persians had provided. If true, this would explain why it took the Persians a long time to launch a naval attack later.

Even though the revolt started because of Aristagoras and Histiaeus, Ionia was already ready for a rebellion. The main complaint was about the tyrants the Persians had put in place. While Greek states sometimes had tyrants, this type of rule was becoming less popular. Also, the Persian-appointed tyrants didn't need the support of their people, so they could rule however they wanted. Aristagoras's actions were like throwing a match into dry wood; they sparked rebellions everywhere in Ionia. Tyrannies were removed, and democracies were set up instead.

Aristagoras had brought all of Greek Asia Minor into revolt. But he knew the Greeks would need more allies to fight the Persians successfully. In the winter of 499 BC, he first sailed to Sparta, which was the strongest Greek state in war. However, the Spartan king Cleomenes I refused to lead the Greeks against the Persians. So, Aristagoras went to Athens instead.

Athens had recently become a democracy, getting rid of its own tyrant, Hippias. Earlier, Athens had asked Persia for help against Hippias, promising to accept Persian rule. Later, Hippias tried to regain power with Spartan help, but failed and fled to Artaphernes. Hippias tried to convince Artaphernes to conquer Athens. Athens sent messengers to Artaphernes to stop him. But Artaphernes just told Athens to take Hippias back as their ruler. Athens refused and decided to be openly at war with Persia. Since they were already enemies of Persia, Athens was ready to support the Ionian cities. The fact that Ionian democracies were inspired by Athens also helped convince the Athenians to support the revolt.

Aristagoras also convinced the city of Eretria to send help. The reasons aren't fully clear. Eretria was a trading city, and Persian control of the Aegean Sea might have hurt its trade. It's also suggested that Eretria helped to repay Miletus for past support, possibly during the Lelantine War. Athens sent twenty ships (triremes) to Miletus, and Eretria sent five. The arrival of these ships was seen as the beginning of big troubles between Greeks and "barbarians" (a term Greeks used for non-Greeks).

Ionian Attack (498 BC)

During the winter, Aristagoras kept stirring up rebellion. He even told a group of Paeonians (from Thrace) who Darius had moved to Phrygia to go back home. Herodotus says he did this just to annoy the Persians.

Burning of Sardis

In the spring of 498 BC, the Athenian and Eretrian ships sailed to Ionia. They met the main Ionian force near Ephesus. Aristagoras didn't lead the army himself. He appointed his brother Charopinus and another Milesian, Hermophantus, as generals.

The Ephesians guided this army through the mountains to Sardis, which was Artaphernes's capital. The Greeks surprised the Persians and captured the lower city. However, Artaphernes still held the citadel (a strong fortress) with many soldiers. The lower city then caught fire, possibly by accident, and the fire spread quickly. The Persians in the citadel, surrounded by flames, came out and fought the Greeks in the marketplace, pushing them back. The Greeks lost heart and retreated from the city, heading back to Ephesus.

Herodotus says that when Darius heard about Sardis burning, he swore to get revenge on the Athenians. He even told a servant to remind him three times a day: "Master, remember the Athenians."

Battle of Ephesus

When other Persian forces in Asia Minor heard about the attack on Sardis, they gathered and marched to help Artaphernes. They arrived to find the Greeks had just left. So, they followed their tracks towards Ephesus. They caught up with the Greeks outside Ephesus, forcing them to turn and fight. The Persians likely had many cavalry (horseback soldiers) who could catch up quickly. Persian cavalry usually used arrows to weaken their enemies from a distance.

The tired and discouraged Greeks were no match for the Persians. They were completely defeated in the battle at Ephesus. Many were killed, including the Eretrian general, Eualcides. The Ionians who escaped fled to their own cities. The remaining Athenians and Eretrians managed to get back to their ships and sailed home to Greece.

Spread of the Revolt

Athens ended its alliance with the Ionians after this, realizing the Persians were not easy to defeat. However, the Ionians continued their rebellion. The Persians didn't immediately follow up their victory at Ephesus, probably because their temporary forces weren't ready to besiege cities. Despite the defeat, the revolt actually spread further. The Ionians sent men to the Hellespont and Propontis and captured cities like Byzantium. They also convinced the Carians to join the rebellion. Seeing the revolt spread, the kingdoms of Cyprus also rebelled against Persian rule on their own.

Persian Counter-Attack (497–495 BC)

Historians believe the events at Sardis and Ephesus happened in 498 BC. Herodotus then describes the revolt spreading, and says the Cypriots had one year of freedom, placing the Cyprus events in 497 BC. He mentions that three Persian generals, Daurises, Hymaees, and Otanes, who were married to Darius's daughters, chased the Ionians who had attacked Sardis. They defeated them and then divided the cities among themselves to conquer them. This suggests the Persian generals counter-attacked right after Ephesus. However, the cities Daurises attacked were in the Hellespont, which only joined the revolt *after* Ephesus. So, it's more likely these generals waited until the next fighting season in 497 BC to begin their counter-offensive. The Persian actions in the Hellespont and Caria seem to have happened in the same year, 497 BC.

Cyprus

In Cyprus, all kingdoms rebelled except Amathus. The leader of the Cypriot revolt was Onesilus, brother of King Gorgus of Salamis. Gorgus didn't want to rebel, so Onesilus locked him out of the city and became king. Gorgus went to the Persians. Onesilus convinced other Cypriots, except the Amathusians, to revolt. He then started to besiege Amathus.

The next year (497 BC), Onesilus heard that a Persian force led by Artybius was coming to Cyprus. Onesilus sent messengers to Ionia asking for help, and they sent a large fleet. A Persian army arrived in Cyprus, supported by a fleet from Phoenicia. The Ionians chose to fight at sea and defeated the Phoenicians. In the land battle outside Salamis, the Cypriots initially did well, even killing Artybius. However, two groups of Cypriots switched sides to the Persians. This weakened their army, and they were defeated. Onesilus and Aristocyprus, king of Soli, were both killed. The revolt in Cyprus was crushed, and the Ionians sailed home.

Hellespont and Propontis

The Persian forces in Asia Minor were reorganized in 497 BC. Three of Darius's sons-in-law, Daurises, Hymaees, and Otanes, took charge of three armies. Herodotus suggests they divided the rebellious lands and attacked their assigned areas.

Daurises, who probably had the largest army, first went to the Hellespont. He quickly captured cities like Dardanus, Abydos, and Lampsacus, supposedly in a single day each. But when he heard that the Carians were rebelling, he moved his army south to crush this new revolt. This means the Carian revolt started in early 497 BC.

Hymaees went to the Propontis and took the city of Cius. After Daurises left for Caria, Hymaees marched towards the Hellespont. He captured many Aeolian cities and some cities in the Troad region. However, he then became sick and died, ending his campaign. Meanwhile, Otanes, with Artaphernes, fought in Ionia.

Caria (496 BC)

Battle of the Marsyas River

When Daurises heard the Carians had rebelled, he led his army south into Caria. The Carians gathered at the "White Pillars" by the Marsyas River. A Cilician leader named Pixodorus suggested the Carians fight with the river behind them to prevent retreat and make them fight harder. This idea was rejected. Instead, the Carians let the Persians cross the river to fight them. The battle was long, and the Carians fought bravely but were eventually overwhelmed by the larger Persian numbers. Herodotus says 10,000 Carians and 2,000 Persians died.

Battle of Labraunda

The Carians who survived the Marsyas battle retreated to a sacred grove of Zeus at Labraunda. They debated whether to surrender or flee Asia. However, a Milesian army joined them, and with these new soldiers, they decided to keep fighting. The Persians then attacked them at Labraunda and won an even bigger victory. The Milesians suffered especially heavy losses.

Battle of Pedasus

After two victories over the Carians, Daurises began to capture the Carian strongholds. But the Carians decided to keep fighting. They set an ambush for Daurises on the road through Pedasus. Herodotus suggests this happened right after Labraunda, but some think it happened the next year (496 BC), giving the Carians time to regroup. The Persians arrived at Pedasus at night, and the ambush worked perfectly. The Persian army was wiped out, and Daurises and other Persian commanders were killed. This disaster at Pedasus created a standstill in the land war. There was little fighting in 496 BC and 495 BC.

Ionia

The third Persian army, led by Otanes and Artaphernes, attacked Ionia and Aeolia. They recaptured Clazomenae and Cyme, probably in 497 BC. But they seemed less active in 496 BC and 495 BC, likely because of the big defeat in Caria.

At the height of the Persian counter-attack, Aristagoras felt his position was hopeless. He decided to leave his role as leader of Miletus and the revolt. He left Miletus with his supporters and went to the part of Thrace that Darius had given to Histiaeus. Herodotus, who didn't think highly of Aristagoras, suggests he simply lost his courage and ran away. Some modern historians think he went to Thrace to use its natural resources to support the revolt. Others suggest he left Miletus to avoid making an internal conflict worse.

In Thrace, Aristagoras took control of Myrcinus, a city Histiaeus had founded. He started fighting the local Thracian people. However, during one campaign, probably in 497 BC or 496 BC, he was killed by the Thracians. Aristagoras was the only person who might have given the revolt a clear purpose. After his death, the revolt was left without a real leader.

Soon after, Histiaeus was released from Susa by Darius and sent to Ionia. He had convinced Darius that he could make the Ionians end their revolt. But Herodotus makes it clear that Histiaeus's real goal was to escape his almost-captivity in Persia. When he arrived in Sardis, Artaphernes directly accused him of starting the rebellion with Aristagoras, saying: "I will tell you, Histiaeus, the truth of this business: it was you who stitched this shoe, and Aristagoras who put it on." Histiaeus fled that night to Chios and eventually made his way back to Miletus. However, the Milesians had just gotten rid of one tyrant and didn't want Histiaeus back. So, he went to Mytilene in Lesbos and convinced the Lesbians to give him eight ships. He sailed to Byzantium with his followers. There, he set himself up, seizing any ships that tried to sail through the Bosporus unless they agreed to serve him.

End of the Revolt (494–493 BC)

Battle of Lade

By the sixth year of the revolt (494 BC), the Persian forces were ready again. All available land forces were combined into one army. They were joined by a fleet from the re-conquered Cypriots, along with ships from Egypt, Cilicia, and Phoenicia. The Persians headed straight for Miletus, ignoring other strongholds. They likely wanted to crush the revolt at its main point. The Median general Datis, who knew a lot about Greek affairs, was sent to Ionia by Darius around this time. He might have been in overall command of this Persian attack.

Hearing that this large force was coming, the Ionians met at the Panionium. They decided not to fight on land and left the Milesians to defend their city walls. Instead, they chose to gather every ship they could and go to the island of Lade, off the coast of Miletus, to "fight for Miletus at sea." The Ionians were joined by islanders from Lesbos. Together, they had 353 ships (triremes).

According to Herodotus, the Persian commanders worried they couldn't defeat the Ionian fleet and therefore couldn't take Miletus. So, they sent the exiled Ionian tyrants to Lade. Each tyrant tried to convince his former citizens to switch sides to the Persians. This didn't work at first. But during the week-long wait before the battle, arguments broke out among the Ionians. These arguments led to the Samians secretly agreeing to the Persian terms, though they stayed with the other Ionians for a while.

Soon after, the Persian fleet moved to attack the Ionians, who sailed out to meet them. However, as the two sides got close, the Samians sailed away back to Samos, as they had agreed with the Persians. The Lesbians, seeing their neighbors leave the battle line, quickly fled too. This caused the rest of the Ionian line to fall apart. The Chians, with a few ships from other cities, bravely stayed and fought the Persians. They even broke the Persian line and captured many ships, but they also suffered heavy losses. Eventually, the remaining Chian ships sailed away, ending the battle.

Fall of Miletus

With the Ionian fleet defeated, the revolt was basically over. Miletus was surrounded. The Persians "mined the walls and used every device against it, until they utterly captured it." Herodotus says most of the men were killed, and the women and children were enslaved. Archeological findings partly support this, showing signs of destruction and that much of the city was abandoned after the Battle of Lade. However, some Milesians did stay or quickly returned. But the city never regained its former greatness.

Miletus was "left empty of Milesians." The Persians took the city and coastal land for themselves. They gave the rest of Miletus's territory to Carians from Pedasus. The captured Milesians were brought before Darius in Susa. He settled them at "Ampé" on the coast of the Persian Gulf.

Many Samians were shocked by what their generals did at Lade. They decided to leave before their old tyrant, Aeaces of Samos, returned to rule them. They accepted an invitation from the people of Zancle to settle on the coast of Sicily. They took with them the Milesians who had escaped the Persians. Samos itself was saved from destruction by the Persians because of the Samian defection at Lade. Most of Caria then surrendered to the Persians, though some strongholds had to be captured by force.

Histiaeus's Campaign (493 BC)

Chios

When Histiaeus heard that Miletus had fallen, he seemed to appoint himself as the leader against Persia. Leaving Byzantium with his Lesbian forces, he sailed to Chios. The Chians refused to let him in, so he attacked and destroyed the remaining Chian fleet. Weakened by two defeats at sea, the Chians then accepted Histiaeus's leadership.

Battle of Malene

Histiaeus then gathered a large force of Ionians and Aeolians and went to besiege Thasos. However, he then heard that the Persian fleet was leaving Miletus to attack the rest of Ionia. So, he quickly returned to Lesbos. To feed his army, he led groups to gather food on the mainland near Atarneus and Myus. A large Persian force under Harpagus was in the area and eventually caught one of these groups near Malene. The battle was hard-fought but ended when a successful Persian cavalry charge broke the Greek line. Histiaeus himself surrendered to the Persians, thinking he could talk Darius into forgiving him. However, he was taken to Artaphernes instead. Artaphernes knew about Histiaeus's past betrayals and had him killed.

Final Operations (493 BC)

The Persian fleet and army spent the winter in Miletus. In 493 BC, they set out to finally put out the last sparks of the revolt. They attacked and captured the islands of Chios, Lesbos, and Tenedos. On each island, they formed a "human-net" of troops and swept across the whole island to find any hiding rebels. They then moved to the mainland and captured each of the remaining Ionian cities, similarly searching for rebels. While the Ionian cities were certainly damaged, none seemed to suffer as much as Miletus. Herodotus says the Persians took the most beautiful girls for the king's harem and burned the cities' temples. While this might be partly true, Herodotus probably exaggerated the destruction. Within a few years, the cities had mostly returned to normal. They were even able to provide a large fleet for the second Persian invasion of Greece just 13 years later.

The Persian army then re-conquered the settlements on the Asian side of the Propontis. The Persian fleet sailed up the European coast of the Hellespont, taking each settlement. With all of Asia Minor now back under firm Persian rule, the revolt was finally over.

What Happened Next

After punishing the rebels, the Persians wanted to make peace. Since these regions were now Persian territory again, it didn't make sense to hurt their economies further or cause more rebellions. So, Artaphernes worked to create a good relationship with his subjects. He called representatives from each Ionian city to Sardis. He told them that from then on, instead of constantly arguing, their disputes would be settled by judges. He also measured the land of each city again and set their tribute (taxes) based on their size.

Artaphernes also saw how much the Ionians disliked tyrants. The next year, Mardonius, another son-in-law of Darius, went to Ionia and removed the tyrants, replacing them with democracies. The peace that Artaphernes set up was remembered as fair for a long time. Darius even encouraged Persian nobles in the area to join Greek religious practices, especially those for Apollo. Records show that Persian and Greek nobles started marrying each other, and their children were given Greek names. Darius's friendly policies were used as a way to influence the Greeks on the mainland. In 491 BC, when Darius sent messengers to Greece demanding they surrender, most city-states accepted, with Athens and Sparta being the main exceptions.

For the Persians, the only unfinished business by the end of 493 BC was to punish Athens and Eretria for helping the revolt. The Ionian Revolt had seriously threatened Darius's empire. The Greek states on the mainland would continue to be a threat unless dealt with. So, Darius began to plan the complete conquest of Greece, starting with Athens and Eretria.

Therefore, the first Persian invasion of Greece began the next year, 492 BC. Mardonius was sent (through Ionia) to secure the land routes to Greece and, if possible, move on to Athens and Eretria. Thrace was re-conquered after breaking free during the revolts, and Macedon was forced to become a Persian subject. However, progress stopped due to a naval disaster. A second expedition was launched in 490 BC under Datis and Artaphernes, the son of the governor Artaphernes. This force sailed across the Aegean Sea, conquering the Cyclades islands, before reaching Euboea. Eretria was besieged, captured, and destroyed. The force then moved to Attica. They landed at the Bay of Marathon and were met by an Athenian army. The Athenians defeated them in the famous Battle of Marathon, ending the first Persian attempt to conquer Greece.

Why the Revolt Was Important

The Ionian Revolt was important because it was the first part of the Greco-Persian Wars. These wars included two invasions of Greece and famous battles like Marathon, Thermopylae, and Salamis. For the Ionian cities themselves, the revolt failed, and they suffered many losses. However, except for Miletus, they recovered fairly quickly and did well under Persian rule for the next forty years. For the Persians, the revolt led them into a long conflict with the Greek states that lasted fifty years, causing them many losses.

From a military point of view, it's hard to learn too much from the Ionian Revolt, except what the Greeks and Persians might have learned about each other. The Athenians and other Greeks seemed impressed by the power of Persian cavalry. Greek armies were very careful in later campaigns when facing Persian cavalry. On the other hand, the Persians didn't seem to notice how strong the Greek hoplites (heavy infantry soldiers) were. At the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC, the Persians didn't pay much attention to the mostly hoplite army, which led to their defeat. Even though they could have recruited heavy infantry from their own lands, the Persians started the second invasion of Greece without doing so. They again faced big problems against Greek armies. It's possible that because they easily won against the Greeks at Ephesus, and against similar armies at the Marsyas River and Labraunda, the Persians simply didn't think much of the hoplite phalanx (a Greek battle formation)—which proved to be a costly mistake.

Images for kids

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |